Interviews

How Arielle Bobb-Willis Keeps Her Inner Kid Alive

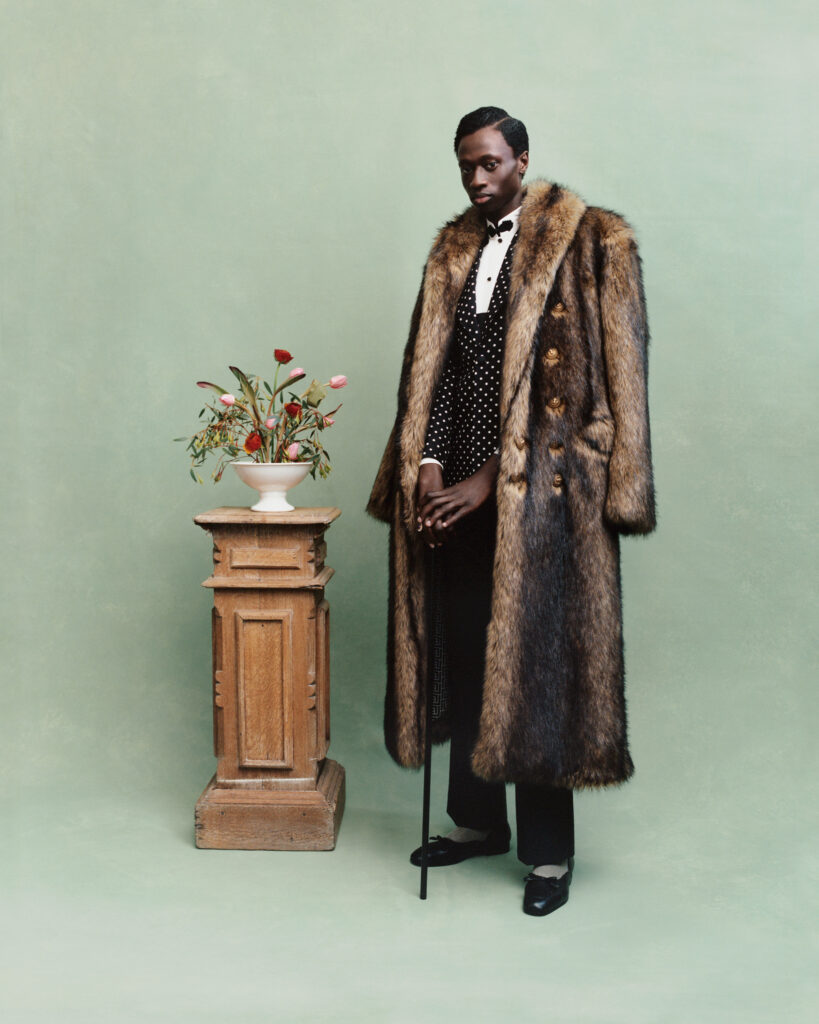

The rising art and fashion photographer’s debut monograph is a vivid statement about color, gesture, and style.

Arielle Bobb-Willis’s first book, Keep the Kid Alive, invites audiences into a brightly imaginative world, filled with dynamic colors, gestures, and unusual poses of the artist’s own creation. Transforming the streets of New Orleans, New York, and Los Angeles into lush backdrops for her wonderfully surreal tableaus, Bobb-Willis makes unforgettable images that expand the genres of fashion and art photography. “I love the idea of seeing Black people represented in an abstract way,” Bobb-Willis says. “It’s important to me to continue to reject the notion that Black expression is limited—or limiting.”

Here, Nicole Acheampong speaks with Bobb-Willis about her entry into photography, her unconventional approaches to styling, and how she keeps her inner kid alive.

Nicole Acheampong: To start, can you tell me about your family?

Arielle Bobb-Willis: I grew up the youngest, with two older brothers. Me being the only girl and the youngest, I definitely kept to myself.

My mom and my dad divorced when I was five years old, so I’ve always been in between houses. I grew up in downtown Manhattan and then also in Suffern, in upstate New York. I’ve always been traveling back and forth in cars, with a night or weekend bag. I recently figured out that I love being in transit—on a train or in cars, there’s so much I can see out the window. If you’re in a car with me, I’m going to take a picture of something that we’re driving by.

After my parents divorced, my dad and stepmom had a girl named Ava, and my mom and stepdad had a girl and a boy, Dakota and Cameron. Becoming an older sibling at age fourteen was one of the biggest blessings in my life, creatively and emotionally. To have younger siblings who were so confident in their expression and were just silly, running around and dancing, made me get into that zone as well. It was such a lighthearted time. It kept me grounded in what actually mattered to me. And when I was fourteen, I found photography, and I started taking pictures of my siblings.

Acheampong: What would you photograph them doing in those days? Would you capture them candidly playing, or would you pose them for the camera?

Bobb-Willis: It was a bit of everything. We would do fashion shoots. I’d also just document them throughout the day. I would take pictures of them running, in motion. I would take pictures of them at night, with flash. I was very scared at the time to ask other people to do a photoshoot. So my siblings were my first subjects. They just let me do my thing. They always knew me as a photographer, since they were born, so they never questioned it.

Acheampong: Did the fear and shyness you felt when you were younger push you into creating your own world in your art, or was it something you had to overcome in order to really feel confident in yourself as an artist?

Bobb-Willis: It was definitely something I had to overcome, but the shyness still shows up in my work. It’s a part of who I am. I still pretty much keep to myself. When I’m shooting, I can either show parts of myself that are loud or I can hide in my work. When I first started photographing, I asked myself, How can I take a picture of myself without being in the photo? And also: How can I show all the parts of myself? That was the premise. Photography showed up in my life at the right time, for sure.

Acheampong: How were you first introduced to photography?

Bobb-Willis: I moved to South Carolina when I was fourteen. My mom got remarried, and I was just thrown off course. I didn’t have the right resources at the time to go through a big change like that. And I didn’t feel very comfortable in the school I was in. It was a private college-prep school. I’m exaggerating, but I was one of four Black kids, if you know what I mean.

Arielle Bobb-Willis: Keep the Kid Alive

36.00

$36.00Add to cart

Acheampong: I believe it.

Bobb-Willis: I lived in Aiken, South Carolina, which is a horse town and a retirement community. There’s not a lot going on. I felt really isolated from a New York experience that I could have had. I developed anxiety and a really deep depression, and it lasted for about five years until I got professional help.

During the first week of school, I had to enroll in an elective, and I was a new kid, so they just threw me into this digital-imaging course. I had a little black point-and-shoot, one of the square ones, nothing with a lens or anything. I learned about the basics of photography in that elective and was introduced to Photoshop. I became obsessed. I loved that class because for that part of the day, it was like I was in a trance. We got to restore old photographs. If you’ve ever used Photoshop, you know that editing can sometimes be a slow process, and that kept me very present with what I was doing and what was in front of me, and not thinking about what I did in first period or what

I had to do next week. I think depression robs you of being present and seeing the beauty around you.

I was working with a digital camera for the course, but my history teacher said his wife didn’t want her camera anymore and gave it to me. It was a film camera, a Nikon N80. I went home, and I took my first roll of film.

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Portland, Oregon, 2023

Acheampong: What did you photograph?

Bobb-Willis: It was at sunset, so my bedroom had a golden-hour vibe. I lifted one of my shoes up in the air, and I took a picture of it. I had a mannequin in my room, and I took a picture of that too. I remember going to CVS and being really excited to get the developed film back.

There had been an orange tint in my room. The orange became more orangey with film. I had black shoes on, and on the film, the edges around my black shoe were soft and melted into the orange. That was the moment where I was like, Oh my God, oh my God. This is so cool. This is so sick. This is what I want to do forever.

At the time, I was always in my room, and there was usually a very gray, dreary kind of feeling in my room. But seeing those photos of these bright oranges and reds and yellows and blacks made my room into something better. I realized that photography can make a whole world—your own world. It turned my room into something that it wasn’t, and it looked like a place of peace, brighter and better than what I was feeling at that time.

Acheampong: That feels so connected to your current work: it’s not easy to geographically place a lot of your images, because the subjects almost seem like they could be existing in a fantasy world that you’ve created for yourself. How do you choose locations for these shoots?

Bobb-Willis: I told you about how I’ve been traveling in cars from my mom to my dad my whole life, and how I’m always looking out of car windows, and just observing all the time.

I think that constantly observing is just in my DNA in a way, and it shapes the way I pick locations. I’m not really looking to shoot in front of the Empire State Building, or the Golden Gate Bridge, or other landmarks that show that I’m in a specific place. Instead I might say, Oh, the light is shining on this pink wall at 2 p.m. I’m going to go shoot there at 2 p.m. Or, There’s a shadow from a tree right here on this red building. The paint is being chipped off and has an interesting texture. Oh, I’ll shoot there.

Acheampong: The fact that you spend much of your time looking out of car windows makes sense, because I feel like so many of the background details are ones that you would see when you’re passing through a place—like a nondescript alleyway that you would glance down, and then briefly wonder what it might hold. And in the same way that your locations are fairly nondescript, the clothes that your models wear tend to look unbranded and anonymous, or not quite like something you would find in a store.

I love styling but not styling in the sense of “I need designer clothes to do this shoot.” I’ve changed shirts into skirts and cut out holes into the shirt. Or I’ll stretch a shirt out so that I can put two people in it. I put a lot of people in shirts backward and inside out. A skirt doesn’t have to be a skirt just because it’s presented that way. It could be whatever you want it to be. I love styling in that sense, where it’s play, it’s fun, it’s exploration.

Photography is, and will always be, a daily practice of falling in love with as many things as I can.

Acheampong: That definitely stood out to me about your work—you’re not precious about the clothes. As you said, sometimes you’ll stretch a fabric to its limits, or the fabrics will be wrinkled or bunched up. Or, simply, a bra strap will hang off a model’s shoulder. At the same time though, the bright colors and flamboyance of the outfits seem to contradict the casualness with which they’re being worn. Could you speak to how you see luxury and fashion coexisting in your photography? Is the malleability of a piece of clothing what you find most luxurious about it?

Bobb-Willis: Oh, that’s a good question. The luxury for me is to be able to create the clothing myself, create the clothing that I want to see or need in the moment. It started out with me having twenty dollars and being like, Okay. What can I do with twenty dollars? I think that as an artist, having limitations can make you more creative. With designer things, I feel like sometimes I can’t do as much. It comes already finished in a sense, you know?

Acheampong: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

Which is fun. It’s fun to work with people and to shoot beautiful things that someone else has created and took the time to cut into. But it’s also fun and luxurious to create things that I want on the spot and improvise.

Acheampong: After New York and Aiken, where did you live next?

Bobb-Willis: From eighteen to twenty-three, I was in New Orleans. I was still heavily depressed at that time, but New Orleans was the place where I found community. And I felt like I was in a place where I could create things. It was where I got my depression under control, actually.

I had a freedom there that I didn’t have when I was in South Carolina. I was free to be with my own thoughts and not the thoughts of my peers, or my family, or anything like that. I was mostly by myself, which felt really nice and different than in South Carolina. It was isolating, I guess. But being alone can feel good in certain places, you know? It helps you see clearly about what you need for yourself and what kind of people you want to be around.

Acheampong: New Orleans, I think, is a city where even when you are alone, you’re surrounded by so much vibrancy and life on the streets. I imagine you were always in a community with others even if you were in your own thoughts?

Bobb-Willis: Yeah. Totally. I love the duality of New Orleans. There’s a duality to the entire city: The houses are very colorful, but they’re also kind of falling apart. There’s a tension in the air, and the air is very heavy.

I was working at a retail store and just shooting for retail here and there. Then, I found a group of people who I started to create zines and other things with. Then, one day, on my way home from my retail job, I got hit by a car. This was in 2016. I was riding my bike on St. Charles Avenue, and . . . the car just came. It was a hit-and-run. I tore their side-view mirror off with my left shoulder and left arm. Moments before the impact, I thought to myself, Oh, I get twenty-one years. I was like, Okay. That’s fine . . . I’m okay with that—and then I got hit. There was nothing I could do at that point, and I felt this calming acceptance come over me.

Acheampong: I’m amazed that your thoughts even cohered in that moment.

Bobb-Willis: Me too. I didn’t know that happened. You know, in movies, how they say that things slow down a bit? It’s weird, but they actually did slow down. Then I got hit, and when I opened my eyes, I thought, Oh, I’m still here. Okay.

Acheampong: How long did it take you to recover from that?

Bobb-Willis: I tore a ligament in my shoulder, and it’s still a problem. The left side of my body is still a problem in some ways.

A couple months before getting hit, the first love of my life had suddenly broken up with me, which was also debilitating to me. I was also bedridden for six weeks, and I couldn’t work my retail job. I was just able to really sit with myself during that time. I started to think, You don’t have a job. You don’t have a boyfriend. You don’t have any responsibilities, really. So, what do you want? And I saw her—older Arielle—very clearly, and I thought, I’m going to take pictures, and I’m not going to hold back. Once I got a little bit better, I quit my job, and then I started to shoot the things that are in the book.

Acheampong: So the origin story for this work began on the heels of a near-death experience.

Bobb-Willis: Yes. The car accident, the breakup . . . It’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me.

Acheampong: Wow. After that series of events, what differences did you notice in the type of work you most wanted to make?

Bobb-Willis: It made me more of a brave person. I feel like I create like a child because I do not give a fuck. I mean, I don’t care what anyone thinks of me while I’m creating. I do it in the streets and outside, and people are honking and pointing or screaming out of their cars.

New Orleans is a city that’s dense with culture, and so, living there as I recovered, there was so much for me to work with. And I told myself, I’m just going to do what I want to do because it can all be gone tomorrow.

Acheampong: You spoke earlier about New Orleans being a place that juxtaposes its colors and brightness and all of the partying with a darker tinge that can be found in a lot of corners of the city. And you yourself had a very contradictory experience in which your worst, near-death moments were paired with a real moment of joyful discovery. I want to talk about how a similar tension appears in your photos. I think that one of the hallmarks of your images is the fact that there’s a playfulness in some of your subjects’ poses and clothing, but there is definitely also a cloudiness. I noticed that, in almost every image, people’s faces are somehow obscured—either covered in shadow or covered in paint or a mask or just turned away, to the side. Could you say a little bit about that gesture and why it recurs in so much of your work?

Bobb-Willis: My reasons for that change over time. But I think it’s partially inspired by the paintings that I love. Like in Milton Avery’s work: I feel like that world is where I want to live. I wish we all looked like that. I wish we all didn’t have to have our faces determine if we’re valuable or not. Like why are some people considered more “photographable” than others? In the grand scheme of the photo/fashion industry, who gets to determine that?

I’m more inspired by painters than artists of any other medium, and I think about the painters whose work surrounded me growing up: Jacob Lawrence, Basquiat, and William H. Johnson, and, from New Orleans, Sister Gertrude Morgan. When you’re painting, you can make someone’s head a foot. You can have someone’s leg go around their body, like, six times. Do you know what I mean?

Acheampong: Mm-hmm.

Bobb-Willis: You could have someone floating in midair in a painting. There are unlimited things you could do with the body in paintings, and I love that freedom. I’m trying to put that freedom into my photos, and I’m trying to gently push my subjects to do things that are maybe a little bit out of their comfort zone. I don’t want to do it too far, but just gently push people to maybe try things that are not a pose you would do on the regular day-to-day.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Acheampong: I think that relates to the playfulness that is so core to your work in general as well as to your first foray into making photographs: with your very first subjects, your younger siblings, you began by capturing them at play. And I’d like to ask you the same question that you’ve been asking the other artists who have contributed to this book: How do you keep your inner child alive—in your photography and in your day-to-day life?

Bobb-Willis: Photography is how I keep my inner child alive. Photography has taught me to fall in love with life. I love finding unexpected rainbows, and sunshine and a beautiful green park and kids’ chalk drawings on the sidewalk and melted ice cream and butterflies and flowers and Black girls with bright-blue braids and sweet graffiti poetry! I keep my inner child alive by taking pictures of my every day. I’m always finding things that I’m so in love with. Some you’ll see collected in the booklet in this book. I’m so grateful that photography has given me that. It’s given me that gift to always see beauty wherever I go. It’s made me a lighter, brighter individual.

Since I was a child, and even when I was in my teens, I never really spoke up. Photography has taught me how to communicate what I need from the people around me. It’s taught me that there’s so much power in my imagination. It taught me how to trust in my taste, my opinions, and myself. It’s given me true self-love, and that I can stand firm in who I am. My journey with photography has been a very emotional, world-expanding experience. There’s just so much all the time to see, and take pictures of, and fall in love with. Photography is, and will always be, a daily practice of falling in love with as many things as I can.

This interview originally appeared in Arielle Bobb-Willis: Keep the Kid Alive (Aperture, 2024).