Interviews

Grace Wales Bonner on the Photographers That Inspire Her Visionary Fashion Design

In an exclusive interview, the influential designer speaks about her artistic collaborations with Liz Johnson Artur, Tyler Mitchell, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya—and how she uses images to salute the past and imagine the future.

Fashion’s constant churn may mean that nods to the past come and go without much fanfare. But for the celebrated London-based designer Grace Wales Bonner, cultural references are conjured with careful intention. They become a form of reckoning and homage, a way to center Black artists and thinkers within a generous, ever-growing constellation of ideas. One clothing collection from 2019 was named Mumbo Jumbo, after Ishmael Reed’s 1972 novel.

Writing on Wales Bonner in The New Yorker, the critic Hilton Als reflects that she “aims to make the broken history of the Black artist and intellectual in African, European, and American culture whole.” She does this through her diligent research, an eponymous label, and high-profile collaborations with other companies, such as Christian Dior and Adidas, that expand her reach.

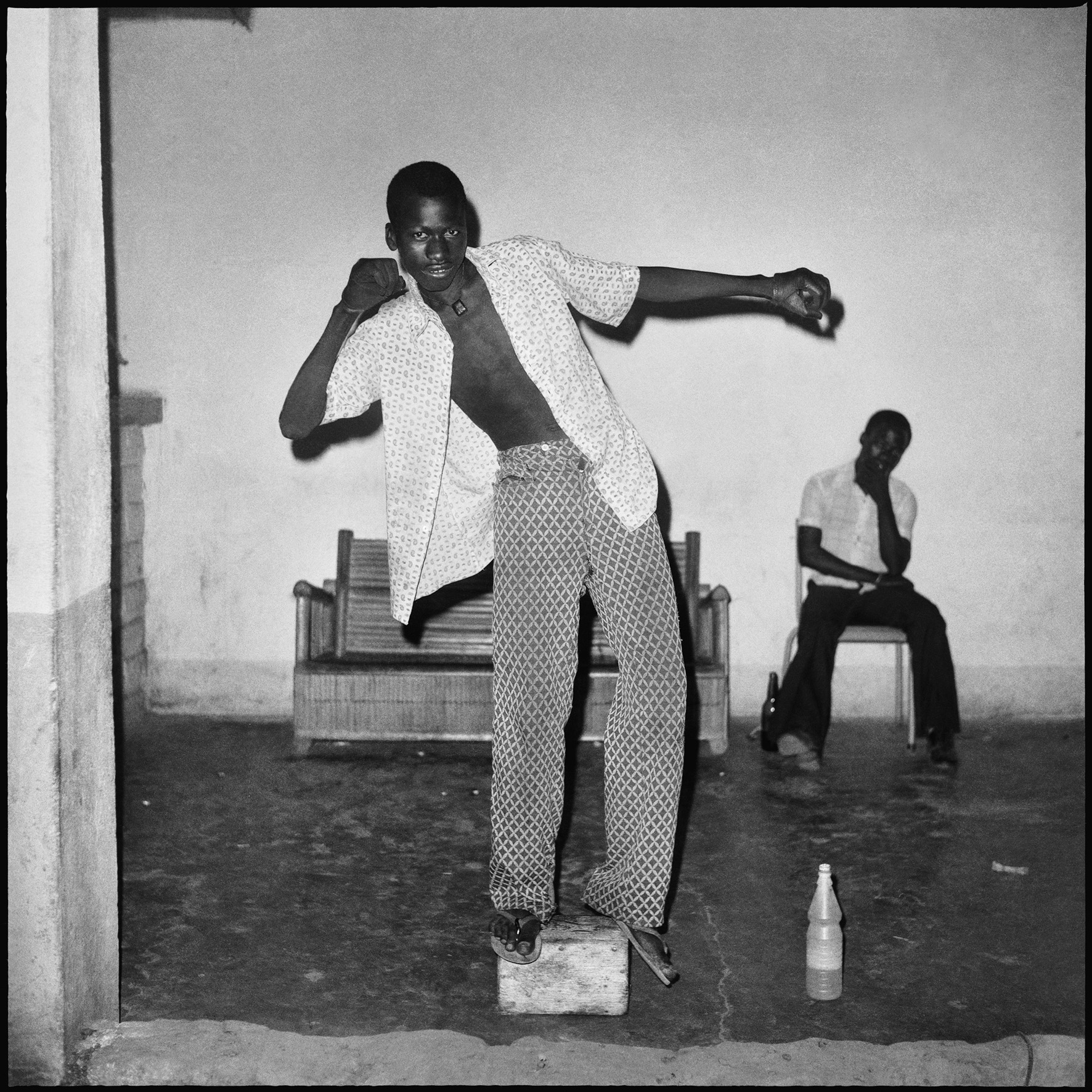

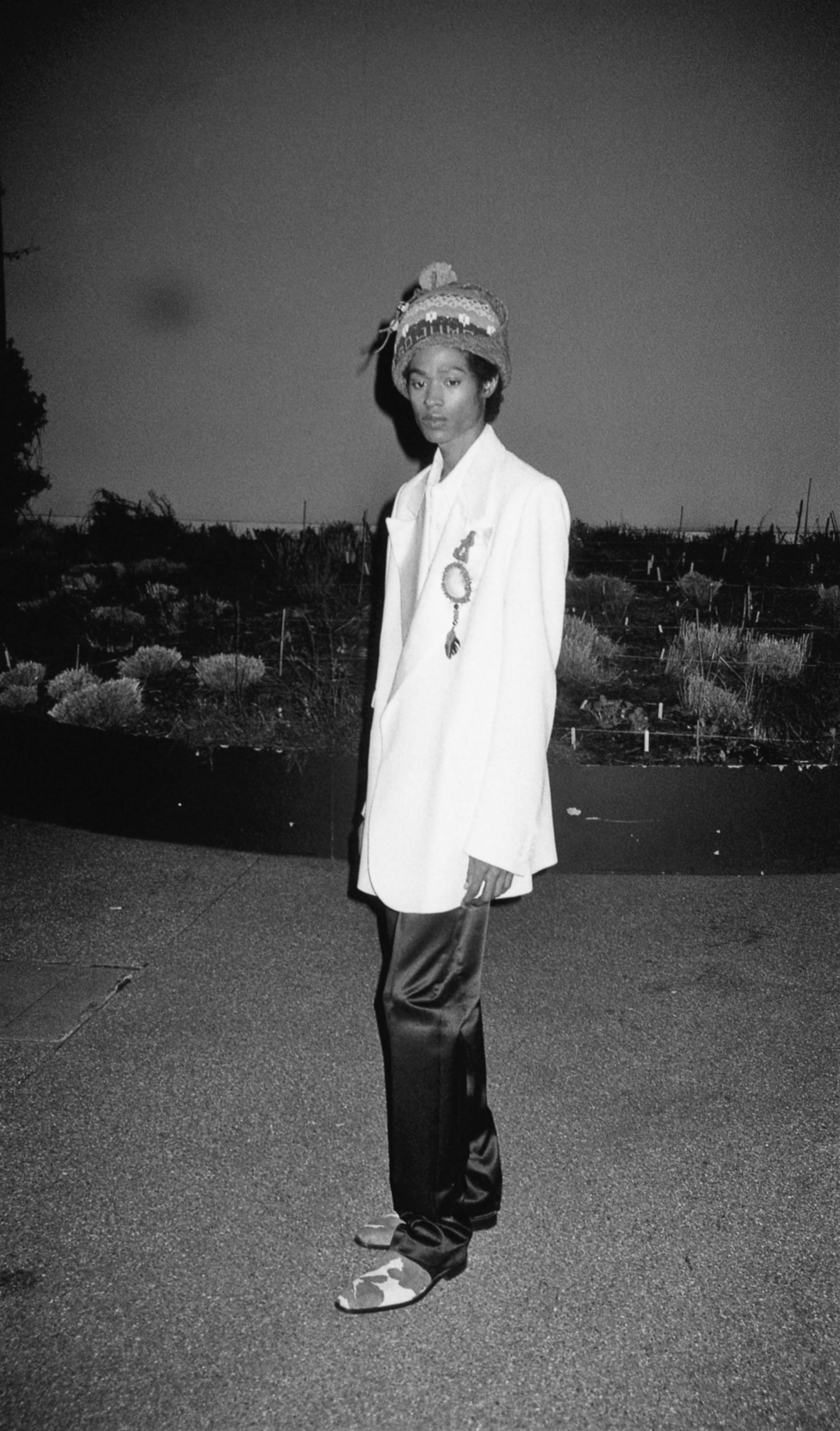

Photography is central to this project. Past collections have been inspired by John Goto’s 1970s-era portraits of British Caribbeans of African descent and Sanlé Sory’s stylish studio images from Burkina Faso. Wales Bonner has recently collaborated with Liz Johnson Artur, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Tyler Mitchell. Her interest in working with artists extended further in 2019, when she presented a multimedia exhibition at London’s Serpentine Galleries that explored relationships between visual art, spirituality, and mysticism. Last August, the curator Ekow Eshun spoke with Wales Bonner about how she uses design to salute the past and imagine the future.

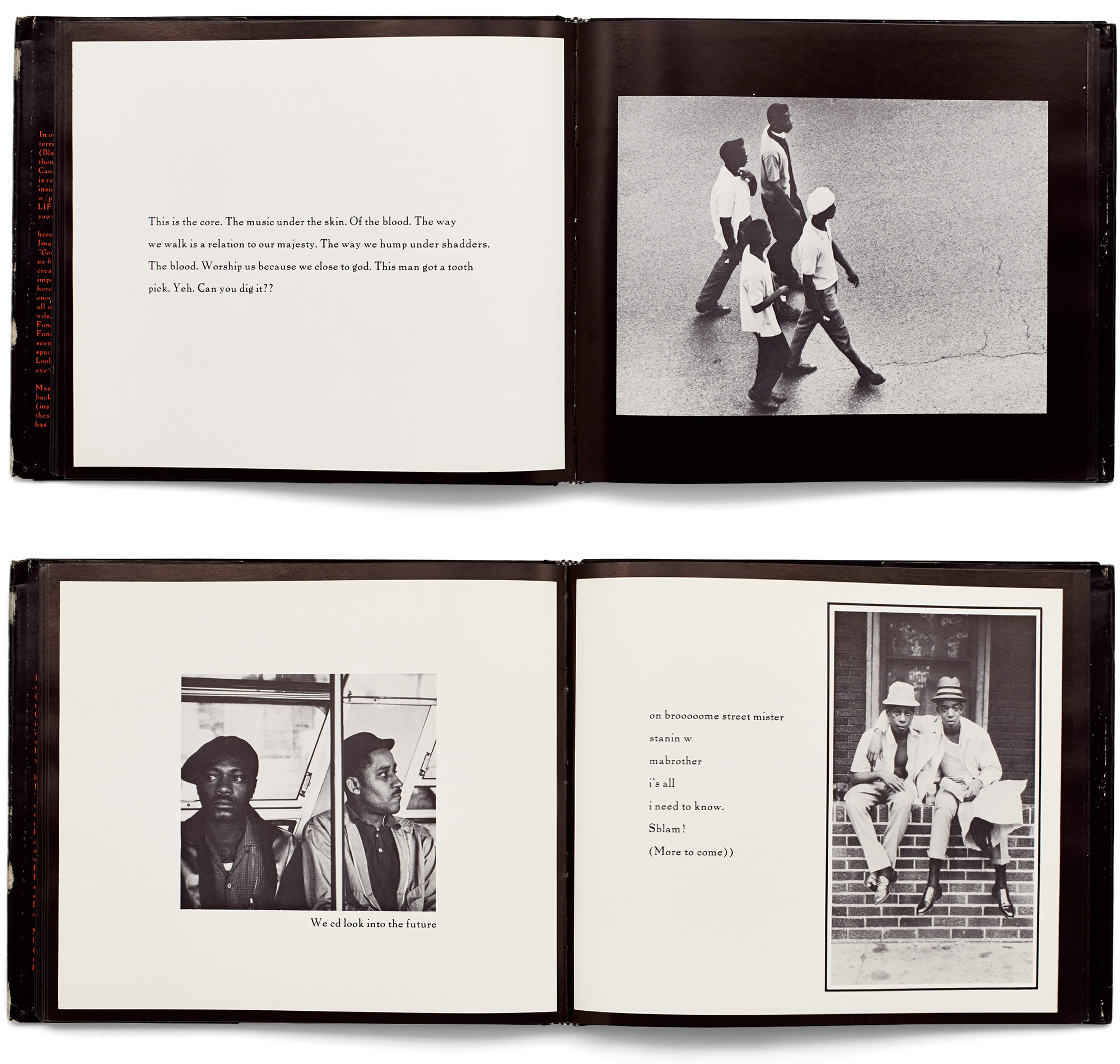

Ekow Eshun: When you graduated from Central Saint Martins, in 2014, you bought a copy of In Our Terribleness, the 1970 Amiri Baraka and Billy Abernathy book that combines poetry and photography. Why that book?

Grace Wales Bonner: I remember it was quite an investment after I’d graduated. I got a copy signed by Baraka. I guess it shows my priorities and what I wanted to spend significant money on at a time when I probably didn’t have any money. There was the poetry, or the Ebonics, the sound of Blackness, and then also a visual record and the poetry and photography mirroring each other. The intonation of Baraka’s writing informing the rhythm of the book and the layout. Such incredible photographs, but the poetry has equal strength. It merged a lot of things.

Eshun: Yes, it’s a really striking synthesis of image, text, and design.

Wales Bonner: When I was leaving school, I wasn’t sure if I would be a designer. I thought I could be an art director. I was interested in a holistic way of representing fashion. It wasn’t just about clothing but about clothing in context. There’s a lot that can go into that, whether it’s thinking about the sounds that you’re hearing at the time, or the literature that you may be exposed to. I was also drawn to unselfconscious portraiture and photography that gives you a record of style at a certain time. Images that weren’t consciously fashion images. Another book that has that kind of format is Roy DeCarava’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), with poems by Langston Hughes. I picked up on the lineage of that book, where photography and poetry have some relationship, which is something I explored with Rhapsody in the Street, a magazine I curated. It’s not about images in isolation, but it’s about the freedom to interpret with poetry using a more abstract or romantic imagining around these images, not necessarily in a contextual or historical approach.

© the artist

Courtesy the artist; DOCUMENT, Chicago; Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich; and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Eshun: Let’s discuss the photographers you’ve chosen to collaborate with: Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Liz Johnson Artur, and Tyler Mitchell. What led you to them?

Wales Bonner: There is a sense of curation around the people I work with, but there’s often a natural and emotional relationship that is a starting point. For example, Paul Sepuya—I saw his exhibition in New York. This was 2017 or 2018. I was really moved by it, by the attention to detail in the aesthetics, the frames, the space around the images. I could tell that he had incredible taste. I just emailed him and said, “I’m a really big fan, and I’d love to meet.” I ended up going to his studio in LA. He’s so informed in everything he does. I do think about photographic archives, and he’s someone who engages with archives. He told me that he used to archive older Black artists’ work for them.

Eshun: In your office, which I’ve been to, you have a lot of books that you’re looking at and thinking about. What is compelling to you about that process of archiving?

Wales Bonner: For me, researching is an artistic practice for myself—or even a spiritual practice. That’s the art form that I feel like I connect with most naturally. But I also like the fact that it doesn’t need to result in something for Wales Bonner clothing.

I want to create more space for that practice. Within fashion, there is a specific cycle, an output and a pace to it. I’ve been looking at how to safeguard my process. Actually, I now have a grant for the next four years to focus on research.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Wales Bonner: What I do is connected to a lineage of artists and writers, and so informed by that history that it’s about transparency— revealing that process and documenting it quite methodically so that people can follow those threads. That was an intention at the 2019 Serpentine exhibition [Grace Wales Bonner: A Time for New Dreams], to show how different artists have informed a development of thinking. I want to point to those things. And it’s more for my own process really, to mark certain moments. It is often fragments: a memory of a text or an isolated image. There’s a lot of space to fill in gaps and to create worlds around these references.

The way I think about references is that they’re a library. Everything that’s in there is important.

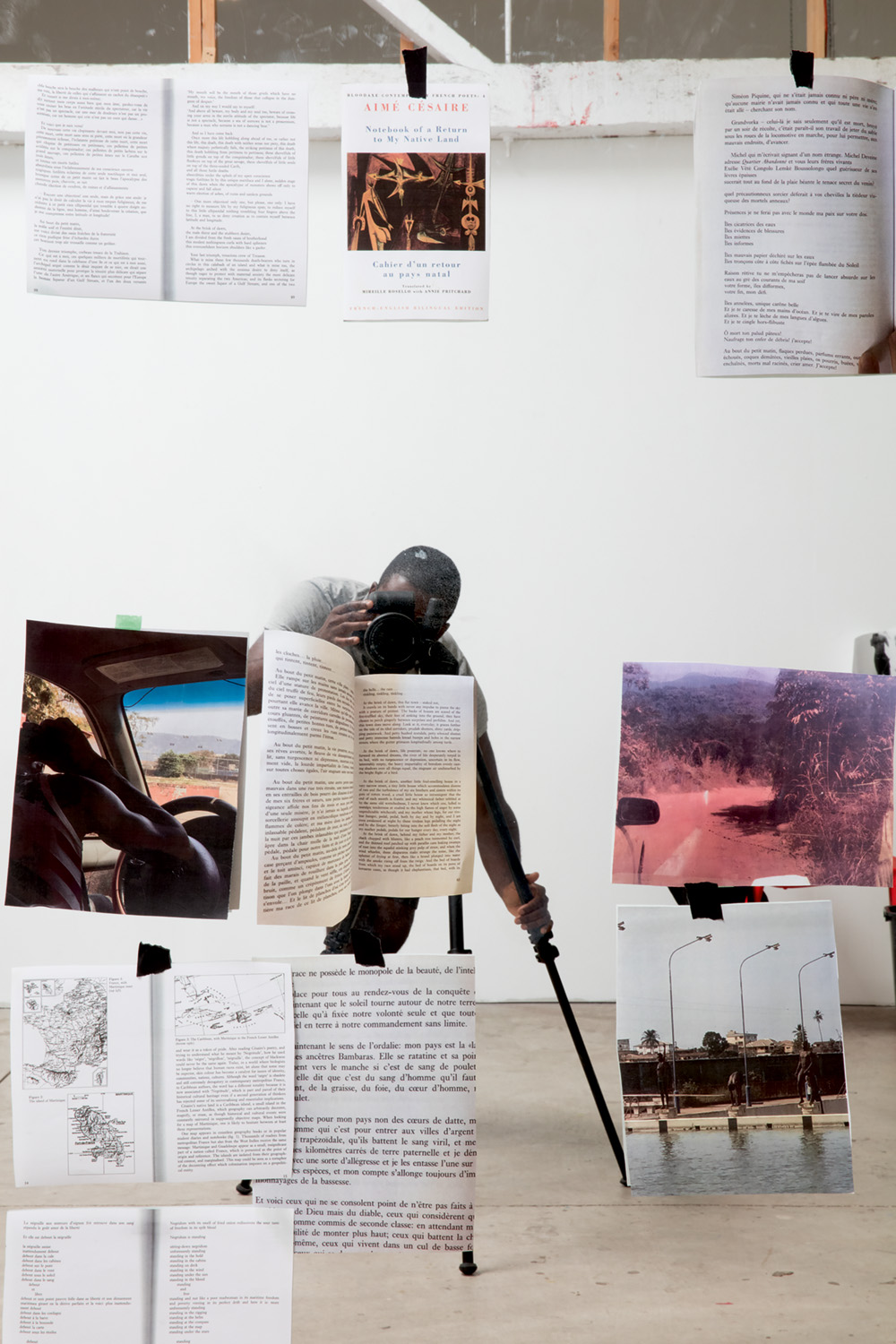

Eshun: Can you talk about some of the visual decisions you made for the Serpentine show in terms of working as an artist and a curator rather than as Grace Wales Bonner, the fashion designer?

Wales Bonner: There’s definitely a different process. The actual making connections between artists crosses over, but with that exhibition, I wanted to transform the gallery space into a place for reflection and meditation. I was thinking a lot about the idea of a portal, whether that’s a spiritual assemblage, like, say, a shrine, that allows you to interact or have communion, or whether that’s a musical meditation that transports you. Ben Okri wrote invocations for the shrines, which is how I loosely thought about the collection of objects and artworks. He also wrote these interruptions within the space that were on the ceiling or in places you wouldn’t expect they would be. There was a sound shrine that I made, which would come on only at certain times. There was this element of the unexpected, for things not to be perfectly neat, for there to be space to be subtly disruptive. More than anything, it was about an emotional quality and how people would feel in that space.

Eshun: The photographer Liz Johnson Artur made a kind of shrine, too, for the exhibition. What did you see in her work?

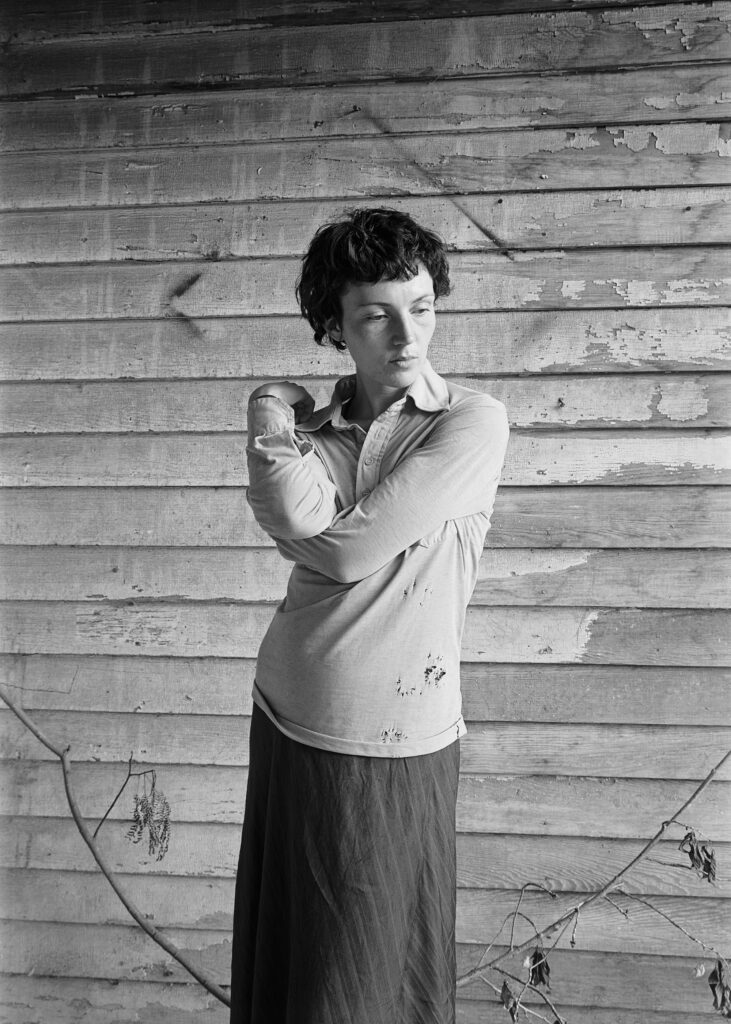

Wales Bonner: I think she’s an exceptional artist and someone who has archived history. For me, it’s also about a level of excellence in her photography. That’s probably a connection among the people I tend to drive to, that they are mastering their craft. Sometimes I feel out of my depth with the talents of the artists I’m working with, and maybe that’s good and motivating. With Liz, photography is almost a material to make art from. The way that she presents her imagery is elaborate.

Courtesy the artist

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Eshun: Some of your collection shows have directly referenced historical photographers: John Goto in your Lovers Rock Autumn Winter 2020 collection and Sanlé Sory in Volta Jazz for Spring Summer 2022. You were looking at their projects from the 1970s. Why select a particular moment in time?

Wales Bonner: Certain photographic records are timeless—like Goto’s pictures. Actually, his Lovers’ Rock series from 1977 is so influential because it records a moment in time, and it’s connected to a community. You start to see these different characters and a very clear record of what people were wearing and what people were listening to. Certain times, it might be inspirational, but for me it’s not really seasonal. It’s a kind of timeless reference.

Sanlé Sory, in the fashion context, has been very influential as well, but he might not always be given visibility in a direct manner. The way I think about references is that they’re a library. Everything that’s in there is important. All these things become quite embodied.

Eshun: And there’s also photography as collaboration, as with someone such as Tyler Mitchell, whom you invited to photograph a collection. What might lead you to collaborate with a certain photographer?

Wales Bonner: I prefer continuity. Liz was part of the Serpentine exhibition, but she’d been photographing my designs since 2019 in an informal setting. It’s critical for me to have that continued dialogue with people over time. With Tyler Mitchell as well. It’s never a one-off, really. I want to have relationships with people. We’re developing together; there’s an evolution in real time. I do have a long view in that sense, whether that’s a view on the past and how it is influencing the present or it’s creating something that has longevity.

Courtesy Wales Bonner

Eshun: We’ve talked about your role as an archivist, researcher, historian, artist, curator, and fashion designer. How do you think of yourself?

Wales Bonner: I would say researcher, as a grounding practice—and research being an artistic practice. And then, I want to consider how that can inform different outcomes, whether that becomes a musical experience or a fashion show or a garment or a publication. That’s the starting point.

Eshun: You recently collaborated with the painter Kerry James Marshall.

Wales Bonner: I would say Kerry James Marshall is probably the artist who has influenced me most, even my wanting to create Wales Bonner.

Eshun: Let’s dwell on that for a moment. Why?

Wales Bonner: He has seen within art history the absence of Black presence. And he has been strategic in order to influence and infiltrate and be part of something at a very high level. Even the way that he makes his paintings large in scale so that in an exhibition space there’s a physical Black presence. He’s understood exactly what knowledge and what resources are needed to have such a position. I saw a similar lack within the fashion space. I wanted to create a fashion brand that could represent a highly sophisticated image of a Black cultural perspective. So, yeah, he’s been really influential to my work and my understanding of beauty.

Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

Courtesy Wales Bonner

Eshun: Is there a strategy on your part in terms of making visible the kind of references that we talked about but also of honoring those partnerships that you continue to develop over a number of years?

Wales Bonner: I wouldn’t necessarily say that’s really strategic, because I feel like it’s a quite natural part of my process. It’s part of how I think about time probably, and connecting past, present, future.

Eshun: There is an insistence on inscribing a Black presence and asserting the significance of those photographers or those other image makers and artists as figures whose work changes the culture as a whole.

Wales Bonner: I’m very interested in beauty, or in having a specific representation of beauty, but it’s also important to show that this is not at all new. There’s so much evidence, so many records. There’s a vast body of work over history. That’s the frame I’m exposed to. For me, there is a sense of thinking about history and just revealing what’s there—what’s always been there.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”