Interviews

How Awol Erizku Is Building a Visual Multiverse

In this interview from his Aperture monograph, the artist speaks about his entry into photography and the collective legacies of Blackness.

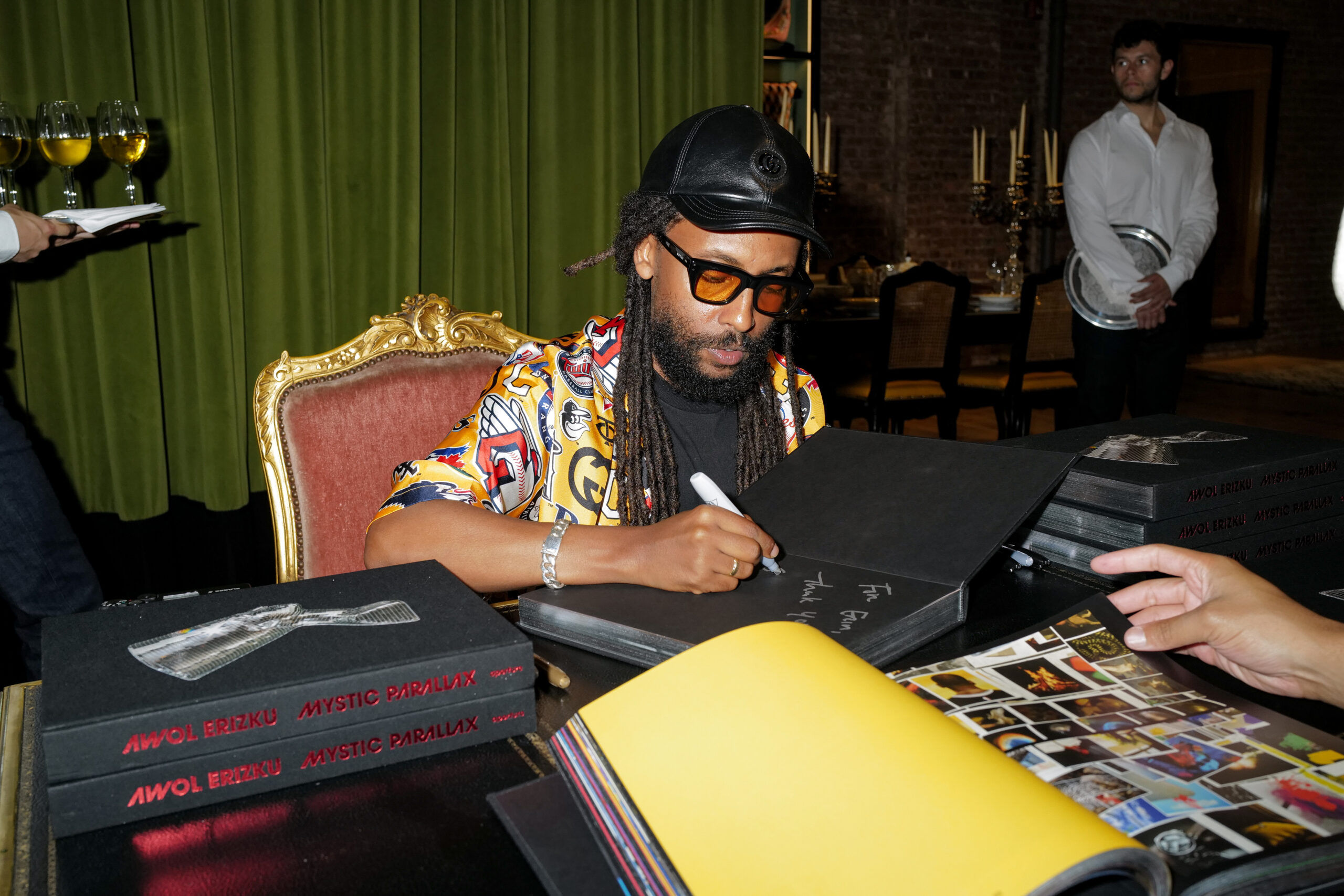

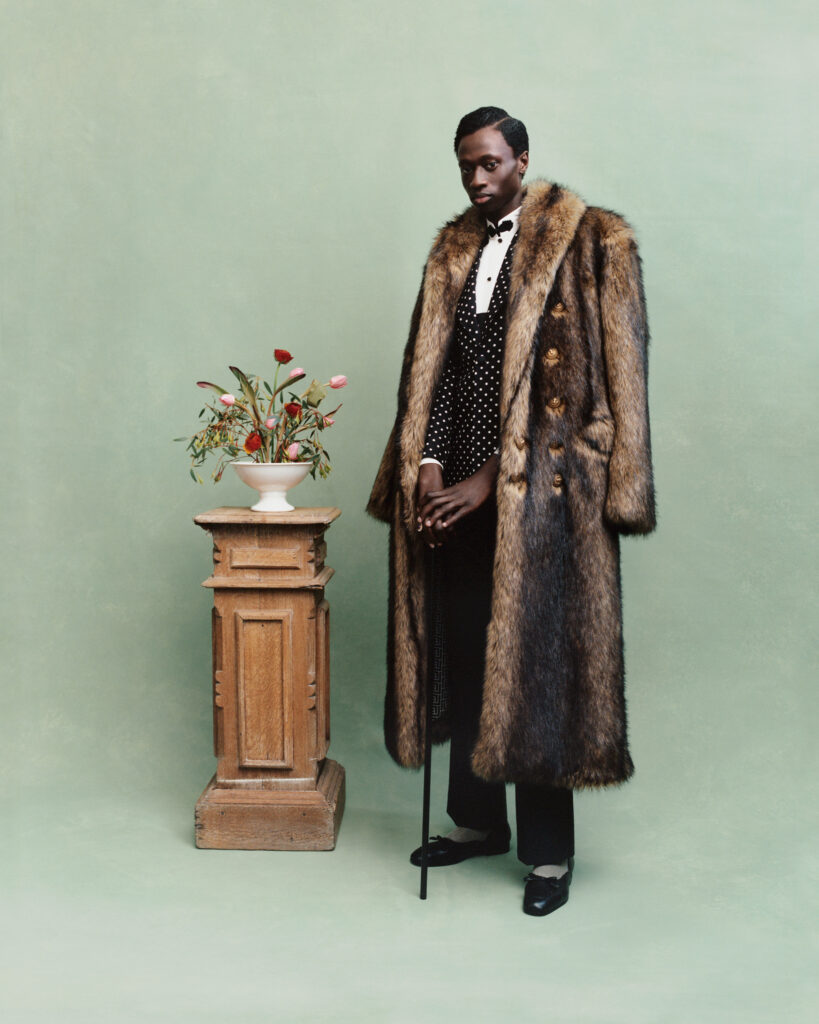

Awol Erizku’s vision is as expansive as it is restless. His work across photography, film, sculpture, and installation reimagines African American and African visual culture, from hip-hop vernacular to Nefertiti, while nodding to traditions of spirituality and Surrealism along the way. Aperture has worked with Erizku for close to a decade. In 2016, his striking portrait of a young woman at an Afropunk festival, pictured against a luminous orange backdrop, graced the cover of Aperture’s “Vision & Justice” issue. In 2023, Aperture published Mystic Parallax, a book blending Erizku’s studio practice with his work as an in-demand editorial photographer, including his conceptual portraits of cultural icons such as Solange, Amanda Gorman, and Michael B. Jordan. “It’s important for me to create confident, powerful, downright regal images of Black people,” Erizku has said of his distinctive approach to portraiture. For Mystic Parallax, the curator Antwaun Sargent interviewed Erizku about the motifs that cycle through his art, remixing the Western canon, and his fluid approach to media.

Antwaun Sargent: This book presents you as an image maker, and not necessarily in one particular box. The sculpture, the painting, the photography, the installation. When I first met you, though, all those years ago, the label that folks were associating with you was “photographer.” What first motivated you to make images in this world?

Awol Erizku: I guess you could say it was a meandering path getting to photography. If we go back to high school, I was doing medical illustration, which is very technical. Senior year, I began making figurative paintings. Sophomore to junior year of college is when I really started making serious, conceptual photographs.

Even though I didn’t have the lexicon to discuss or define what a picture such as Girl with a Bamboo Earring (2009) meant for me at that time, I was thinking about it conceptually. When I considered the Old Masters, I thought: What’s the most direct visual format I can employ to make something that can subvert the Western canon?

Of course, at the time, and this is still true, the most pressing question for me was Black representation. This image became a way of talking about Blackness and dimensions of Blackness without focusing on my subjects in their own environments and the conditions of where they came from. Instead, it’s about their style, aesthetic, and the celebration of their uniqueness.

Access to social media platforms such as Tumblr then enabled a kind of leveling. Where it once took many years to be exposed to a work of art by way of exhibitions and printed matter, now the same number of people, if not more, could see a new work of art in a fraction of the time and share it worldwide. For me, the conceptual aspect of that has always been the Google search suggestion for when someone looks up Vermeer’s Girl with a . . . and stumbles upon Girl with a Bamboo Earring.

Sargent: That image is part of a larger body of work, of friends, family members, and strangers, that you recast using art-historical references. The subject in Girl with a Bamboo Earring is, famously, your sister. Can you talk about that body of work in relationship to, at that point in your career, how you were reconsidering the art-historical with the camera?

Erizku: In a lot of ways, this work was very much a reaction to the kind of conditioning and schooling that I was getting at the time. I was using that image as a way to propose a new ideal and to combat the popular visual culture that seldom celebrated the type of subjects I was drawn to from the streets and the neighborhoods I spent most of my time in. It’s about being indoctrinated and being told a specific version of history and art. Then having to accept the fact that you don’t really see yourself in that, and yet you have to memorize and recite these names, places, and ideologies.

I remember watching the film Girl with a Pearl Earring in a class in high school and thinking, This has nothing to do with the things that I see every day. I literally would leave the projects to go to school, and on my way, I might get stopped by somebody trying to rob me.

Sargent: You went to an art high school, right?

Erizku: Yes. I come from this really harsh neighborhood in the South Bronx, and then I’d go to Manhattan. Your experience is one reality, and then you’re told, This is how the world is. Let’s not forget, this is pre–social media.

Sargent: And before a racial reckoning in the art world, or even caring about Black people.

Erizku: Exactly. I was using the camera, or just art in general, as a way to ask: Is this really the only way we can see the world, or can beauty be seen in other things? For me, the reason why Girl with a Bamboo Earring is poignant is that, regardless of the subject being my sister, I think it’s about an undeniable beauty that isn’t Eurocentric.

Sargent: We’re in this moment in photography where the conceptual and the commercial are often blended. But from the very beginning of your practice, you’ve always sought to do that, by showing images in different contexts, whether in a museum or a magazine, or, when starting out, on Tumblr.

Erizku: I always consider what my images can be. Sometimes sculptures end up becoming images when they are photographed. Or sometimes images are presented as sculptures. For me, and you know this very well, the studio is my universe. Whatever makes it into my studio enters the ongoing dialogue within my universe.

In the case of the traditional photographs, I’ve always considered them photographs of us. When I say “us,” I mean the diaspora. Melanated people around the world. One of the things that I learned to do early on was understand my position in whatever space—art space, commercial space—and try to make the best work from that position. If I pick up a camera to photograph anybody, anything, it has to start with the purest intention. It has to be done so that, ultimately, it is another offering into a continuum, into the constellation of vast imagery of who we are. It’s never just about my preoccupation with art history. It has so much to do with what I want to see evolve in our culture. I think that kind of thinking also leads me back to music, which, again, coming from the Bronx, you have to respect hip hop. When I started making associations and images that were inspired by lyrics or subcultures, they came from a place of honoring and understanding the true essence of it all, and making a solid effort to elevate it.

I always think about my work as a constellation, and a new piece is just another star within the universe.

Sargent: You have this association with music from jazz to hip hop, which is an enduring association with Black sonic progression in the culture—

Erizku: Improvisation.

Sargent: Exactly. You have Nipsey Hussle, DMX, Jesse Boykins III, and Beyoncé as these different icons in your work. But then there’s also your use of color, the use of gold and how that is very hip hop. But it’s also something very distinct in the parts of African culture that you engage with in your practice. It’s not just the people who are photographed, but the way you’re using color to think about links between Black cultures.

Erizku: Absolutely. Color plays many roles. Purple is commonly known as a regal color. I try to depict my subjects as highly dignified versions of themselves. I ask them to project their idealized selves. Whenever I make a portrait of someone, I make a point to let that person know they should think of themselves as highly as they possibly can. I often say, “We are here because we’re making this image of you, and we want this moment to last.” If I’m making an image of someone, whether they are a celebrity or not, it’s almost always a collaboration. I think I leave enough room for that person to bring their own idiosyncrasies into the image.

Sargent: Why is it important that it’s a collaborative image?

Erizku: I know this may sound cheesy, but when you take someone’s photo, you’re really capturing their soul. It’s not something that I go into every session thinking about, but when I find myself there, when I’m locked in with any subject, there’s an immaculate synergy that flows. I can only tease out those moments through collaboration. It can never happen with me just directing poses.

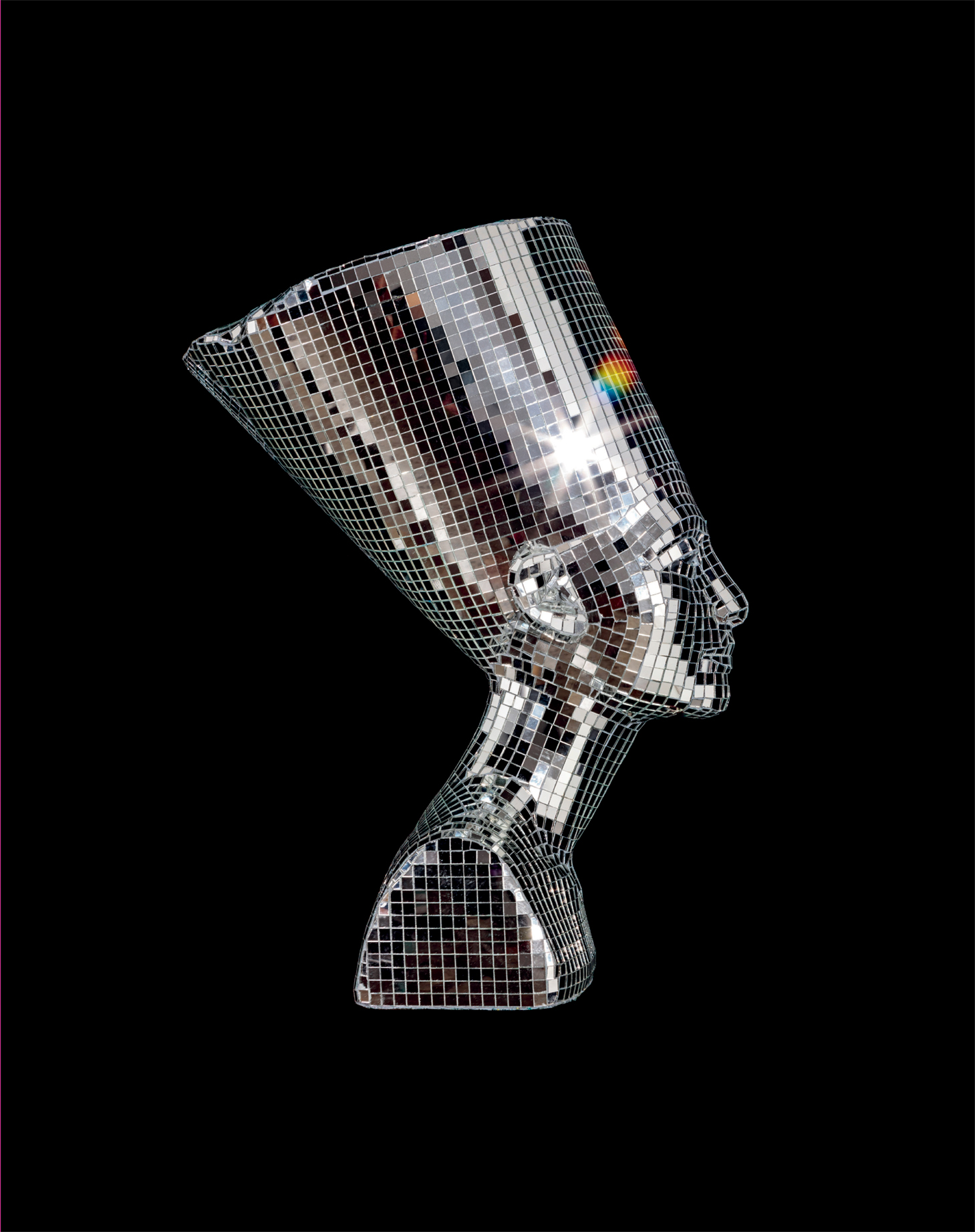

Awol Erizku, Malcolm X Freestyle (Pharaoh’s Dance), 2019–20

Sargent: Along with the portraits, you also make many still lifes. What led you to that genre?

Erizku: A lot of it is just being in LA. The change of scene from New York, from leaving the hustle and bustle and settling into a vast city that I didn’t know too well. LA is not the easiest place to meet people organically. I focused more on painting and sculpture when I arrived. The objects I collected for sculptures became subjects for my light tests. That turned into an aesthetic investigation of things, whether photographing a rock on wheels or different kinds of flowers and plants under different lights.

Sargent: Within those still lifes, two dominant motifs are the African mask and the Nefertiti bust. You place these objects in relationship to flowers or various other objects, including guns, records, and books. There are endless juxtapositions. Those two symbols also travel throughout your practice, from photography to sculpture to installation.

Erizku: The African mask has this really rich, complicated, troubled history, particularly in the Americas and Europe. Man Ray, Picasso, and Modigliani used African masks. These are not people who come from the places where those masks are from. To my knowledge, they don’t have blood affinity to these places.

I started working with African masks during my first year at Yale and continued to work with them for several years before I hit a spiritual firewall. As a practitioner of the Muslim faith, I could not uphold or invest any spiritual value in objects made for commercial consumption (I bought them on the street in New York).

This was a blessing in disguise. It allowed me freedom to make the only move that I felt was missing in the African mask dialogue, which was burning them as a way to make something I had never seen before. For me, that was a very symbolic moment, both personally and politically. A premonition of where I felt the world was headed. These works were made from the end of 2018 through the pandemic in 2020. It was a tumultuous time. Trump was in office. I was on the verge of becoming a father for the first time. The world was equally exciting and extremely terrifying.

Also around the same time, there was a surge of artists using African masks. Whether in sculpture or photography, artists were making mediocre mask-related works. What was missing in all of this noise? For me, it was how people dealt with African masks in a post-spiritual aspect.

Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax

75.00

$75.00Add to cart

Sargent: With Nefertiti, you use this symbol in numerous ways: as a white bust painted black, within still lifes, as a light box, as a disco ball, fabricated in both silver and gold. How did you come to Nefertiti?

Erizku: It has to do with the notion of reclamation. I grew up being reminded of what and who I looked like as a young boy. I would often hear that I reminded people of someone who is Egyptian or Ethiopian or Eritrean, even Cuban at times (only in the Bronx). These little side comments, often meant to be offensive, stuck with me. As an adult, I realized identity itself is a kind of conceptual material to make work from. My identity shifted as I found myself in different parts of the world. When I began growing my locs, eight or nine years ago, that also complicated things. People used my features to categorize who I am and where they thought I was from.

To come back to Nefertiti, I felt she had an aura that I gravitated toward. Yes, she’s an Egyptian figure, but what does that actually mean today? The original bust of her resides in a Berlin museum. Hollywood movies often depict Egyptians from ancient times with Eurocentric features and mannerisms. I find the whitewashing of African sovereign states and their representations troubling. I want people to think of her and other important Black African figures as Black first, before anything else. Her image across the diaspora is supreme. For me, it’s a direct way of signaling Black influence, a quick way of anchoring our collective efforts and countering the continued whitewashing of her identity.

Courtesy Gagosian

Sargent: The Nefertiti disco ball in the Memories of a Lost Sphinx exhibition that we did in 2022 spun and reflected light; it was almost like a cosmic presence. It became a universe. It became a portal. You’ve talked a lot about the use of surrealist notions to create your own universe.

Erizku: I find a lot more surrealism in real life than in what the imagination could conjure. Life is very strange, and I take a lot of cues from personal, day-to-day shit. I try to reflect and mirror what I see in the world around me.

Sargent: There’s also a Pan-African element to your work, with the use of the tricolor flag.

Erizku: Nefertiti and the Pan-African flag are kind of interchangeable to me. They offer a way for us to see ourselves in imagery, in sculpture, in fashion, and universally in a work of art. When you see Black art in non-Black spaces, it radically changes the dynamic in the space. I remember visiting so many European museums and not seeing any Black art and feeling left out, thinking that they’re missing out on a great deal of history. So, my inclination and my practice is to make things that not only evoke a certain kind of feeling but unapologetically dominate the spaces they occupy.

Sargent: How do you think about location in your image making?

Erizku: When I’m on location, I’m very specific about incorporating the surrounding environment as much as possible. I think, again, it goes back to the idea of creating a universe. Black beings in an environment, being themselves, being cool, calm, and collected. They’re dignified; they’re exercising a high form of regality; they are seldom timid. They’re owning the space.

Sargent: There’s also something about nature—you often bring the natural world into the studio. We see Black figures interacting with nature, showing a command of nature, as with Tessa Thompson and the falcon, or Amanda Gorman and the caged bird.

Erizku: I mean, you said it. For me, it’s important that we show these figures in command. It is a literal and a metaphorical gesture. Kids like myself grew up looking at newsstands and collecting magazines, which informed our understanding of the world. Life imitates art. I think of my younger self running around bookshops and grabbing any new magazine that had the most exciting cover on it, just so I could hold and revisit that fantasy.

Sargent: There is also a sense of spirituality that is evoked in some of your work. There’s the wax, the burning candle, the incense, which create a mood. Can you talk about the esoteric in relationship to your art-making practice?

Erizku: When I mention the esoteric on a very surface level, I just mean the things that, if you’re of this culture, I don’t have to explain to you. I don’t have to spoon-feed it to you. It’s already in you, you grew up with it, you know what it isn’t as much as you know what it is.

I work within a continuum of the Black imagination. It’s not just one thing. It’s spirituality, it’s hip hop, it’s things from our collective legacies. I think even within the still lifes there is a bit of a self-portrait. I quote Marcel Duchamp, from a documentary I saw, “The esoteric can’t be expressed in words.”

Sargent: In the juxtapositions of objects, there’s also this notion of time passing. When you say “continuum,” it means not a fixed place but rather a movement. The Nefertiti disco ball is also about time. It’s about the rotation. It’s a globe, right?

Erizku: Most certainly.

Sargent: A planet, a universe.

Erizku: A Black universe.

Sargent: Another thing I love about your practice, and have throughout the decade that we’ve known each other, is how you approach photographing the Black body.

Erizku: I know it’s not very present in a didactic or obvious way, but I do think about Robert Mapplethorpe. I think about all these non-Black artists, photographers, image makers, whoever, who have dealt with the Black body, who fashioned and exploited it for their use and consumption.

I do think about that aspect of photographic history.

Instead of saying, I’m going to deliberately go against that, I’m just trying to create what I imagine is a universal centrality when it comes to the Black body. How do we make Blackness as universal as, let’s just say, European or Western aesthetics? When I was in school, the white female body was a kind of neutral resting place for the Western gaze. When we rest our eyes on the white female body in a painting or a photograph, we almost don’t even consider it as a white female body. We’re just like, This is the female body. I was like, Well, why can’t we see Black figures and Black bodies in the same way? And why do we have to make this sort of grand gesture to make it so? Why do I have to reference Manet or Caravaggio, or any of the Old Masters, in order for you to understand that the Black body could be just as sensual and just as integral to how we perceive ourselves in images and other forms of representation?

Sargent: In the Reclining Venus (2013) series made in Ethiopia, there is a direct art-historical reference to painters like Manet. But then there are these other realities to consider, like the exploitation of Black bodies, and that image makers have enacted violence on the Black body. There is both a history of stereotypes and subjugation, and a great history of freedom.

Erizku: I would show the models reproductions of Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Grande Odalisque (1814), paintings that I was interrogating at the time, so that they understood the context. There was also a person, who fully understood the project and who connected me with the subjects. The idea was to make a body of work that challenged antiquated notions, like how the eye is trained to accept the reclining white body as a kind of neutral in art history. For me, the repetition of these images, with the same positioning, as well as the fact that they’re in these similar interiors, was a way to hit that same note over and over again.

Sargent: You also make paintings yourself. Why did you turn to painting? Did it evolve from your wider image making practice?

Erizku: I never turned to painting as much as came back around to it. During a hiatus from painting, I began experimenting with cameras, moving and still. A lot of my photographs are meticulous, from the sets, lighting, and post-production. But with my paintings, I come to them without any preconceived notion other than the energy I feel when I’m making marks on a surface. The paintings are looser than my photographs; I’m free to go in any direction when I’m painting.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Sargent: You often incorporate basketball rims or representations of other objects, like the hand-with-rose image. This creates a tension between the language of painting and the language we often ascribe to photo-based image making.

Erizku: That tension is what I’m after, a marriage between the picture plane, or surface, and a three-dimensional object. I’ve always gravitated toward marks on surfaces in the real world, be it the floor of a train or a tagged wall of a building. My interest in adding additional objects to my paintings is to load the surface with rich signifiers and make new things from perpetual aesthetic accumulation.

Sargent: What is interesting about your thinking about painting in relationship to photography, or even sculpture, is this idea that you’re an image maker across different media.

Erizku: Whatever medium I am using, the work communicates a set of ideas in a direct manner. With my straight photographs, my interests are solely in the photographic image. But when I make a sculpture, I have to think about and contend with how these pieces will live as images on social media and other digital platforms. Reproductions of the work still function as an image, a very lasting image. It’s not just by using a camera that I’m making an image. How you set up a work of art in a space and have people interact with it, that too is part of image making.

Sargent: And within those spaces, we see a range, young Black people, old Black people, so many references, going all the way back to ancient history. The project maps out a universe.

Erizku: I love that. That’s actually the best possible way of explaining what I do. I always think about my work as a constellation, and a new piece is just another star within the universe. This goes back to the idea of a continuum of the Black imagination. When it’s my turn, as an image maker, a visual griot, as I understand myself to be, it is up to me to redefine a concept, give it a new tone, a new look, a new visual form.

This interview originally appeared in Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (Aperture/The Momentary, 2023).