In Okwui Enwezor’s Final Exhibition, an Urgent Portrait of American Life

The late curator’s visionary project about Black grief and white grievance arrives at an inflection point in US history.

Garrett Bradley, Still from Alone, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Okwui Enwezor imagined the exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America as a direct and necessary intervention into the 2020 presidential election campaign in the United States. If the show had opened as planned, at the New Museum in New York last October, it would have been poised to interrupt—albeit from the margins of high culture—the chaotic, overheated, and largely empty rhetoric of the political campaign with an elegant articulation of substantive artistic responses to the harrowing and unrelenting experience of extreme anti-Black violence in this country, coalescing rather beautifully with months and years of critical thinking and crucial protest from the Black Lives Matter movement. But Enwezor died in 2019 at the age of just fifty-five, following a long fight with cancer. Nothing went as planned last year, and so the show was postponed.

Now, after the inauguration of Joe Biden, the staggering loss of more than half a million people in the US alone due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the truly shambolic end to Donald Trump’s one-term presidency, and yet more unconscionable racist violence, Grief and Grievance has finally opened under different circumstances—thanks to the artist Glenn Ligon and the curators Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, and Mark Nash, who served together as advisors. The delay has added to the exhibition’s strength. Creating a semblance of distance while making plain all the things that remain unchanged, the lag time has only deepened the many dimensions of meaning and illuminated the layers of complexity that have been carefully worked into the show. This is especially evident in the role film and photography play, with a series of exceptionally strong image-based artworks plotting their own delicate path through Grief and Grievance—drawing on, while at the same time dismantling, virtually all of the usual narratives, traditions, categories, and disciplinary boundaries of these art forms.

Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

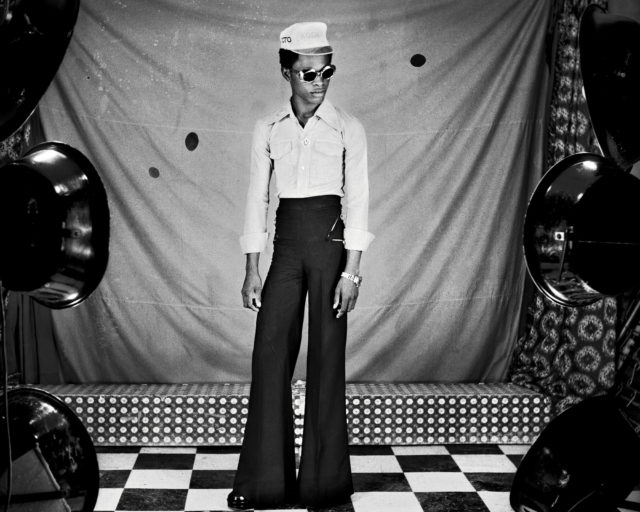

Enwezor, a big thinker known for his maximalist approach to space, was born and raised in Nigeria. He came to the US as a young man—fiercely intelligent, sartorially sharp, unapologetically cosmopolitan—and studied political science. Then he made a place for himself in New York City’s downtown poetry scene. Much of his eventual curatorial work was notably focused on photography. Landmark shows (such as In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present in 1996; Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography in 2006; and Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life in 2012) delved into the vast milieus of African image-makers, many of whom were legendary in their wider worlds but largely unknown in the US and Europe. These artists’ works were tangled up in literature, music, and the legacies of colonialism and national liberation politics. Knotted historical threads—in addition to the studios, clubs, magazines, and collectives that had brought these artists and the contexts of their work to attention—were always present in Enwezor’s exhibitions. As Gioni, the New Museum’s artistic director, has noted in the various talks and texts around Grief and Grievance, the only institutional position Enwezor ever actually held in New York, a city he called home, was as adjunct curator at the International Center of Photography.

For a show of thirty-seven artists, Grief and Grievance is remarkably well-rounded in terms of style, material, and media. Some of the exhibition’s moments of force and clarity come through paintings and sculptures that create the formal language to convey palpable trauma and irrepressible joy; and through works such as Tyshawn Sorey’s Pillars (2018), Theaster Gates’s Gone Are the Days of Shelter and Martyr (2014), and Okwui Okpokwasili’s Poor People’s TV Room (Solo) (2017), which mesmerize primarily through sounds that drift through the different rooms, pulling you in for a time and then haunting you as you move away from them. But if you find your way through the exhibition as I did—starting in the lobby gallery, with the incredible precis created by screening Garrett Bradley’s stunning short film Alone (2017), in the same room with Terry Adkins’s majestic large-scale X-ray images of memory jugs and Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s horrifying sculpture of a cattle squeeze; then climbing up through the second and third floor galleries, through rooms devoted to works by Carrie Mae Weems, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Deana Lawson, and Dawoud Bey; and coming back down to end in the coda of Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016)—then clearly, a thesis emerges on the uses of photography in relation to race in America.

© the artist and courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, and Rennie Collection, Vancouver

Beckwith’s revelatory essay in the catalogue, “My Soul Looks Back in Wonder,” fleshes out this thesis, exploring how early photography served to objectify Black bodies and commodify their suffering. Pseudoscientific images were used as supposed evidence to create racial categories and sustain the myth of white supremacy. Postcards with lynching pictures were traded as awful souvenirs. With the story of Emmett Till, and the pictures of his open casket and his mother’s grief, images of Black mourning began to shift the position of documentary photography and photojournalism, “refashioned,” writes Beckwith, “as potential tools in justice work.” Photographs of the Civil Rights movement began the process of restoring dignity, complexity, and the fullness of Black experience, aspiration, and deep historical knowledge. What stubbornly persisted, however, was the interminability of Black suffering and the continued ubiquity of its imagery, ever present to this day. “Living with trauma and acute grief,” Beckwith concludes, “is our black life, our dexterity, our inheritance.”

Grief and Grievance presents tremendous examples of the works artists have made from that inheritance. Bradley’s video, about her friend Aloné—a single mother in New Orleans and a subject of fulsome Renaissance-level beauty, who is measuring the decision to marry her beloved and to foreclose her bright future by becoming the bride of an imprisoned man—ties the legacy of slavery directly to today’s carceral state. The work carries the force and truth of documentary with the composure and poise of fiction. And the glimpse we get of Aloné’s maybe future husband, a man passing by the camera at a distance (his smile a flash and then gone), electrifies, no matter how much we may think we know better.

Courtesy the artist; JTT, New York; and Carlos/Ishikawa, London

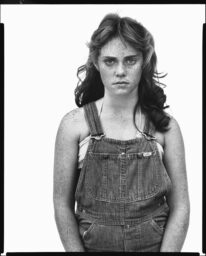

Sable Elyse Smith’s elusive series of family portraits—the images are taken in prisons against brightly painted murals, the pictures nearly swallowed up by huge frames of black suede—offer a thread. Tug on it and an entire economy of incarceration unravels, including the racist policies that have kept it going. An excerpt from LaToya Ruby Frazier’s monumental series The Notion of Family (2001–14) conveys the material, emotional, and psychological destruction of an archetypal postindustrial town more bracingly than any economist or sociologist could. The extreme intimacy and tender gestures that Frazier captures in her photographs, packed as they are with details and contexts, stick in the mind for ages—especially here, with an unforgettable image like Mom Holding Mr. Art (2005) echoing the possible fate of Bradley’s Aloné. In paintings by Julie Mehretu and Jack Whitten, photographs of police brutality and white nationalist violence are almost totally sublimated and overwhelmed by the marks of their makers, yet they remain as traces. And on numerous occasions, the still and moving images present in Grief and Grievance allow the world to come rushing into an all-too-often inward-looking discourse, adding a globalized perspective and exposing many connections from the American experience to the repercussions of the Atlantic slave trade and the long, unsettled history of colonialism.

As Mehretu noted in a panel discussion a few days after the opening of Grief and Grievance, Enwezor planned for the exhibition to open in a liminal space, on a threshold. “It’s interesting that this show comes about during the time where the United States really failed for the world, and exposed itself as a colonial project, a continued colonial project,” she said. “Okwui took this opportunity, with the words and the language around the exhibition, to give it this intellectual framework,” to show “how the US is a participant in this larger, colonial, transnational reality, and how it’s in that state. It’s not in a postcolonial state whatsoever, as many places on the continent, in Africa, and in the Global South aspire to be.”

Photograph by Dario Lasagni. Courtesy the New Museum

As our inheritance, Enwezor left behind landmark exhibition histories, as well as robust catalogues, substantial writings, and resonant terms such as “the racial sublime” and “the colonial sublime,” alluded to in the work around Grief and Grievance. But mainly, he left us with a lot of work to do. Until this show, I had never seen Jafa’s Love Is the Message on a screen bigger than my phone. I was living outside of the US when it was first presented, shortly after the 2016 US presidential election, and I missed years of chances to see it in person. The projection at the New Museum is mural-size, the soundtrack all-consuming; Love Is the Message has rightly been called the Guernica of our time. An elastic approach to time binds the work together—Angela Davis striding in glorious slow motion, the pause before Barack Obama begins to sing “Amazing Grace,” the seemingly sped-up chaos of gratuitous police violence, a child crying out as a father figure schools him in how to survive as a Black boy in this country.

In Jafa’s film, as elsewhere in Grief and Grievance, it’s not so much catharsis or transcendence, but the maximum intensity we can bear: this weight and this light, this horror and this joy, this stunning achievement and this cruel, baseless punishment—all of it our doing. A young woman asks, momentously: “What would America be like if we loved Black people as much as we loved Black culture?” Maybe the real intervention of Grief and Grievance is to demand that we imagine a good answer to that question, and then make it so.

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America is on view at the New Museum, New York, through June 6, 2021.