Essays

How An-My Lê Makes Meaning from History’s Psychic Debris

Ocean Vuong reflects on Lê’s photographs of Vietnam and the US, considering how the artist masterfully uses blurred motion and stillness to reclaim the semiotics of war.

It is tempting, when considering An-My Lê’s body of work, now spanning three decades, to mention the depth and scope of the projects, which include vexed approaches to landscape, still life, portraiture, and detailed, photographic studies of social and industrial processes. However, such variegated modes are already evident in Lê’s first monograph from twenty years ago, Small Wars. While debut projects, in any medium, often bear the crude joints where nascent, searching forays were pruned back by mentors or colleagues in graduate workshops or formal schooling, Lê’s first effort marks a subversive, even defiant, commitment to variations in subject, style, and obsessions. It is immediately sure-footed, richly intelligent, and momentous in its seeking.

Bringing together three projects—all with distinct approaches—that cross two continents and multiple tonal gradients, what immediately becomes clear is Lê’s dismissal of the novice artist’s anxiety to find and establish a signature, and in theory “marketable,” voice and style. And while Lê’s stylistic language is remarkable across the entire book, she has decidedly allowed the project’s inquiry to determine how these frames are shot, refusing to warp them into the narrow cage of affect and thesis. This is perhaps why, despite being shot on a view camera at slower shutter speeds, the photographs give off the distinct sensation of both being found and fashioned at once. It is not surprising, least of all to a fellow Vietnamese refugee like myself, that Lê’s work would be mimetic of the myriad, layered, and often contradictory history of imperial war, humanitarian crisis, and the violence endured by displaced bodies and their memories. What might be seen, often to Western standards of art-making, as a disorientation, or lack of cohesion or logical accretion, is actually an accurate representation of photography’s more global attempt to fashion meaning, however tenuous, out of history’s material and psychic debris.

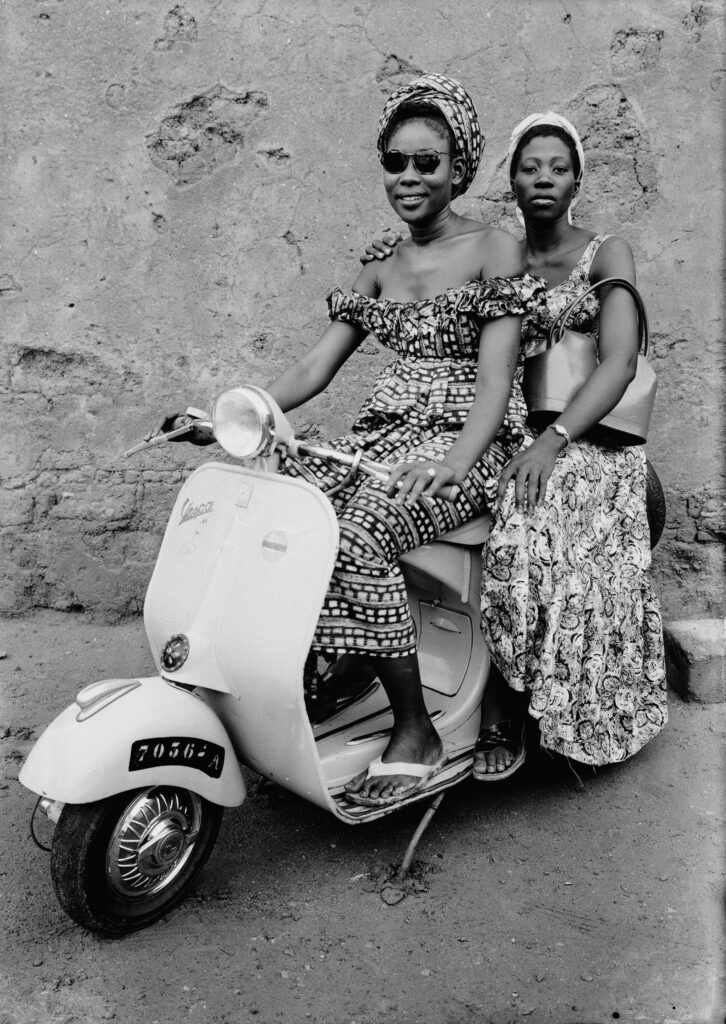

Most striking of these techniques is Lê’s masterful understanding of blur and stillness. In one frame, a Vietnamese boy aims a slingshot toward the branches of a tree, the coiled charge of his body and the sling’s flexion giving the scene an anticipatory torque. The man to the left is blurred in motion, his presence more weather-like and haunting. In another shot of a typical apartment courtyard in Ho Chi Minh City, a man crouches in critical focus while others, caught in the flow of an impromptu soccer game, foam around him, their gestures both graceful and ghostly, giving a scene of recreation the finest touch of elegy and loss. The tension of stillness as agency, pleasure, play, and rest are potent treatments of the Vietnamese body, whose presence in American media has often been trafficked as corpses. The stillness Lê captures is not one of lifelessness—but of life lived so fully—the arrested movement of these figures, as in another shot of a crowd of people observing a solar eclipse, is a reclamation from the semiotics of war and tragedy.

An-My Lê: Small Wars

60.00

$60.00Add to cart

In a maneuver of potent irony, the book builds on this examination of restful, rejuvenated aftermath in Vietnam toward America’s obsession with its own wars. As the epicenter of conflict grows further away, Lê reveals the desperate, even obsessive, desire for American reenactors to reanimate the war in Vietnam in Virginia, a site of Indigenous oppression, chattel slavery, and a major stage in this country’s own civil war. Though the performance of violence carried out on grounds where actual violence occurred is somehow quintessentially American, throughout the book, Lê troubles the fraught idea of national and cultural authenticity. Who is more real, the Vietnamese carrying on a mundane existence, embodying a seldom-observed ordinariness, or the Americans, enacting the cumbersome, boyish mime of the death machine that established America’s ongoing paradox?

Lê leans into the view camera’s capacity for detail, creating tableaus that, as she’s mentioned in interviews, should be “read” as much as seen. The idea of the photograph offering narrative description is apt considering photography’s historically evidentiary function, but like most “evidence,” meaning is established by composition and context. Here lies Lê’s deft handling of subject matter: her own skepticism for the camera’s ability to tell any complete story, her gaze inflecting not only what is inside the frame but also what’s been left out, either through omission or because it no longer exists.

Lê’s rare achievement is that she makes us see, not just the possibility of the subject, but also the fragility of the frame.

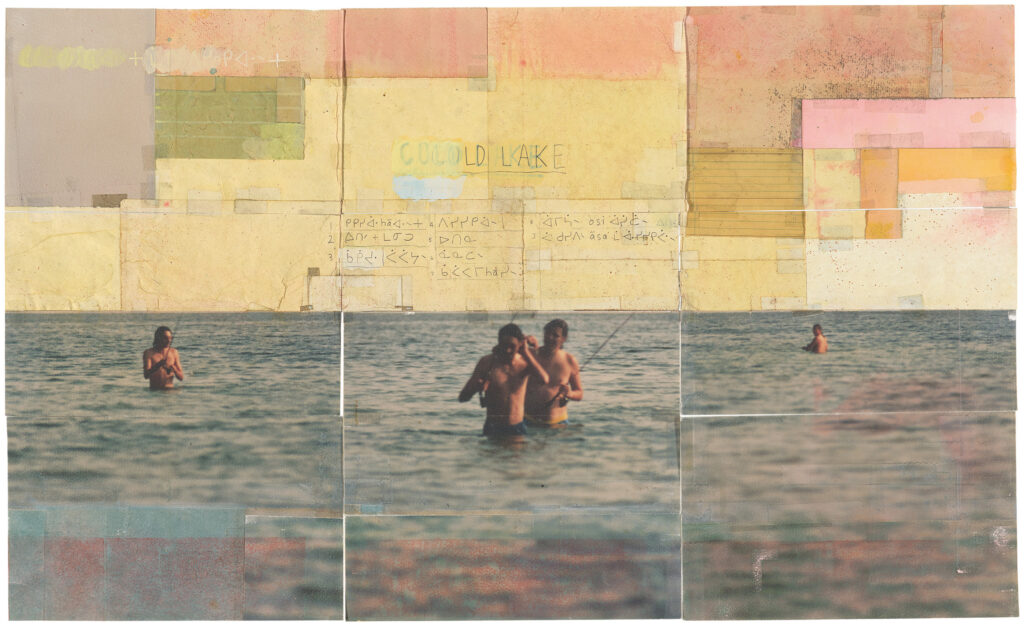

As the book moves toward the final sequence, depicting US military forces training for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, conflicts that parallel the ethical breaches of the war in Vietnam, the frames start to describe the doomed obsession with war as a cyclical curse in the American dream. As the photographs fan out to show Americans simulating war, replete with politicized faux graffiti curling across building facades, Marx’s warning that “history repeats itself, first by tragedy, then by farce” is echoed with chilling accuracy.

But for all its focus on geopolitical shifts, performance, and large-scale composition, Small Wars is, at its core, an autobiographical project—but one that upends the term’s expected conventions. Here, autobiography is not so much confessional revelation of a singular point of view but literally “the writing of a self,” that is, a personhood that includes the trajectory of migration, time, memory, and even the recollection of places where loved ones once inhabited. Here, the self is built through the detritus of a lived life, which includes the ceremonies and rituals of communities Lê has witnessed, both as member and outsider. By drawing with light, as photography’s etymology implies, Lê refigures the lines in the geographical map of her and her family’s migration. Where the diminutive human form common in nineteenth-century American Romantic paintings was meant to entice the viewer toward the capaciousness of “unsettled” land, the same scale in her work reads as an ominous reminder of the Anthropocene’s death drive. For Lê, no personal narrative can be told without the telling of a species-wide propensity for both wonder and destruction. No landscape is without human intervention, often for the worse.

Since a book is, in some ways, a linear form, the presentation of Vietnamese bodies in stillness, rest, potent contemplation and poise, color this monochromatic project, like a die cast in water, with tones of joy, possibility, dignity—and even hope. It is hard to see the tanks in the final section of battlefield exercises and not be reminded of the boy across the world in the first section aiming his slingshot at something outside the frame. Harder still to not see the naivety—one innocuous, the other deadly—in both frames. Lê utilizes the canonical gaze to show us an “elsewhere,” borrowing the omniscient view to reveal who we are, what we always were: small people in small wars trapped in history so large, so momentous, it breaches all compositions. Lê’s rare achievement is that she makes us see, not just the possibility of the subject, but also the fragility of the frame.

This essay originally appeared in An-My Lê: Small Wars, Twentieth Anniversary Edition (Aperture 2025).