All photographs courtesy the artist

Essays

How Tommy Kha’s Mischievous Portraits Challenge the Idea of Belonging

The artist's visual jokes, out-of-place expressions, and even a cutout of his own face mark his presence in the world—and tell a story about Asian American identity.

Tommy Kha told me about a moment, not too long ago, when he was photographing his mother and she asked him: Why is art always so sad?

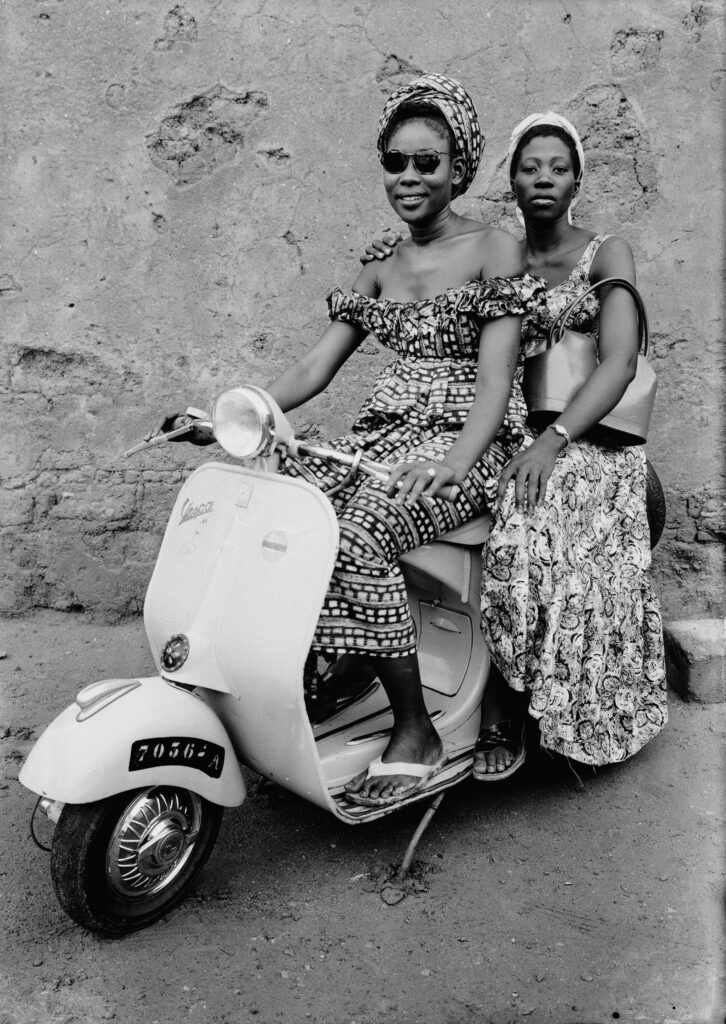

She fled Vietnam in the eighties, raising Tommy and his sister in Memphis. When they were children, the history that had delivered their family to America was passed down in fragments and gestures. It was a story that was never told. Rather, it was carried through expressions or habits, with a tendency toward conversational dead ends, and in the chasm between shouting and silence. In her closet, Tommy’s mother had kept photographs from when she was younger, some from Vietnam but most taken in Ontario, her first home in North America, in the eighties. Washed-out snapshots of friends gathered around plates of food or birthday cakes, self-portraits on a pier, at the beach, with enormous stuffed animals, or perched in a tree. These pictures weren’t art, she was suggesting to Tommy, just moments from a past she never discussed.

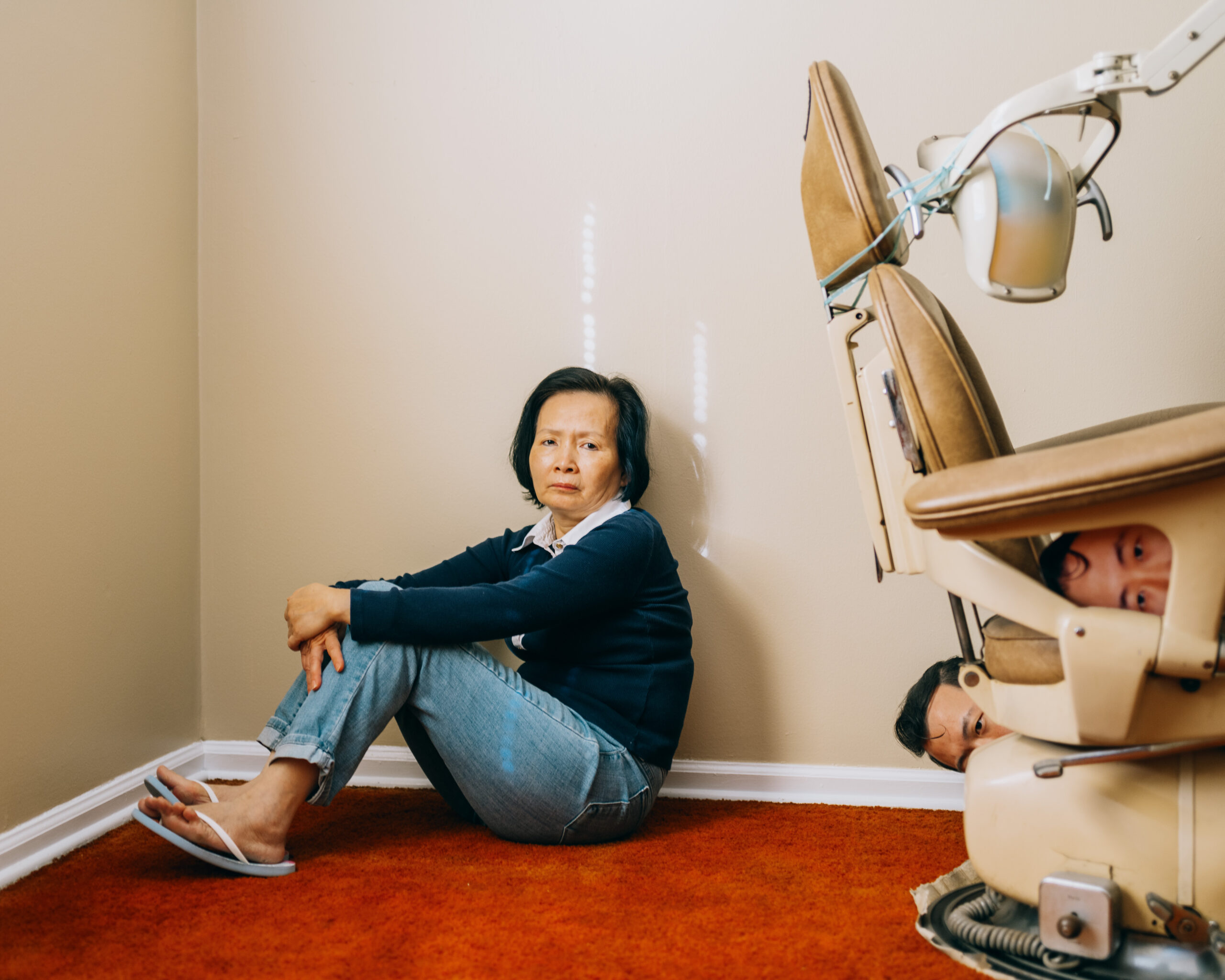

As Tommy pursued his own path as an artist, he and his mother settled into a routine. She would make him food, and then he would take pictures of her, usually inside her home or in her backyard, making these overfamiliar settings feel mysterious and alien. She frequently looks troubled in these images; maybe she is just annoyed. People need to smile more, she told him.

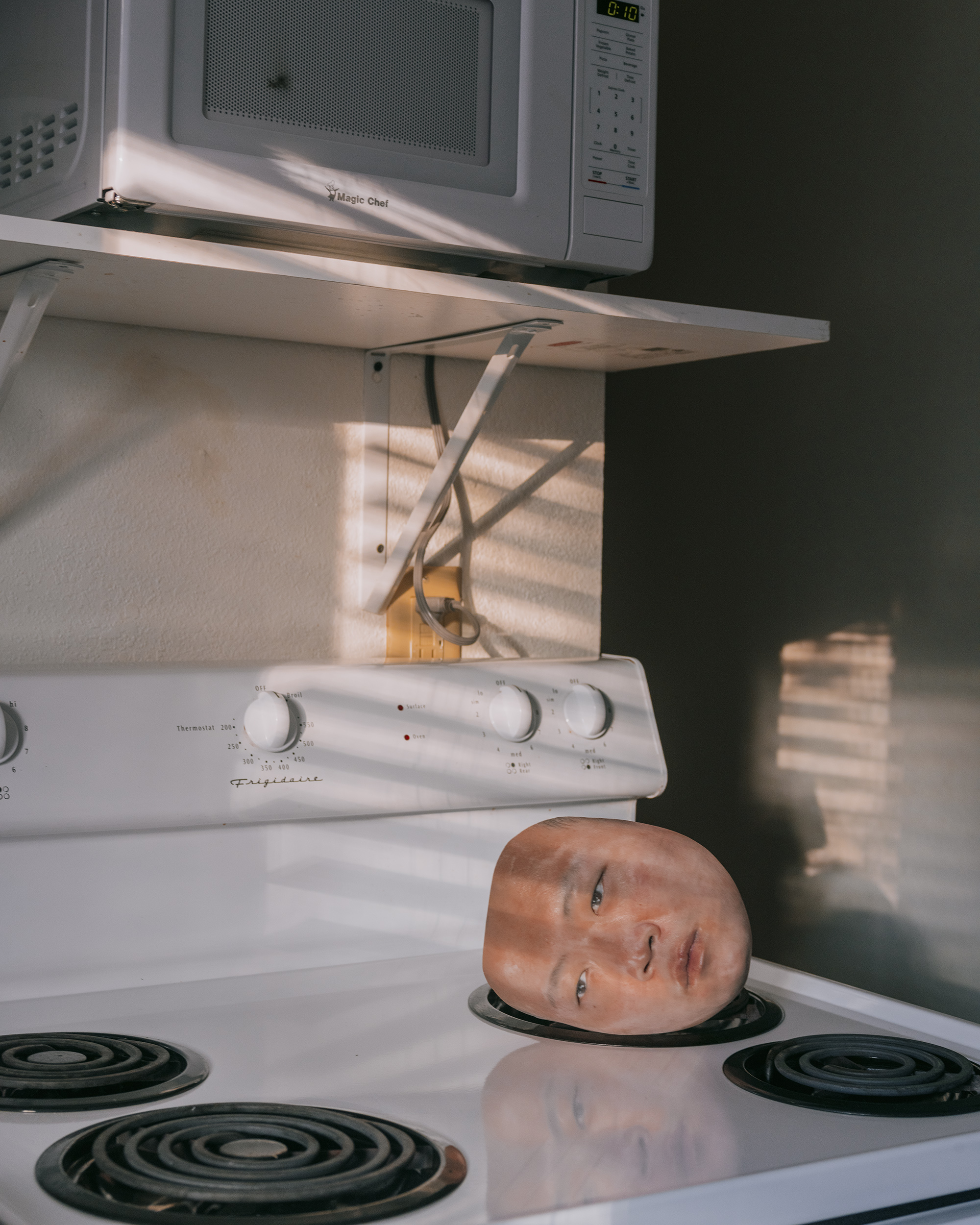

I don’t find Tommy’s work sad at all. A life-size cutout of Elvis Presley with Tommy’s face slapped over the iconic singer’s? This is hilarious, mischievous, surreal stuff. That’s not where he’s supposed to be, which is part of how his art seizes you. The compositions are gorgeous and meticulous, with Kha masterfully capturing these soothing, garish auras in the naturally occurring colors of our world. But there’s often something a bit off. A flourish—visual jokes, out-of-place expressions, a glimpse of a cutout of his own face—that marks his presence.

(Re) Assemblies, 2023

150.00

$150.00Add to cart

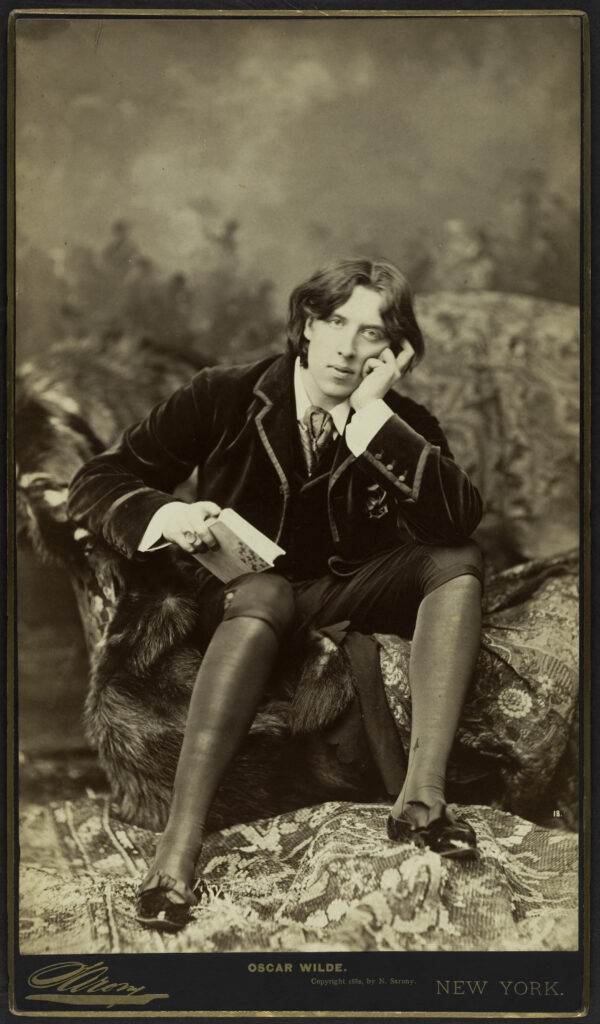

When Tommy began taking photographs, he was inspired by the work of Nan Goldin to document his friends, many of them performers and musicians, as they made their racket around town. To better pull focus for his self portraits, he toted around an Elvis cutout. But over time, inspired in part by Claude Cahun, Reka Reisinger, and Tseng Kwong Chi, he began incorporating the cutouts themselves, producing a different kind of self-representation. On one hand, these self-portraits dramatize his sense of dislocation—of not belonging, maybe even invading, or judging, these scenes of pure Americana. They suggest an insolubility, the impossibility of assimilating, whether into a nation or an everyday background. He experimented with printing his face on pillows or puzzles so that he was, quite literally, fragmented. But all of this felt playful too. His family and friends cradled his cutout, played dress-up with a reproduction of his face, as if poking fun at its overly serious, some might say inscrutable, expression.

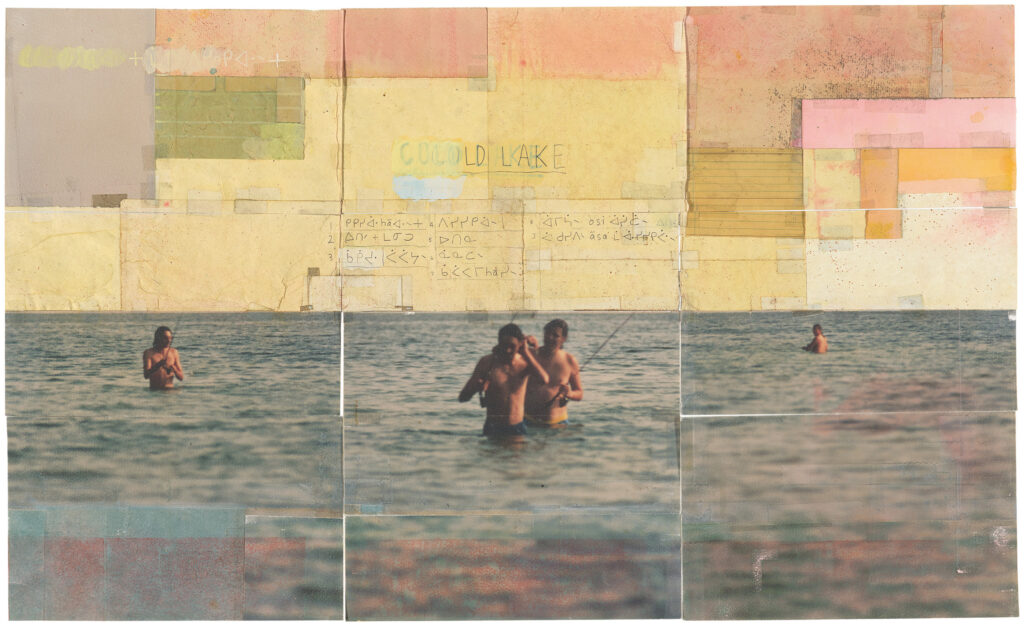

Most of the photos in this book were taken by Tommy. Interspersed are faded snap-shots from a photo album his mother passed onto him and his sister a few years ago with little explanation or context. The pictures are full of friends and acquaintances from her early years in Ontario, most of whom the children do not know. Some of the photos are reproduced here in full; others have been cut to lift figures from backgrounds and are arranged into collages, leaving only jagged, island-like clusters of new immigrants against a blank expanse.

The children of immigrants learn of the world first through the oft-limited horizons of those around us. We don’t see ourselves in the culture, so we learn how to breach America by studying our families, our parents, and nearby elders. Photography was the only form of art they participated in, only it wasn’t art, it was just something to do. It was a ritual, a place to put their memories, fleeting visions of the new world to mail back to the old one, if anyone was still there. There were minor details of self-presentation, like a cherished piece of clothing or a carefree smile, perhaps the only gestures of self-fashioning that felt comfortable in those days. The fact that Tommy’s mother had kept this album all these years communicates enough.

And you realize: this isn’t just Tommy’s book, and the photos from the eighties aren’t just there to provide context about his world. These snapshots sit effortlessly alongside his austere pictures of Memphis and his carefully staged family portraits. Together, they offer us a sense of collaborative possibility, a wondrous back-and-forth between present and future, a collaboration that goes unremarked upon, since there are certain aspects of the past that we never talk about. Instead, the images in this book speak to one another in glances, smiles, echoes. What we inherit isn’t just language but the angle you hold your head when you listen.

There are photos of Tommy’s mother in the corner of her father’s home dental office, where he practiced in private for family and friends after not being able to establish his license in the US. A cutout of Tommy’s face is nestled in the chair. He doesn’t belong there. Then again, the room itself indexes an entire history of not belonging. Elsewhere, mother and son lie next to one another in a living room, gazing in different directions. Her face is weary, perhaps because that’s what she thinks she’s supposed to do with her face. She’s playacting. But sometimes, she looks back at the camera, at Tommy, and she understands that they are there at the same time, sharing a moment, even if neither of them can put to words what that is.

These pictures aren’t sad; they’re hopeful. They luxuriate in the ongoingness of family and history. Nothing is resolved. But what draws us forward are moments of reckoning, as generations take turns telling a shared story. A fragment will never join with the whole. It is a new whole.

This essay originally appeared in Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (Aperture, 2023).