Portfolios

Nabil Harb Seeks Mystery and Community in Central Florida

The photographer’s queer and Muslim identity gives him a distinct perspective. But, he says, “I am just as much a part of this place.”

In Polk County, Florida, Nabil Harb arranges his calendar around nights when the light turns green at dusk, how the shadows look blue in spring, or how the cicadas start to hum as the temperature reaches a hundred degrees. To live here is to know the feeling of humidity enveloping you like a duvet in July. To know in what oak hammocks you’ll find butterfly orchids blooming by May. And to count the seconds between lightning strikes and thunder in August. More than five and you’ll be fine.

Then, come September, Polk County’s creeks, rivers, and trickling branches of sweet water swell. The Green Swamp at the northern edge of the county collects the remnants of the afternoon storms before that water moves south into the Peace River as it wends its way into the Gulf of Mexico. For Harb, those veins of water that course through Polk County, alongside 554 lakes, form a map he’s been tracing all his life. With a camera, he’s started to draw his own maps, as did William Faulkner in his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, William Christenberry in Hale County, or Zora Neale Hurston next door in Orange County.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Harb left his hometown three times, living in Boston, New York, and New Haven. And like many Southerners, he returned home three times—putting stakes down between the urban sprawl of Tampa Bay and the edge of the Everglades’ headwaters just south of Orlando. “I moved back because I don’t like being that far from my concerns,” he tells me. Often, folks told him, “You’re gay. You need to move to New York,” as if he couldn’t be himself at home. “I hate that,” he says.

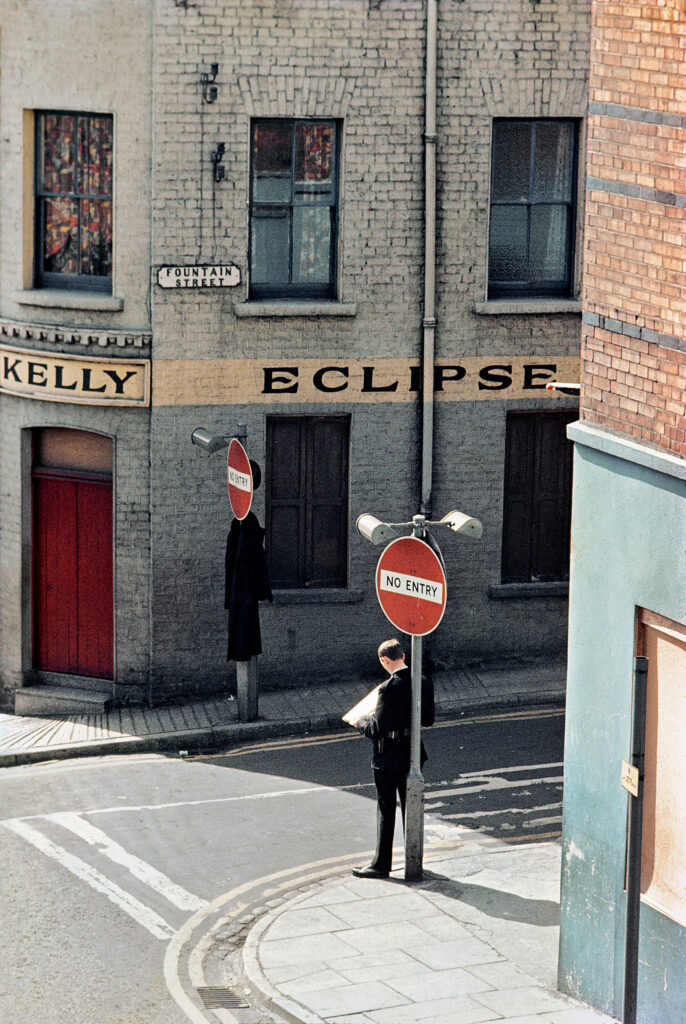

Here, everything is growing, green as ever, always. The live oaks are ancient, the sites of treaties, lynchings, and produce stands. Bends in the river call up Indigenous history, archaeology, and colonialism. In making a photograph, Harb wants you to feel how wet it is, the fog of mosquitoes, the mist rising off the ground. He wants people to better understand what rural places once were and are becoming, to know there’s good and bad in Bartow, taciturn and queer in Eloise, this and that in Frostproof. He wants others “to actually see this place, rather than the stereotypes or easy metaphors.” Beneath the headlines generated by lawmakers’ political ambitions, past the policies that target the most vulnerable and most vital minorities in Florida, Harb gives a nod to the deep well of mystery here, to a place full of people as hopeful as they are complicated.

His parents, both Palestinians who left Nazareth, made lives together in Lakeland, Florida, but for Harb, who was raised there, the roads and rivers now seem bound up in his bones. Growing up brown, Muslim, and queer in central Florida set him apart from the good ole boys, but, he states softly, “I am just as much a part of this place.”

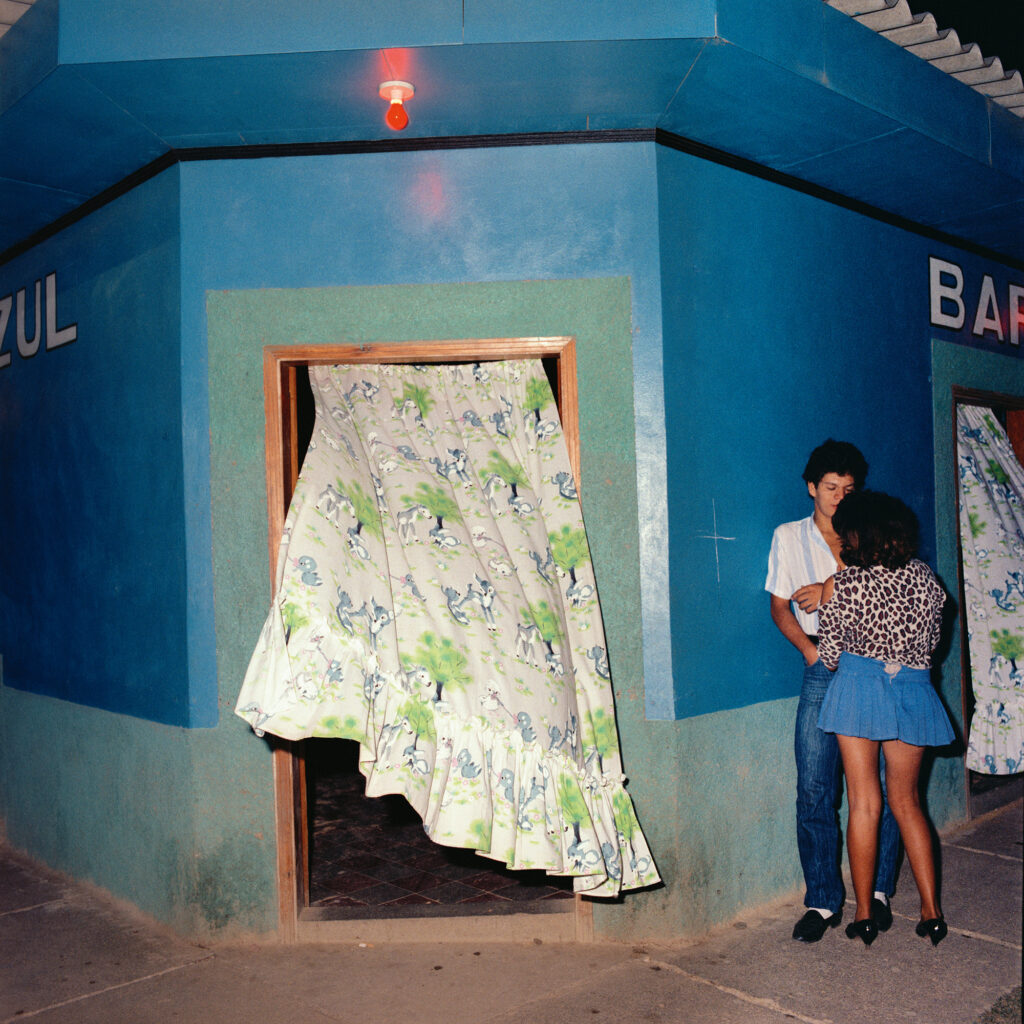

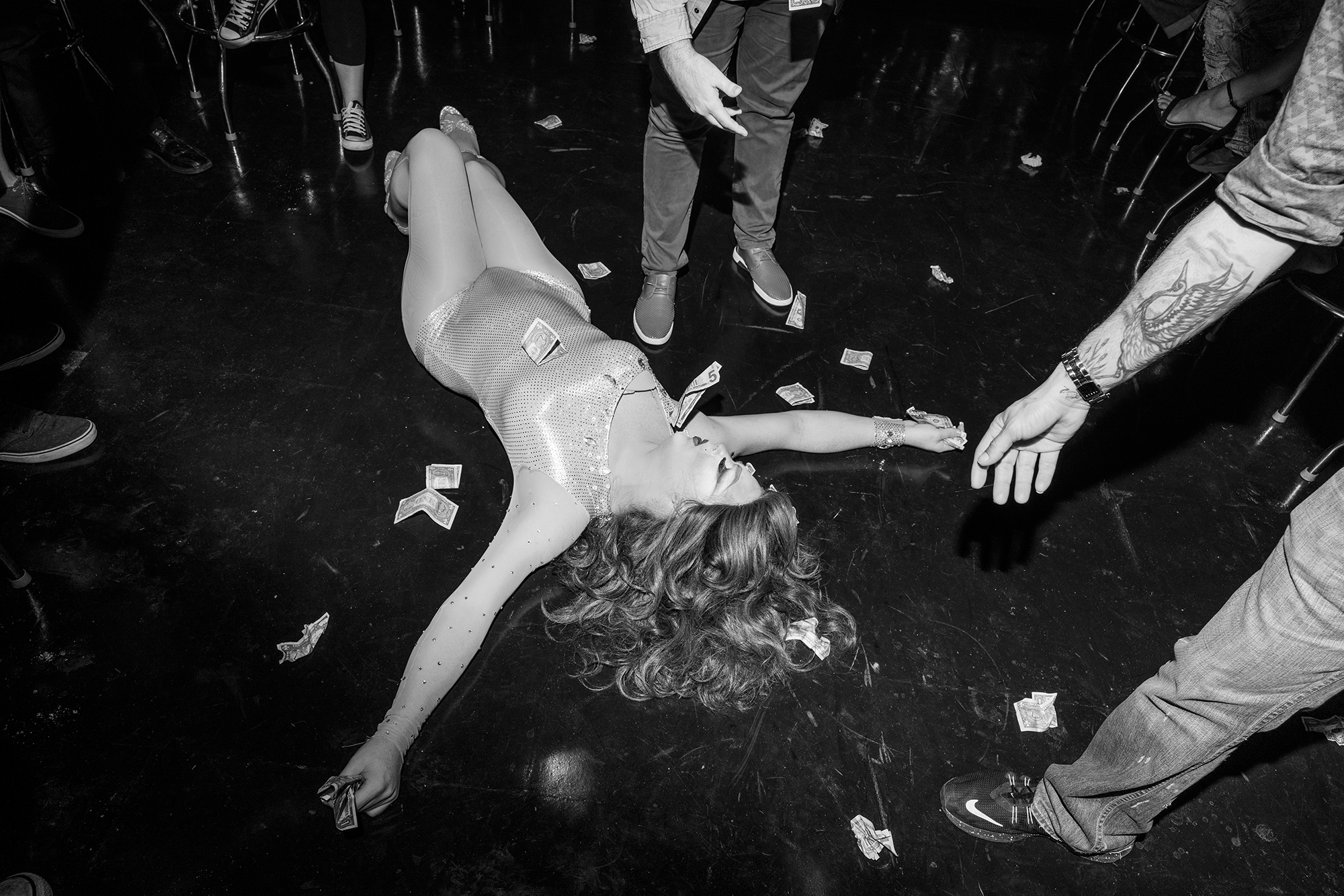

A year after the 2016 murder of forty-nine people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Harb started photographing his local gay bar in Lakeland. The work he made there was the product of questions, or a way to ask them. But as he explains, you arrive with one set of questions and leave haunted by another. These photographs, which began in earnest six years ago, have become inextricably, although not deliberately, engaged with what’s happening in Florida and throughout America today.

And as in the photographs he was making all around Polk County—say, the bugs at dusk in the Green Swamp, or his friend Clay in the cab of a truck painted in mud—he focused on the quieter details inside the bar, capturing gestures, the sense that life was being lived and celebrated. His life. Here were the queens who formed the heart of the performances, but here, also, were the people sitting at the back of the bar, his friends, the ones who lent this building and this part of America its character. As he tells me, “You should see the people.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire.”