Essays

The Woman Who Immortalized the Bauhaus

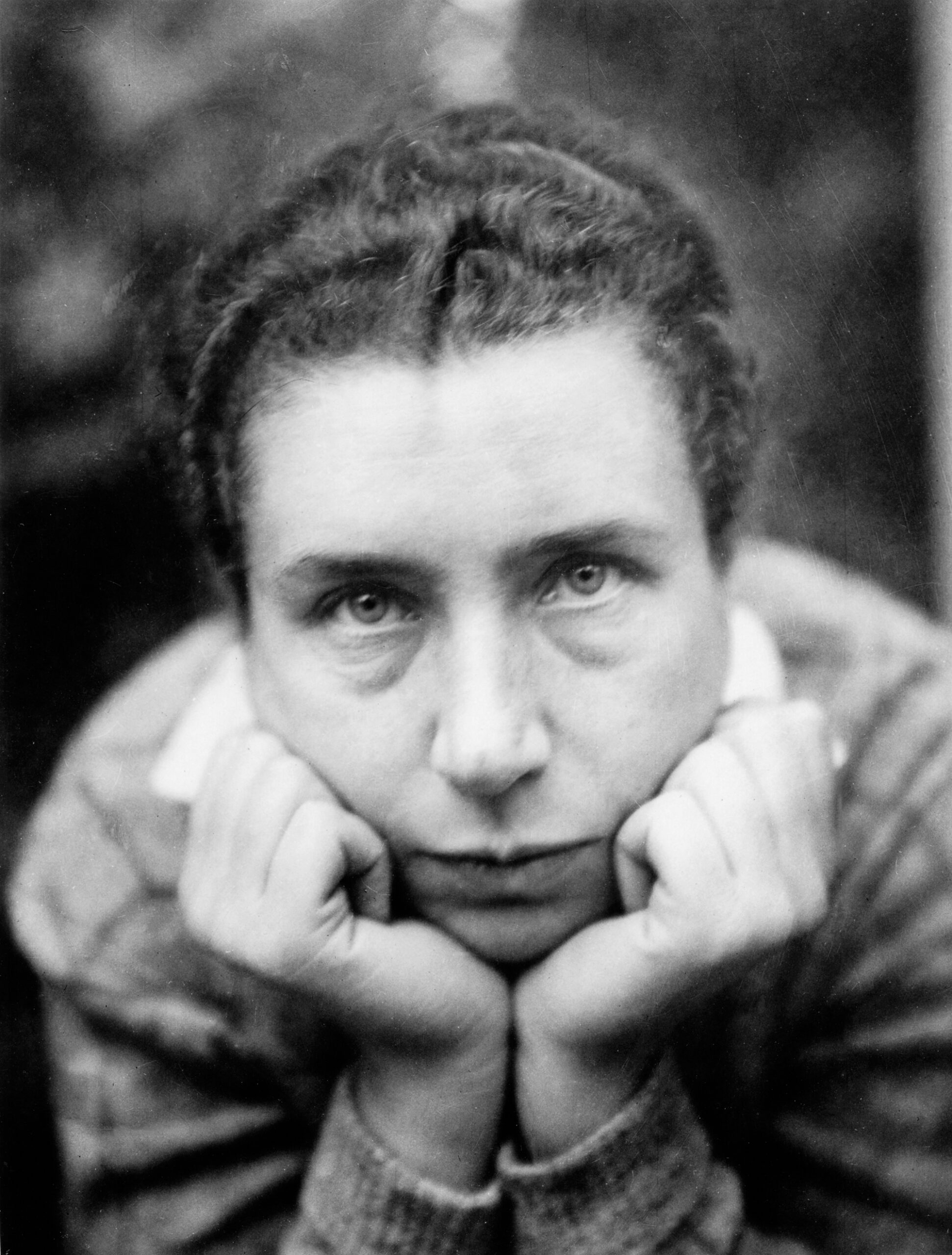

Lucia Moholy’s photographs helped define the visual identity of the Bauhaus. Why was she left out of its history?

Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

“I want to tell you that we are on unfriendly terms with her lately and that she has even brought or intends to bring a suit against Walter for having kept her Bauhaus photographs to himself. There are hard feelings on both sides,” wrote Ise Gropius, wife of Walter Gropius, the German architect and founder of the Bauhaus art and design school, in a 1956 letter to a friend who was hosting a dinner in his honor in London. Ise Gropius was eager to ensure that “she” would not be invited.

“She” was Lucia Moholy, the Czech-born photographer whose mid-1920s images of the Bauhaus campus designed by Gropius in the German city of Dessau have long been regarded as archetypal depictions of the modernist aesthetic. Her precise, beautifully composed photographs of the school’s architecture, students, teachers, and their work still define our perceptions of the Bauhaus as a progressive, empowering bastion of cultural and social idealism. They swiftly became more famous than the woman who made them.

Courtesy Galerie Derda, Berlin

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Lucia Moholy: Exposures, an exhibition presented in 2024 at Kunsthalle Prague, in the Czech Republic, and at Fotostiftung Schweiz, in Winterthur, Switzerland, this past spring, sought to change that by exploring the full scope of Moholy’s work in writing, editing, and documentary filmmaking as well as photography. But why was such a gifted and charismatic woman overlooked for so long? And why, for much of that time, was she not credited for her most important body of work? The answers lie in the misogyny and geopolitical turmoil of mid-twentieth-century Europe.

Born Lucie (she later changed her name to Lucia) Schulz to nonpracticing Jewish parents in Prague in 1894, she had a comfortable childhood thanks to her father’s successful law practice. As part of the first generation of European women (albeit only wealthy ones) to be encouraged to attend university, she qualified as a German and English teacher in 1912, then studied philosophy and art history at the University of Prague. After spending much of World War I in Germany, first in Wiesbaden, then Leipzig, she settled in Berlin and worked in book publishing while writing experimental literature under the male pseudonym Ulrich Steffen. By then, she was part of an avant-garde group of intellectuals, artists, and activists who were devotees of a Mazdaznan sect, which advocated meditation, strict vegetarian diets, and a bracing exercise regime of wild swimming and hiking in the countryside.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

In 1920, Schulz fell for a recent arrival to Berlin, a young Hungarian artist and activist named László Moholy-Nagy. A few months later, they married, and she changed her surname by adopting the first part of his, becoming Lucia Moholy. At the time, László was focused on applying his work in painting and collage to securing radical political change. During their country walks, he began experimenting with photography, then widely dismissed as being too sentimental and commercial to have cultural value. Lucia contributed heavily to his program for what he called a “new vision” and swiftly developed photographic concepts and techniques of her own. As well as collaborating with László to create photograms by printing images of objects, or their shadows, on photographic paper, she explored innovative ways of presenting daily life using a camera. They both believed that photography was an exciting means of documenting the speed and urgency of modern life, and its dangers.

Subsisting on her modest wages, they had so little money that they could not afford to heat their apartment in the brutally cold Berlin winter. Their fortunes changed after the success of a 1922 exhibition held at Der Sturm gallery in Berlin, which included László’s “telephone pictures,” made by a sign factory in accordance with instructions he relayed by phone. Among his new admirers was Walter Gropius, who was so impressed by László’s intellectual vigor that he invited him to teach at the Bauhaus, which was then in Weimar.

© ProLitteris, Zurich, and courtesy the collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

© ProLitteris, Zurich, and courtesy the collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

When the couple arrived in 1923, the four-year-old Bauhaus was in chaos. Under attack by conservative local politicians, who derided it as a hotbed of subversion and depravity, it was still scarred by a long-running conflict between Gropius and a charismatic teacher, Johannes Itten, who favored a mystical approach to art and design education. As Itten ran the foundation course, which was compulsory for all incoming students, he exercised considerable influence until Gropius ousted him in 1922.

Gropius hired László to replace Itten, judging correctly that he would have a very different vision for the school. László reinvented the Bauhaus in accordance with Constructivist principles by urging the students to deploy art, design, science, and technology to improve the lives of the masses. He also allowed women to study the same subjects as men, rather than being relegated to supposedly “feminine” courses, principally weaving.

Unlike many “masters’ wives” who were uninvolved with the school, Lucia played an active role at the Bauhaus, notably in her unofficial capacity as resident photographer.

As for Lucia, she began a two-year apprenticeship with the photographer Otto Eckner, who was then responsible for documenting life at the Bauhaus. When the school moved to Dessau in 1925, she enrolled in photography classes in nearby Leipzig, and set up a darkroom where they could continue their experiments in their home, one of the tellingly named “Masters’ Houses” designed for Gropius’s almost all-male teaching staff.

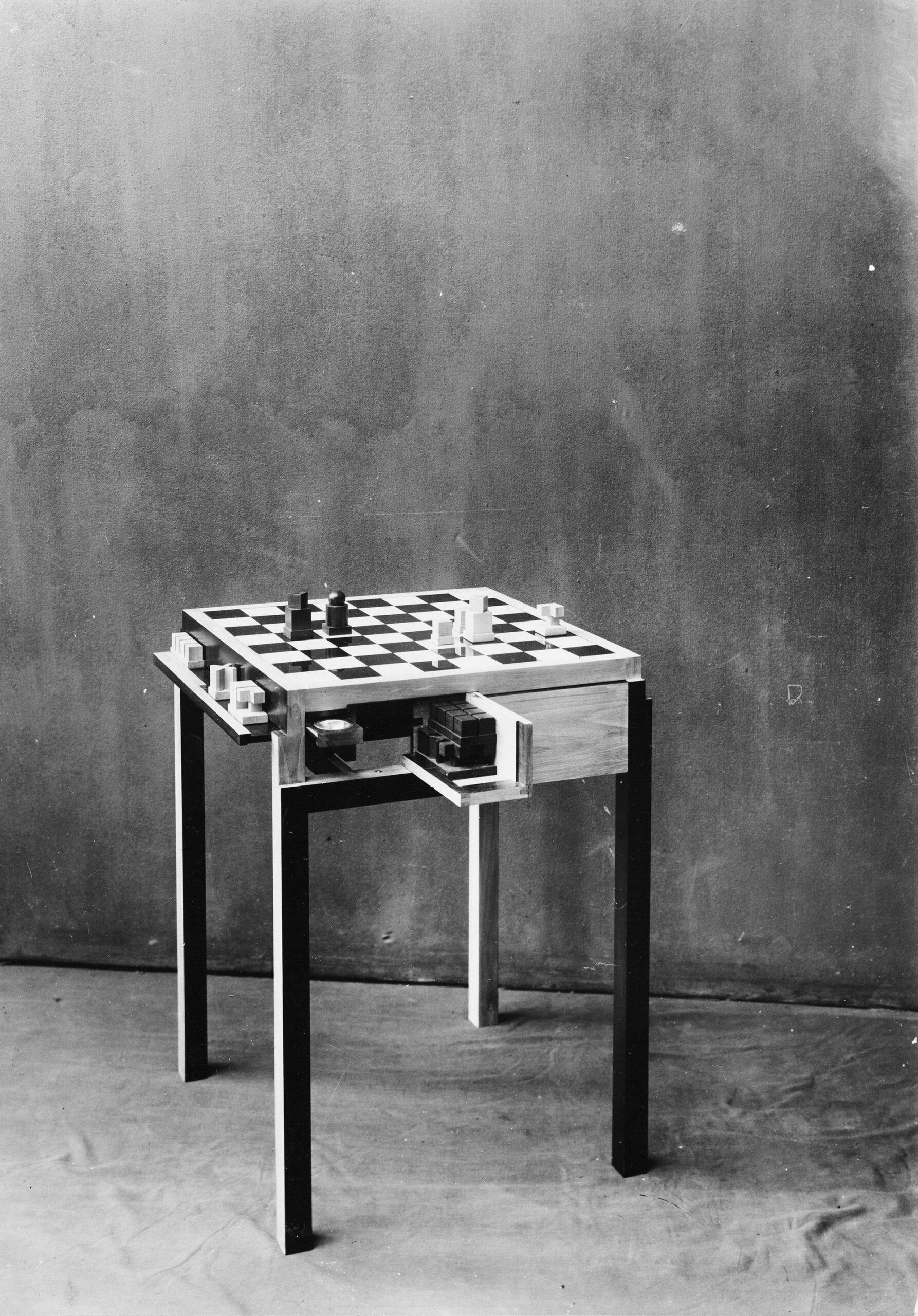

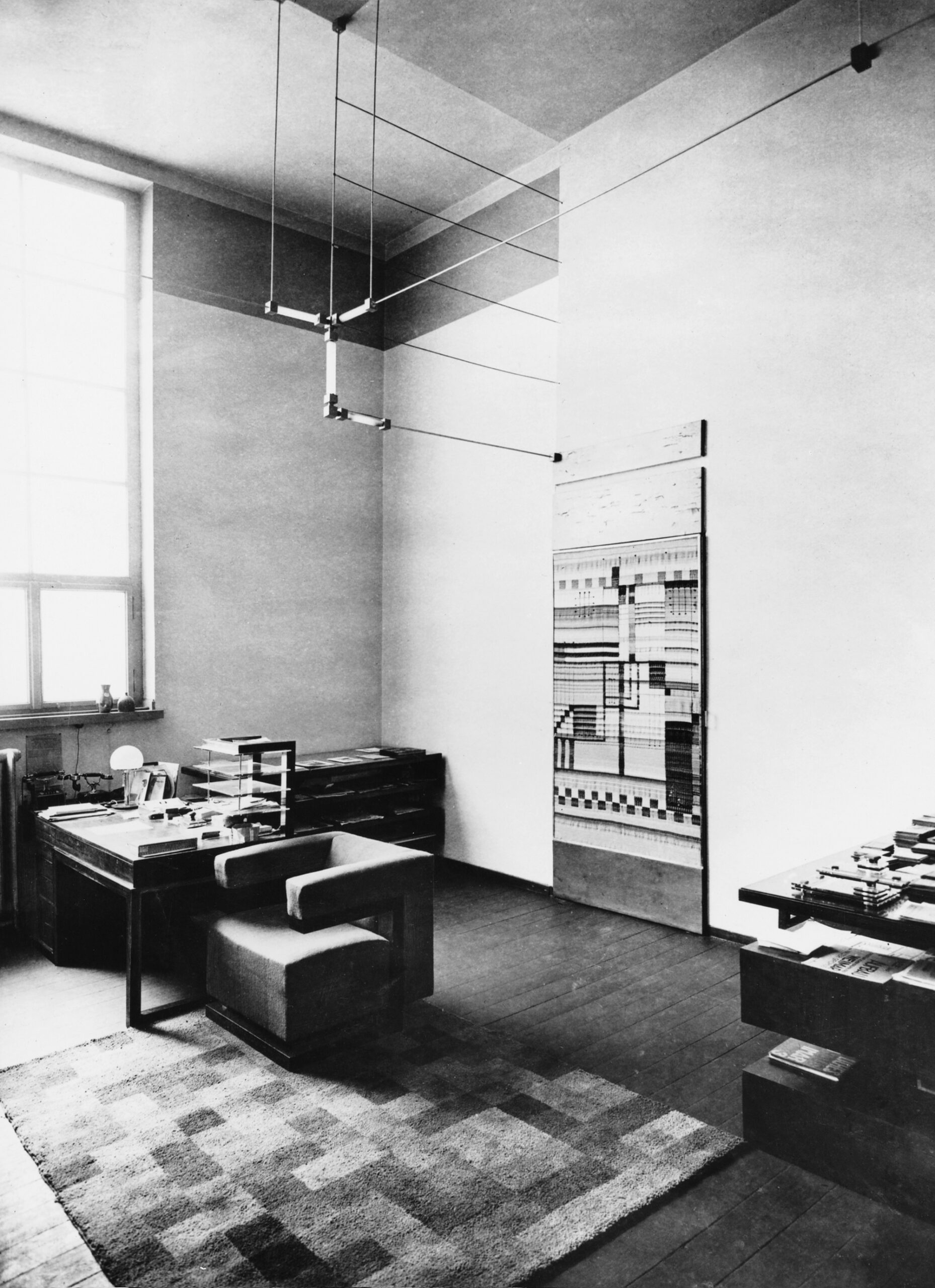

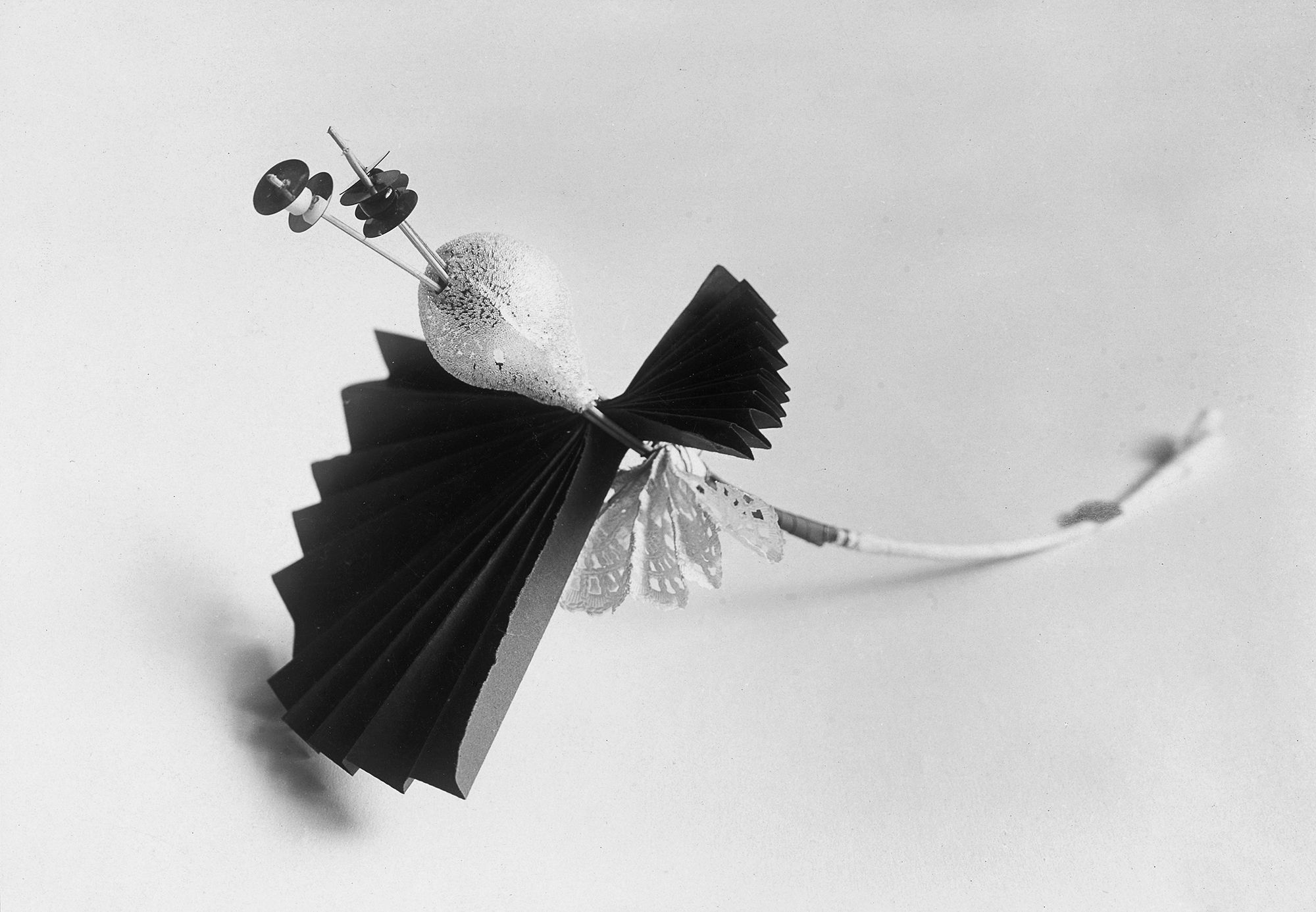

Unlike many “masters’ wives” who were uninvolved with the school, Lucia played an active role at the Bauhaus, notably in her unofficial capacity as resident photographer. Her still lifes of objects designed by the students—including Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel B33 chairs, Marianne Brandt’s silver and ebony teapot, and a corsage made by the Bauhaus weaver Gunta Stölzl—defined a radically new style of industrial photography. Using primarily an old plate camera for 18-by-24-centimeter glass negatives, she made the object the sole focus of the image, always positioning it against a neutral backdrop. As the design historian Robin Schuldenfrei noted in a 2013 essay, “The products’ modernity is underscored in the photographs themselves: in the shiny reflective surfaces, lit so that they gleam but do not over-reflect.”

© ProLitteris, Zurich, and courtesy the collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

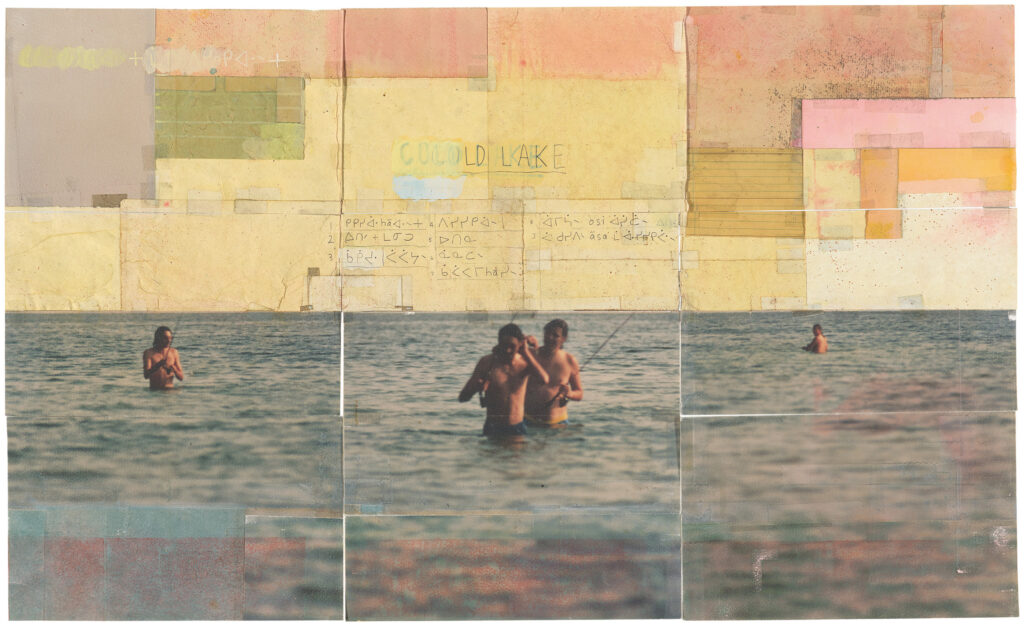

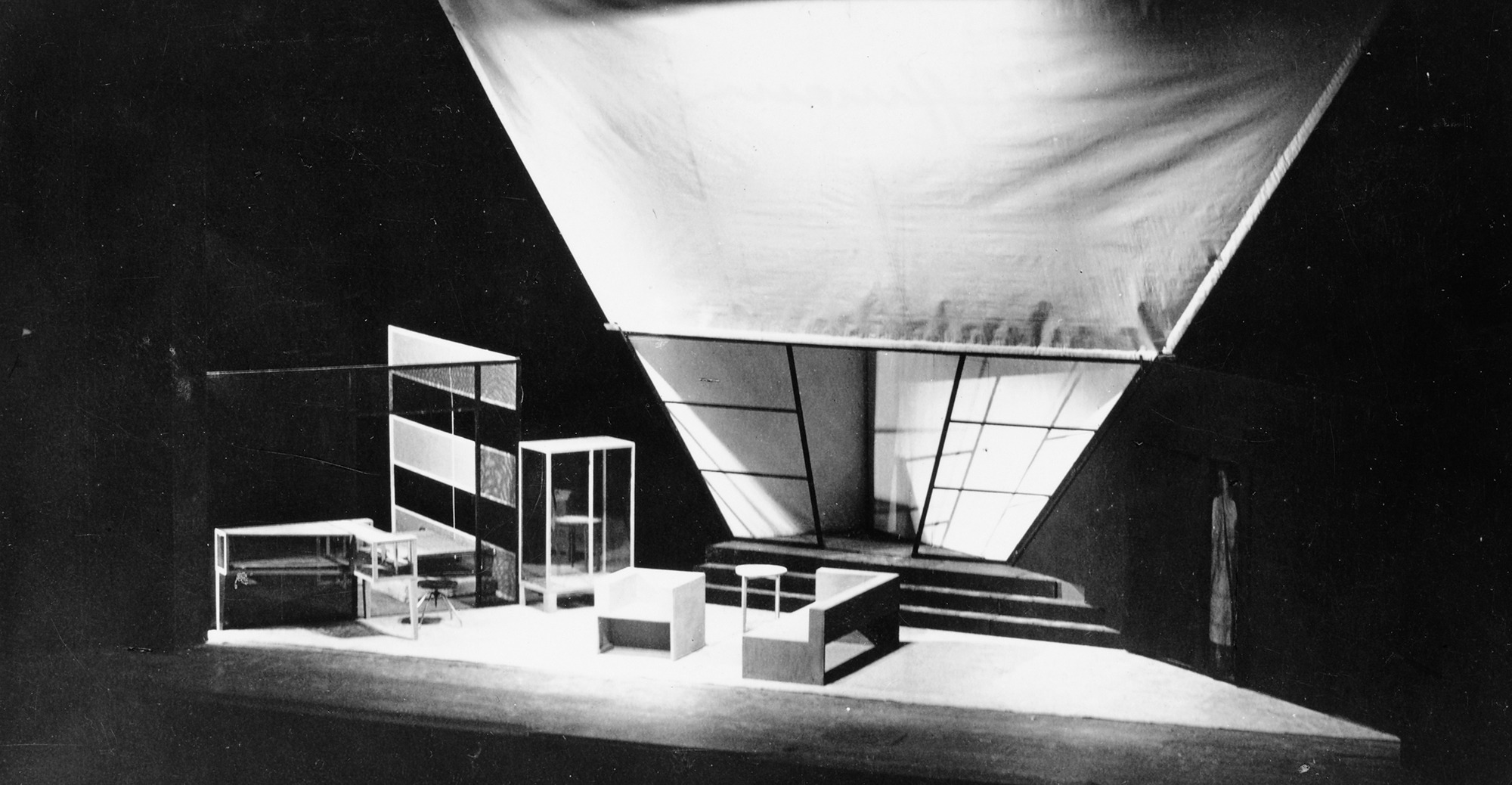

Lucia applied a similar methodology when documenting the evolution of the Bauhaus Dessau, starting with its construction before focusing on each completed element, including the learning spaces, theater, canteen, student apartments, and teachers’ houses. Each of these immaculately composed photographs was taken in a painstakingly planned, seemingly dispassionate style that depicted the school as a series of stage sets, devoid of people. (Lucia also photographed the stage sets designed by László at Berlin’s Kroll Opera House.) They convey a sense of elegance, modernity, and discipline that has defined the Bauhaus, and modern glamour, ever since.

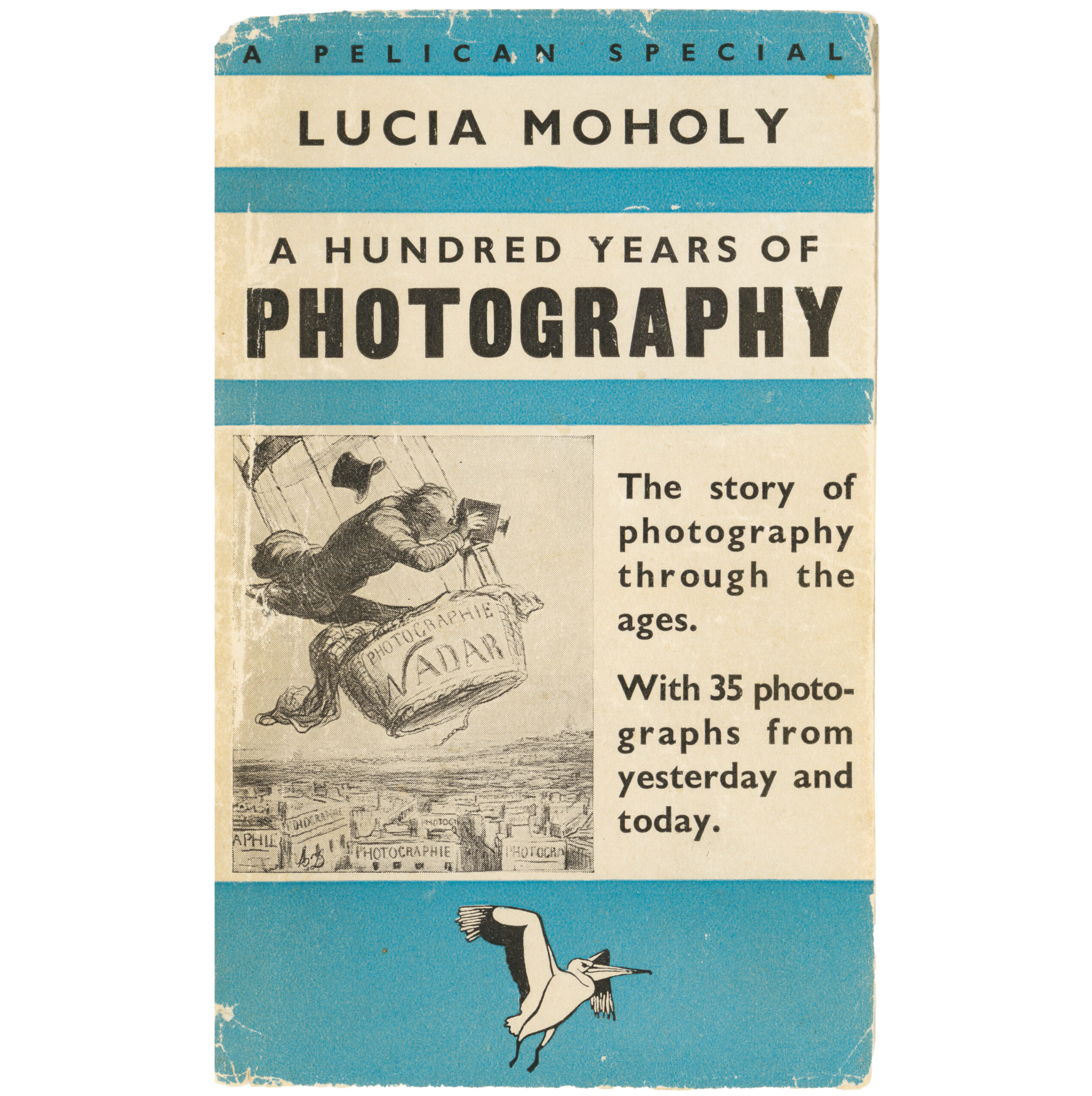

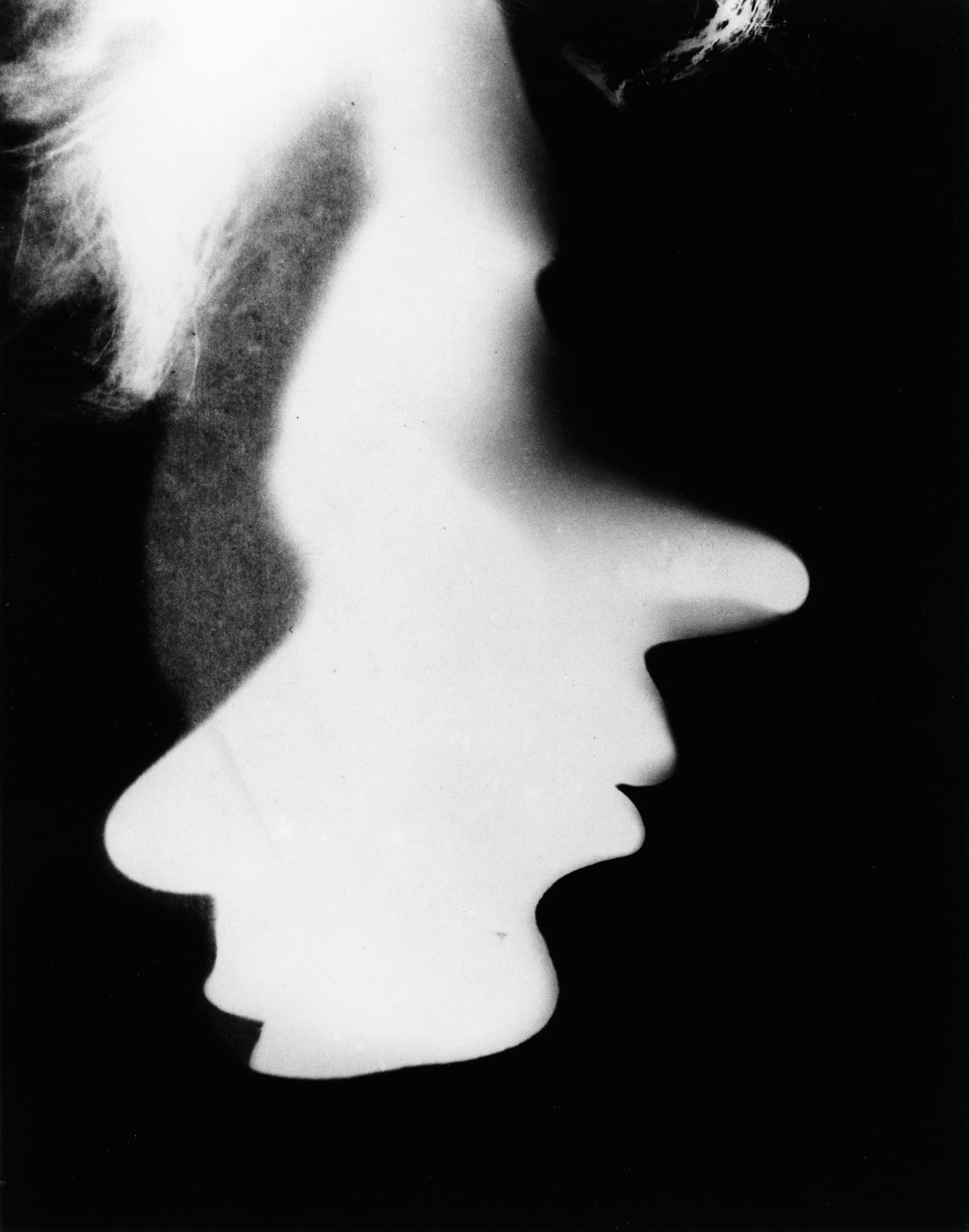

Her portraits from this period share many of those qualities, not least by tightly cropping her subjects’ faces to emphasize nuances of their characters while forging a rapport between them and the viewer. In her 1939 book A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939, Lucia cited the extreme close-ups used by Sergei Eisenstein and other avant-garde Russian filmmakers as an inspiration, despite the misgivings of some of her subjects. “They find it interesting and worth discussing,” she wrote, “but few of them wish to have their portraits taken in the same way.” Tellingly, many of her most cooperative sitters were women, often friends, such as the German photojournalist Edith Tschichold and the New York–born artist Florence Henri, who arrived at the Bauhaus as a painting student, only for László and Lucia to convert her to photography.

Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

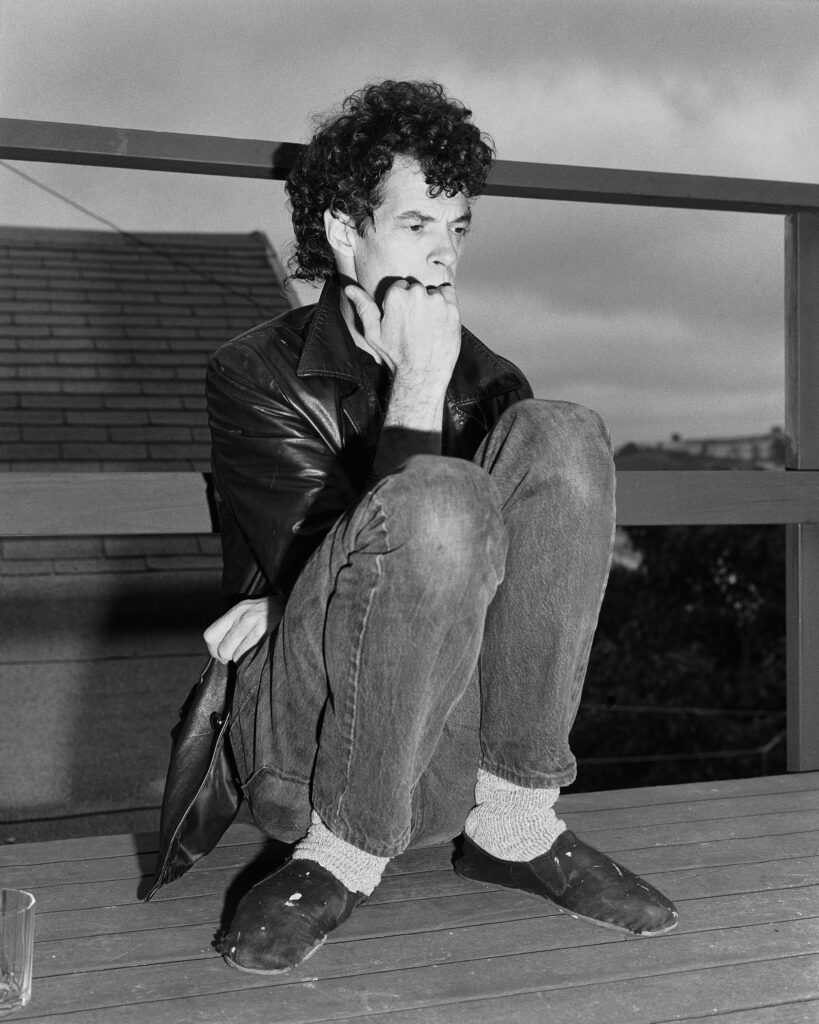

Equally enthusiastic were the occupants of Schwarze Erde, a feminist commune in the Rhön Mountains where Lucia often stayed. Like her, they were ambitious, highly educated Neue Frau, or New Women, who had thrived in pre-Nazi Germany. Lucia captured their strength and dynamism but also their idiosyncrasies in seemingly spontaneous photographs that contrasted sharply with her Bauhaus Dessau still lifes and architectural images. She was equally playful in a mid-1925 portrait of László dissolving into laughter while raising a hand toward the camera, as if to stop her from proceeding.

Lucia’s role as the Bauhaus’s unofficial photographer gave her a sense of purpose at a time when she felt increasingly unhappy with her life there and her marriage. “I simply can’t stand it anymore,” she wrote in her diary on May 27, 1927. “I need something that I’m not finding here.” She and László left Dessau and returned to Berlin the following year. It was a welcome change for Lucia, who relished being back in a big, culturally dynamic city. Resuming her photographic experiments, she participated in exhibitions. After she and László separated in 1929, she taught photography at a Berlin art school run by Itten.

By then, Lucia was approaching photography almost as a craft, though not in a conventional sense. She regarded industrialization as an indispensable tenet of modernism, as did her friends. As a result, most Bauhaus teachers and students were committed to designing for serial production, and succeeded in persuading like-minded German companies to mass-manufacture the furniture, ceramics, glassware, textiles, and other products developed at the school. The industrial element of photography was part of its appeal to Lucia, yet the deeply personal nature of her experiments in the darkroom, not least in devising ingenious ways of printing her photographs by hand and of producing images as photograms without recourse to a camera, evokes the intimacy and idiosyncrasy of craftsmanship.

As the Nazi Party gained power in Germany, Lucia’s position as a foreigner, a Jew, and an activist made her increasingly vulnerable. It became untenable in August 1933 when her lover Theodor Neubauer, a Communist politician, was arrested at her home and imprisoned for subversion. (They never met again, and he was executed in February 1945.) Terrified, she fled to Prague to join her family, leaving her possessions in her Berlin apartment except for her archive of prints and 560 glass-plate negatives, which she entrusted to László and his new partner, Sibyl Pietzsch, whom she had befriended.

Over the next few years, Lucia moved to Switzerland, Austria, and France before settling in London, where she combined photography with writing, culminating in 1939 with the publication of her book, A Hundred Years of Photography, one of the first histories of the medium in English. She also continued to work in portraiture by documenting politicians, academics, authors, artists, and other influential Britons, ranging from the peace activist Ruth Fry to the socialite and anti–women’s rights campaigner Margot Asquith.

It would have been easier for Lucia to forge a career in photography after leaving Germany if she’d had her Bauhaus Dessau images. When World War II began, she applied for a US visa, supported by László and Sibyl, who arranged for her to be employed at his recently opened design school in Chicago, and invited her to stay in their home. Yet her application was rejected, so she remained in London. After the war ended in 1945, she asked László to return her archive. He explained that he had given it to Gropius for safekeeping before he and Sibyl left Berlin. Unbeknownst to László, Gropius had shipped it to the United States with other Bauhaus artifacts in 1937, when he began an academic career at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Courtesy Galerie Derda, Berlin

All works by Lucia Moholy © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. All László Moholy-Nagy works © Estate of László Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Given the turbulence of the time, neither man behaved unreasonably. The problem was that Gropius then used her “Bauhaus photographs” in numerous projects, without asking her permission or crediting her. He made the same omissions when releasing her images for use by others. When Lucia wrote asking him to send prints for her to screen in a lecture, he advised her to contact a British architecture journal instead. She then discovered that he was also storing her negatives, which, until then, she believed had been destroyed, and demanded their return with compensation, eventually hiring the lawyers described in Ise Gropius’s letter to help her. In 1957, after three years of fraught negotiations, Lucia recovered most but not all of them. Two years later, she left London for Switzerland, where she lived until her death in 1989, writing on art and the Bauhaus.

Plucky, resourceful, and talented, Lucia Moholy was a remarkable woman who led an extraordinary life. Why is her work better known than she is? A prime factor was misogyny. Like all gutsy Neue Frau, she faced gender discrimination at every turn. She had been lucky in marrying such an enlightened man as László, but her early photographs were routinely misattributed to him. Like him and many of their friends, she faced repeated struggles to rebuild her life in various countries during the turbulence of Nazism and World War II, but for her, those challenges were aggravated by anti-Semitism. She was also unlucky in facing such a powerful, well-connected opponent as Gropius. Lucia emerged victorious, but only after a long, painful battle. A cruel irony is that had the archive remained in his Berlin house, as László and Sibyl intended, it would have been destroyed when the building was bombed during World War II. And had Lucia kept it after leaving Berlin, it would have suffered the same fate, as her first London apartment was ravaged by fire during a 1940 air raid. In either scenario, those precious Bauhaus photographs would have been lost.

This essay originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue.”