Essays

The Possibility of Home

Asian American photographers have always found inventive ways to engage with interior spaces, often against the demands of public visibility.

Courtesy the artist

A panel of solid black is interrupted by fragments of human form: an elderly woman stepping halfway into the frame, her expression animated by something in the dark. Down by her side, a sliver of a child’s face peeks out with one curious eye. In front of them, a floral-patterned bandana levitates in midair, as though to suggest the presence of some phantom we can’t see. In Passing, taken in 1969 in San Francisco’s Chinatown, reflects the intuitive gaze of a longtime local. It is a mode of looking that is at once attuned to the intricate sociality of one’s own community and unconcerned with accommodating the needs of an outside viewer, registering instead rich stretches of ordinary life as darkness.

The artist, Irene Poon, spent many years photographing the neighborhood of her youth, weaving dreamy images out of the fleeting faces and encounters of everyday life. As her contemporaries Charles Wong and Benjamen Chinn had begun to do a decade earlier, and previous generations of Chinatown photographers, such as Mary Tape, had done as early as the nineteenth century, Poon used her camera to replace the distant, exoticizing gaze of the tourist with that of an intimate insider caught up in the same quotidian rhythms as her subjects. But her work also goes further: Poon’s most striking compositions feature dense black areas that shroud and fragment her subjects, like blind spots made visible.

© the artist and courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

In Memories of the Universal Café (1965), a forearm hovers, disembodied, over a table of food. In Fire Crackers Await (1969), a woman in apron and slippers floats in negative space at the bottom of a staircase. Often, the enveloping blackness shows up as background while figures linger at thresholds—doorways, balconies, windows—a recurring motif, marking the unseen interiors from which they emerge and into which they can retreat. Poon usually lets in just enough details to suggest that the negative spaces aren’t empty but rather full of presences we can’t see. Curiously, Poon honed this aesthetic of visible invisibility just as the political awakening of the Asian American movement swept through the campuses of the Bay Area and beyond, including Poon’s own alma mater of San Francisco State College.

What does it mean at this historic moment to turn one’s camera toward the banal details of ordinary life, to center the familial figures of children and grandparents, and, what’s more, to cast them on the edge of spatial indeterminacy, to allow them to go dark? If the Asian American movement sought to forge a clear political identity for Asians in the United States—as multiethnic, oppositional, anti-assimilative—then Poon’s work opens onto the obverse: the messy, exploratory, unfinished private spaces and relations that sustain such acts of public self-definition. If Asian America is built on generations of activism, Poon’s shrouded compositions remind us that it is also built on generations of what the performance scholar Summer Kim Lee calls “staying in.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Staying in, writes Lee, “critiques the compulsory sociability and relatability demanded of minoritarian subjects to go out, come out, and be out.” To stay in isn’t to cut off relations with others but only to refuse to be relatable—that is, to act in ways that conform to the standards and values of an outside public. For Asian Americans, to stay in means to slip out of our assigned roles within a visibility predicated on binaries of injury and protest, trauma and resilience—as entrenched as ever in our era of anti-Asian hate. Staying in opens up other registers of sociality: of rest, pleasure, play. It encapsulates the banal, domestic, familial spaces and relations that make up the substance of our lives but leave little trace in history.

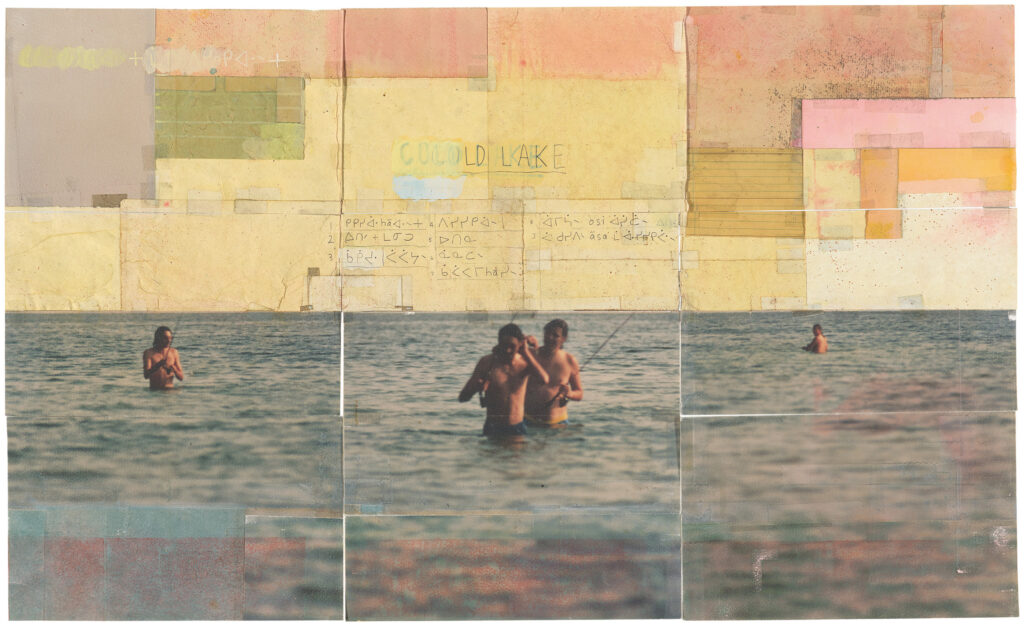

As one of the few places to register this history of “staying in,” Asian American photography before and since Poon has found inventive ways to engage with such interior spaces and relations, often against the demands of public visibility, sociability, even legality. Take, for example, the phenomenon of the composite family portrait, which emerged in the early twentieth century to create what the art historian Thy Phu calls a “counterarchive” of familial intimacy in the era of Chinese exclusion. In the 1920s and ’30s, a time when Asians were effectively banned from entering the United States, Chinese American photography studios used collage techniques to piece together portraits taken thousands of miles apart, visually reuniting family members separated, sometimes for a lifetime, by racist immigration policies.

© and courtesy Wylie Wong Collection of May’s Studio Photographs and Special Collections, Stanford University

© and courtesy Janet M. Alvarado, San Francisco

May’s Photo Studio, which was opened in 1923 in San Francisco’s Chinatown by the husband and wife Leo Chan Lee and Isabelle May Lee, made such portraits for those in their community. One example shows a family of six posing against the backdrop of an ornate interior. The wife and husband sit at the center, on either side of a table, a set of teacups between them, as though they will momentarily turn toward each other to take a sip. But the illusion of togetherness is broken by the flatness and unnatural glow of the husband, the only one in Western attire. A closer examination reveals the rough outline that snakes along his head and shoulders like stitches, a sign that he has been cropped from another photo, a place an ocean away. At a moment when studio portraiture had become a government tool to track Asian bodies via the introduction of photograph identification documents, Chinese American studios found a different use for photography: to weave together dream interiors of familial wholeness and imagine a utopian space without borders.

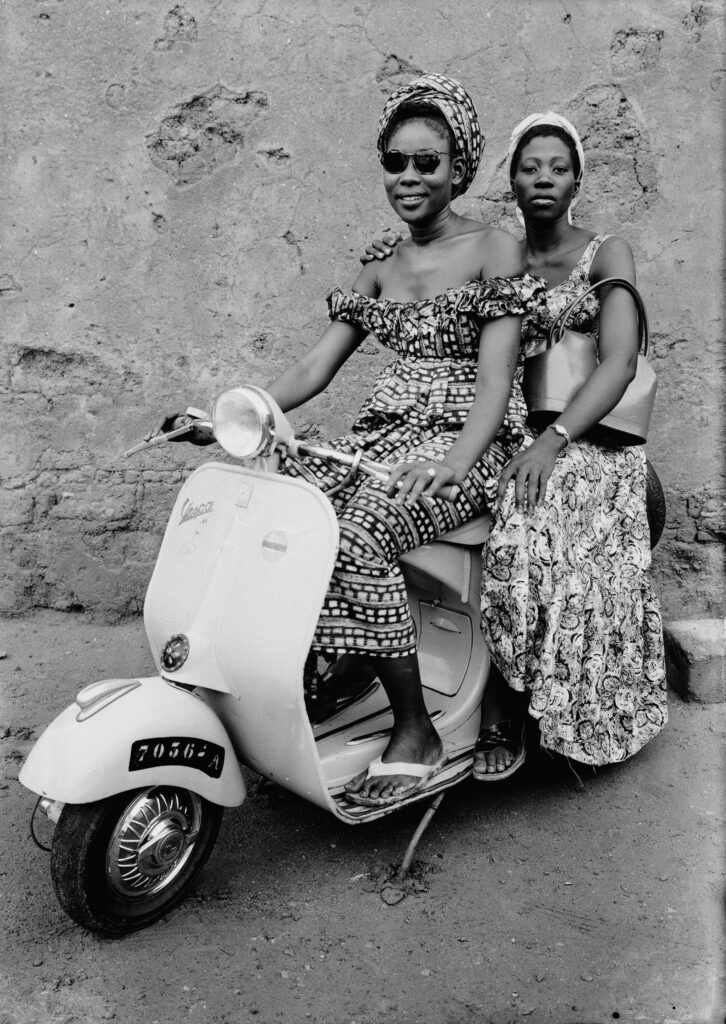

Ricardo Ocreto Alvarado provides another vision of “staying in” through his photographs of house parties in the 1940s and ’50s. Alvarado, who had no formal photography training and worked as an army hospital cook by day, brought his Speed Graphic camera to countless gatherings of friends, family, and relatives within San Francisco’s growing Filipino American community. Taken in an era when segregation kept people of color out of many restaurants, clubs, and other mainstream social settings, Alvarado’s photographs center the private home as a precious site for nourishing an otherwise impossible social world.

What does Asian America look like from the inside? What does it mean to live in the blind spots of American history?

In one photograph, a sparsely furnished room is offset by its buoyant inhabitants spilling out from the top of the frame. Handsomely dressed parents, children, and relatives gather in loose rows as though for a group shot, but only half look at the camera; the others are engrossed in their own micro-dramas—eating, crying, daydreaming—creating a rich tapestry of crisscrossed gazes. Near the center of the group, the beaming host turns away from the camera to offer up a heaping plate of lechón (roast pig) to her guests, further derailing any attempt at a standard pose.

Alvarado’s interior scenes often include other minority friends and coworkers, from the same area in San Francisco, whose communities overlapped and merged with Alvarado’s own. A live band of Filipino, Black, and Latino musicians play at a house party; interracial couples dance, hands loosely interlaced, in a living room draped with streamers. These figures, open and carefree before the camera, owe their casual radiance perhaps to a sense of safety in the presence of the photographer. Like Poon, Alvarado inhabited the spaces he photographed, resulting in images that tend not toward public display but shared interiority, the pleasure of enclosure, the relief of “staying in.”

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Like their fleeting subjects, photographs of Asian American interior life—real and imagined—occupy a tenuous place in American art history. Both the work of Alvarado and May’s Photo Studio were buried away for decades and rediscovered only by chance. Alvarado’s daughter stumbled upon some three thousand negatives in the basement of their home after her father’s death in 1976. A young art student on a walk encountered and rescued from a Chinatown dumpster the archive of May’s Photo Studio in 1978, after its owners had passed away. Still, home spaces, familial relations, the vast terrains of quotidian time: these remain abiding interests in Asian American photography. In recent years, a younger generation of artists has waded into the interior world of “staying in,” finding new strategies to contemplate the secret histories it enfolds, the legibility it withholds.

Often, these photographers begin with the site of their own home, using the camera to perform an excavation of the everyday, to see anew the banal details that usually fade into the background. In the series Of Light, Dust and Passing (2011), Julie Quon photographs her family home in New York’s Chinatown, where her parents have lived since 1980. Still living with them at the time, Quon lingered over ordinary objects bathed in early morning light, seeking out the incidental traces that index her parents’ particular presence, without needing to show their faces: her mother’s slippers under the chair, her father’s cigarettes hidden behind the radio, the makeshift dust covering over the washing machine. These still lifes reflect Quon’s architecture training with their clean lines and geometric compositions, but they are also portraits, years in the making, that patiently tease out the inner lives of their elusive subjects through a visual vernacular of the quotidian.

Courtesy the artist

© and courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures Generation, New York

Miraj Patel takes the portrayal of the family home in a different direction, using elements of performance and self-portraiture to create playful, moody meditations on immigrant life in American suburbia. He began the series Do you see what I see, when I look at me? (2020–present) while cloistered at home with his parents during the first year of the pandemic. In one image, Sunday Morning (2020), Patel snuggles in bed with his parents and dog, reenacting a childhood ritual; this unusual arrangement of bodies contrasts humorously with the generic, symmetrical furnishings of the room. Other photographs show Patel creatively misusing various corners of their home. These performative interventions heighten a sense of incongruity between the Southern California house, a symbol of assimilation and upward mobility, and its Indian American inhabitants. “In trying to fit into the cookie-cutter formula,” Patel pondered, “what is this third thing we exist as?”

Likewise, Tommy Kha, whose family was part of the Chinese diaspora in Vietnam before immigrating to the United States, recalled noticing as a child that his house was “set up differently” from those of his friends: “every room had different walls and textures.” In his series Shrines (2013–ongoing), Kha explores this distinctive heterogeneity by tracing the presence and placement of religious and ancestral shrines, first in his own home, then in the homes and businesses of others across Memphis and New York. Kha calls the mismatched assemblage of incense holder and offerings in Stations (Kitchen God) (2015) “my mom’s curation”; set amidst other details bearing her touch over the years—a large burn mark on the counter, aluminum foil lining the stove tops and range hood—it forms a palimpsest of immigrant life. “It was a part of my childhood,” Kha said of the shrine, “but no one ever explained the ritual to me.” The project thus began with a reconfiguration of Kha’s own vision, a shuffling of the background into the foreground. For the past seven years, Kha has photographed more shrines—in restaurants, stores, and multigenerational homes—in an effort to locate and survey a shared, everyday Asian American iconography.

Jarod Lew, Please Take Off Your Shoes, 2021

Courtesy the artist

Jarod Lew similarly tries to find a shared language of the home in his series Please Take Off Your Shoes (2016–ongoing), which took him to the houses of relatives, friends, and strangers around Michigan and San Francisco. Lew, whose work is featured in a portfolio in this issue, began the series as much to seek community as to make pictures, an interest reflected in the deeply collaborative nature of his process. “A lot of these photographs stem from conversations I have with the person I’m photographing, building trust, coming up with ideas of portraying them in a way they’re comfortable with,” Lew told me. Like Quon, Lew looks to still life as the key to portraiture. In his unwavering attention to some of the most mundane sights of domestic life—furniture covered with sheets, a plate of cut fruit, shoes by the entrance—there is an argument about the home itself as performative, a rich sensory world that wordlessly conveys entire histories of intimacy, relation, and feeling.

What does Asian America look like from the inside? What does it mean to live in the blind spots of American history? For over a century, Asian American photographers have explored these questions by crafting ways of seeing that paradoxically protect from the trap of visibility, the trap of being defined by external policies and historical flashpoints. By treasuring the least remarkable recesses of everyday life, these photographs enact radical shifts in vision. To see ourselves in the shared spaces of staying in, unburdened by legibility or relatability—this, they suggest, is the only kind of seeing that will free us.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.” Xueli Wang’s research was supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.