Bisi Silva Changed the Way We See African Photography

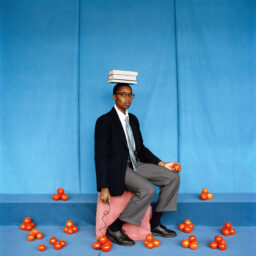

Bisi Silva, New York, 2016

Photograph by Gabriela Herman/The New York Times/Redux

When the time comes to reflect on the titans who shaped the course of photographic practice in Africa during the early twenty-first century, the name Bisi Silva, who died last week in Lagos, will be writ large, emphasized in bold. Over more than twenty-five years in the field of contemporary art and photography, her remarkable vision and indefatigable spirit instigated tectonic shifts in editorial, curatorial, and institutional frameworks in Nigeria and across the African continent. A curator trained at the Royal College of Art in London, and a contributor to publications including Artforum, Third Text, and Art Africa, Silva responded to the flows of the global, but was ultimately grounded in a granular treatment of the local, which she defined as “an expanded field of practice and engagement.” Situating her curatorial practice within Nigeria, Silva founded the nimble, impactful organization that is the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) Lagos in 2007, which provides a platform for the development, presentation, and discussion of visual art and culture. Her CCA Lagos exhibitions included Democrazy (2007–8), Lucy Azubuike and Zanele Muholi: Like a Virgin (2009), and Kelani Abass: If I Could Save Time (2016–17), among many others.

In 2011 Silva organized Moments of Beauty, the first comprehensive survey exhibition of Nigerian photographer J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (1930–2014), at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Kiasma, Helsinki, initiating a period of long-term engagement with Ojeikere’s dynamic body of work. During 2012–13, she initiated The Progress of Love, a transcontinental collaboration between Houston’s Menil Collection, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in Missouri, and CCA Lagos, which explored evolving modes and significations of love through work by artists from across Africa, Europe, and the United States. The year 2014 found Silva curating Playing with Chance, an in-depth solo exhibition on El Anatsui at CCA Lagos, which drew deeply on archival and photographic material from Anatsui’s studio. She also served as a member of the international jury for the 2013 Venice Biennale, the Pinchuk Art Centre’s 2014 Future Generation Art Prize, and the 2018 Hugo Boss Prize.

A tireless tour de force, Silva organized the Second Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art, Greece (2009), cocurated the seventh Dak’Art Biennale de l’Art Africain Contemporain, Senegal (2006), and served as the artistic director of the tenth Rencontres de Bamako, Biennale Africaine de la Photographie (2015). Entitled Telling Time, Silva positioned the biennale—in collaboration with associate curators Yves Chatap and Antawan I. Byrd—as a space to explore the multiple valences of temporality within a Malian context, featuring a dizzying number of experimental and exciting approaches from artists based across the African continent and throughout the African diaspora. Including a focus on Lusophone African photography, a core engagement with Malian studio photography archives, and ambitious visual literacy initiatives, she amplified the scope of what kinds of curatorial, programmatic, pedagogical, and artistic modes could be engaged through a photography biennale’s mandate.

Yet beyond these direct interventions and contributions, what Silva has done for the fields of contemporary art and photographic practice might be felt in the most embodied manner through the six cohorts of curators, photographers, and artists that she cultivated from 2010 to 2016 through the Àsìkò International Art Programme, a pioneering pedagogical model that employs a nomadic framework to stage intensive workshops for artists and curators across the African continent. Nurturing dialogues between emerging practitioners as well as invited international guest artists, scholars, curators, and cultural administrators, Àsìkò stimulates critical and conceptual thought, while also spurring meaningful dialogue, exchange, and collaboration. It also provides a vital space within the field of contemporary artistic practice where the perspectives of those working within the African continent are foregrounded first and foremost.

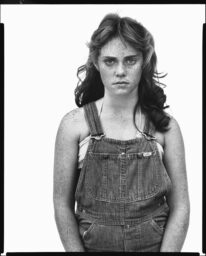

© the artist

Silva was also a record keeper—a librarian, an archivist, an editor. As an extension and constitutive element of her curating, she concentrated on the importance of accumulating and caring for visual histories through publications. At CCA Lagos she accrued what is now the largest photographic and visual arts library in Nigeria, a collection of photobooks, artist monographs, theoretical texts, exhibition catalogues, historical accounts, and journals numbering in the hundreds. Silva’s 2015 monographic publication on Ojeikere stands as a rich tome of photographic research, featuring more than two hundred images taken over more than sixty years, ranging from his typological survey of Nigerian hairstyles to his architectural studies of Lagos. The accompanying catalogue for Silva’s iteration of the Bamako Biennale featured not only original texts and beautifully executed spreads for each of the artists in the festival, but also a detailed timeline and complete reprint of the catalogue for the biennale’s inaugural 1994 edition. With an editorial team of twenty contributors, Silva offered a cogent point of entry for considering the historical framework of the biennale and contemporary photographic practice within Africa.

In 2017 Silva published Àsìkò: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa, a volume that documented the six iterations of the program and indexed the reflections of the seventy cultural producers that participated in the program. Edited and designed in collaboration with Stephanie Baptist, Nontsikelelo Mutiti, and Julia Novitch, the book emulated the multivalent nature of the program by incorporating archival materials and documentation from each edition alongside a number of critical and theoretical essays, interviews, and artistic works. The same year, Silva was also a guest editor for Aperture’s “Platform Africa” issue, where, alongside coeditors John Fleetwood and Aïcha Diallo, she tracked the various sites and spaces across the continent that inform contemporary photography in Africa. A true luminary, she enriched and sustained the field of contemporary art and photography tenfold.

In the process of writing this piece, I returned to old notebooks, catalogues and exhibition leaflets, saved bookmarks, program ephemera, and extended email threads—all in an attempt to pinpoint precisely when Bisi Silva entered my life. As often is the Nigerian way, we were connected through family. She was generous from the start, and through her guidance, I learned the importance of retaining an astute eye, an ambitious scope, a sensitivity to tracking artistic growth, and a set of standards predicated on asking the hard questions—of myself, my collaborators, and the photographic medium itself. It is a point of pride to note that this experience of being mentored by Silva is not particularly unique to me. She has equipped countless individuals with the tools to make room in this field for thoughtful, critical consideration of photographic practice on the African continent. Across varied contexts, time zones, and geographic spaces, Silva pursued her work with rigor and care, with an exuberance for the present and a deep respect for history. Writing in Telling Time in 2015, Silva quoted the griot Kouyaté: “I teach kings the history of their ancestors so that the lives of the ancients might serve them as an example, for the world is old, but the future springs from the past.”