Essays

Rediscovering Hisae Imai’s Otherworldly Vision

Once a darling of Tokyo’s avant-garde and fashion scenes in the 1960s, Imai took an unexpected turn after a tragic accident.

Never has Ophelia looked so playful. In Hisae Imai’s 1960 Ophelia, the character blooms not as Hamlet’s betrothed but as a Japanese girl, tinted blue, patiently stuffing leaves into her mouth. Her hair, curling in the wind, looks alive. Her nails are bejeweled. “Poor Ophelia,” the King laments in Shakespeare’s Hamlet when Ophelia, having gone mad, drowns in a brook, “divided from herself and her fair judgment.” In Imai’s visual renderings, this division is not within Ophelia but in how we might interpret her face and expression. Is that two dabs of glitter on her cheek, or a tear? Are we interrupting the most unthinkable time in a life—the necessary solitude of the seconds before death?

In Imai’s recasting, we do not see Ophelia’s long hair submerged into a brook—a moment of incapacity made exquisite in Sir John Everett Millais’s 1851–52 painting of the same scene. Instead, shorn and ear-length, the hair and the petals seem to be simultaneously part of her. Her expression is opaque—partly because the image is in negative—and a form of beauty confounds the viewer’s gaze. “After Ophelia went mad, she didn’t believe anything, and wasn’t afraid of death. I thought that must’ve been a lovely place,” Imai once wrote. It is this lovely calm that Imai’s many pictures of women transmit, amid the blurring of human boundaries. They appear still and absorbed elsewhere, feeling the breeze rather than confronting a gale, seemingly listening to a song we cannot hear.

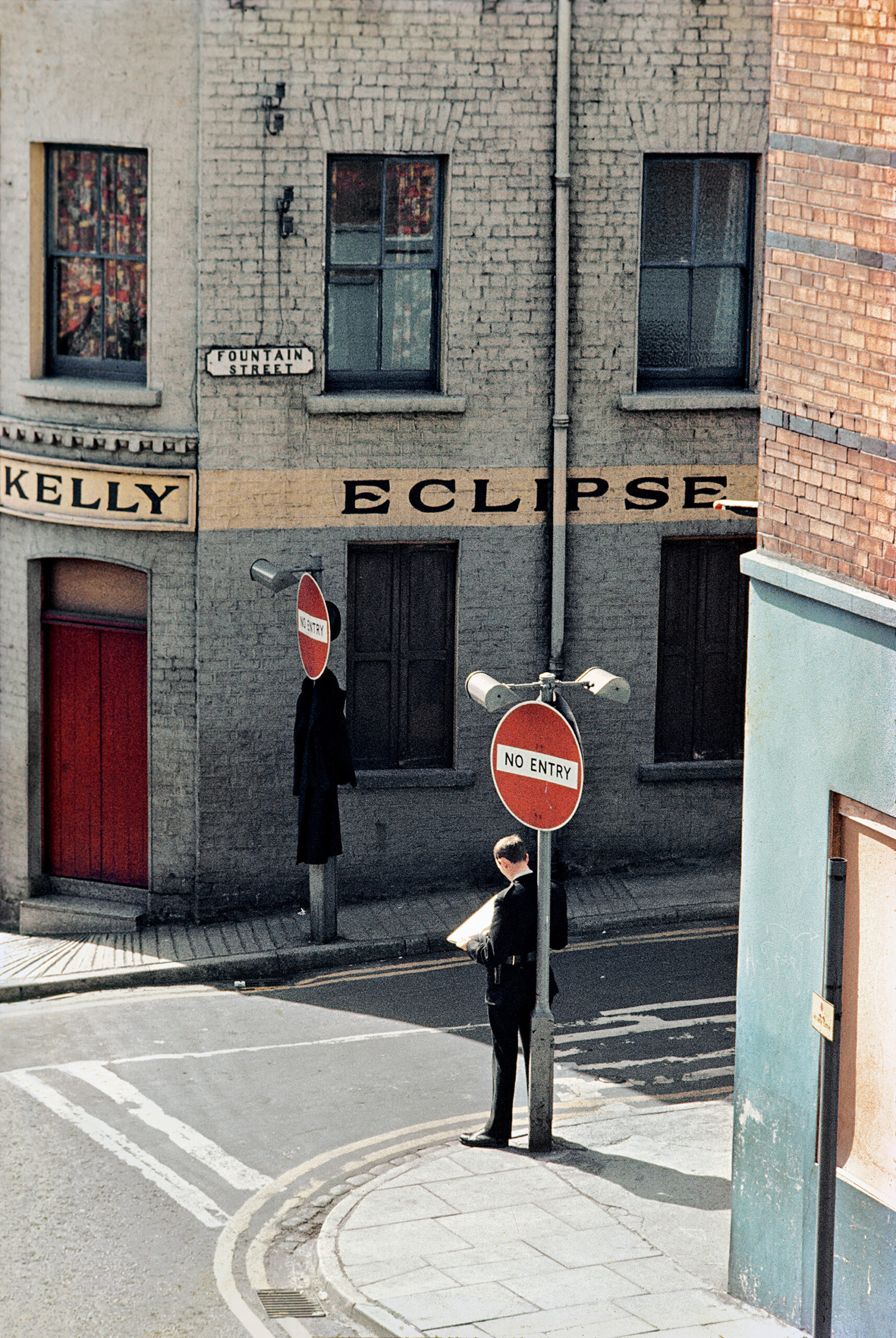

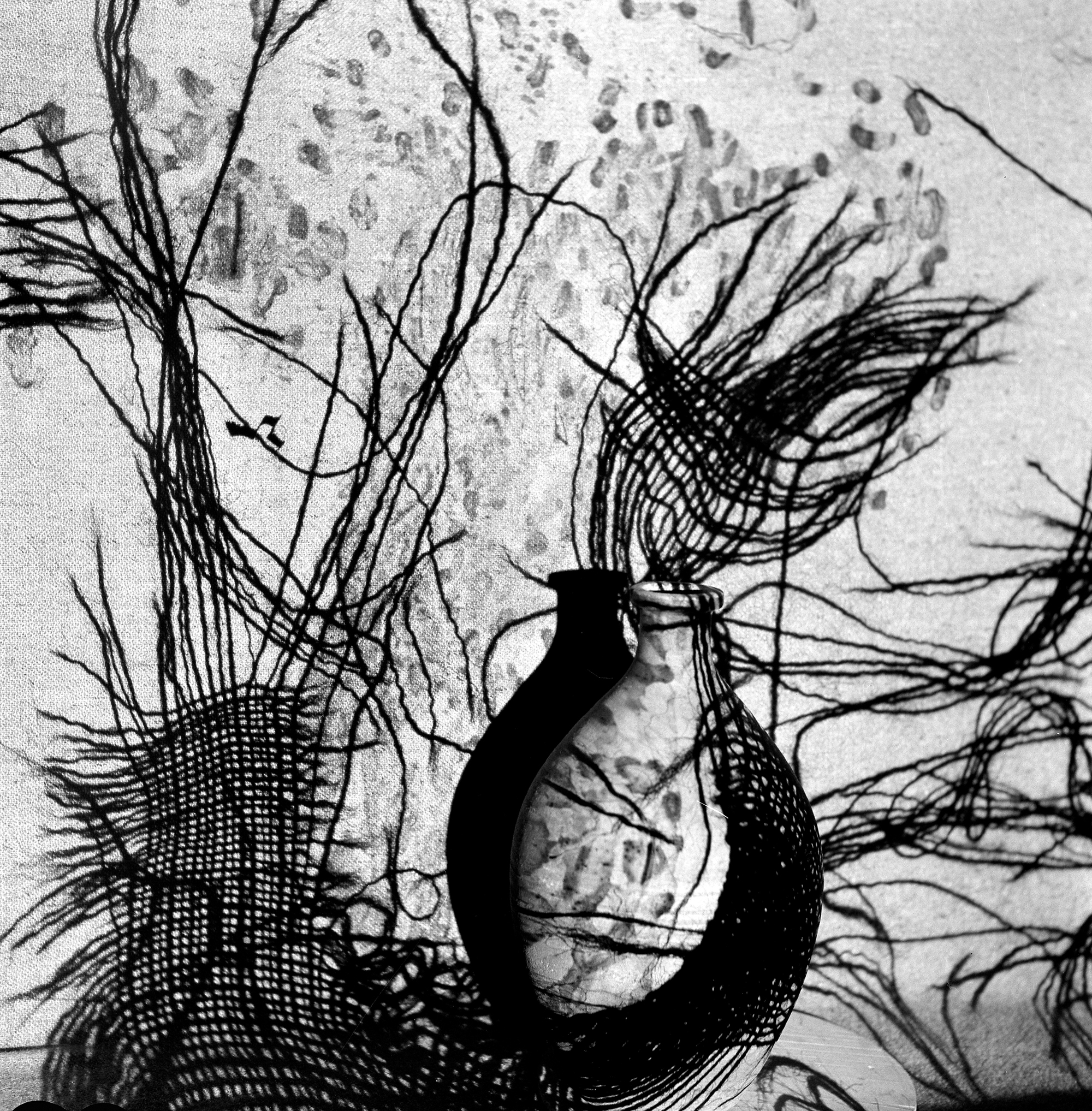

Imai’s life and work embodied a kind of imaginative ambiguity. Her story reveals the most intimate seams between artifice and longing, ecstasy and tragedy. Throughout the late 1950s and the 1960s, she produced a staggering array of experimental imagery, for both personal projects and fashion commissions, establishing herself as the young darling of Japan’s avant-garde photography scene. Born in 1931, in Tokyo, she studied painting at Bunka Gakuin College, becoming entranced by Surrealist art during her studies with designer Souri Yanagi and through conversations with the prominent Surrealist Shuzo Takiguchi. Other giants of the movement, including Man Ray and Jean Cocteau, would also influence her. Imai began casually working with photography while still in art school, after being given a Rolleiflex camera by her father, who ran a photography studio. By her mid-twenties, she was his apprentice and had converted her small room into her personal studio. In 1956, she opened Daydreams, a solo exhibition at Matsushima Gallery, located in Tokyo’s Ginza area, where she presented evocative images of vases, photographed through burlap and buffeted by wind, edges fraying, suggesting otherworldly forms. The show drew the acclaim and interest of prominent critics and artists who had also shown there, including the photographer Eikoh Hosoe, then a pivotal figure. (Hosoe would marry Imai’s sister.)

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

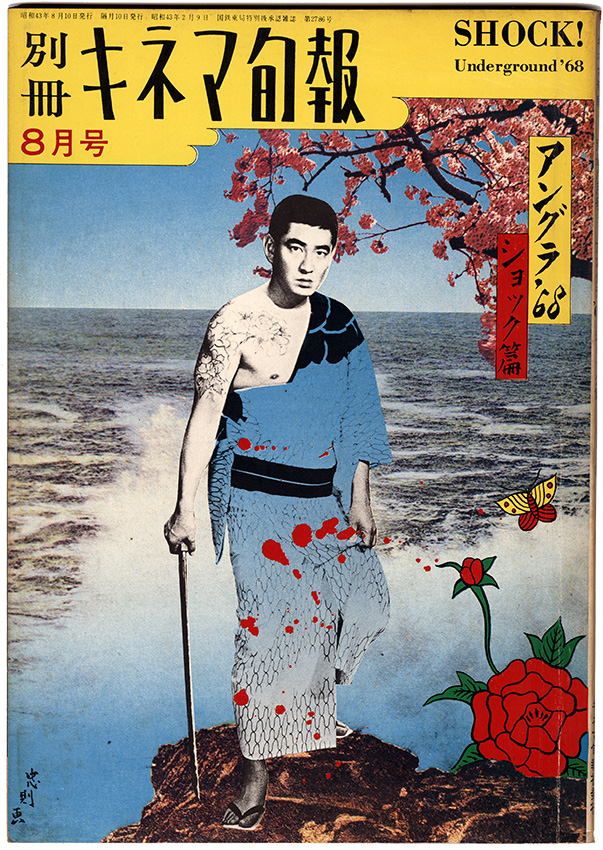

Imai surrounded herself with young, cutting-edge artists. She developed a friendship with Shuji Terayama, the famous theater and film director known for leading the angura (underground) movement, and she was in close proximity to the short-lived but groundbreaking VIVO cooperative, which included Hosoe, Ikko Narahara, and Shomei Tomatsu, among others. The group emphasized the role of subjectivity over the medium’s ability to objectively portray reality. Imai would also take part in a 1962 group exhibition organized by the art critic Tatsuo Fukushima called NON, which stood for “non-tradition, non-section,” at the Matsuya Ginza department store, featuring VIVO members and highlighting new approaches to photographic expression.

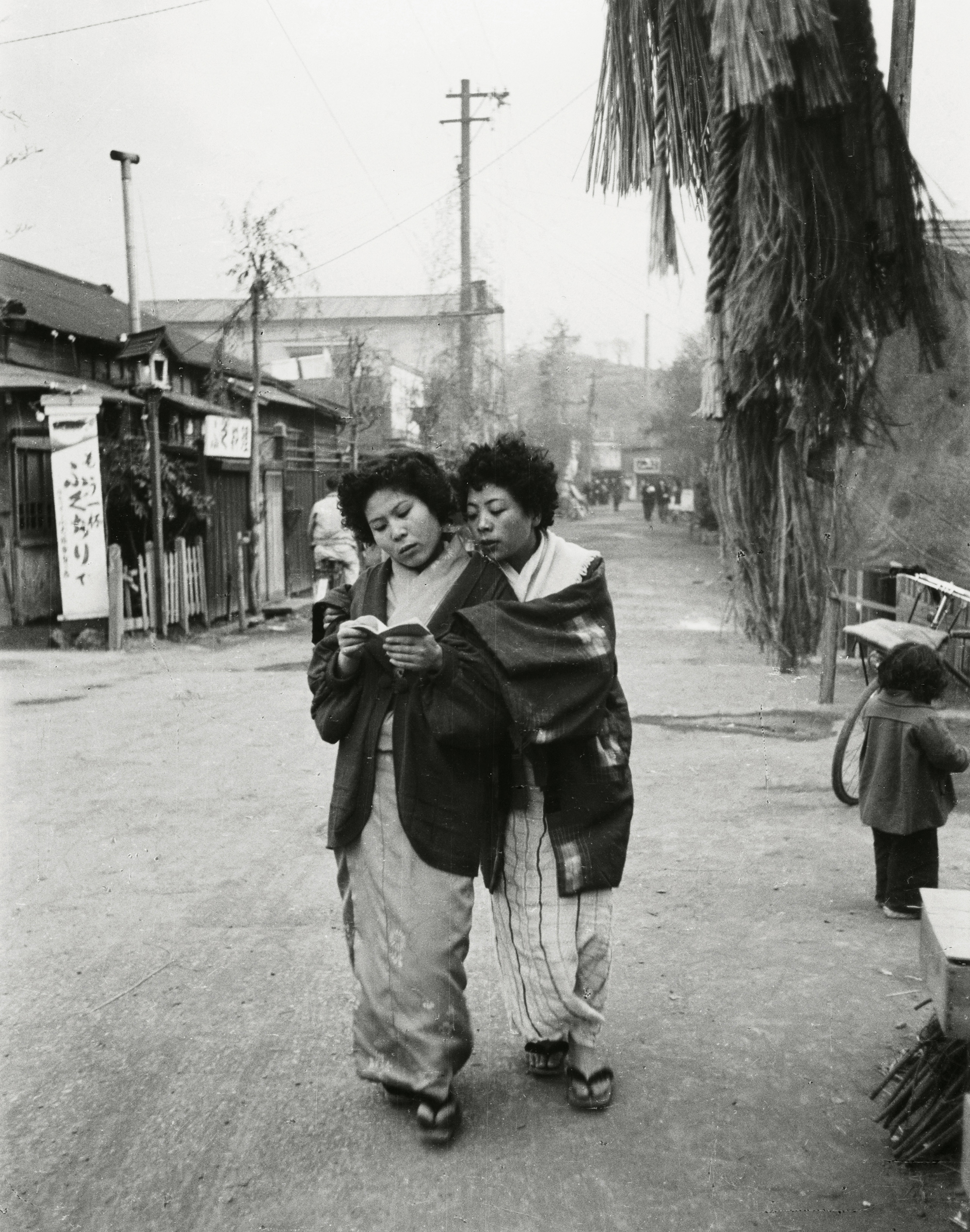

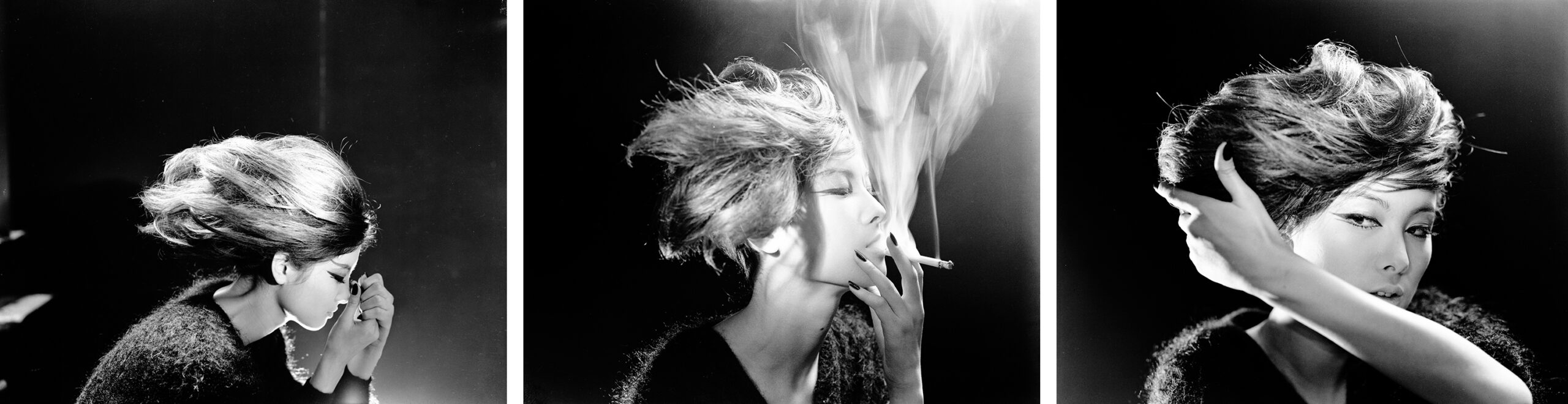

We can feel the sensibility of her peers, and the bold, experimental ethos of the era, in Imai’s use of double exposure, mirrored bodies, and collage. But her photographs stand out for their unique approach to the depiction of the female body, often fragmenting and abstracting form. Her series Memories of Summer (1958) includes a torso with ample breasts. In one photograph, the figure is made out of thin bark, curling and peeling; in another, it is carved out of wooden blocks; in yet another, it is formed from tendrils of hair. The figures resemble a mannequin, doll, or robot in the process of being dismantled or slowly torn apart. Three years later, she would return to this idea, the split female body—but one that is no longer headless—in a solo exhibition at Gekko Gallery in 1961, titled Model and North Wind. The series appears to shift from considering what the models are—taking apart the women and seeing what they are made of—to considering where they exist, which is somewhere pitch-black. These figures float in fields of darkness, immaculately made-up in thick-winged eyeliner, split from context or even clothing.

At this time, Imai was building a successful career in fashion and her photographs were regularly published in magazines. The “fashion,” however, in many of these images seems to be the models’ hair, styled to dramatically undulate, reflect, and absorb light. Hair appears as both a living organism and a person’s dead, ornamental boundary. “Always her hair grows thick, like an unknown plant,” the poet Shuntaro Tanikawa noted, writing about Imai in the June 1961 issue of Camera Mainichi. “Today, as ever, the wind wafts in spores of dreams.”

Hisae Imai, Model and North Wind, 1961

The strong desire to present women in vivid, almost unearthly ways is also visible in Imai’s 1962 photographs of the lingerie designer Yoko Kamoi, who was pictured as a sorceress in a solo exhibition called Sea-born Fantasy. Kamoi had revolutionized women’s lingerie in the 1950s, encouraging Japanese women to wear color instead of white, to be bold, to flaunt themselves. She championed the idea of transforming underclothes from simply practical things—to support, to shape, to cover the body—into garments of feminine pleasure. Kamoi was interested in not simply showcasing the female form but considering the gendered assumptions behind notions of use and uselessness, frivolity and practicality. Imai shared the same spirit. In the stills from the film component of Sea-born Fantasy, Kamoi is surrounded by discarded wigs and beheaded pink doll heads; in another, she compares her height, perched on her tippy-toes, to that of a blond mannequin.

Imai’s photographs stand out for their unique approach to the depiction of the female body, often fragmenting and abstracting form.

By the early 1960s, Imai was ascendant. A profile in the fashion magazine Soen crowned her “No 1. of female photographers.” The article offers every telltale touch of potential for this rising prodigy. Then, one day in the late spring of 1962, all of that changed in an instant when a taxi Imai was in crashed headlong into traffic. For nearly a year, she was blind. Her life entered a tunnel, and the world of artistic ambition fell temporarily dark. The details of this year are scant, but she would eventually recover her sight—and the traumatic accident would significantly alter her life and career trajectory.

In a photograph from the series Fantasy: Eyes and Teeth (1963), made during her recovery, we see, through the shadow of an outstretched hand, what looks like an X-ray, or a plaster cast, of a clenched jaw with a string of beads held between its teeth. The scholar Masako Toda, who has researched and written extensively on Imai, asks us to pay particular attention to the physicality of these photographs, which deliver a visceral charge. “There is probably a close relationship between her experience of almost losing her sight due to the accident and these painful-looking works of eyes and teeth,” Toda writes. “This series of photos is very physical, and possesses an intimate feel.” What is most affecting is not just the clenched jaw, or the forensic feeling, but the addition of the beads—the decorative ornament added, or grasped for, right when the X-ray turns a person into an image of yet another body to be operated on.

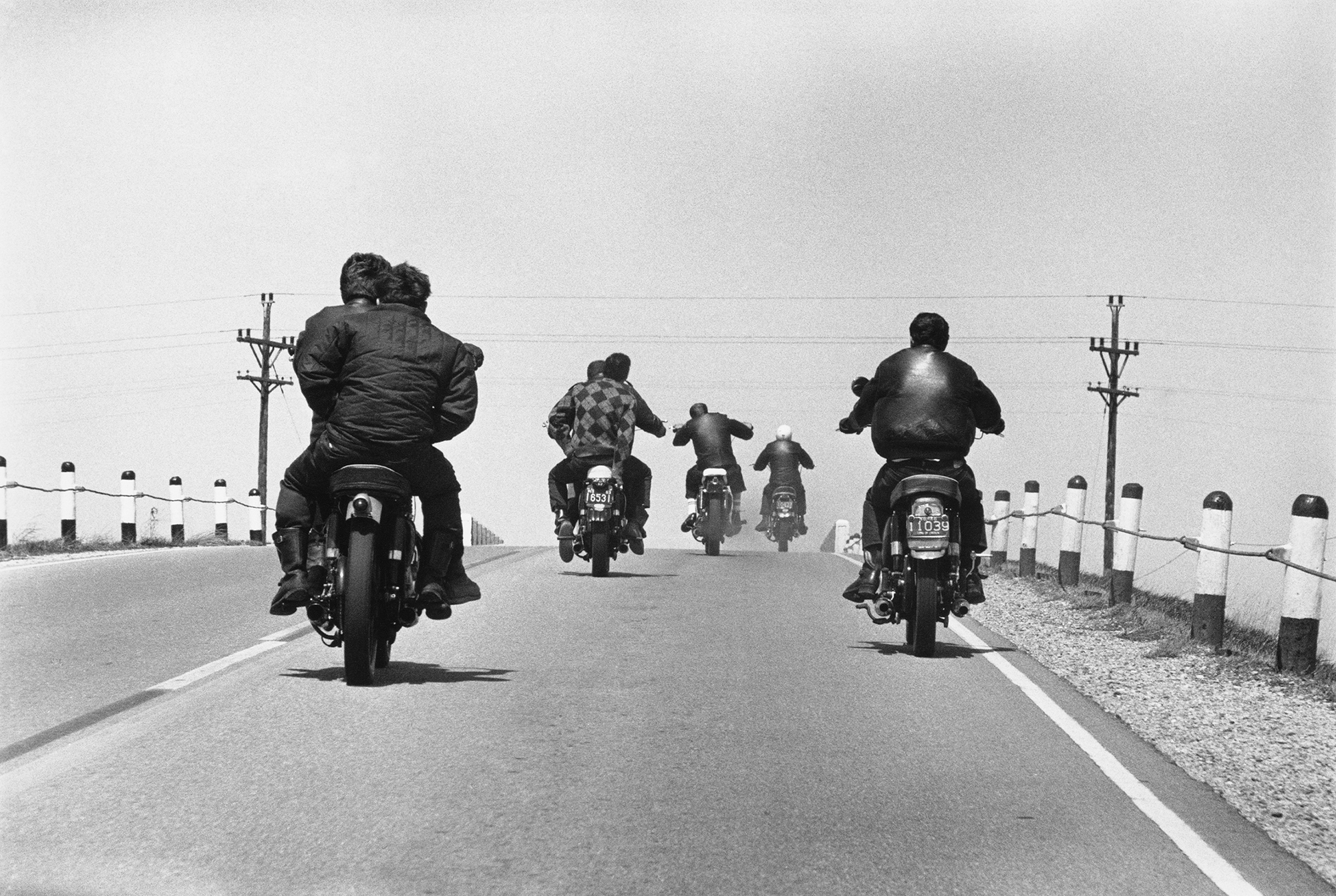

After her accident, the human body would concern Imai less and less, replaced by a newfound interest in the natural world, horses in particular. The story goes that on a bright day in 1963, her vision finally restored, Imai walked into a movie theater and watched David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, the three-and-a-half-hour epic in which the most prominent four-legged animal is a camel, not a horse. But there was something about the horses featured in the film that stirred her; she left her photography studio behind to work in stables and open fields.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy the Third Gallery Aya, Osaka

“Do I go out to see horses because it hurts to wander around, so aimless?” Imai asked in her 1977 photobook Hippolatry: Enchanted by Horses. For the last forty years of her career, trekking from Hokkaido to the Isle of Man, Imai would relentlessly, and beautifully, photograph racehorses. She became a visual poet of jockeys emerging from a haze, of the starched rituals and clamor of a race track, of the curve of a foal’s neck. She immersed herself in the rush and quiet of a life lived among horses. For her, the animals represented not the primal overcoming of a frontier, like they do

in a Western, nor the pedigreed lure of cultural capital, as they do in Ralph Lauren advertisements, but the evocation of a threshold, the feeling that they can bring us over to another world. In one photograph, a white horse angles out of pitch darkness—in another, horses are brown dots racing against a sky of yellow grain. To these images, she added odd textures and color—not glitter or shine or rose petals, as she did to her female figures. Here clouds are streaked, variegated into pinks and blues. Manes are tinted with color and mists evoke an otherworldliness that Imai must have felt they contained.

Her photographs, through all their range and experimentation, dare viewers to consider what it means to have a second life, and to consider the selves that can be discovered in dreams, summoned in solitude, or encountered outside in the world. The gallerist Aya, of the Third Gallery Aya, who recently exhibited Imai’s work, emphasized in a conversation with me the importance of the “after,” such as in After Ophelia. In a 1962 essay she wrote about her collaborations with Imai, Kamoi asked: “Was her work a longing for a glimpse of the afterworld, or was it a challenge or protest against this world, the world of the living?” The women and horses of Imai’s photographs hover at this threshold and, in their lush metamorphoses, ask how we might disentangle longing from flight, the living from those who come after.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire.”