Interviews

Tracing Africa’s Photographic History in Books

The curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo speaks about Africa’s political transformations and the role of publishing in shaping artistic knowledge.

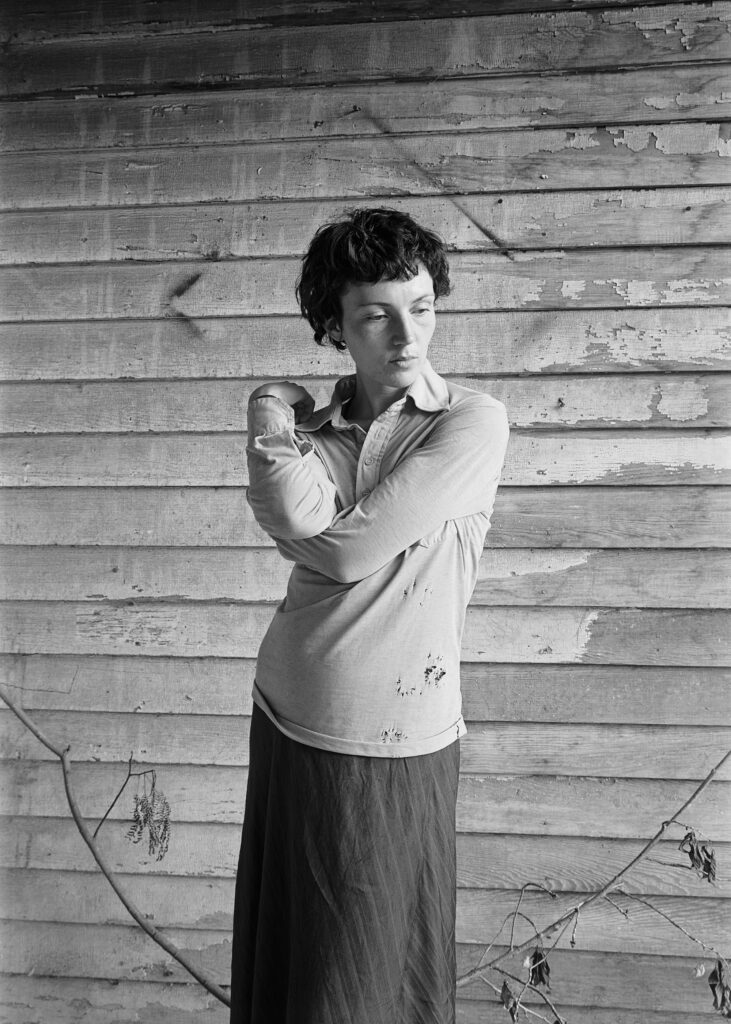

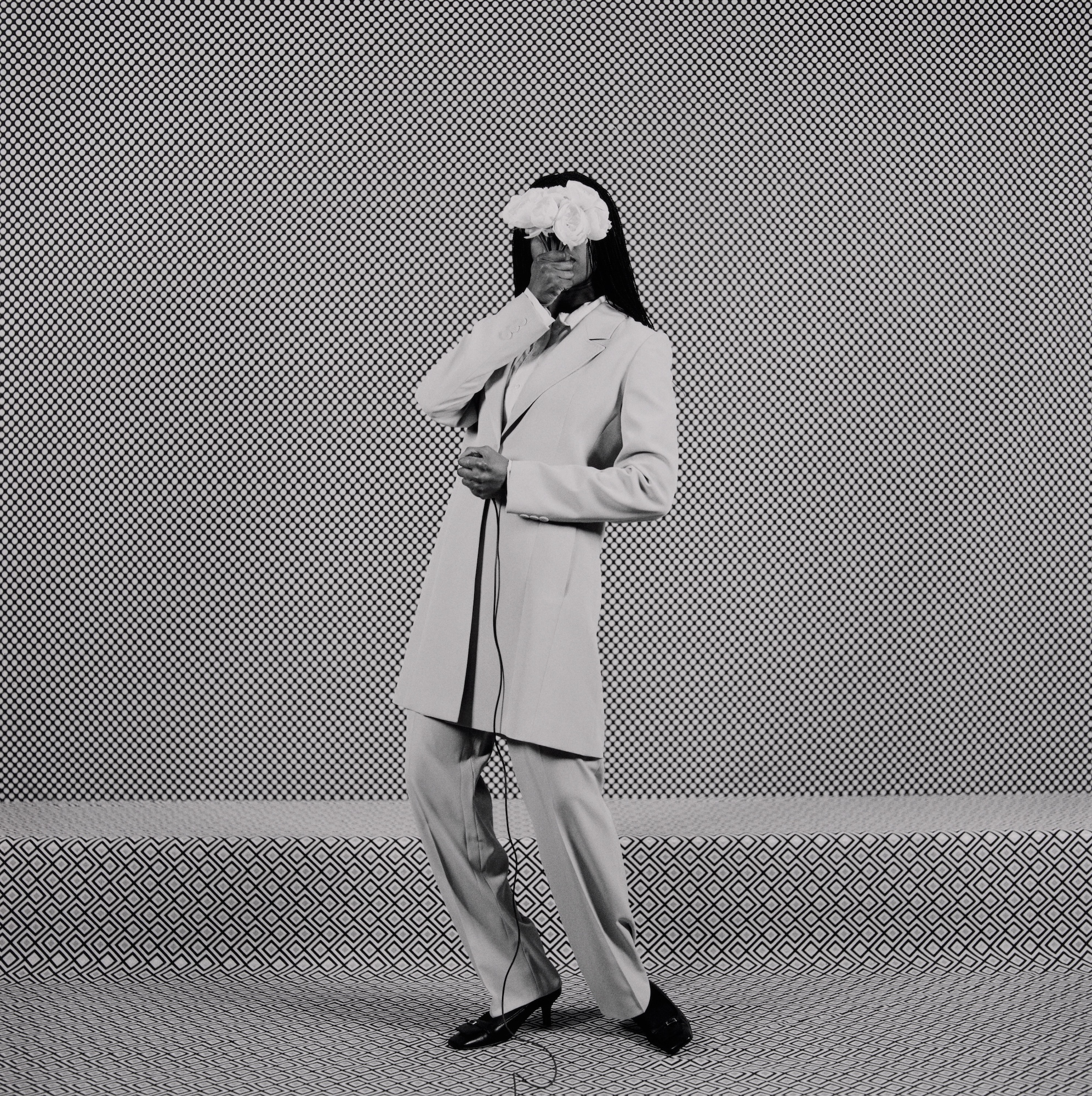

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

In the 1990s, a group of African writers and curators began to stage exhibitions that would inspire a surge of world-wide interest in photography from the continent. Their goal was to turn away from the “ethnographic lens”—the news imagery of famine and war that dominated media coverage of Africa—in favor of the artistic voices that defined African photography, from the gracious studio portraiture of midcentury Mali to the poetic, long-form reportage of David Goldblatt and Santu Mofokeng in South Africa.

The late curator Okwui Enwezor, who cofounded Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, once said that publishing is a space “in which thinking could be elaborated.” Enwezor produced some of the era’s totemic exhibitions and catalogs, while the curators Bisi Silva and Koyo Kouoh built institutions for contemporary art—Center for Contemporary Art (CCA) in Lagos and RAW Material Company in Dakar, respectively—influencing a new generation including Oluremi C. Onabanjo, now a curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

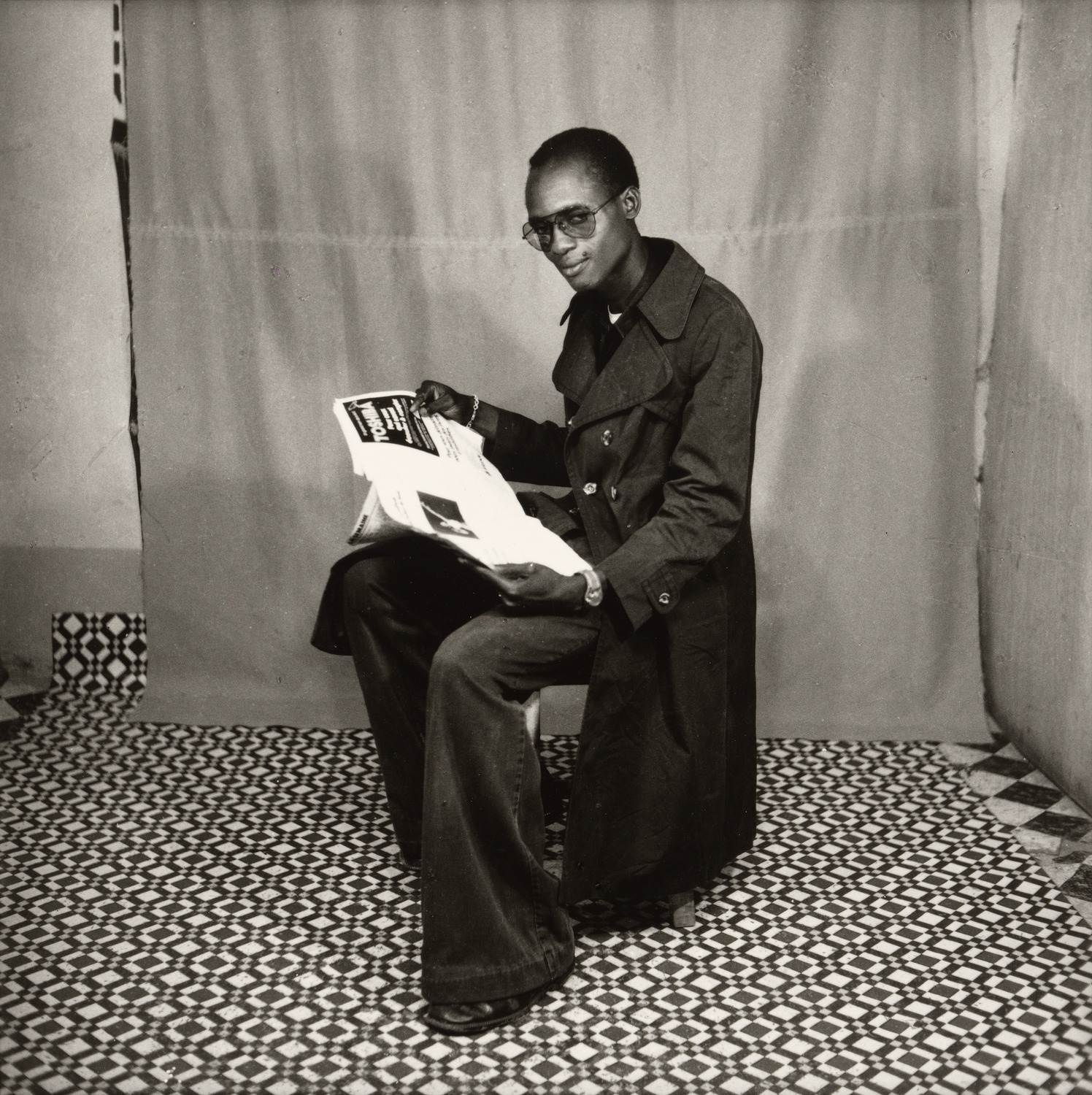

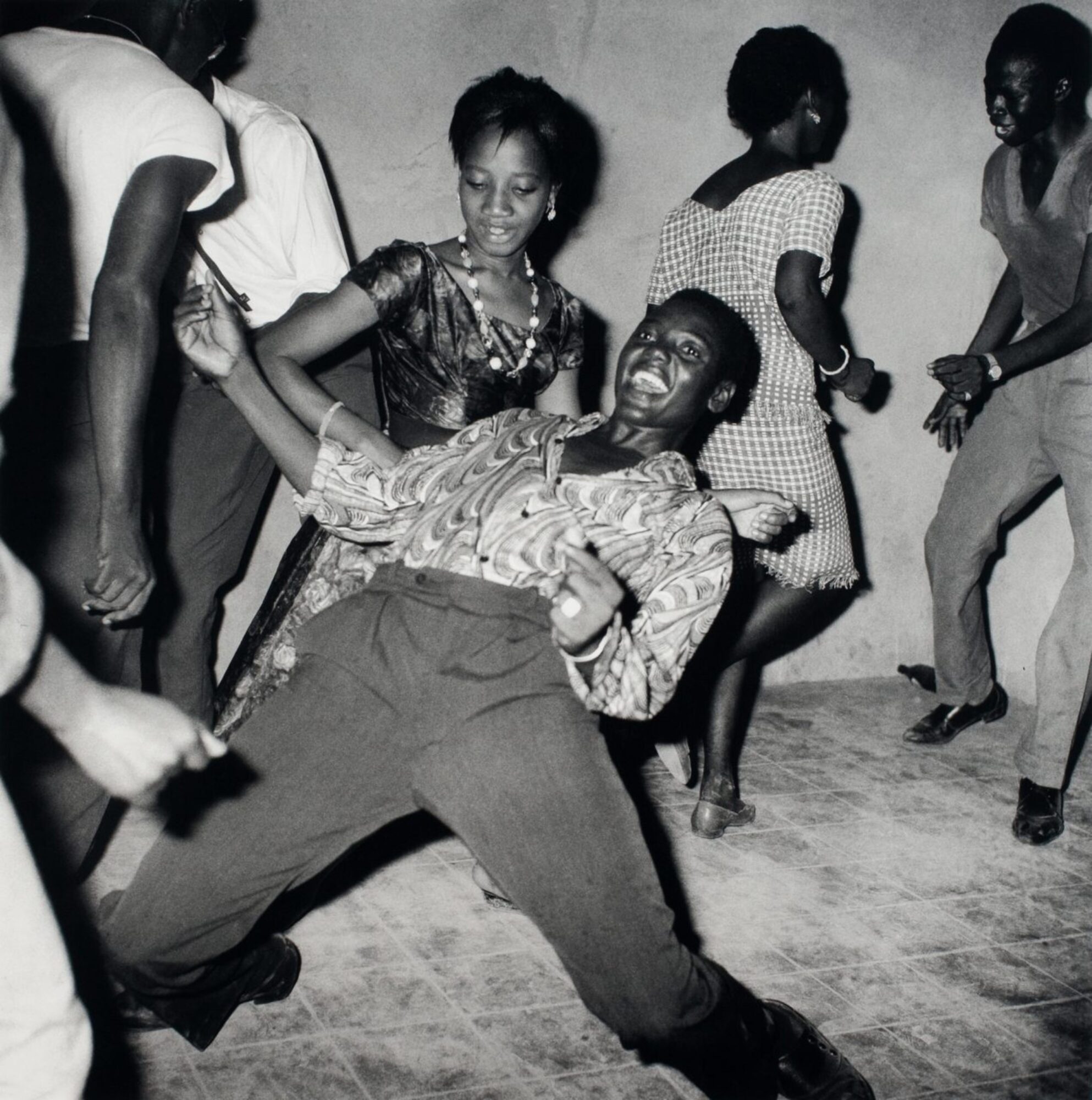

Onabanjo’s new exhibition Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination returns to a critical era of photographic history, linking the postcolonial transformations of the 1960s and 1970s to the US civil rights movement through works by photographers such as James Barnor, Kwame Brathwaite, Samuel Fosso, and Sanlé Sory. Photobooks, Onabanjo explained in this recent conversation, are at the center of the exhibition, encouraging viewers to see how publishing has been vital to the production of artistic knowledge.

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

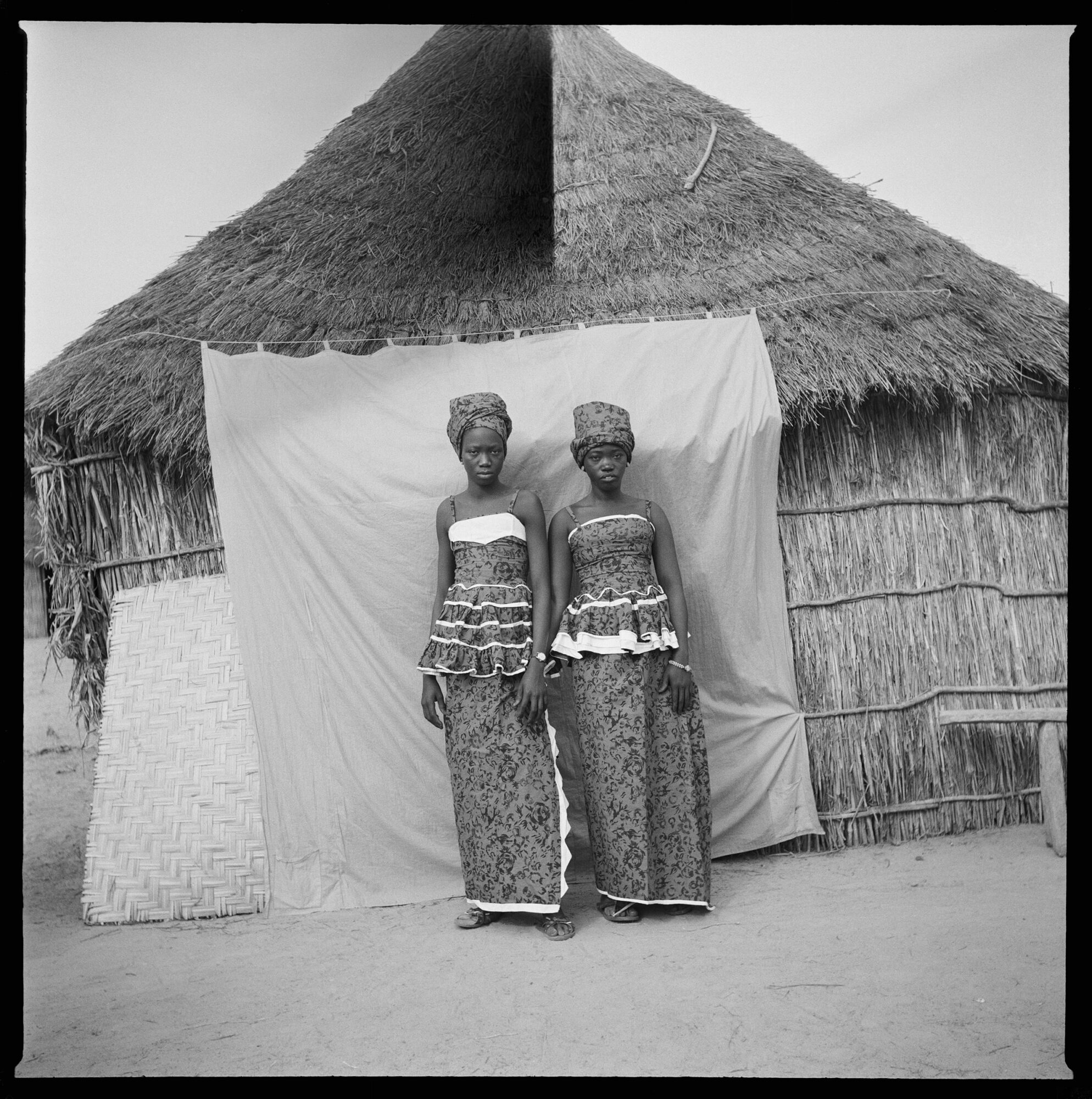

© Oumar Ka Estate and courtesy Axis Gallery, NY

Brendan Embser: Your exhibition at MoMA references the 1994 book by V. Y. Mudimbe, The Idea of Africa. But I gather from the plurality of your title, Ideas of Africa, that you’re indicating that there’s going to be multiple points of entry both to history and photographic style.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: I wanted to entice people to consider a show of midcentury Western and Central African portrait photography, in and out of the studio, through the vector of imagination—and to grapple with the form’s ongoing legacy and force as a creative mechanism.

The potential of political imagination has been somewhat effaced from contemporary discourse around portrait photography on the continent, even though it’s a crucial point for comprehending the genre. The so-called golden age of African photographic portraiture takes root during the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s—a moment of significant upheaval on the continent and across the globe.

I particularly wanted viewers who are informed by a history of the US civil rights movement to recognize that those forms of resistance were built on internationalist modes of solidarity.

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Embser: There’s a reading room as part of the exhibition. How do photobooks fit into the project?

Onabanjo: The reading room came out of an encounter during a studio visit in Paris with the artistic collective Air Afrique, whose name pays homage to the defunct Pan African Airlines that ran from 1961 until 2002 and had service throughout Francophone West Africa, also with routes to London, Paris, and New York. The airline produced an in-flight magazine throughout its entire run titled Balafon—a place where political ideas circulated through coverage of film, arts festivals, and profiles of Malick Sidibé on the front cover.

Being mobile was such a key point around an internationalist claim for people in Africa during the ’60s and onward; to be in relation to liberatory ideas that exceeded the nation state, you needed to be able to envision exceeding it yourself.

I’m trying to embrace that spirit of the Air Afrique collective. They’ve now produced two issues of their own magazine, which will be available in the reading room alongside books that have informed the entire structure of this exhibition.

Embser: We’re in an era of republishing the classics, you could say, from Aperture’s reissue of Ernest Cole’s 1967 House of Bondage to Steidl’s reissues of books by the late South African photographer David Goldblatt. For a long time, House of Bondage was nearly impossible to find. You’ve called it a “fugitive” book. What did you mean by that?

Onabanjo: For almost seven years, Cole furtively took the pictures that formed the photographic base of the project—relentlessly documenting every aspect of life under apartheid in South Africa. In 1966, he fled the country at the age of twenty-six under the guise of a pilgrimage to Lourdes—prints and layout sheets in hand. He knew that a book with this kind of undeniable force could only be made in exile.

My own first edition of House of Bondage is fugitive. I pinched a copy from my father’s library when we were living in Johannesburg in the 2000s, which he had gotten from a secondhand bookstore in the city’s central business district. For decades prior, Cole’s work was banned in the country, and many South African photographers could only encounter that book in David Goldblatt’s library.

I like this idea of knowledge production being something fugitive that exceeds linear or expected routes of transmission, and I think that’s extremely important to photography in its history, and particularly photography’s history on the continent.

Cover and spread from Ernest Cole, House of Bondage (Aperture, 2022)

Embser: House of Bondage was published for a foreign audience and meant as an activist document, right?

Onabanjo: Absolutely. The idea was to open the eyes of the world to the horrors of apartheid within South Africa. I think the book continues to resonate today, well beyond its intended or expected recipient or moment. The second edition really makes proof of that.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Embser: Goldblatt’s first books were published in the 1970s and ’80s. They have the appearance of beautiful photography books but not necessarily artist books. On the Mines included an essay by Nadine Gordimer, the novelist who would go on to win the Nobel Prize. They’re like a record of Goldblatt’s work as a documentarian who was narrating a particular experience through words and pictures. Now, the books are republished by Steidl and marketed as art books and seen in a much more contemporary art-publishing space.

Onabanjo: Histories of circulation tell you a great deal about what the photographer’s existing universe was. Goldblatt’s early books were published in apartheid-era South Africa. But by 2003, when he publishes Particulars, he was represented by Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris, and his work had already been the subject of a solo exhibition at MoMA, organized by Susan Kismaric, in 1998, so his photography was circulating in fine-art contexts internationally.

© the artist

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Embser: Santu Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950 (2012) is also an important book, and a record of a slideshow first shown at the Johannesburg Biennale in 1997. In that respect, the book is like Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency in that it’s a record of an installation experience—a slideshow—that would otherwise be evanescent.

Onabanjo: It’s profoundly important. The Black Photo Album includes eighty slides, a combination of text and studio portraits of South Africans drawn mostly from private family collections. It’s a watershed work for a history of conceptual photography—it anticipates the archival turn in some ways. Unfortunately, it’s currently out of print, but hopefully not for long.

It’s just as important to think from Dakar as it is to think of Dakar.

Embser: Steidl later published Stories (2019), an enormous compendium of Mofokeng’s photography comprising eighteen books and clocking in at 1,046 pages—and with an equally large price tag at $385.

Onabanjo: Yes, it’s an amazing set of booklets that speaks to this photographer’s intrepid vision, his risk-taking sensibilities, the expansiveness of his approach. It’s so beautifully printed, and it has incredible writing from Santu. But again, one thinks around limits of circulation for something of that form: Who’s going to see this? Who can afford this? How are they going to get ahold of it? How are they going to benefit from this vision?

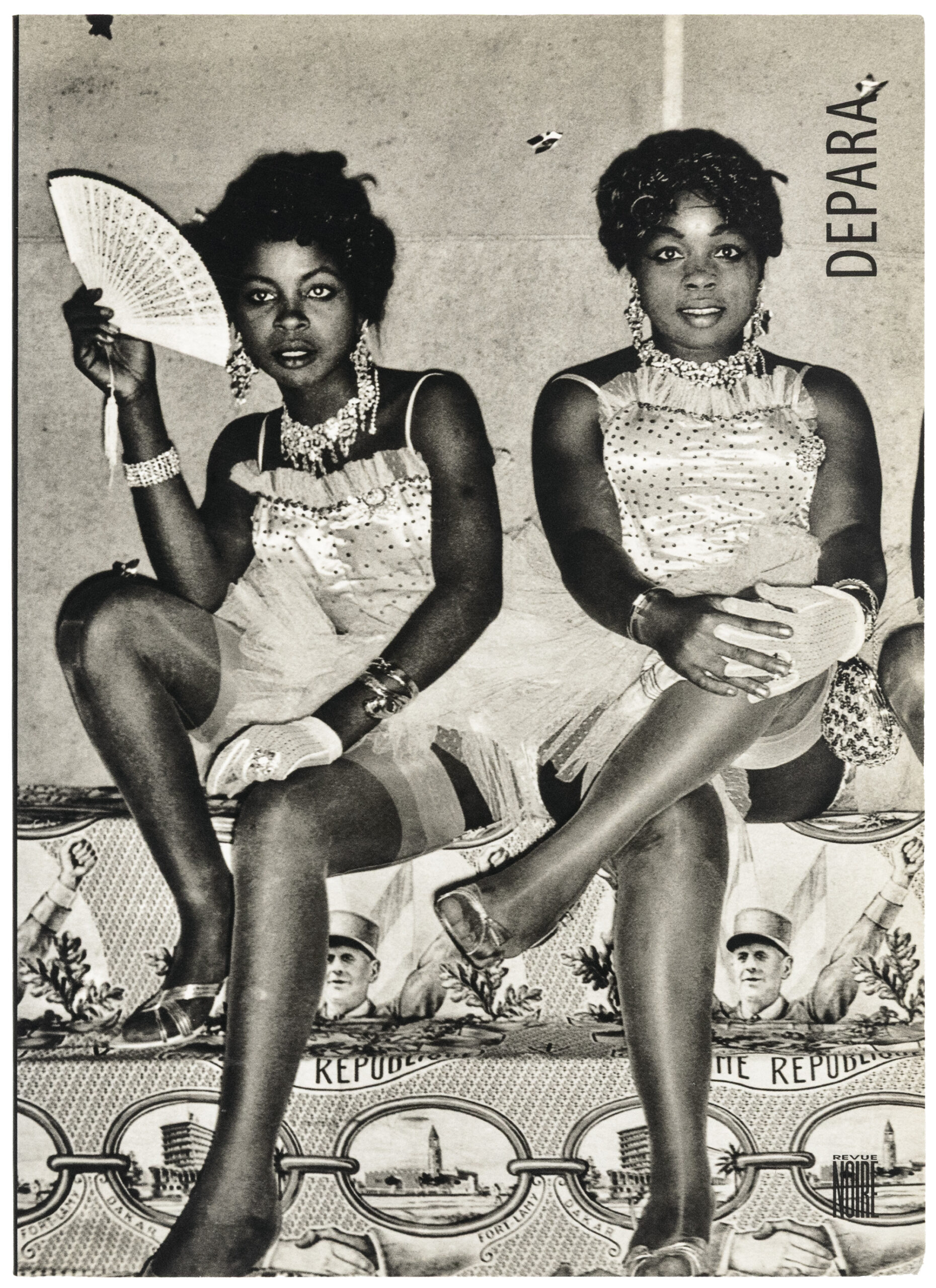

Embser: I want to get your perspective about publishing platforms focused on African art and photography. Revue Noire, based in Paris, was instrumental in publishing small, accessible books like the famous Photo Poche series, which provided excellent ways of learning about Samuel Fosso, Jean Depara, Mama Casset, and others. For a long time, Revue Noire’s Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (1999) was like the white pages—if you needed to find anything about someone, probably it was going to be in that book.

Onabanjo: Yes, absolutely true. It was about capacity building. You have these beautiful plates, but you also have artist biographies, you have listings, you have all these contributors. From Deborah Willis to Emanoel Araújo, the Revue Noire team was uniquely gifted in identifying key figures across the globe who could give the reader an entry point for a bevy of photographers who you must know in every corner of space surrounding the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York/the Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Embser: Its utility function was massive.

Onabanjo: Totally.

Embser: RAW Material, CCA, and Fourthwall Books in South Africa have all published photobooks and critical readers on art and photography, each in their own style. Again, they were celebrating artists but filling an important space for criticism and art history.

Onabanjo: I feel like the subtheme of our entire conversation has been the importance of building capacity and setting up important foundations for people to continue to work. People such as Bisi Silva at CCA and Koyo Kouoh at RAW Material embodied what it meant to put these commitments into practice on an infrastructural level. For her Condition Report symposia, Kouoh had these amazing events where she would bring together a number of different intellectuals, arts administrators, and curators from across the continent underneath one specific theme, idea, or set of positions for people to talk about what they were facing.

These events allowed people to come together and learn from each other, but they also pushed the discourse forward and affirmed that, in fact, institutions can and do exist on the African continent and are important for people in the world to learn from. It’s not just putting Africa in the receiving position or in the object position where one has people in the diaspora or working out of New York, London, Paris. It’s just as important to think from Dakar as it is to think of Dakar; it’s just as important to think from Lagos as it is to think about Lagos. They set such strong foundations. But of course, it’s precarious, right? It’s difficult because material conditions continue to inform what is possible. Not being romantic about it is healthy and necessary.

Embser: When you were working with Marilyn Nance on her book Last Day in Lagos (2022)—about an American photographer looking back at her exhilarating chronicle of FESTAC ’77 in Nigeria—was it important that the book was copublished by Fourthwall Books, a South African publisher?

Onabanjo: One thousand percent. We had to make sure that we were working with a publishing house on the continent. That was the most important thing. When I talk about precarity and longevity, being strategic and committed to the long view, it’s the fact that Last Day in Lagos was one of the last publications produced by Fourthwall Books, the fantastic publishing house in Johannesburg run by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen and Terry Kurgan. It was also one of the first books that the Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA), in New York, brought into existence. An international collaboration, I think, made the most fundamental sense, and it worked in terms of what the book needed. But if not for Fourthwall Books, I don’t think that book would’ve happened.

© the artist and Estate of Jean Depara

© the artist

Embser: Okwui Enwezor has said that the goal of In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present, his landmark 1996 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum exhibition, was very basic, to introduce a conception of African photography from the point of view of the auteur. Thirty years later, how would you describe your own goal for Ideas of Africa?

Onabanjo: Mine would be a slight transposition, as I remain a student of Okwui’s. My goal is to learn from an existing conception of African photography—which he shaped in tandem with Bisi Silva, N’Goné Fall, Simon Njami, Koyo Kouoh, and many others. Due to their collective work, the foundation has been set. Now it’s time to build, to take things to exciting different directions, and to recognize that the auteur is always working in collaboration.

Embser: And maybe books are one part of that.

Onabanjo: They’re a huge starting point. I think it’s the beginning and the open end. Because it’s not going to finish. We’re not done yet.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue,” in The PhotoBook Review.