Portfolios

When Luigi Ghirri Photographed the Ferrari Factory

In the mid-1980s, Ghirri was invited to make promotional photographs for the mythic carmaker. His images bring the company down to earth from the upper stratosphere of luxury.

Luigi Ghirri did not preoccupy himself with cars, but he did enjoy driving. He owned a number of Volkswagen Beetles that were constantly breaking down. In the 1980s, he switched to a Volvo station wagon, paragon of Swedish vehicular functionality and safety. An accumulation of unpaid traffic fines suggests he may not have been a great driver, or that he was blasé about traffic rules. Nonetheless, he crisscrossed Italy and Europe taking the photographs for which he is now celebrated: unpeopled landscapes that rush toward a vanishing point, architectural details, found images within images pasted around a town. All are realized in soft washes of warm color that cushion reality, making it feel ever so distant and dreamlike. Adele Ghirri, his daughter, who now manages his estate and archive from his former home and studio in Reggio Emilia, recalls that her father’s cars were unwashed, neglected. His focus, one can assume, was on looking out the window for pictures. As Ghirri wrote, he sought to “observe the outside world in order to represent it.”

For anyone growing up in and around Reggio, the mythic car manufacturer Ferrari, based in nearby Maranello, loomed large. The company, in a crowded field of contenders, is an apex of Italian style, industrial design, and brilliant ingenuity. Michael Mann’s recent film Ferrari dramatizes the origins of the firm and the personal travails of its founder, Enzo Ferrari. Even so, on-screen, the cherry-red cars throbbing along twisting roads emerge as the indefatigable protagonists.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

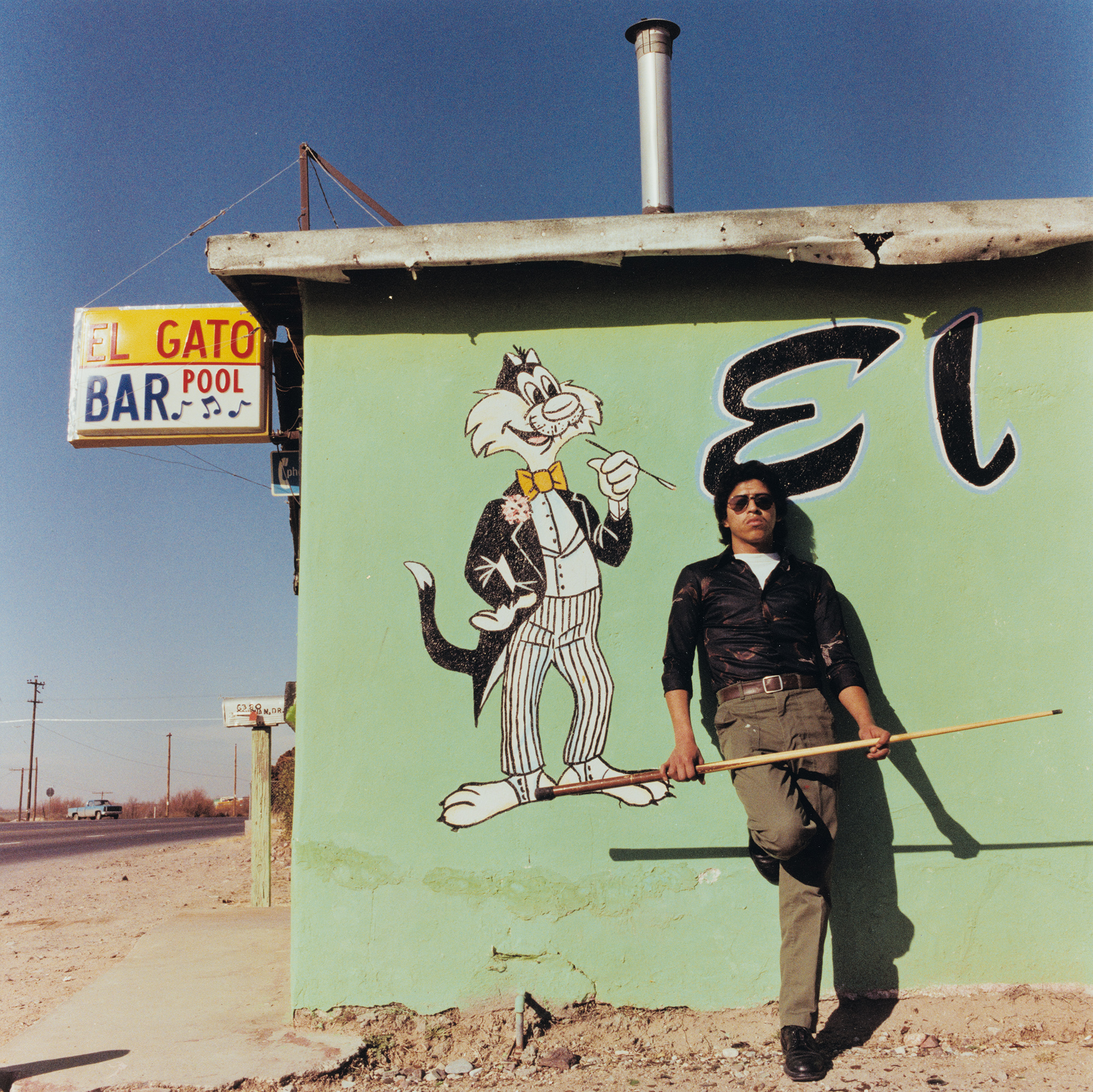

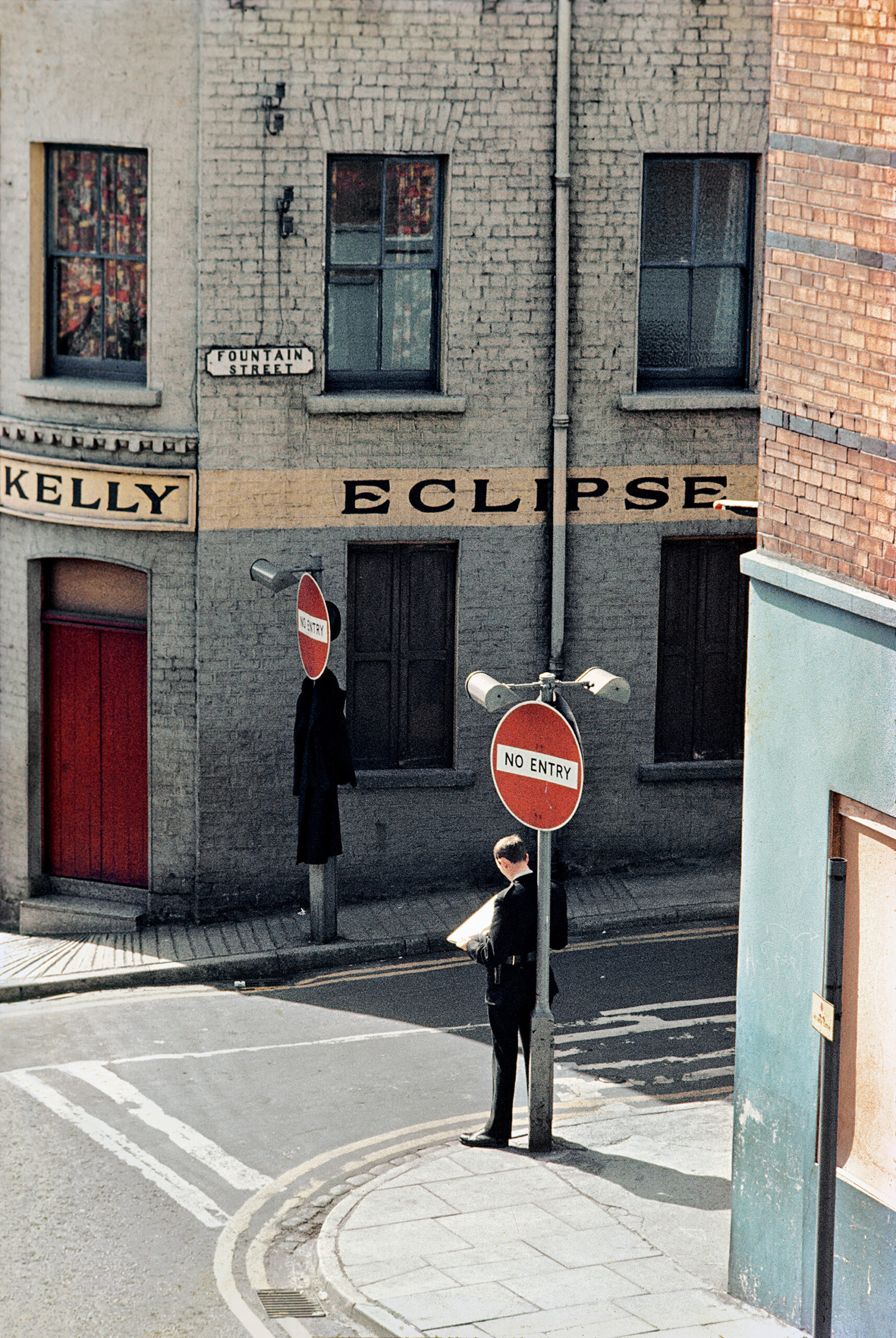

In the mid-1980s, Ghirri was invited to photograph at the Ferrari factory. The pictures feel like a laboratory record. Workers don elegant lab coats emblazoned with the company logo—that rearing horse. Interior leather samples are arranged in Ellsworth Kelly–like compositions. There is little sense of mechanical noise or grease. Even an image of molten steel being poured is quiet. By contrast, Chris Killip’s noirish pictures from the Pirelli tire factory, stylish as they are, and made around the same time, hint at noisier manufacturing underway. Ghirri’s Ferrari images haven’t been widely published or exhibited. Not made for the public, they were used in a promotional publication, designed by the influential architect Pierluigi Cerri, that also included photographs by Walter Iscra, Gianni Rogliatti, Wolfgang Wilhelm, and a selection from the Ferrari archives.

Ghirri’s interest in clean lines, perspective, and landscape can be traced back to his earlier job as a land surveyor. He was passionate about architecture and design, reading—and sometimes collaborating with—magazines such as Ottagono, Lotus, and Domus. He photographed many buildings by Aldo Rossi, an architect Ghirri admired for how the colors of his exteriors resonated with their surroundings. Like most photographers scratching out a living, Ghirri worked on commission from time to time, often merging image making with a story about design. In the 1980s the jewelry brand Bulgari hired him to take photographs of its newly minted Fifth Avenue store in New York. From 1975 to 1985, he worked with Marazzi, an Italian heritage tile company, using the opportunity of a commercial commission to create exquisite images of trompe l’oeil play and clever meditations on the act of picture making itself. The simple colored tiles presented a stage on which to work and arrange miniatures of a camera on a tripod, a baby grand piano, or, in a nod to Fra Angelico, an egg resting in a stand. A recently published book of Ghirri’s work, Italia in Miniatura (2024), explores his interest in the detailed facsimiles of famous sites and landscapes at a theme park in Rimini. Ghirri’s writings—his essays are prolific—ruminate on representations that shrink reality: postcards, atlases, Lilliputian worlds.

In the Ferrari images, too, there is a sense of making things small. As with his famous picture taken through a window at Versailles, deflating the ostentatious grandeur of the palace gardens, Ghirri’s photographs for Ferrari bring the company down to earth from the upper stratosphere of luxury. This is seen on the factory floor and in a 1990 photoshoot staged on a hilltop overlooking Florence. A group of cars selected to celebrate the company’s history was displayed and framed in an installation of cubes designed by Cerri. The Duomo is visible in the background. The cars look like toys. Describing the experience of being inside a Rossi building, Ghirri wrote: “There is also a joyous sense of wandering, magically, inside a wonderful toy, getting lost and finding one’s way amid the gears and little wheels.” The same might be said of his pictures for Ferrari. The pleasure of design is fully on display, and the glitz of a storied brand takes a backseat to a careful study of its component parts.

© Estate of Luigi Ghirri

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”