Essays

The Women Photographers Who Consider the Dynamics of Being Seen

At a moment when women are increasingly losing control over their own bodies, can self-representation become a form of resistance?

© the artist and courtesy Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna

Sometime around 1987, at the age of seven, I got caught looking. I was curled up on the sofa after school, watching MTV with the volume down low. The channel was all but verboten in our house at the time. At some point, the video for Madonna’s “Open Your Heart” came on, featuring the singer herself as an exotic dancer who—spoiler alert!—ultimately escapes from the peep-show theater in which she performs. I was immediately entranced. I turned the volume lower still, ashamed but unable to avert my eyes. And then, just as Madonna pranced across the screen clad in a black satin bustier complete with gold nipple caps and tassels, my mother walked into the living room. “What are you watching?” she asked, somewhat dismayed to find me mesmerized by the sexualized performance playing out before us. Before I could change the channel, she turned off the TV and proceeded to the kitchen.

Decades later, I still love this music video, which seems rather tame in hindsight. Released amid the Reagan administration’s antiporn campaign, the video was banned by a few channels and became a lightning rod for feminist debate. Some critics viewed Madonna’s portrayal of a sexualized woman subjected to the male gaze as retrograde. Others believed the video helped to destabilize the hierarchy of the gaze, with Madonna unafraid to return the lascivious stare of unsightly, sleazy male patrons. Perhaps the divided opinions in my house mirrored this split among critics. Looking back now, I wonder about my mother’s response. Did she believe I was too young to view anything with an erotic charge or subtext? Should a child not be allowed to conceive of a woman as a sexualized figure, or even as an object of desire? And why had I felt ashamed? Was there some corollary between me and the innocent “presexual” boy in the video, who lingers outside the theater and plays one-way peekaboo with a nude female on a pinup poster until Madonna emerges and skips off with him into the sunset?

This line of inquiry ultimately invites a larger question: Who gets permission to look?

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

I found myself asking this same question in 2016, upon my first encounter with the New York–based artist Talia Chetrit’s work. Shown as part of the AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), in Toronto, the opening wall displayed a provocative diptych: at left, an image of Chetrit’s camera on a tripod held between her bare legs, suggestively angled toward her crotch (which was presumably exposed, but not included in the frame); at right, an image of her lower body, naked from the waist down except for a pair of “invisible” jeans (effectively a waistband with the seams of the excised denim pant legs still attached). I watched the room to see how other visitors were engaging with her photographs, feeling as if I’d unwittingly stumbled into a video store that only stocked adult films. No one else appeared fazed.

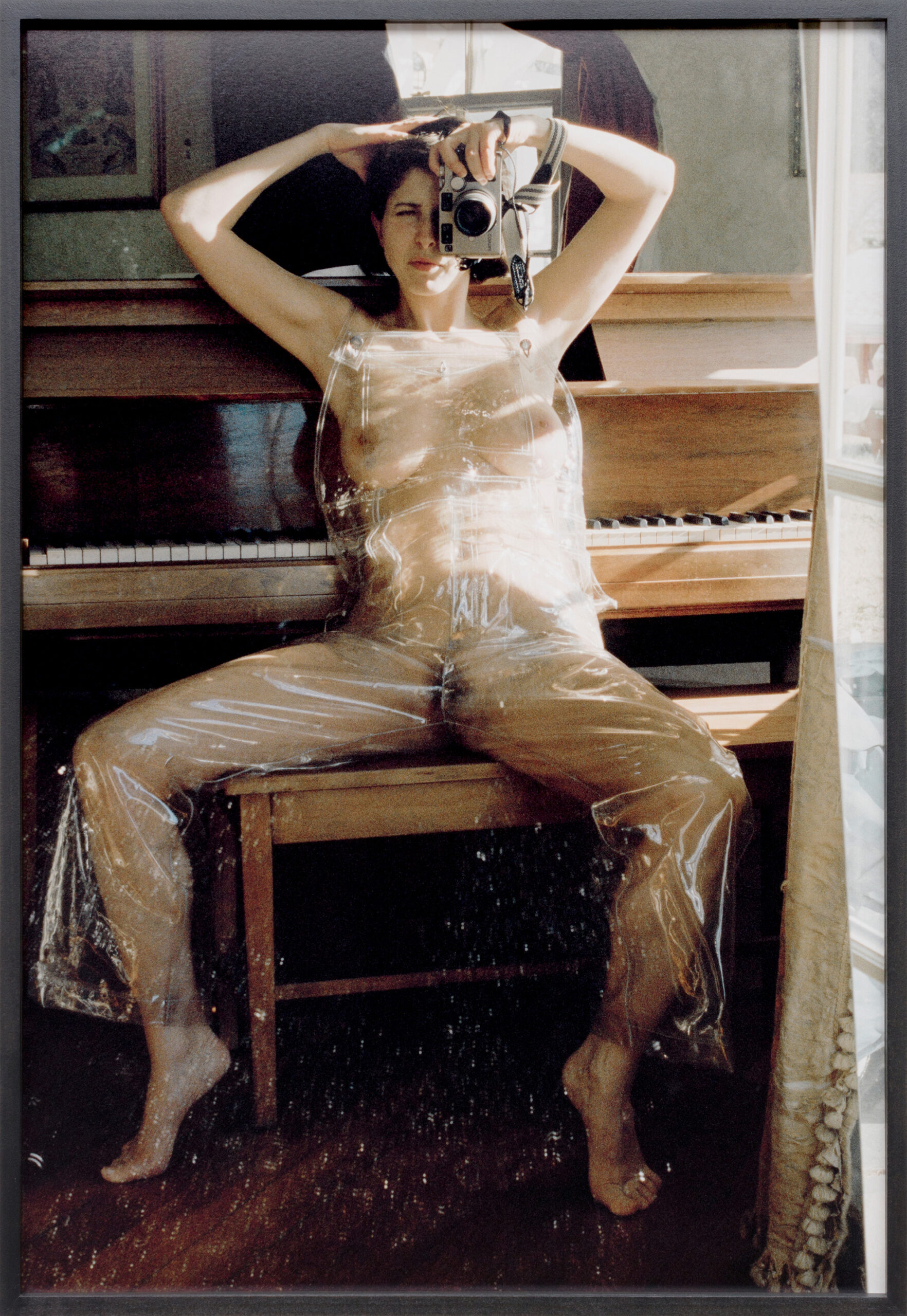

Another photograph by Chetrit, Plastic Nude (2016), which I came across later in her 2019 book Showcaller, further complicates the question at hand. In this image, Chetrit photographed herself from head to toe with the aid of a mirror—which, in its reflection, reveals that she is dressed in transparent overalls. While Chetrit’s see-through garment leaves virtually nothing to the imagination, it’s not exactly titillating by default. Perhaps this image is an evocation of the striptease, which, as Roland Barthes characterized it, “is based on a contradiction: Woman is desexualized at the very moment when she is stripped naked.” Then again, is Chetrit nude? As she leans back against a piano, her plastic-wrapped torso and legs all but open to be viewed, I can’t help but be reminded of the beguiling woman dressed deceptively in a flesh-colored body stocking that E. J. Bellocq photographed a century earlier. In each case, the viewer must look closely to determine if the nudity is an illusion.

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Courtesy the artist; kaufmann repetto, New York; Hannah Hoffmann Gallery, Los Angeles; and Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf

In Plastic Nude, Chetrit’s body remains encased in some kind of PVC layer, akin to a work of art displayed behind glass. Her outfit ultimately says: You can look, but you can’t touch. With this work Chetrit embodies the oft-cited idea that the film theorist Laura Mulvey described in her groundbreaking 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”: “The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.” And yet, holding a camera in front of her face, she simultaneously reminds the viewer that she—the artist and the sitter—participates in the act of looking while presenting herself as the sight to be looked at.

Since my visit to the AGO, I have noticed something of a vogue among a small but sharp crop of contemporary photographers—all of them women born within a decade of forty-one-year-old Chetrit—for whom self-representation functions as an exercise in “to-be-looked-at-ness.” On the face of things, this is not new. Within the history of photography, there is a rich tradition, particularly in the West, of women photographers’ work disrupting the structures of looking. As the noted art historian Griselda Pollock wrote in 1982, arguing for feminist rethinkings of art history, “creativity has been appropriated as an ideological component of masculinity while femininity has been constructed as man’s and, therefore, the artist’s negative.” Looking across the twentieth century, one can find interwar women photographers such as Gertrud Arndt and Claude Cahun, who made pictures of themselves that countered conventional and patriarchal ways of seeing women. In the 1970s, a particularly fertile moment in this history, feminist practitioners like Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke generated self-representational work that further complicated the objectification of women and addressed what Pollock referred to as “the signification of woman as body and as sexual.” Emerging in their wake in the 1980s, another wave of groundbreaking women photographers—Laura Aguilar, Jeanne Dunning, and Catherine Opie among them—made work depicting bodies (their own) that further deviated from art-historical norms and contemporary conventions of beauty and femininity.

Just as there’s often a need for women to talk to one another for their voices to be heard, there’s an enduring need for us to see each other, too, in all our multiple, complicated selves.

Chetrit and other midcareer photographers consciously deploying self-representational forms today are certainly inspired and informed by this history. Some were even formally educated by women who helped to shape it. But beyond their placement, chronologically speaking, as part of its continuum, how do they relate to the tradition of female photographic self-representation? And how does this seeming trend of soliciting, welcoming, and approving “to-be-looked-at-ness” relate to the present moment in which it unfolds?

By the 1980s, several decades before this latest wave of practitioners began their careers, feminist issues and theory had reached the mainstream, and criticism had strengthened its focus on the problem of “woman-as-image,” as identified by the art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau. With discussion around the representational politics of gender and the power relations of looking already well underway, younger contemporary photographers have entered into the conversation midstream, arriving with different agendas.

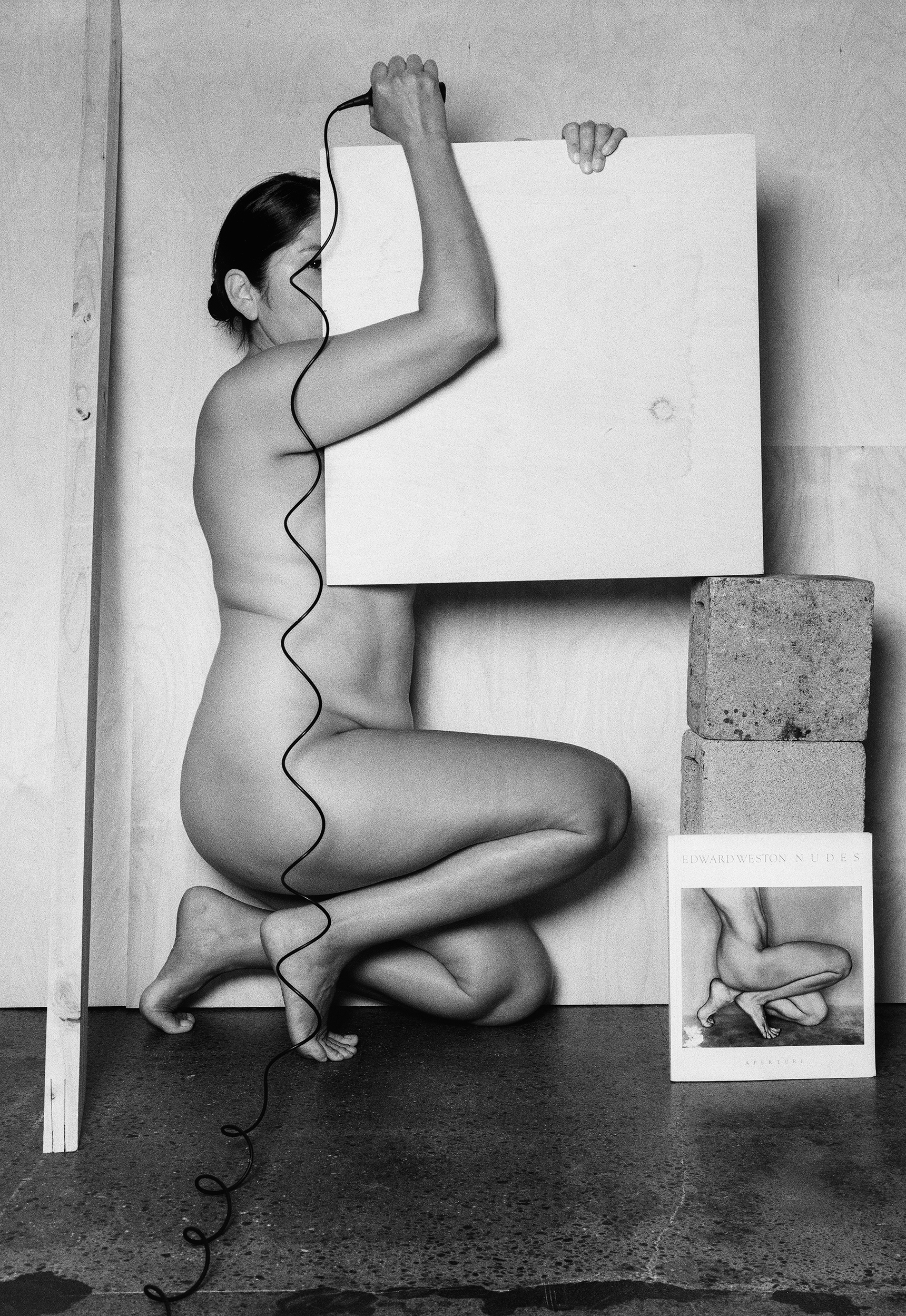

For some, inclusion in the canon of photography and the visibility it brings—the understanding that their bodies will most certainly be looked at—is part and parcel of the impulse to photograph oneself. The Peru-born, Oregon-based photographer Tarrah Krajnak models this approach in her 2020 series Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, wherein she poses in the guise of Edward Weston’s female sitters but, given her Latin American background, challenges what she describes as “the ideal of white female beauty central to Weston’s work and its historical appreciation.” Krajnak incorporates direct references to her predecessors, such as Weston’s one-time wife and model Charis Wilson, by including Weston’s images of them within the scenes she stages, ultimately generating distorted mise en abymes.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

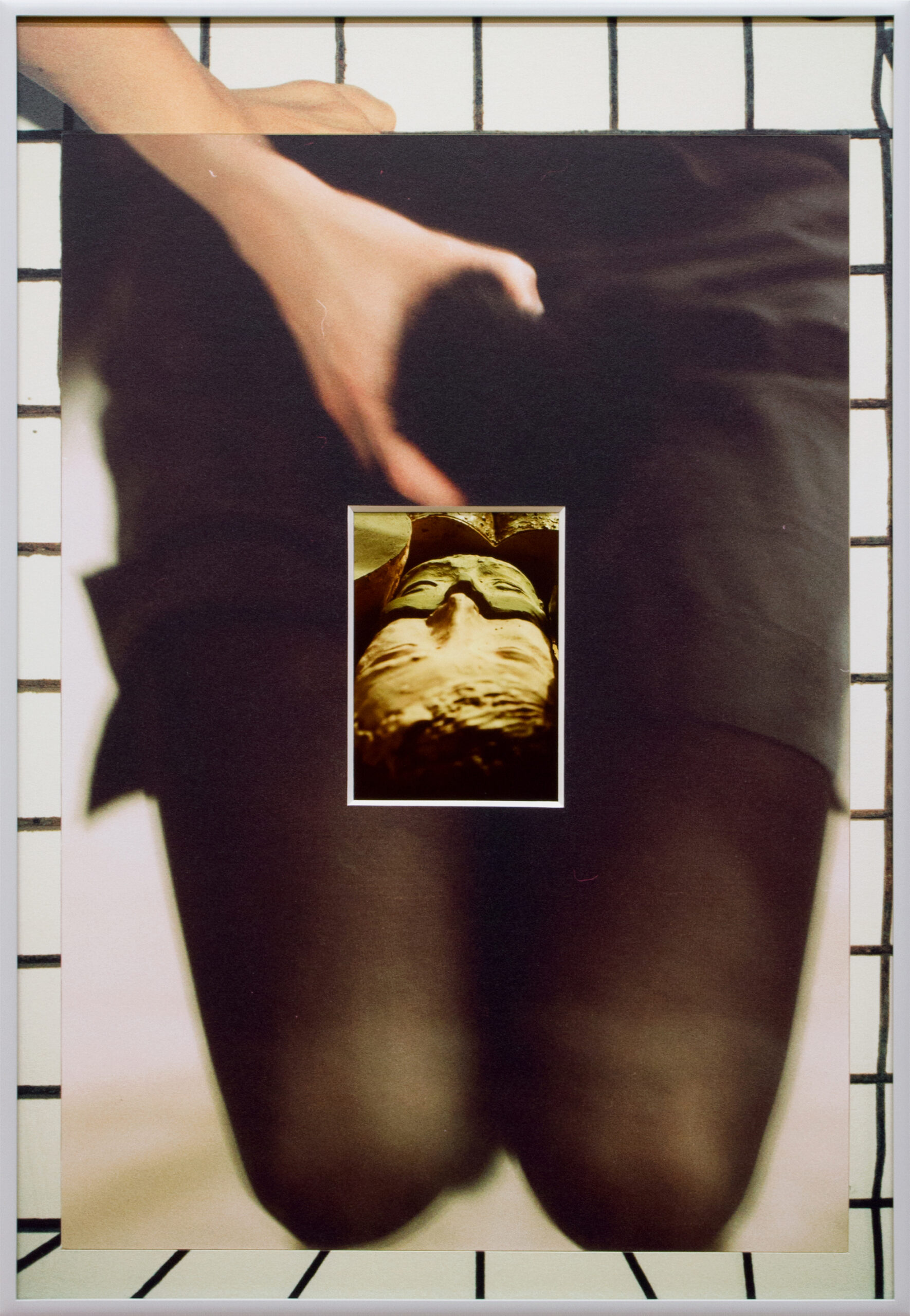

Nydia Blas, raised in the predominantly white city of Ithaca, New York, employs photography as a means for creating spaces that celebrate multiracial bodies like hers, which historically have been discouraged if not prevented from representing themselves. In a photograph of her midsection and upper thighs, titled My Body Has Been Colonized (2022), Blas reveals a tattoo in Spanish—the language of her father, which she can’t speak fluently—and stretch marks. She subtly obscures the latter while maintaining her modesty with a handkerchief covered in flowers native to Panama, her father’s birthplace. “Is it possible to reclaim something like sexuality in a photograph where you don’t have clothes on?” Blas asked when I spoke with her recently. “How can you still maintain power?” She admits that while she doesn’t have an answer, there is strength in reclaiming something for oneself in self-representation, in part because, as any photographer knows, it’s devilishly difficult to photograph yourself.

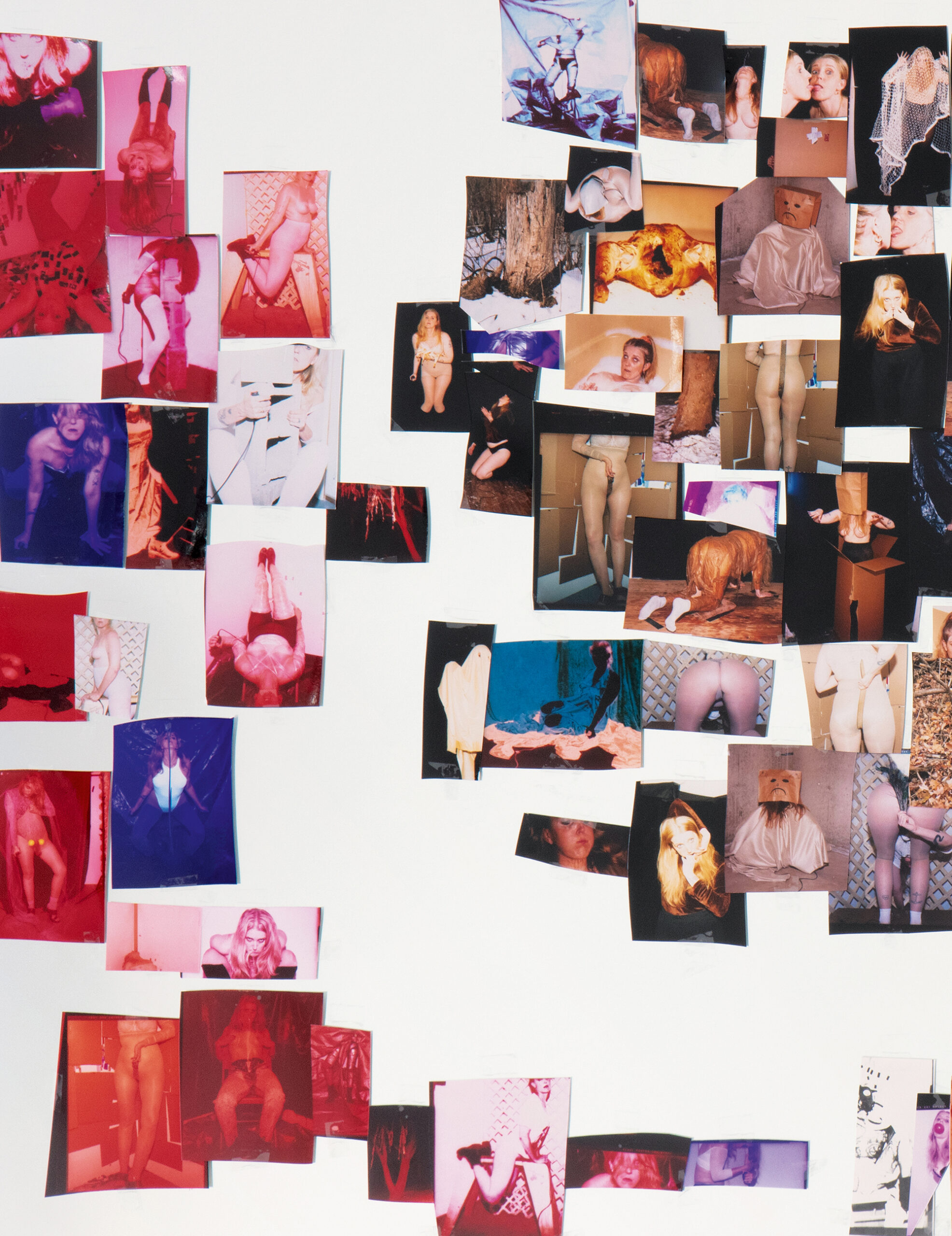

Two other photographers, Iiu Susiraja and Whitney Hubbs, despite the marked differences in their work, both mobilize the trope of the feminine pinup and its associative baggage, employing humor to neutralize it. Hubbs, born in 1977 and based in Syracuse, New York, mocks her own ability to adapt this fetish, partly given her age. Wearing protective knee pads while balancing a watermelon on her back or reclining topless while supported by a chair pad, Hubbs’s stagings evoke something like the grotesque or carnivalesque. In the case of Susiraja, absurd props, occasional bruises, and a deadpan style confound conventional expectations around viewing an image of a seminude body, if not to simply desire, consume, or covet it. According to Susiraja, who lives and works in Turku, Finland, the prospect of acceptance partly fuels the public dissemination of her photographs. In a 2022 interview, she likened her interest in seeking approval through self-representation to how people utilize social media: “I believe when you put self-portraits to Instagram, you look for acceptance and love.”

© and courtesy the artist

How should we think about the apparent increase in self-representational tactics used by women artists today? Can it be seen as a consequence of selfie culture and its aspirational, branded aesthetic? It bears noting that in the past ten years, the decade during which much of the work discussed here was made, social media flourished. Its platforms produced, disseminated, and censored notions of femininity and masculinity, as well as sex and gender. Around 2013, gender-based double standards that permitted censorship of female breasts on social media prompted an advocacy campaign called Free the Nipple. In her series The Greece Piece, from 2019, the Dominican-French photographer Karla Hiraldo Voleau gives a nod to these policies, making self-portraits where she exposes her breasts, which she then covers up with tape on her prints. Gender-based exclusionary practices, likewise, informed the photographs in her contemporaneous project Hola Mi Amol and its eponymous book, which show Voleau close-up and clothed alongside her hypothetical male paramours in the Dominican Republic, whose bodies almost always appear seminude or nude. By way of explaining her motivation to make the project, Voleau asks, “Why couldn’t women stare, gaze, observe, desire, objectify, and look at men the same way they were looked at?”

Despite her best efforts to shift the power balance between the seer and the sight to be seen, Voleau understands the limitations of her strategy. She remains “woman-as-image” to some observers, acknowledging as much in Hola Mi Amol. The book closes with an image of her lying recumbent in bed, fully clothed, staring back at the reader. Beneath the photograph, she poses the question: “Have I been transformed into the character I was pretending to be?”

In The Desire to Desire, a 1987 book about Hollywood films and female spectatorship, Mary Ann Doane reinforces this sort of conclusion. “It can never be enough simply to reverse sexual roles or to produce positive or empowered images of the woman,” she writes. Photographers Tokyo Rumando and Sophie Thun, another unlikely pair, share an ability to recognize this limitation. Both assume the existence of a putative male gaze whose powers they mock, and try to undermine by assuming the position of the spectator (presumed a man) within their images.

Tokyo Rumando, Orphée, K-1, 2014

© the artist and courtesy Zen Foto Gallery

An erstwhile model for the provocateur Nobuyoshi Araki, widely known (and recently publicly derided) for his explicit depictions of women, the Tokyo-based photographer Rumando reprises the position of subject in Orphée, a series published in 2014. Here, though, Rumando takes control of her representation. She depicts herself beside a round mirror—a proxy for her camera’s lens—that doesn’t directly reflect her likeness. Instead, the mirror acts as a portal that presents another version of Rumando (she plays twenty-six unnamed characters in the mirror, some of them styled to resemble famous figures such as Marilyn Monroe or the writer Yukio Mishima) to enact fantasies, desires, and memories. In an interview published in 2017, Rumando divulged that “the mirror and I are not facing each other directly, which means that the encounter is not a confrontation. Instead, it’s like I’m watching from afar.” Assuming the role of spectator within the composition, she attempts to displace or redirect the gaze of additional viewers who exist beyond the frame. Between these various depictions of Rumando, which collectively function like the reflections in a funhouse mirror, where are we supposed to direct our attention?

Based in Vienna, Thun parlays jobs assisting male artists by utilizing the hotel rooms she occupies during those gigs to create her ongoing series After Hours. This premise allows Thun to unpack notions of “hierarchy and interdependence, because these artists depend on me in a technical capacity, and I am dependent on them financially,” she says. Turning these rooms into makeshift studios at night, she photographs herself naked and, most crucially, often collages her pictures so that she appears twice in the composition, usually in positions that suggest she’s having sex with herself. Like nearly all the other photographers mentioned here, Thun uses a film camera and employs a cable release to photograph herself. The visibility of her devices is essential, communicating her technical skill and, by association, her authority: this is what knowledge and control look like. They are active, as is her body, which refuses to play the art-historical part of passive object of desire. As viewers survey her work, they are confronted by Thun and her double, who address Thun’s camera with an unflinching gaze. But to invoke Doane again: Is that enough of a power play to expose or disturb the status quo?

Courtesy the artist

© the artist and courtesy M+B, Los Angeles

What if the quality of work that invites looking and commands a certain “to-be-looked-at-ness” also actively chafes against the instinct to gender the body? What if the bodily form in the photograph defies identification within the categories of male, female, or nonbinary? The photographs of the Chicago-based artist B. Ingrid Olson—who identifies as female but appreciates the mystery and possibility of androgyny afforded by her first initial—explores this terrain. In an interview on the podcast Modern Art Notes, she confesses to “making images that allow you to see yourself in the image or make yourself more aware of being a body in front of an image.” But she’s resistant to labeling her work as self-portraiture; indeed, as Solomon-Godeau has noted, self-representation is not always self-portraiture. Olson’s face never appears in her pictures, while the rest of her figure appears so fragmented as to become defamiliarized and nearly inscrutable; it’s difficult to pinpoint what crevice, orifice, or limb she has photographed. To understand what you’re looking at, you have to keep looking.

“It’s okay to look and like looking,” Whitney Hubbs remarked after I told her about my long-ago moment with the Madonna video. “I had a similar reaction while watching [the 1983 film] Flashdance. It was arousing.” It strikes me that this admission reflects another potential rationale behind the rash of self-representational photographs that Hubbs and others are making today: just as there’s often a need for women to talk to one another for their voices to be heard, there’s an enduring need for us to see each other, too, in all our multiple, complicated selves. In a political climate when women are increasingly losing control over their own bodies, such self-made forms of visibility fulfill a particularly useful function. They encourage what the authors of Caught Looking, a book on feminism and pornography, identified as “free discussion of sexuality and its representation [which] is essential to our feminist vision.” They reveal what we otherwise ingest without thinking. They make us want to keep looking.

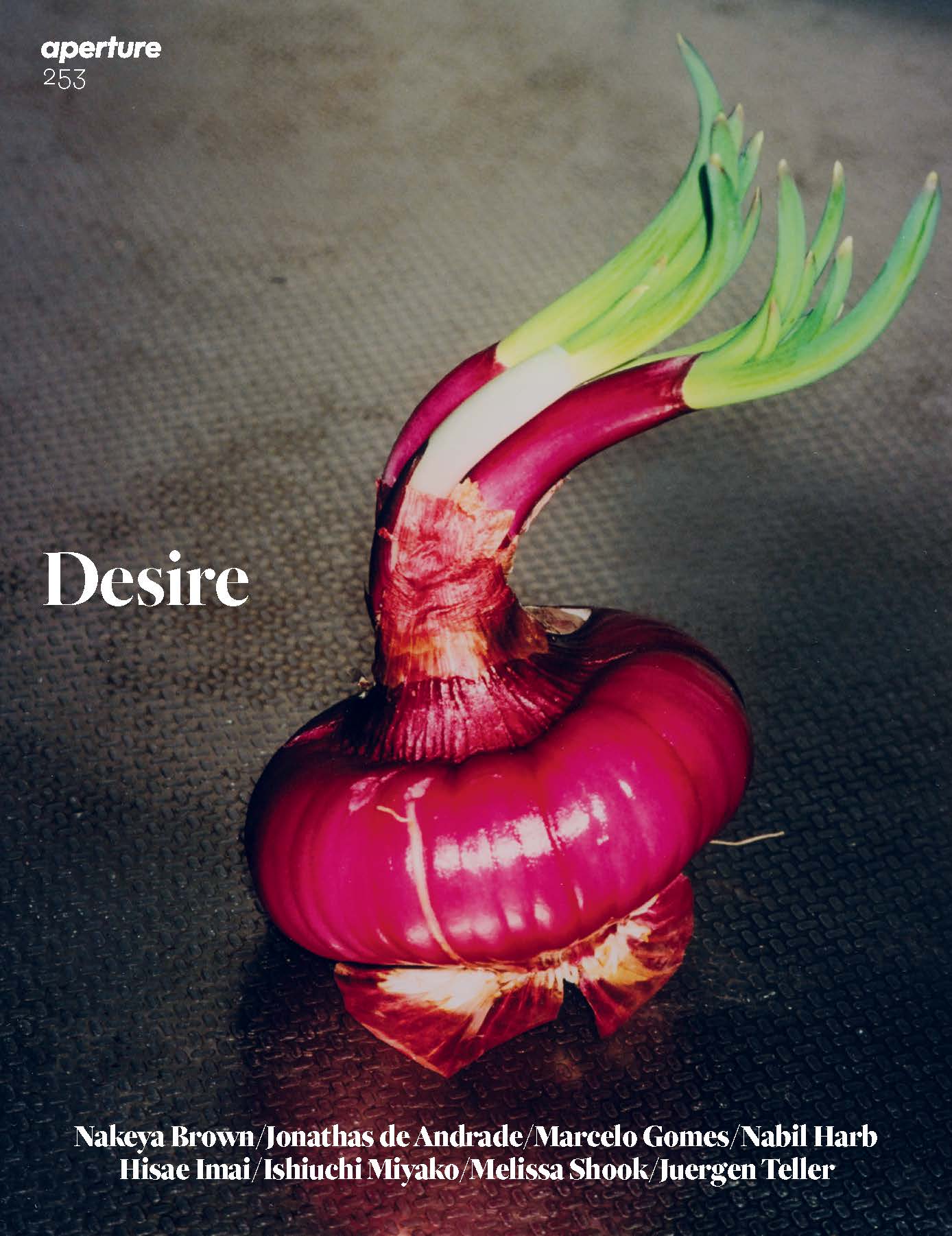

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire.”