Interviews

Melina Matsoukas Creates Space for Black Stories in Hollywood and Beyond

Solange Knowles interviews the director about her visionary career spanning fashion, photography, music, and film.

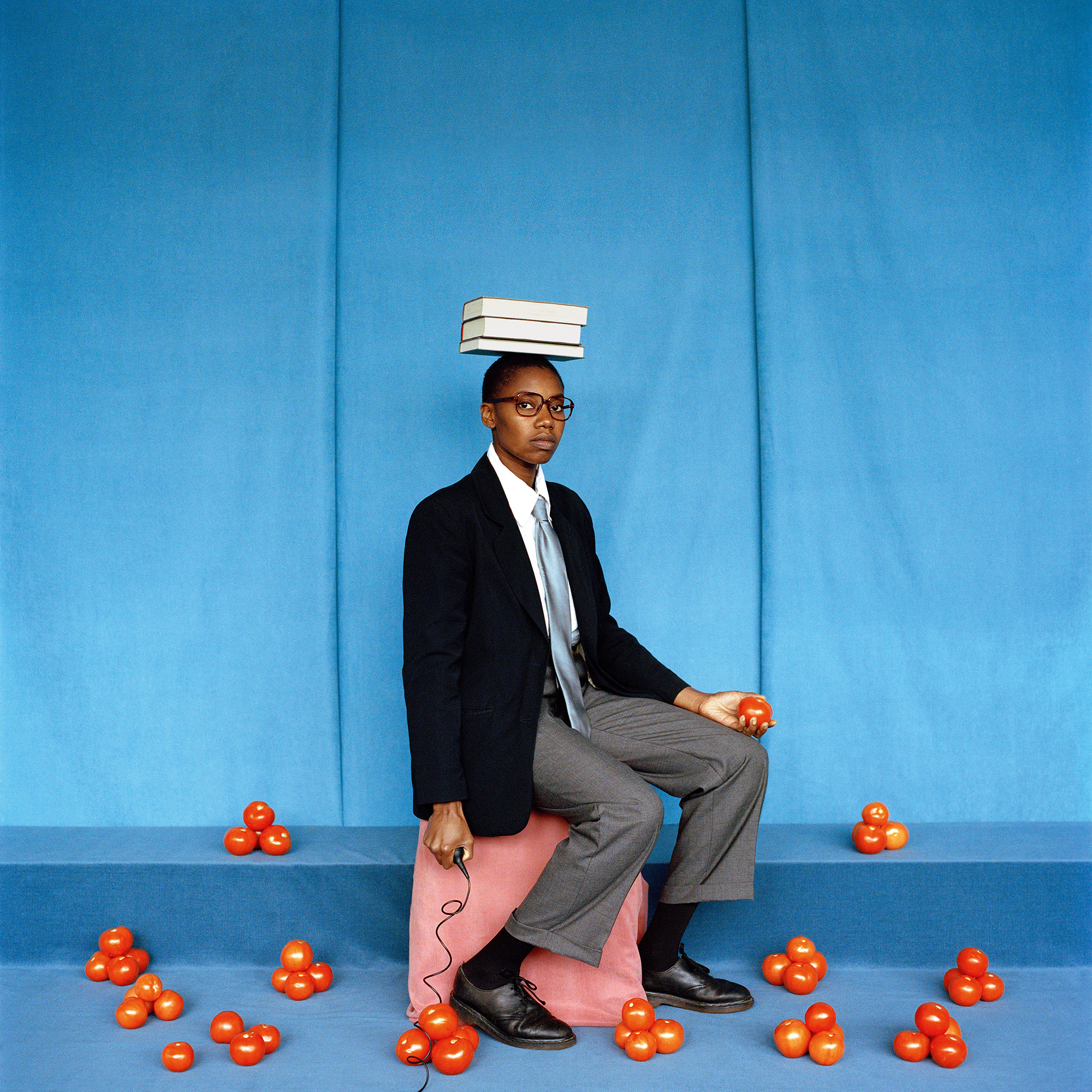

Photograph by Alexander Saladrigas for Aperture

Melina Matsoukas has made a lasting mark on visual culture as the director of unforgettable music videos—among them Rihanna’s “We Found Love” and Beyoncé’s “Formation”—and the 2019 feature film Queen & Slim, which bends the romance outlaw genre into an utterly contemporary meditation on police brutality and Black love.

In some ways, though, it feels like Matsoukas is just getting started. The Los Angeles–based polymath is currently developing a flurry of passion projects (the only projects she does), among them adapting a legendary female mobster’s life for the screen and documenting her own experience as a new mother. On top of everything, Matsoukas also runs De La Revolución, a bicoastal collective of photographers and directors that she founded in 2021 as an alternative to exploitative models of inclusion in the creative sphere.

Solange Knowles, the singer-songwriter, recently sat down with Matsoukas for the “Barbara Walters treatment,” interviewing her friend and collaborator about her expansive image making across the fields of photography, music, television, commercials, and film.

Courtesy the artist

Solange Knowles: One of the powerful things about an image is that it lives far beyond us, forever. At what age did you understand the gravity of image making?

Melina Matsoukas: I was raised by freedom fighters. My parents were part of a socialist movement called the Progressive Labor Party, and I was raised to create change and incite dialogue, to challenge the status quo and how people think. I always felt like I had this purpose to do these things and honor my family and the people that empowered me. I just didn’t know what the tool or medium would be to do that.

In high school, I started dabbling in photography. My father was an amateur photographer, and he introduced me to the power of the lens and the idea of documentation and what that can do as a tool in the revolution. And then, when I got to college—I went to New York University—I really started understanding the reach and the scope and the conversation and the story you could create with the photograph, and understanding the power of filmmaking to reach the world and to give voice to the unheard, to document communities that we don’t necessarily see all the time, and use that power to unify people. That felt like my purpose.

Knowles: I love this origin story. I didn’t know your father was an amateur photographer.

Matsoukas: He’s going through all his slides now, thousands of slides of our family and friends, and just our lives. It’s so beautiful to have that archive.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

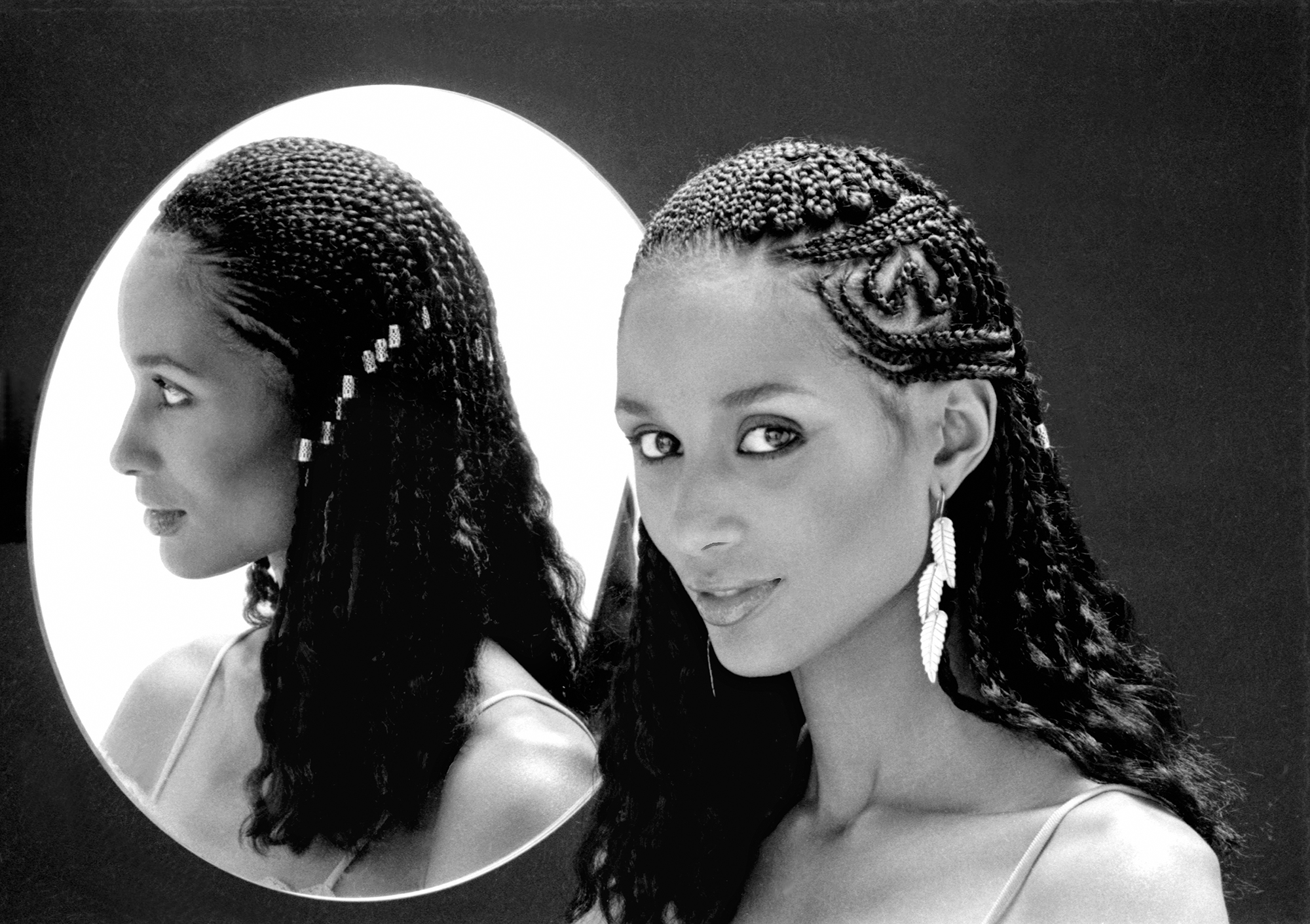

Knowles: I think a lot about the photographs that you took in Cuba in 2001 and how personal and intimate and special they are, and the gravity they hold. Although, obviously, your style has evolved and changed, I still see the loving, tender, and attentive gaze of how you see Black women—and have always seen Black women—in those images, celebrating their strength and vulnerability, but also allowing them to just be. I wonder how your adult self sees those images.

Matsoukas: NYU had a summer exchange program where I went to Cuba and studied photography for a summer. That was actually my first time in Cuba, my first time returning to my mother’s homeland. It was an incredible experience to be able to take that camera and have the courage to photograph people—and learning how to do that and thinking of Ming Smith and Gordon Parks and Anthony Barboza, all these people who have documented our history. I remember being shy, and not wanting to essentially steal these images of people without asking permission. But then, it’s a hard dance to play. You ask permission and then people start posing, and that’s not necessarily what you want. Anyway, I was able to really hone the skill of being a street photographer there.

At the same time, I had this other side of me, and I still do, where I like fashion and celebrating Black women and bodies, and embracing our sexuality and our beauty. One of my main goals in life is to change the idea of what traditional beauty looks like in our culture. I was also able to photograph some of my friends and the people that were on the trip with me, and other Cuban women. I did a series of nudes, I remember.

Knowles: And some pregnant women.

Matsoukas: Yes, that was a friend of mine. When I look back at those pictures, I feel like, Oh, they’re very amateur. It was definitely part of my journey to understand the technicality of how to take a photograph. But there’s a lot of themes in that work that have continued and evolved through my career, which seems pretty evident, in terms of how I look at Black women and try to celebrate them and honor the role that they’ve played in my life and my artistry.

Still from Melina Matsoukas’s music video for Solange Knowles’s “Losing You,” 2012

Courtesy the artist

Knowles: When you talk about the song and dance between the gaze and the lens, and also finding that trust with people to capture them authentically, I often think about our first time—well, second time—working together, which was the video for “Losing You,” and being in South Africa, and us wanting to enter the continent with as much sensitivity as possible. When you pull out the camera, you feel definitely a little shy or hesitant in some ways. But as soon as the cameras came out, the sapeurs came to life. I know from being on the other side of the lens, sometimes the photographer can have all of the technical skills in the world, the best lighting, the best set design, or can capture on an expert level—but if the synergy is not there and I don’t feel comfortable or safe, then my jaw is tight and it’s clenched, and you can see that in the image. Are there any specific skill sets you bring to the experience to have people put their guard down and feel safe with you to capture them at their most vulnerable and authentic?

Matsoukas: I think the key to that, and to my success, is humility and respect for the subject. My job has always been to tell someone else’s story. It’s never to tell my story. I’m trying to document and bring out somebody else’s influences and feelings and values and inspirations. So it never begins or ends with me.

Knowles: I think that you are one of the best commercial directors of our generation, and I know it’s really difficult to find a way to maintain a sense of authenticity and integrity and even spirituality when working with commerce and the idea of selling something. It’s something that I actually have thought a lot about in my practice, because in our creative industries, people sneer or frown upon commercial work, despite the gravity to storytelling and the incredible ways that you can use commercial work to tell stories. That’s something that I’m fascinated by.

What is your approach to commercial work? And how do you choose the projects that you wish to be a part of?

Matsoukas: I was so influenced by pop culture, with MTV and music videos and, honestly, with commercials. I always wanted to start on music videos. In my younger years, I definitely did things just to pay bills. But at one point in my career, I was like, I can’t do this anymore; it’s not worth enough to work on things I’m not passionate about.

So in my commercial work, I try to find brands or stories that I believe in. And with commercial work, the reach is so much greater because of the money behind it. I find that it’s actually a great way to create change. When we talk about changing what the standard of beauty is, that’s created by commercials—commercial advertising and what you see on television and all of that. So in order to be a part of that dialogue, you have to actually enter that dialogue.

I try not to get too product heavy. I hate shooting products, so that’s kind of a deal breaker for me. But I love to tell stories. I made a Levi’s commercial two years ago, in Jamaica. I’m part Jamaican, and they sent me a story of how Levi’s in the ’70s made its way to Jamaica, and these people made it their own, and it was kind of the staple of reggae and dancehall, and the role that denim played in that culture. I felt such closeness to that subject matter and that era and time and that visual language.

Courtesy Getty Images

Courtesy the artist

Knowles: I want to use that as a segue into De La Revolución and talk about how you have transitioned not only as a businesswoman and an agency but as a mentor to emerging directors and photographers, and what that day-to-day looks like for you, how that’s changed the way that you approach your own work. Tell us more about that.

Matsoukas: So I did a film called Queen & Slim. I fought really hard to bring in four different photographers to shoot alongside me as I was making that film, to interpret the film in a way that was different than what I was shooting. One of them was Andre Wagner. He’s an amazing, primarily street, photographer. I call him our generation’s Gordon Parks. I also invited the incredibly talented photographer Lelanie Foster, who was there the whole time. She’s my cousin, too, so that helps. She was able to photograph the actors and the behind-the-scenes, and have access in a way that I thought was just so powerful. I brought Awol Erizku there a couple times to take objects from the film that symbolize the story and create still lifes around them.

I loved the idea of this collective coming together to tell one story. I thought back to the Kamoinge Workshop, the Black collective in the ’60s. Anthony Barboza was part of it, Ming Smith, Shawn Walker, Daniel Dawson, Jimmie Mannas, and many others.

In my journey, I’ve gone from photography to music videos, to commercials, to narrative and film, to TV—and they’re all very separated. There’s not a lot of crossover in terms of the people you work with, and the crew. They like to keep it so segregated. I hate that, because obviously there’s incredible crossover. So being a part of this collective during my film inspired me to create a space that actually helps guide directors and photographers in their goals and what they want to achieve.

De La Revolución was born of a time when people were starting to exploit Black artists, and feeling like, Oh, I want to have this person on my roster because they’re Black, and I want them to shoot Black people, but I have no understanding of the culture, I don’t care about who this is profiting, where it’s going, I just want to check a box. I wanted to provide a safe space that felt more like community, a collective of support and empowerment. So that’s why I started De La Revolución over one banner. My mother is from Cuba and was a child of the revolution, so I feel like I’m a child of the revolution in ways that I’ve inherited from her.

I always felt like I had this purpose to do these things and honor my family and the people that empowered me.

Knowles: I’m so proud of you and what you’ve done with. . . would you call it an agency? A studio?

Matsoukas: It’s all of that. Agency, studio, production company, collective, whatever you want it to be. That’s family. That’s who we are.

Knowles: It’s been incredible to watch it unfold. Thinking about Queen & Slim, and the world that you created not only with just the film but with the music and with the style and with the rollout and the stills, what have you learned from that process of world making and the importance of the space that surrounds the film just as much as the film itself?

Matsoukas: That was an incredibly challenging journey, creating the film. I didn’t realize it, because I had never done a film, that the way that you market it is just as important to the success of the film as the film itself. So for me, it actually was a way that I was able to take what I felt my skill set was and bring it all together. Obviously, I started in music, so the music’s going to be really important. The collaborative nature of filmmaking is what I truly enjoy and flourish in, and is one of the reasons I became a filmmaker. So to have all these different, incredible artists involved in the making, but also the rollout, of the film was really important, and it felt important to stay true to the messaging behind the film.

We wanted to make sure our community had access to the film first. So we had a screening at the Underground Museum in LA and the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York before it was out, and we focused on Black publications and journalists first before we brought it to the broader audience.

Knowles: I’m curious how at this stage, after your success with Insecure and The Changeling, you decide on other projects you want to pursue.

Matsoukas: I’m working on a lot of things. I’m developing a film based on Marlon James’s novel A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014), which is a story that takes place in ’70s Jamaica and moves to ’80s New York—two periods that are very important to me in my life and my artistry. I’m working on a film on Stephanie St. Clair, who was this West Indian woman who ran Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance and protected it from white mobsters. It’s a gangster flick about this incredible woman who has been erased from history. And I’m working on a TV show on Jack Johnson, who was the first Black heavyweight boxing champion—he’s from Galveston, your place—with HBO. That’s a series. There’s a bunch of other projects that are in the works that I hope will come to fruition in the next couple of years. I’m also working on raising my baby and documenting that journey of motherhood and life.

Knowles: I love seeing you as a mother to Charli, and I’m very excited to see how that will impact and influence your work in your lens as well—because I know that it will.

I had a few other questions. My favorite moment, among my top three Melina moments, was Master of None’s “Thanksgiving” episode. The fact that you created such iconography with one episode.

Matsoukas: I never really wanted to do episodic work because I like to create the world from inception. But Lena Waithe is a very persistent person, and she really wanted me to direct this episode of Master of None, which was a bottle episode about her character coming out as a lesbian to her mother, played by Angela Bassett. The story is told through several Thanksgivings, from childhood to adulthood. Like I say with everybody, “Send me the script or the song or whatever it is, and if I love it, I’ll do it.” And I fell in love with the script.

Courtesy Bettmann/Getty Images

Knowles: I love that about your work, that no matter what the medium is you have such a distinctive fingerprint. Whether it’s a music video, a film, just one episode, or a photograph, we can quickly identify that it is your language.

My last question is about the power of image making through the lens of Blackness. I feel like there was a renaissance in photography and filmmaking of Black artists, but that renaissance was through the gaze of whiteness and white validation. It’s been really interesting to see this moment in 2020 when everybody was running out to prove that they saw us and that they valued us in one way or another. What do you think the future looks like for Black artists, Black filmmakers, Black photographers in this space? And what would you like to see the world look like and evolve into?

Matsoukas: I feel like there was a renaissance when I was growing up, when there were these beautiful Black films and filmmakers that were actually kind of blacklisted afterward, like Julie Dash, Darnell Martin, Theodore Witcher, and Ernest Dickerson, to name a few. And then, yes, around 2020 or 2019, there was another renaissance for Black film, and a lot of what maybe you can call white guilt about the systemic racism within filmmaking. People were trying to move against it, which was necessary. There was a lot more space for Black stories and for those to be told by Black artists. Now a lot of people are reverting back to their racist ways, and they’re like, We never really felt differently, and now we don’t have that same pressure, and we can go back to excluding Black and people of color from this conversation, and denying access to them. Honestly, this last year has been very difficult, even for me, to get projects made that are about people of color. Many of my projects have been dropped.

I would like to see that change. I would like to see that renaissance not be a renaissance, but just be a standard. I will continue to make room for artists of color involved in filmmaking and stills and image making, period. But I think it’s also about creating that access and us being on the other side of it. I was just talking about working on a film on Stephanie St. Clair, which I had taken to a bunch of people, and nobody was interested in making it until I took it to this Black executive who was looking for a gangster film that centered on a Black woman, and she was very excited about it—and now, we’re developing that together and getting it made. A lot of other people who I have great relationships with just didn’t see the value or the idea that that has appeal to an audience—of any color. So it’s important that we’re on the other side. It’s important that we’re creating our own platforms, so that we’re creating these opportunities, and having ownership on the business and the decision-making side of things, and are on some of these boards. Until that happens, we are relinquishing the power to control our image, which is really upsetting.

Knowles: Well, we look to you.

Matsoukas: Thanks. I mean, I’m going to keep on fighting the good fight. And I will continue standing on the shoulders of many who came before me, who fought that good fight, and be influenced by them and their work, and even stand arm in arm with my fellow comrades, you being one of them, and creating Black art, and archiving it, and creating space for other Black artists, and collaborating with each other. And, also, just being able to be a cheerleader at times and showing that there’s value to our stories and our image, and we need that. That’s what feeds us. And it’s not just us. It’s the world. I feel like, especially as African Americans, our greatest commodity is our culture, and it has been shipped around the world and appropriated, and we need to regain ownership of it. And you are very much a part of that story. One of the things I love most about you is not only your art but your appreciation for our artists and our stories and the idea that we have to own them and own that history and also protect it. That’s what we need to do.

Knowles: Yes. We can end it with the words of the great NeNe Leakes: We see each other!

Matsoukas: Exactly.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”