Featured

11 Photobooks that Reimagine Queer History and Visibility

From Zanele Muholi’s radical statements of identity to the photographers envisioning trans activism and community, here are must-read titles that celebrate queer voices and stories.

Courtesy the artist

Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (2024)

In Pictures for Charis, Kelli Connell takes inspiration from the life of Charis Wilson and her collaborations with Edward Weston through the contemporary lens of a queer woman artist. Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, Wilson was Weston’s partner, model, and collaborator, working with the photographer on some of his most iconic images.

Connell focuses on Wilson and Weston’s shared legacy, traveling with her own partner, Betsy Odom, to locations in the western United States where the earlier couple made photographs together more than eighty years ago. In chasing Wilson’s ghost, Connell tells her own story, finding a new kinship with the collaborative duo as she navigates a cultural landscape that has changed, yet remains mired in the same mythologies about nature, the artist, desire, and inspiration. Bringing together photographs and writing by Connell alongside Weston’s classic figure studies and landscapes, Pictures for Charis raises vital questions about photography, gender, and portraiture in the twenty-first century.

Courtesy the artist

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (2021 Edition)

Nan Goldin’s iconic visual diary The Ballad of Sexual Dependency chronicles the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family, and lovers in the 1970s and ’80s. Goldin’s candid, visceral photographs captured a world seething with life—and challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis.

First published by Aperture in 1986, Ballad continues to exert a major influence on photography and other aesthetic realms, its status as a contemporary classic firmly established. As Goldin reflects in an updated afterword from Aperture’s 2021 edition: “I took the pictures in this book so that nostalgia could never color my past. I wanted to make a record of my life that nobody could revise.”

Courtesy the artist

Ethan James Green: Young New York (2019)

Young New York presents striking portraits of New York’s millennial scene-makers. Through his diverse cast of models, artists, nightlife icons, and queer communities, Ethan James Green redefines beauty and identity for a new generation.

Under the mentorship of the late David Armstrong, Green developed a sensitive yet confident style. For three years, he photographed his close friends and community, often in Corlears Hook Park on the Lower East Side. Reflecting the intense connections he formed with his subjects, Green’s black-and-white photographs display an inherently humanist approach—calling to mind Diane Arbus’s midcentury studies of gender nonconformists. “Green’s subjects are often in states of transition, whether the transition from youth to adulthood or a gender transition, visible in top-surgery scars or budding breasts,” writes Michael Schulman for the New Yorker. “Transitions render people vulnerable, but Green’s subjects are confidently beautiful, masters of style and attitude.”

Courtesy the artist

Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs (2017)

Throughout the late 1980s and ’90s, a radical cultural scene emerged in cities across the globe, finding expression in the galleries, nightclubs, and bedrooms of New York, London, Los Angeles, and Rome. As a young artist experimenting with different artistic mediums at the time, Lyle Ashton Harris began obsessively photographing his friends, lovers, and individuals who were, or would become, figures of influence, including Nan Goldin, Stuart Hall, bell hooks, Catherine Opie, and Marlon Riggs. Harris’s photographs offer a raw, authentic portrait of the cultural and political communities that defined an era and continue to resonate to this day.

In the 2017 volume Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs, the artist’s archive of 35 mm Ektachrome images is presented alongside personal journal entries and recollections from artistic and cultural figures. It offers a unique document of what Harris has described as “ephemeral moments and emblematic figures shot in the ’80s and ’90s, against a backdrop of seismic shifts in the art world, the emergence of multiculturalism, the second wave of AIDS activism, and incipient globalization.” Together, Harris’s photographs and journals not only sketch his personal history and journey as an artist, but also provide an intimate look into this groundbreaking period of art and culture.

Courtesy the Peter Hujar Library, LLC; Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York; and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life (2017)

Peter Hujar died of AIDS in 1987, leaving behind a complex and profound body of photographs. A leading figure in the cultural scene in downtown New York in the 1970s and ’80s, Hujar was admired for his portraits of people, animals, and landscapes.

Beginning his career in the ’50s as a commercial photographer, Hujar soon decided to abandon this field and pursue a more personal artistic practice. Most well known for his portraiture, he created iconic images of some of New York’s renowned artists and writers, including Susan Sontag, William S. Burroughs, David Wojnarowicz, and Andy Warhol. As Antonio Huertas Mejías writes in an introduction to Speed of Life: “Hujar’s black-and-white photographs, in their signature simple style, make his works at once deeply evocative and moving.”

Despite being closely associated with those who crossed into the mainstream, Hujar lived on the fringes of contemporary fame, maintaining a status of an underground legend. Now he is a revered icon of the lost downtown art scene. Peter Hujar: Speed of Life (2017) gathers photographs from his archive, alongside texts by Philip Gefter, Steve Turtell, and Joel Smith, to create a thorough history of Hujar’s life and artistic practice.

Courtesy the artist

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II (2024)

South African artist Zanele Muholi is one of the most powerful visual activists of our time. Muholi first gained recognition for their 2006 series Faces and Phases that documents the LGBTIA+ community, creating ambitiously bold portraits in an attempt to build a visual history and remedy Black queer erasure. From there, Muholi began to turn the camera inward, beginning a series of evocative self-portraits. Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, Volume II (2024), is the follow-up to Muholi’s critically acclaimed first title featuring their self-portraits.

In their evocative self-portraits, Zanele Muholi explores and expands upon notions of Blackness, and the myriad possibilities of the self. Drawing on different materials or found objects referencing their environment, a specific event or lived experience, Muholi boldly explores their own image and innate possibilities as a Black person in today’s global society, and speaks emphatically in response to contemporary and historical racisms. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified,” Muholi states in an interview from the 2018 volume. “To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.”

Courtesy the artist, DOCUMENT, Chicago; team (gallery, inc.), New York; and Vielmetter Los Angeles

Paul Mpagi Sepuya (2020)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s studio portraits challenge and deconstruct traditional portraiture through the perspective of a Black, queer gaze. Through collage, layering, fragmentation, and mirror imagery, Sepuya encourages multivalent narrative readings of each image.

In 2020, Aperture and the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis co-published the first widely released publication of Sepuya’s work, and later this year Aperture will release a second volume with the artist in Dark Room A–Z (Fall 2024). For Sepuya, photography is a tactile and communal experience. His multilayered scenes come together through collaborations in his studio with groups of friends, fellow artists, and himself. Moving away from the slick artifice of contemporary portraiture, Sepuya’s frames are filled with the human elements of picture-taking, from fingerprints and smudges to dust on mirrored surfaces. Sepuya pushes this even further by directly inviting us to look inside the studio setting—while also considering the construction of subjectivity.

Courtesy the artist

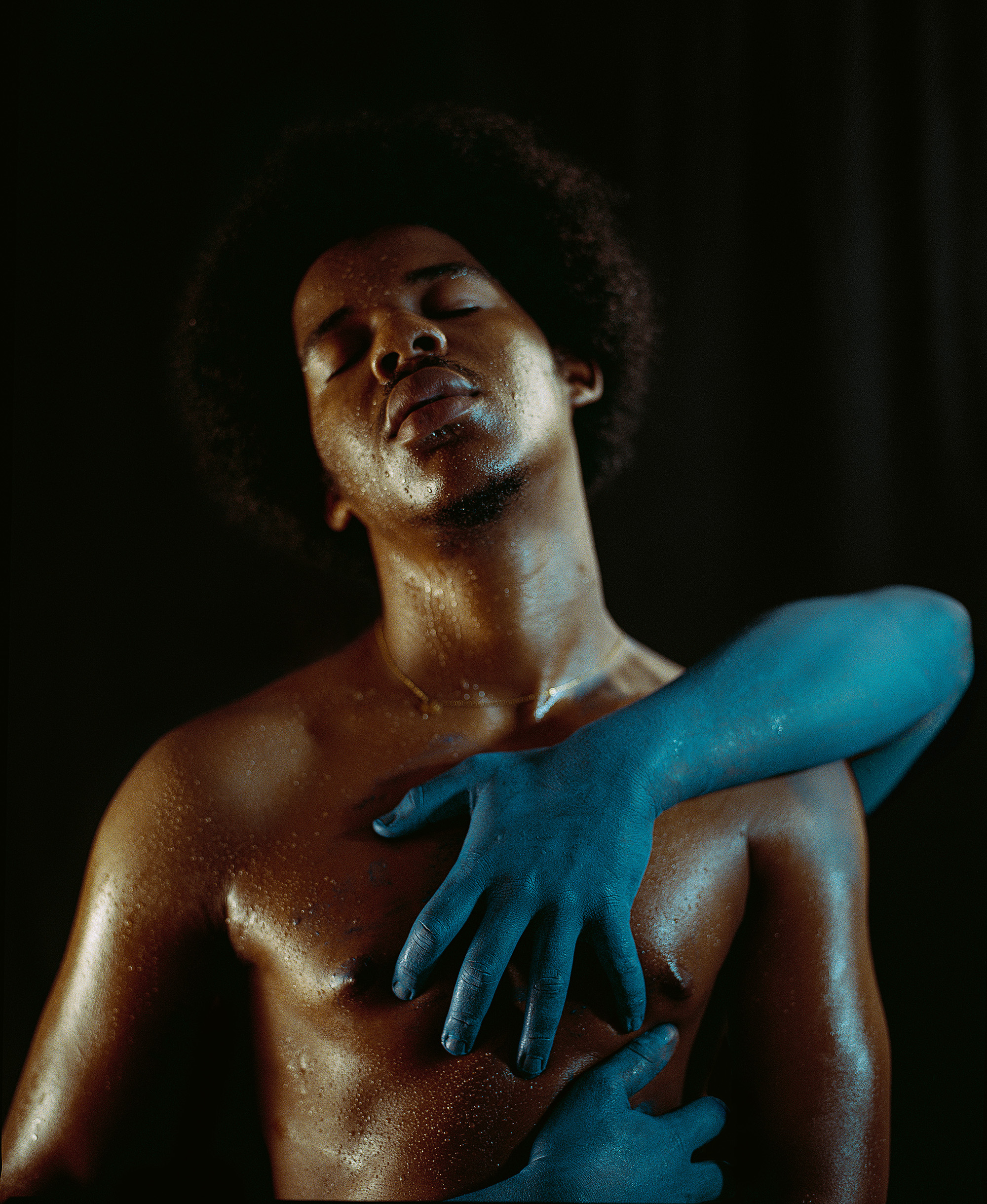

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill (2022)

A visceral and haunting exploration of Black male vulnerability, joy, and spirituality, Notes towards Becoming a Spill is the first monograph by the acclaimed multimedia artist Shikeith. Following the lyrical artistic expressions of contemporary portraitists such as Deana Lawson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Mickalene Thomas, Shikeith envisions his subjects as they inhabit various states of meditation, prayer, and ecstasy.

In work he describes as “leaning into the uncanny,” the faces and bodies of Shikeith’s subjects glisten with sweat (and tears) in a manifestation and evidence of desire. This ecstasy is what critic Antwaun Sargent proclaims as “an ideal, a warm depiction that insists on concrete possibility for another world.” Notes towards Becoming a Spill redefines the idea of sacred space and positions a queer ethic identified by its investment in vulnerability, tenderness, and joy.

Courtesy the artist

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation (2022)

In June 2020, activists Qween Jean and Joela Rivera returned to the historic Stonewall Inn—site of the 1969 riots that launched the modern gay rights movement—where they initiated weekly actions known thereafter as the Stonewall Protests. Over the following year, brought together by the urgent need to center Black trans and queer lives within the Black Lives Matter movement, thousands of people across communities and social movements gathered in solidarity, resistance, and communion.

Gathering work by twenty‑four photographers from within the movement, Revolution Is Love is the potent and celebratory visual record of a contemporary activist movement in New York City—and a moving testament to the enduring power of photography in activism, advocacy, and community. As Qween Jean reflects in an interview from the volume: “We have been at every moment of history, we’ve been at every fight, at every social-justice movement. We’ve existed.”

Courtesy the artist

Mickalene Thomas: Muse (2015)

Mickalene Thomas’s large-scale, multitextured tableaux of domestic interiors and portraits subvert the male gaze and assert new definitions of beauty. Thomas first began to photograph herself and her mother as a student at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut—which became a pivotal experience in her creative expression as an artist.

Since then, throughout her practice, Thomas’s images have functioned as personal acts of deconstruction and reappropriation. Many of her photographs draw from a wide range of cultural icons, from 1970s “Black Is Beautiful” images of women to Édouard Manet’s odalisque figures, to the mise-en-scène studio portraiture of James Van Der Zee and Malick Sidibé. Perhaps of greatest importance, however, is that Thomas’s collection of portraits and staged scenes reflect a very personal community of inspiration—a collection of muses that includes herself, her mother, her friends and lovers—emphasizing the communal and social aspects of art-making and creativity that pervade her work.

Courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

David Wojnarowicz: Brush Fires in the Social Landscape (Twentieth Anniversary Edition, 2015)

“History is made by and for particular classes of people. A camera in some hands can preserve an alternative history,” David Wojnarowicz wrote in 1991. Throughout his career, Wojnarowicz’s use of photography was extraordinary, as was his unprecedented ways of addressing the AIDS crisis, homophobia, and relentless fight against censorship. Before his death from AIDS-related complications in 1992, Aperture began collaborating with the artist on his landmark volume Brush Fires in the Social Landscape, which was published in 1994.

Brush Fires engaged with what Wojnarowicz referred to as his “tribe” or community, featuring contributions from artist and writer friends such as Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Vince Aletti, and Davide Cole (the lawyer who represented him in his case against Donald Wildmon and the American Family Association in 1990). Twenty years after its original publication, Aperture released an expanded, redesigned edition of Brush Fires, offering a new perspective on Wojnarowicz’s profound influence, courage, and legacy. “His responses were unique, thoroughly felt, and driven by an urgent necessity. In his time, his work was extraordinarily moving—it stunned,” writes Lynne Tillman in an essay from the expanded edition. “It will never be experienced again as it was then, in that very dark moment.”

See here to browse the full collection of featured titles