Essays

Dayanita Singh Finds Common Ground in the Work of Two Architects

In her long-term series on Geoffrey Bawa and Bijoy Jain, Singh offers a world in which the aspirations of modernism are realized.

Architecture and photography have always been intimately connected. These media share a few fundamentals: impacts of light and air, the balance of surface and depth, interiority and exteriority, and how these relations are mediated by the human body. Attending to such concerns has guided the expansive, fluid artistic practice of Dayanita Singh, whose open-ended approach to the photographic image has led to distinctive architectural modes of display. Encased in teak frames, screens, and boxes that often double as display cases which can be placed on walls and bookshelves, Singh’s photographs circulate in modular forms that are adjustable to individual taste. They underscore how images accrue meaning over time, as people live and grow alongside them.

“To me, a photograph is something you touch and you move and it warps and it gets dented: it’s alive,” Singh remarked in a recent interview. Recounting her upbringing in India, she notes how her family’s many photographs extended beyond stuffed albums and were wedged under the glass tabletop in their living space, where they seemed to vibrate with their own physicality, like another form of furniture. Her long-term engagement with the architects Geoffrey Bawa and Bijoy Jain draws from this personal history and aligns with a longer arc of modernist photography and its fascination with portraying surface, depth, and environment to extend the capacity of human vision. In her corpus of photographs made in conversation with Bawa’s and Jain’s respective designs, Singh’s ever-curious photographic eye reveals shared principles between the two architects—commitment to the use of local materials, respect for craftspeople and traditions, seamless integration with the surrounding environment—while allowing their practices to remain fully distinct.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Born in 1919 in colonial Ceylon, Geoffrey Bawa traveled extensively throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe in the years after World War II before returning home, where he purchased a former rubber plantation in the southern coastal town of Bentota. He hoped to turn it into a garden villa like the ones he had seen in Italy. Realizing the complexity of the task, Bawa apprenticed with the local architect H. H. Reid and went on to complete studies in architecture in England between 1953 and 1956. Bawa became a partner in Reid’s firm in Ceylon in 1957, and throughout the 1960s and 1970s designed private homes, hotels, and schools across the island—renamed Sri Lanka in 1972—and later in Indonesia, Singapore, and Fiji.

Singh recalls her first visit to the Kandalama Hotel—designed by Bawa on the outskirts of Dambulla, in 1994—as a kind of déjà vu experience. Her arrival at the Lunuganga estate in Bentota felt similarly fated. For her Bawa Series (2016– ongoing), Singh photographed the interiors of Bawa’s estate, as well as a modernist domicile he designed for the artist Ena de Silva in 1960, which was moved brick by brick from Colombo to Lunuganga.

Singh’s photographs highlight Bawa’s meticulous selection of materials to create contrast, a hallmark of the so-called tropical modernism associated with his legacy. Consider how the rough, jagged surface of an outside portico’s tear-shaped stone pillar harmonizes with the whitewashed walls and glass windows, or the way the curves of the molded chairs in Bawa’s living room balance its wide floor-to-ceiling windows, shaded by reed screens.

Singh’s photographs highlight Bawa’s meticulous selection of materials to create contrast, a hallmark of the so-called tropical modernism associated with his legacy.

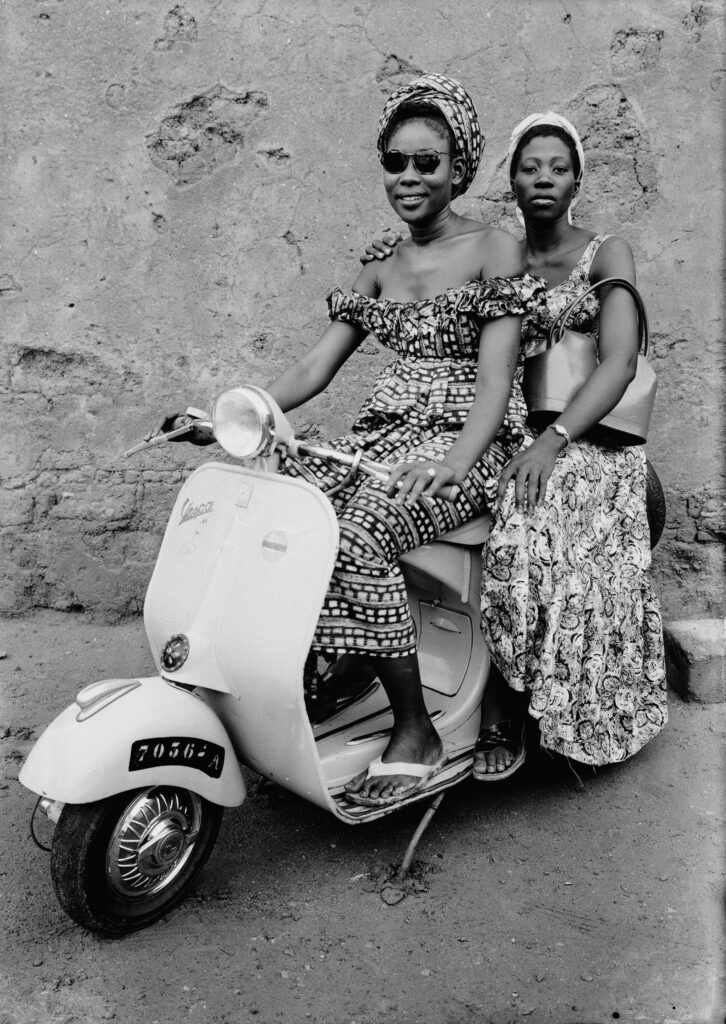

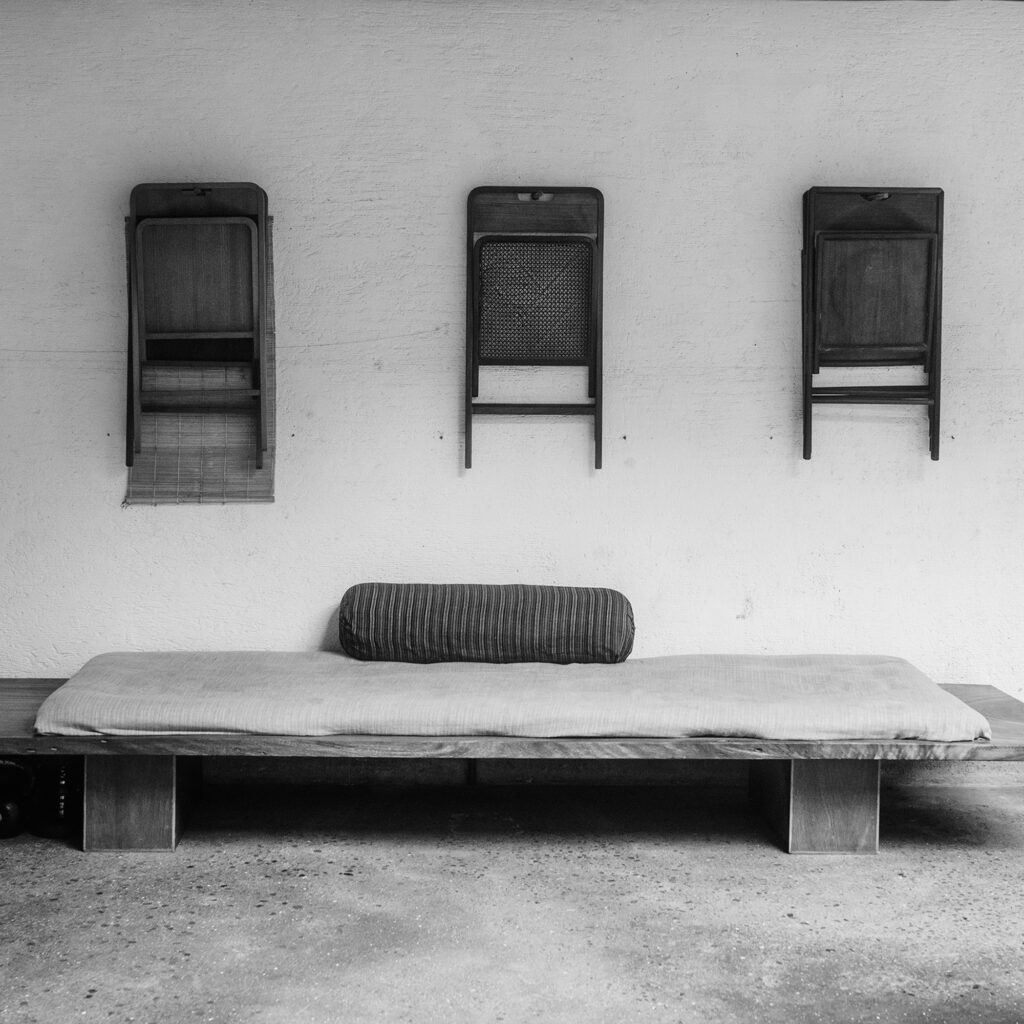

Harmony with the local environment is also central to the practice of Mumbai-based Bijoy Jain, whose studio work was recently the subject of an exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. Born in 1965, Jain studied architecture in the United States and worked for Richard Meier before founding an eponymous firm in 1995, later renamed Studio Mumbai. For Studio Mumbai (2019–ongoing), Singh made a series of images at the former tobacco warehouse in the south Mumbai enclave of Byculla that serves as Jain’s studio space. “There is something I am seeking when I am photographing architecture,” she says. “It’s not the architects, but this exhalation that I find again and again in Studio Mumbai’s work.” Singh trained her camera on surface textures of concrete and wood to draw out formal homologies within the studio: a large overstuffed spherical form rhymes with a nearby wall hanging, the folds of the fabric creating further associations. In one image, a trio of folding chairs hangs on a wall above a low wooden daybed.

Jain, who acknowledged his respect for Bawa’s precision and dogged devotion to local material and craft in his 2012 Geoffrey Bawa Memorial Lecture, illustrates here that a pared-down approach can open up new possibilities. That ethos is not unlike Singh’s, whose spare, monochromatic images of domestic space highlight how constraint offers a way to channel creative energies and draw new connections across different forms and media. Metabolizing the elemental principles shared by photography and architecture, and allowing these connections to take center stage, Singh’s images offer a world in which the loftiest aspirations of modernism—to create better living conditions through careful design—are realized.

All photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”