Featured

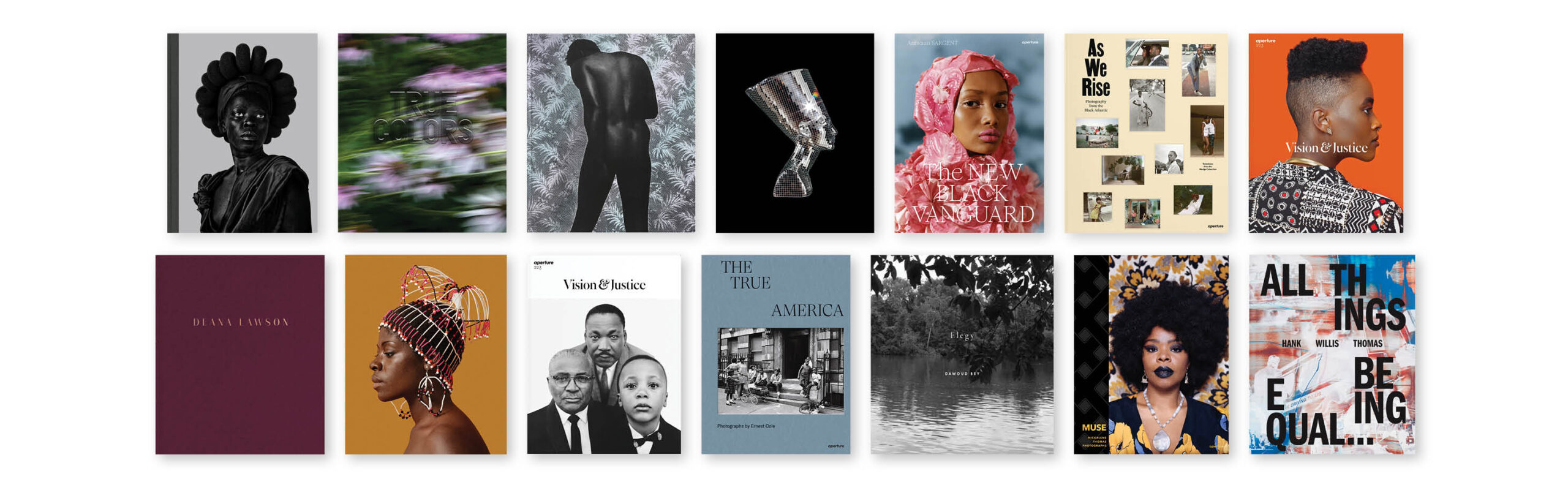

13 Photobooks that Highlight Black Lives and Artistic Visions

From monographs by Awol Erizku and Deana Lawson, to collections on fashion, community, and power, here are essential titles to read this Black History Month.

Courtesy the artist and JM.PATRAS/PARIS

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (2021)

In 1997, Dr. Kenneth Montague founded the Wedge Collection in Toronto in an effort to acquire and exhibit work by artists of African descent. As We Rise features over one hundred works from the collection, bringing together artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa in a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

From Jamel Shabazz’s definitive street portraits to Lebohang Kganye’s blurring of self, mother, and family history in South Africa, As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. As Teju Cole describes in his preface, “Too often in the larger culture, we see images of Black people in attitudes of despair, pain, or brutal isolation. As We Rise gently refuses that. It is not that people are always in an attitude of celebration—no, that would be a reverse but corresponding falsehood—but rather that they are present as human beings, credible, fully engaged in their world.”

Collect a special vinyl LP, As We Rise: Sounds from the Black Atlantic, featuring a celebratory collection of classic and contemporary Black music made throughout the Diaspora.

Courtesy the artist

Dawoud Bey: Elegy (2023)

In the artist’s most recent volume, Elegy, Dawoud Bey focuses on the landscape to create a portrait of the early African American presence in the United States. Renowned for his Harlem street scenes and expressive portraits, Bey continues his ongoing work exploring African American history. Copublished by Aperture and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Elegy focuses on three of Bey’s landscape series—Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017); In This Here Place (2021); and Stony the Road (2023)—shedding a light on the deep historical memory still embedded in the geography of the US.

Bey takes viewers to the historic Richmond Slave Trail in Virginia, where Africans were marched onto auction blocks; to the plantations of Louisiana, where they labored; and along the last stages of the Underground Railroad in Ohio, where fugitives sought self-emancipation. By interweaving these bodies of work into an elegy in three movements, Bey not only evokes history but retells it through historically grounded images that challenge viewers to go beyond seeing and imagine lived experiences. “This is ancestor work,” Bey tells the New York Times. “Stepping outside the art context, the project context, this is the work of keeping our ancestors present in the contemporary conversation.”

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019)

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the 1950s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color.

Brathwaite, who passed away in 2023, was born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance. Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath founded the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. AJASS was a collective of artists, playwrights, designers, and dancers; Grandassa Models was a modeling agency for Black women. Working with these two organizations, Brathwaite organized fashion shows featuring clothing designed by the models themselves, created stunning portraits of jazz luminaries, and captured behind-the-scenes photographs of the Black arts community, including Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Miles Davis.

Black Is Beautiful is is the first-ever monograph of his work, showcasing Brathwaite’s riveting message about Black culture and freedom. “To ‘Think Black’ meant not only being politically conscious and concerned with issues facing the Black community,” writes Tanisha C. Ford, “but also reflecting that awareness of self through dress and self-presentation. . . . [They] were the woke set of their generation.”

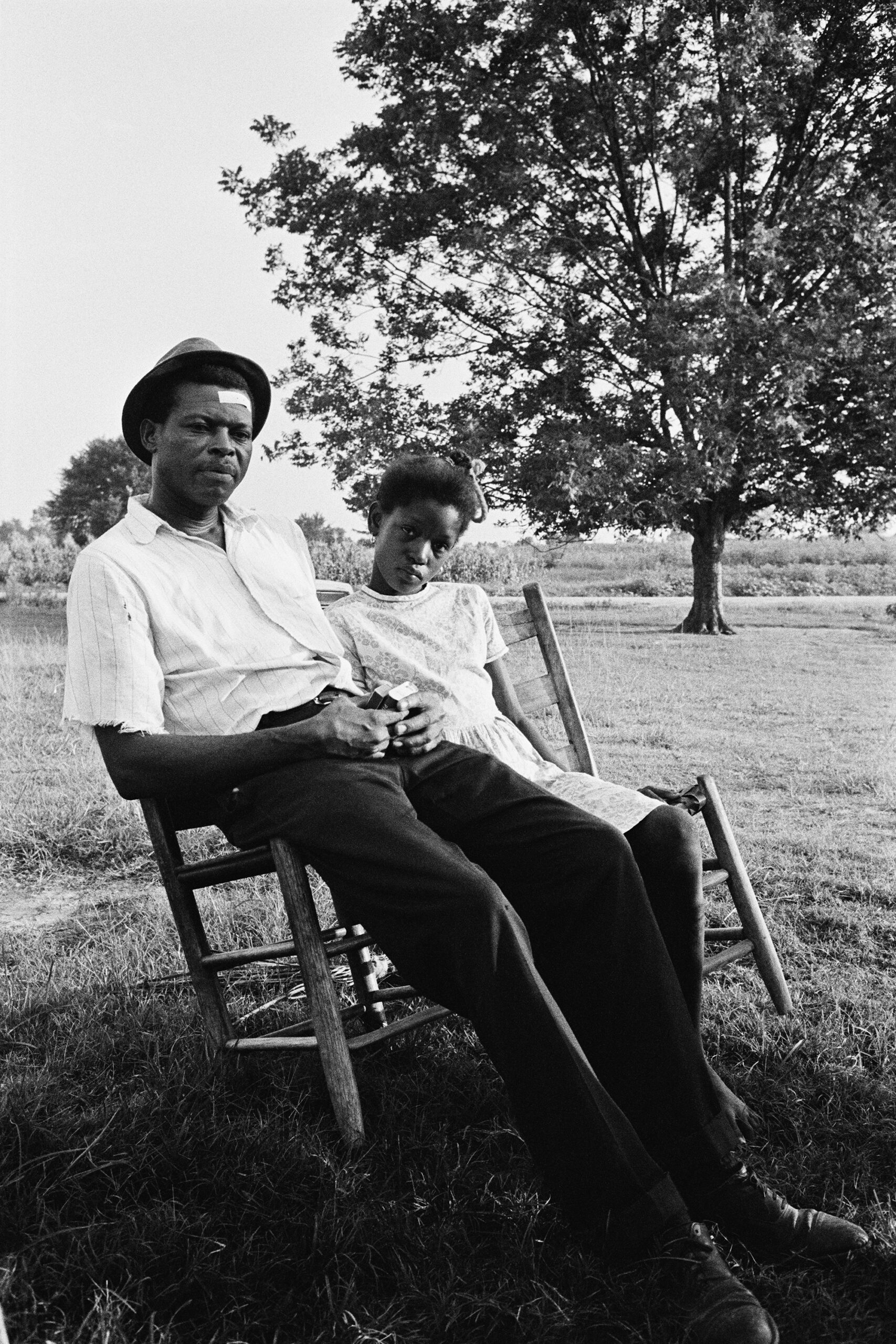

Courtesy the Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole: The True America (2024)

After fleeing South Africa to publish his landmark book House of Bondage in 1967 (reissued by Aperture in 2022) on the horrors of apartheid, Ernest Cole became a “banned person” and resettled in New York. Supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation, Cole photographed the city’s streets extensively, chronicling daily life in Harlem and around Manhattan. In 1968 he traveled across the country to cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Memphis, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, as well as to rural areas of the South, capturing the activism and emotional tenor in the months leading up to and just after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. These photographs reflect both the newfound freedom Cole experienced in the US and the photographer’s incisive eye for inequality as he became increasingly disillusioned by the systemic racism he witnessed.

Cole released very few images from this body of work while he was alive. Thought to be lost entirely, the negatives of Cole’s American pictures resurfaced in Sweden in 2017 and were returned to the Ernest Cole Family Trust. The True America marks the first time these photographs have been brought together in a major publication. With more than 260 previously unpublished images, this compilation redefines the scope of Cole’s work.

Courtesy the artist

Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (2023)

Awol Erizku’s interdisciplinary practice references and reimagines African American and African visual culture, from hip-hop vernacular to Nefertiti, while nodding to traditions of spirituality and Surrealism. Mystic Parallax is the first major monograph to trace the rising artist’s career. Spanning over ten years, the volume blends together his studio practice with his work as an in-demand editorial photographer, including his conceptual portraits of Black culture icons such as Solange, Amanda Gorman, and Michael B. Jordan.

Throughout his work, Erizku consistently questions and reimagines Western art, often by casting Black subjects in his contemporary reconstructions of canonical artworks. “I always think about my work as a constellation, and a new piece is just another star within the universe,” he asserts in his wide-ranging conversation with curator Antwaun Sargent, included in the book. “This goes back to the idea of a continuum of the Black imagination. When it’s my turn, as an image maker, a visual griot, it is up to me to redefine a concept, give it a new tone, a new look, a new visual form.”

Courtesy the artist

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s first book, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in an essay for the book. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-on C-print.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019)

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in fashion and art today. The book highlights the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation—including Tyler Mitchell, the first Black photographer to shoot a cover story for Vogue; Campbell Addy and Jamal Nxedlana, who have founded digital platforms celebrating Black photographers; and Nadine Ijewere, whose early series title The Misrepresentation of Representation says it all.

From the role of the Black body in media to cross-pollination between art, fashion, and culture, and to the institutional barriers that have historically been an impediment to Black photographers, The New Black Vanguard opens up critical conversations while simultaneously proposing a brilliantly reenvisioned future. “Often in this culture, when we think about the work of Black artists, we almost never think about, How do we celebrate young Black artists? And I wanted to change that,” Sargent states. “I wanted to say that what was happening right now with these very young artists is significant. It has shifted our culture, it has shifted how we think about photography, and it has shifted who gets to shoot images.”

Courtesy the artist and Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (2018)

South African artist Zanele Muholi is one of the most powerful visual activists of our time. Muholi first gained recognition for their 2006 series Faces and Phases that documents the LGBTIA+ community, creating ambitiously bold portraits in an attempt to build a visual history and remedy Black queer erasure. From there, Muholi began to turn the camera inward, beginning a series of evocative self-portraits brought together in their 2018 monograph Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness.

Muholi’s self-portraits are radical statements of identity, race, and resistance. Using props and materials found in their immediate environment, Muholi crafts starkly contrasted frames that directly respond to contemporary and historical racisms—while also providing a platform for self-discovery. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified,” Muholi states. “To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.”

Courtesy the artist and Webber Gallery, London

Zora J Murff: True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) (2022)

Zora J Murff’s photographs construct an incisive, autobiographic retelling of the struggles and epiphanies of a young Black artist working to make space for himself and his community.

Since Murff left social work to pursue photography over a decade ago, his work has consistently grappled with the complicit entanglement of the medium in the histories of spectacle, commodification, and race, often contextualizing his own photographs with found and appropriated images and commissioned texts.

True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) continues this conversation, examining the act of remembering and the politics of self, which Murff describes as “the duality of Black patriotism and the challenges of finding belonging in places not made for me—of creating an affirmation in a moment of crisis as I learn to remake myself in my own image.”

Courtesy the artist and Aperture

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020)

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century African American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1979, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes for the New Yorker, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

Courtesy the artist

Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal (2018)

Throughout Hank Willis Thomas’s prolific and interdisciplinary career, his work has explored issues of representation, perception, and American history. At the core of his practice is the ability to parse and critically dissect the flow of images that comprise American culture, with particular attention to race, gender, and cultural identity.

Since his first publication, Pitch Blackness (Aperture, 2008), Thomas has established himself as a significant voice in contemporary art. His collaborative projects include Question Bridge, a transmedia project that uses video to facilitate conversations among Black men, and the artist collective For Freedoms.

In 2018, Aperture and the Portland Art Museum copublished All Things Being Equal, the first in-depth overview of the artist’s extensive career. Featuring over 250 images from his oeuvre, the volume highlights Thomas’s diverse range of visual approaches and mediums—from advertising and branding, civil-rights and apartheid-era photography, and sculpture, to public-art projects and more.

Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Muse by Mickalene Thomas (2015)

Mickalene Thomas’s large-scale, multitextured tableaux of domestic interiors and portraits subvert the male gaze and assert new definitions of beauty. Thomas first began to photograph herself and her mother as a student at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut—which became a pivotal experience in her creative expression as an artist.

Since then, throughout her practice, Thomas’s images have functioned as personal acts of deconstruction and reappropriation. Many of her photographs draw from a wide range of cultural icons, from 1970s “Black Is Beautiful” images of women to Édouard Manet’s odalisque figures, to the mise-en-scène studio portraiture of James Van Der Zee and Malick Sidibé. Perhaps of greatest importance, however, is that Thomas’s collection of portraits and staged scenes reflect a very personal community of inspiration—a collection of muses that includes herself, her mother, her friends and lovers—emphasizing the communal and social aspects of art-making and creativity that pervade her work.

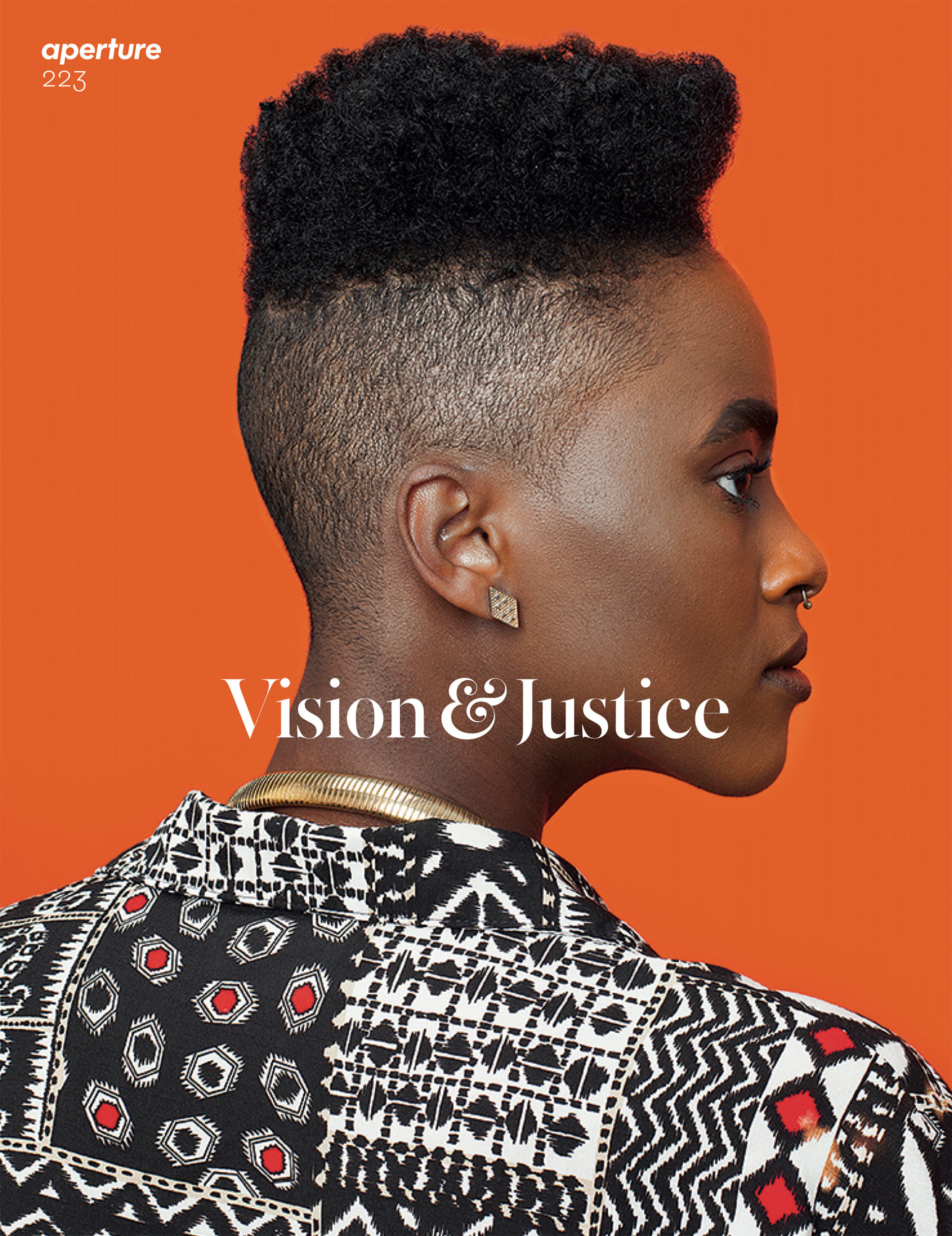

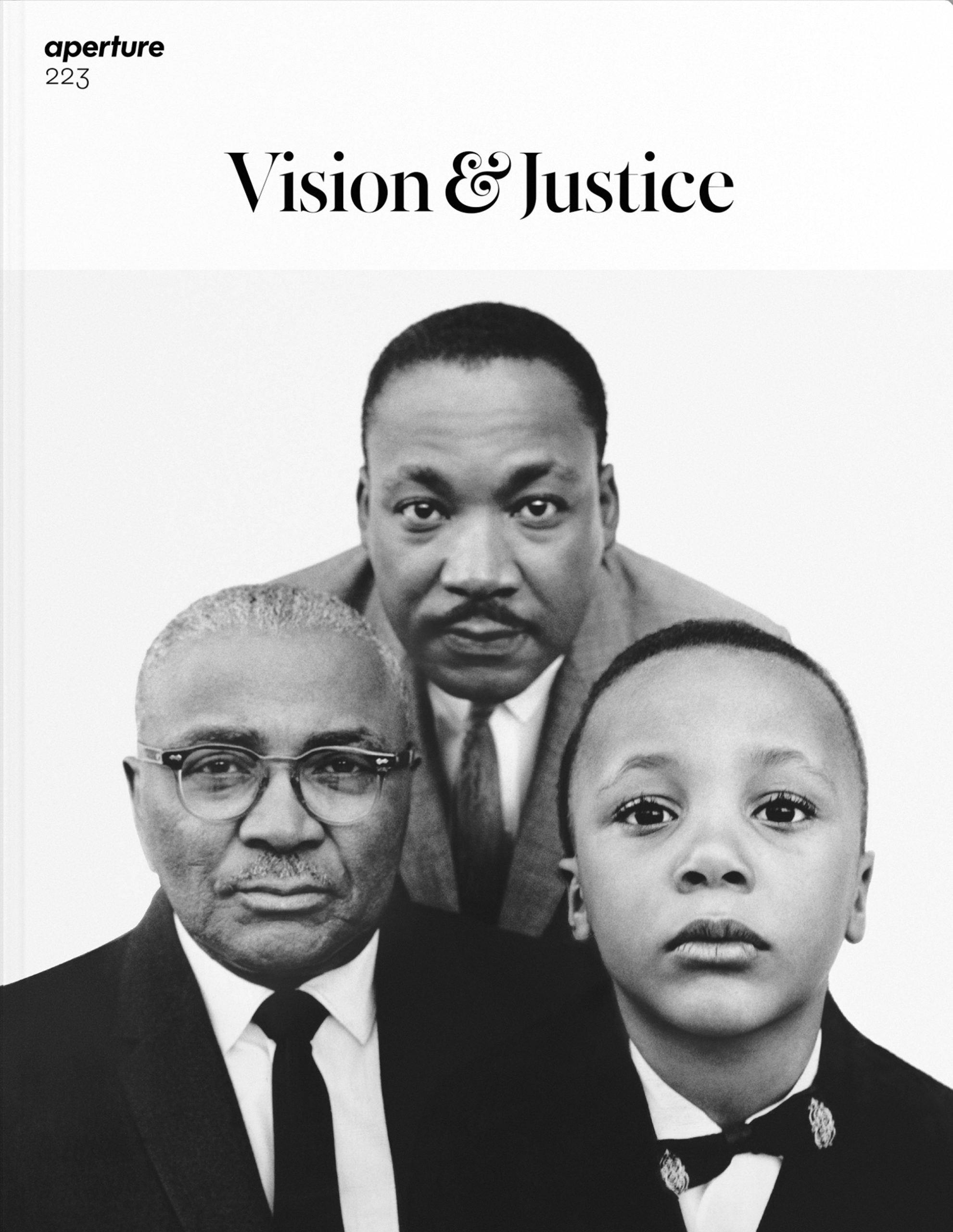

Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice” (Summer 2016)

The art historian, curator, and writer Sarah Elizabeth Lewis guest edited Aperture’s summer 2016 issue, “Vision & Justice,” a monumental edition of the magazine that sparked a national conversation on the role of photography in constructions of citizenship, race, and justice. The issue features a wide range of photographic projects by artists such as Awol Erizku, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Lyle Ashton Harris, Deana Lawson, Jamel Shabazz, Hank Willis Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis; alongside essays by some of the most influential voices in American culture, including Vince Aletti, Teju Cole, and Claudia Rankine. “Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil,” writes Lewis. “It is the artist who knows what images need to be seen to affect change and alter history, to shine a spotlight in ways that will result in sustained attention.” In 2019, Aperture worked with Lewis to create a free civic curriculum to accompany the issue, featuring thirty-one texts on topics ranging from civic space and memorials to the intersections of race, technology, and justice. Taking its conceptual inspiration from Frederick Douglass’s landmark Civil War speech “Pictures and Progress” (1861)—about the transformative power of pictures to create a new vision for the nation—the curriculum addresses both the historical roots and contemporary realities of visual literacy for race and justice in American civic life.

See here to browse the full collection of featured titles