Essays

What Christopher Gregory-Rivera Discovered in Puerto Rico’s State Secrets

For decades, US officials sought to suppress independence movements in Puerto Rico, spying on activists and their families. What do their formerly secret files reveal?

As a high school student in Puerto Rico, around 2005, Christopher Gregory-Rivera grew active in student movements that fought university tuition hikes. His mother wasn’t happy about it. “She would say, ‘Cuidado, te van a carpetear,’ which meant that the police were going to open a file on me,” Gregory-Rivera told me recently. “That was my first exposure to the idea that the police were opening files, or carpetas, on dissidents. I was like, ‘Mom’s crazy, she’s paranoid,’ but it turned out to be something that’s super present in Puerto Rican protest culture and the Puerto Rican imaginary in general.”

Gregory-Rivera’s mother’s warnings prompted questions about his homeland, and he soon learned the violent history of carpetas (“folders”). Since the early 1900s, an active independence movement sought to wrest Puerto Rican sovereignty from the United States, while the Puerto Rican government and high-ranking US officials such as J. Edgar Hoover sought to suppress activists through tactics that ranged from monitoring to murder. By 1978, pressures came to a head when an undercover police agent named Alejandro González Malavé led the independence activist Arnaldo Darío Rosado and his teenage associate Carlos Soto Arriví to Cerro Maravilla, a mountain at the center of the island. The young men allegedly planned to set fire to or bomb television towers positioned there but were met by officers who killed them in a barrage of gunfire.

The island’s governor at the time, Carlos Antonio Romero Barceló, later called the police officers “heroes,” in accord with the official story—that the victims had been terrorists and the police acted in self-defense. But in 1983, the Judiciary Committee of the Senate of Puerto Rico determined the youths had been executed by the police to intimidate the independentistas. (It also turned out that the FBI had advance knowledge of the ambush.) During the prosecutions that followed, a former agent of the Intelligence Division, William Colón Berríos, admitted the police kept files on activists. The whispered fears of being “foldered” had circulated through Puerto Rico for decades but, until that time, were often chalked up to rumor. Now people learned the stories were real. Since the 1930s, the police had investigated at least 135,000 individuals (about 3 percent of the island) suspected of favoring independence. Moreover, they’d used informants—suspects’ associates, friends, and sometimes even family members.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

These revelations gave way to litigation, and in 1988 the Puerto Rican Supreme Court declared that the police’s dossier practice violated the constitutional rights to speech, association, and privacy, while also insulting “the dignity of the human being.” The court required that the files be returned to their subjects, a measure the legal scholar Marc-Tizoc González describes as “habeas data.” Instead of instituting a formal protocol that would help give citizens some emotional closure, people were simply told to come to the Center to Arrange Confidential Records and pick up their unredacted papers. There was no reconciliation process, no truth commission. Beginning in September 1989, people grabbed their files from the Center, took them home, read them, and then stored them in their bureaus or cupboards. If no one showed up to claim a carpeta, it was stored in the National Archives, where many remain today.

Twenty-four years after this process began, Gregory-Rivera was in Washington, DC, striving toward his dream of becoming a photojournalist. Posted to the White House and on Capitol Hill while working as an intern for the New York Times, he began to reimagine his career when he heard about Edward Snowden’s 2013 data leaks, which revealed that the National Security Agency had collected the phone records of millions of Verizon customers. “Everyone was like, ‘It’s not important, I have nothing to hide,’” Gregory-Rivera says. “But I knew that in Puerto Rico, everyone is afraid to express themselves politically because they think that the government is watching them. I had this crisis. So, I went back to Puerto Rico and started this project.”

The project turned into a two-phase undertaking. In its first stage, Gregory-Rivera approached people in possession of their carpetas and asked to photograph the documents. “I did it guerrilla- style, setting up little studios in people’s homes. I found the images detonated a sense of reality to a chapter of our history that a lot of people are not familiar with, especially the younger generations,” he explains. The effort resulted in the series Las Carpetas (2014–ongoing), which shows the files as Gregory-Rivera encountered them: “A lot of people were like, ‘What the hell is he doing?’ when I’d bring all this equipment into their houses. But some are really proud of how big their carpeta is, it’s as if that was a sign of their commitment to the movement.”

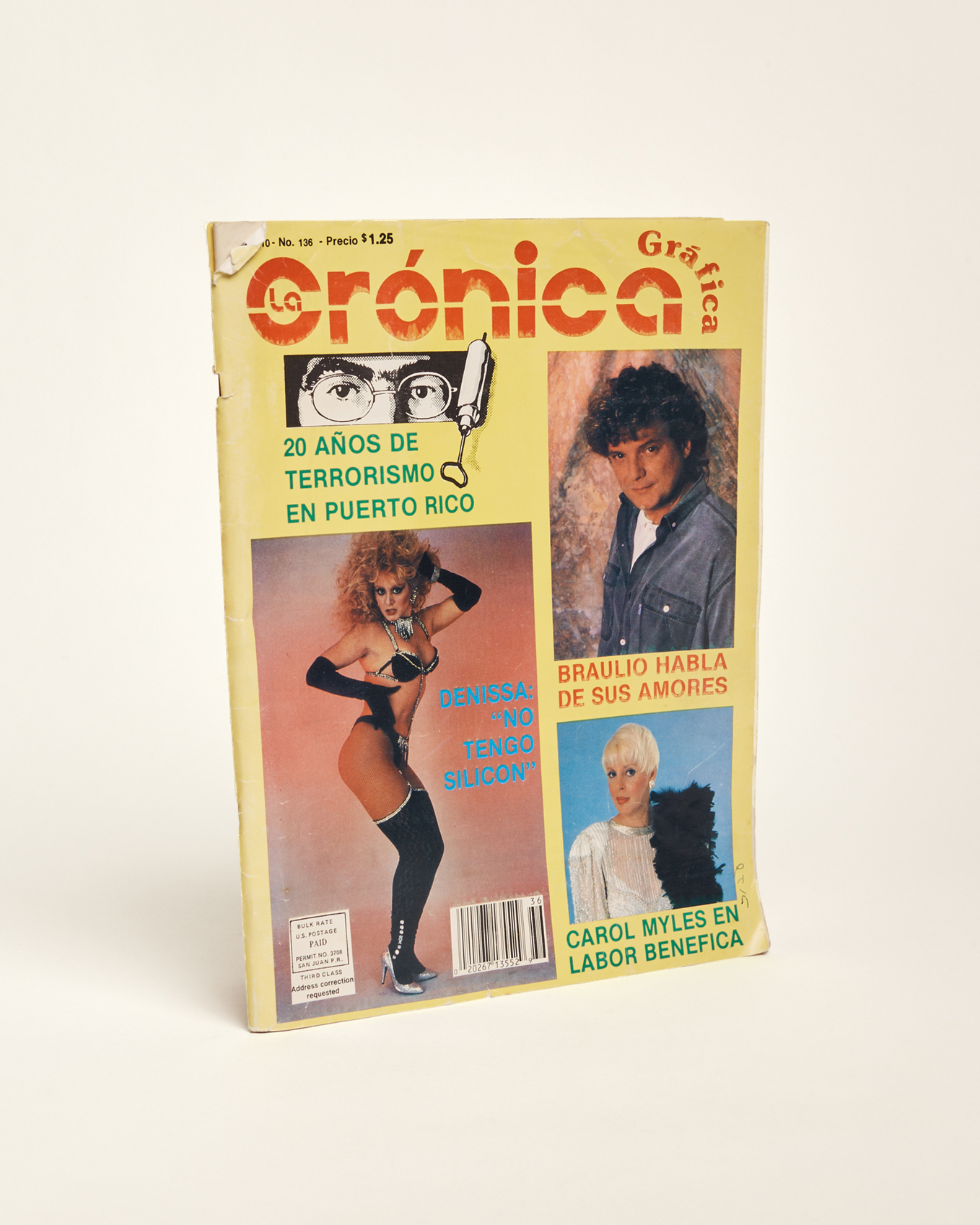

A striking picture in Las Carpetas showcases a massive stack of manila files overflowing with mug shots and chillingly banal reports on the comings and goings of dissidents: one account describes a subject “seen cruising around in a green 1952 Studebaker, license plate 625-420.” Others amount to loving portraits of the books confiscated from presumed independentistas—Kim Il Sung’s biography, William J. Pomeroy’s Guerrilla Warfare and Marxism. “The intelligence department had one of the most extensive archives of leftist literature,” Gregory-Rivera tells me, wryly.

The surveillance photographs show an artist’s flair, revealing the care with which spies conducted their craft.

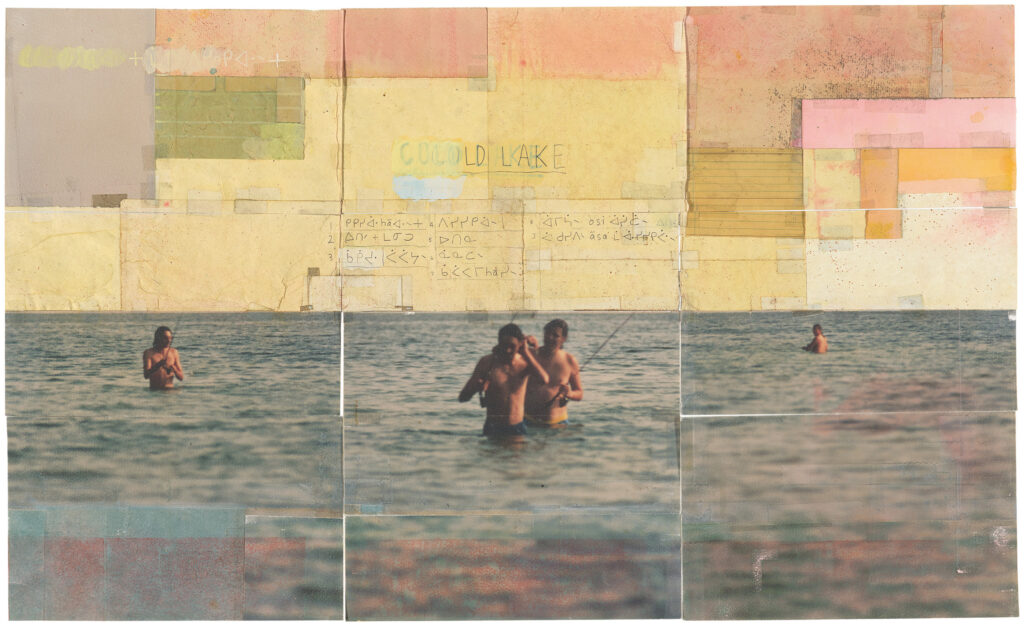

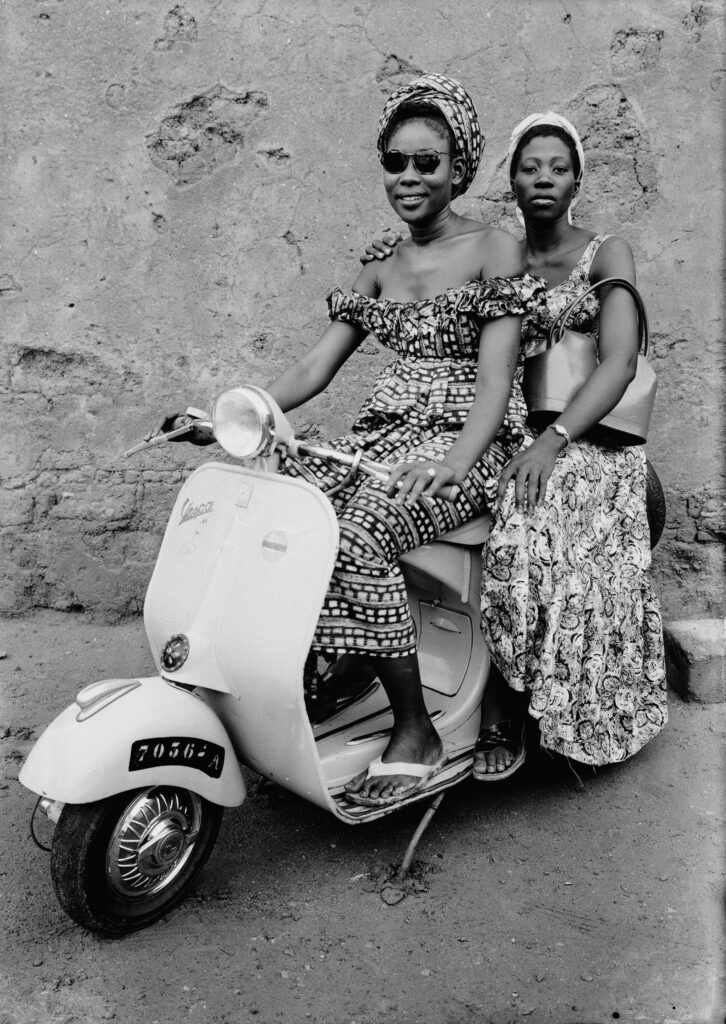

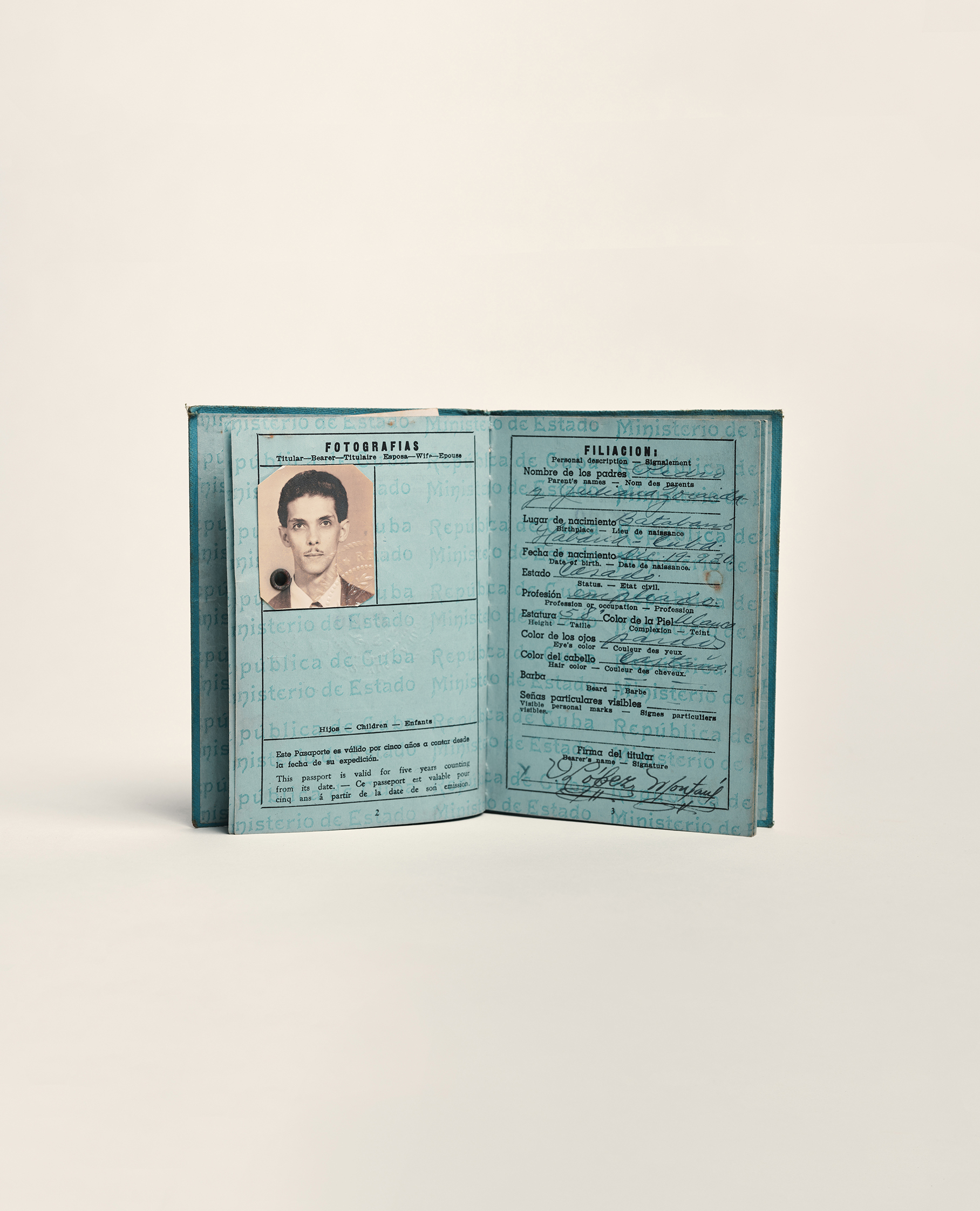

Gregory-Rivera’s project gained depth and intensity when, in 2014, he began digitizing the files orphaned in the archives, including the surveillance photographs. Many of the pictures in the carpetas look like they could come from a family scrapbook or were ripped from refrigerator magnets, but they are actually surveillance images taken by government agents. An image, appearing to be from the 1980s, discloses two men sporting matching mustaches standing close together in fetching white shirts. Another photograph (possibly circa 1970, judging from one man’s slim, striped pants) shows a woman lying on the ground, screaming with laughter, as friends try to help her up. Elsewhere, a woman in a white suit is caught in an obsessive, Eadweard Muybridge–like sequence as she opens the door of a car, takes off her blazer, and prepares to enter the vehicle. Additional evidence of the surveillance’s persistence and duration surfaces in an annotated image that likely dates from the 1940s or 1950s, its five male subjects wearing natty sport coats and full-legged trousers reminiscent of midcentury zoot suits.

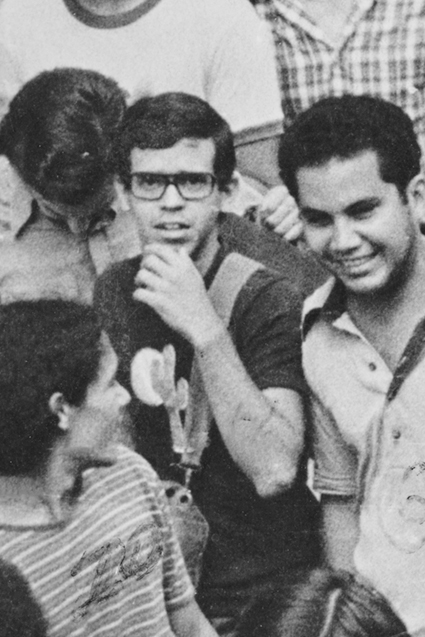

The surveillance photographs show an artist’s flair, revealing the care with which spies conducted their craft: a smiling man, eating from a plate, leans against a telephone pole, creating a focal center of gravity with his pals arrayed behind him, grinning and hoisting signs. In a scene that tells a recognizable story of obligation and boredom, five people occupy a waiting room, watched over by what appears to be a Coppertone ad bearing the disorienting slogan “Don’t Be a Paleface!” The women are carefully adorned in stockings, scarves, and curled hair, while one man smiles for the camera, his lap burdened with his and his wife’s bulky coats. But the details of this event are lost to us—we don’t know where the subjects are, what they are waiting for, or what happened to them when they left this space.

Gregory-Rivera collected these photographs and a cache of about sixty more, compiling them into the mesmerizing book El Gobierno Te Odia (The government hates you, 2023). Made on a Risograph machine, which replicates the texture of an old-fashioned Xerox copier, the tome is hand-bound with screw posts that mimic the accoutrements of what the photographer calls “office culture.” For the larger part of the book, Gregory-Rivera presents the photographs with minimal identifying information in order to replicate the mystery and confusion he encountered in the National Archives. Toward the end of El Gobierno Te Odia, however, he appends narratives to a small selection of images.

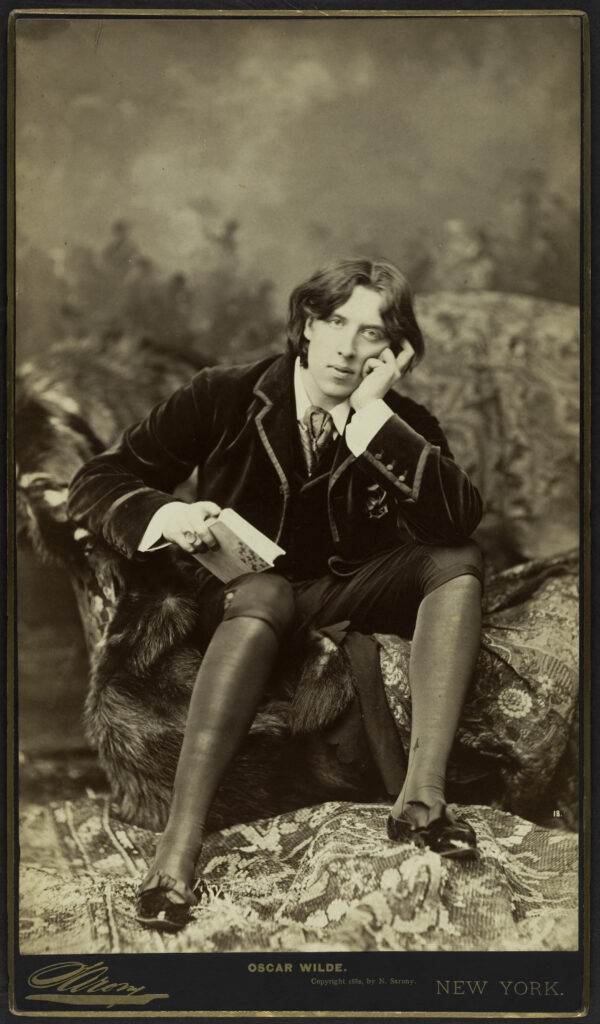

One such picture shows a feminist activist wearing a striped hat and carrying a sign that bears the words “La violación es un acto de agresión” (“Rape is an act of aggression”). Below the image, Gregory-Rivera’s text reads: “By the late 1970s and early ’80s leaders of both leading parties realized they could use the Intelligence Division to control ideology beyond independence. Feminist, labor, and environmental organizations were also targeted by the secret police.” We also see a photograph of a smiling woman posing before two cakes that are lavishly frosted with the letters “FUPI” (for Federación Universitaria Pro-Independencia) and “PSP” (for Partido Socialista Puertorriqueño) and planted with US flags bearing fifty-one stars, evincing the subject’s ambition for Puerto Rico to become a state: “A presumed agent or employee of the Intelligence Division poses with a cake . . . decorated with frosting spelling acronyms of the various organizations the Division surveilled,” Gregory-Rivera’s text explains. Perhaps the most painful photographs in El Gobierno Te Odia are found in a diptych of Arnaldo Darío Rosado, who died at Cerro Maravilla. A 1975 portrait of the intense, bespectacled young man shows him looking at the camera while standing in a crowd of comrades; its companion image displays his bloody body lying in a field.

Gregory-Rivera’s work with archives exposes surveillance’s long-standing wound. Organizations and societies have betrayed their citizens in similar ways—the FBI notoriously monitored civil rights activists in the 1960s and ’70s—but some have attempted to facilitate restorative justice: For former citizens of East Germany, officials made Stasi files available to the public and, in the 1990s, also convened two truth commissions that held public hearings. In 2022, Colombia’s Truth Commission issued a report on that country’s conflict, addressing illegal spying and lambasting US policy. Yet—as is the case with other US surveillance schemes, such as that of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission—there has been no collective process to address the injustice of las carpetas.

When I asked him whether he was trying to build a space for mourning and resolution, Gregory-Rivera affirmed that the silence surrounding las carpetas motivated him. “What I’m doing goes hand in hand with creating dialogue, however painful or complicated or controversial,” he says. “I think these events need to be rescued because of the current political situation in Puerto Rico. This history helps us understand where we come from and to modulate for self-determination on a basic level. It can help us move into the future, and part of that process requires reconciling this history and bringing truth to the foreground on a larger scale.” Las Carpetas and El Gobierno Te Odia allow the victims of surveillance, their descendants, and the United States as a whole to bear witness to a sordid chapter of history. Gregory-Rivera’s work offers the opportunity for us to consider the record of political persecution and to imagine new ways of healing and moving forward.

Photographs by Christopher Gregory-Rivera © the artist. Archival images courtesy the Archivo General de Puerto Rico, San Juan

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories,” produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation.