Interviews

How Susan Meiselas Documented Nicaragua’s Revolution

The photographer reflects on her experience working in Latin America and why it’s essential to revisit a body of work over time.

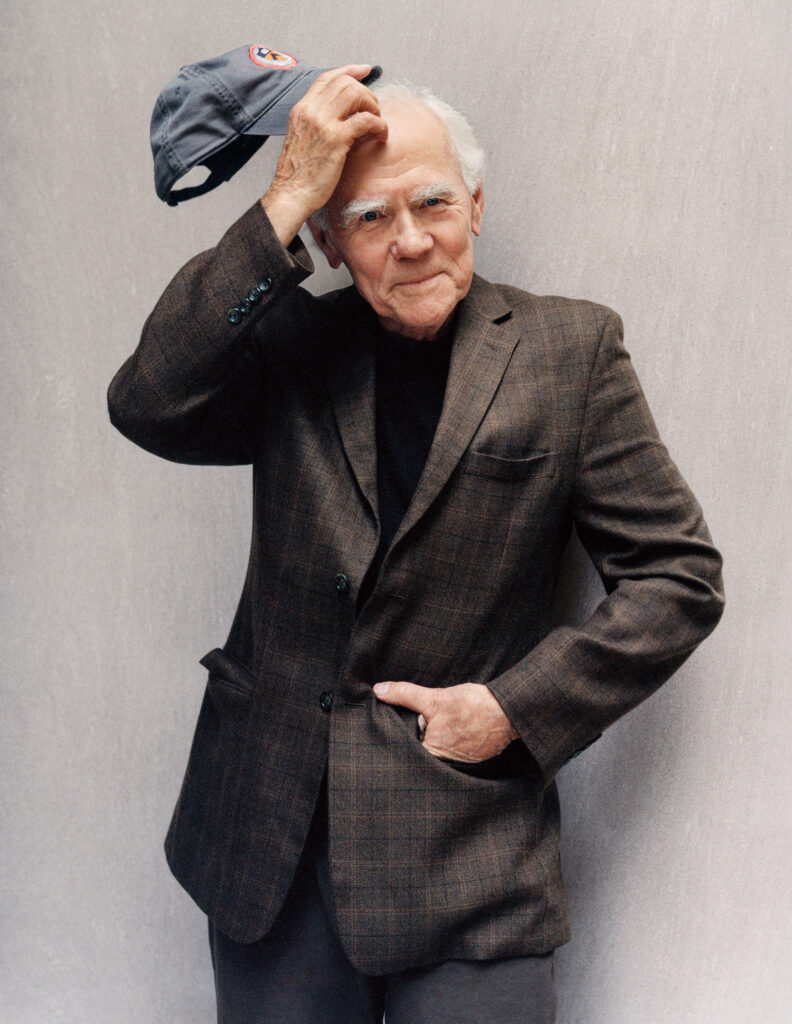

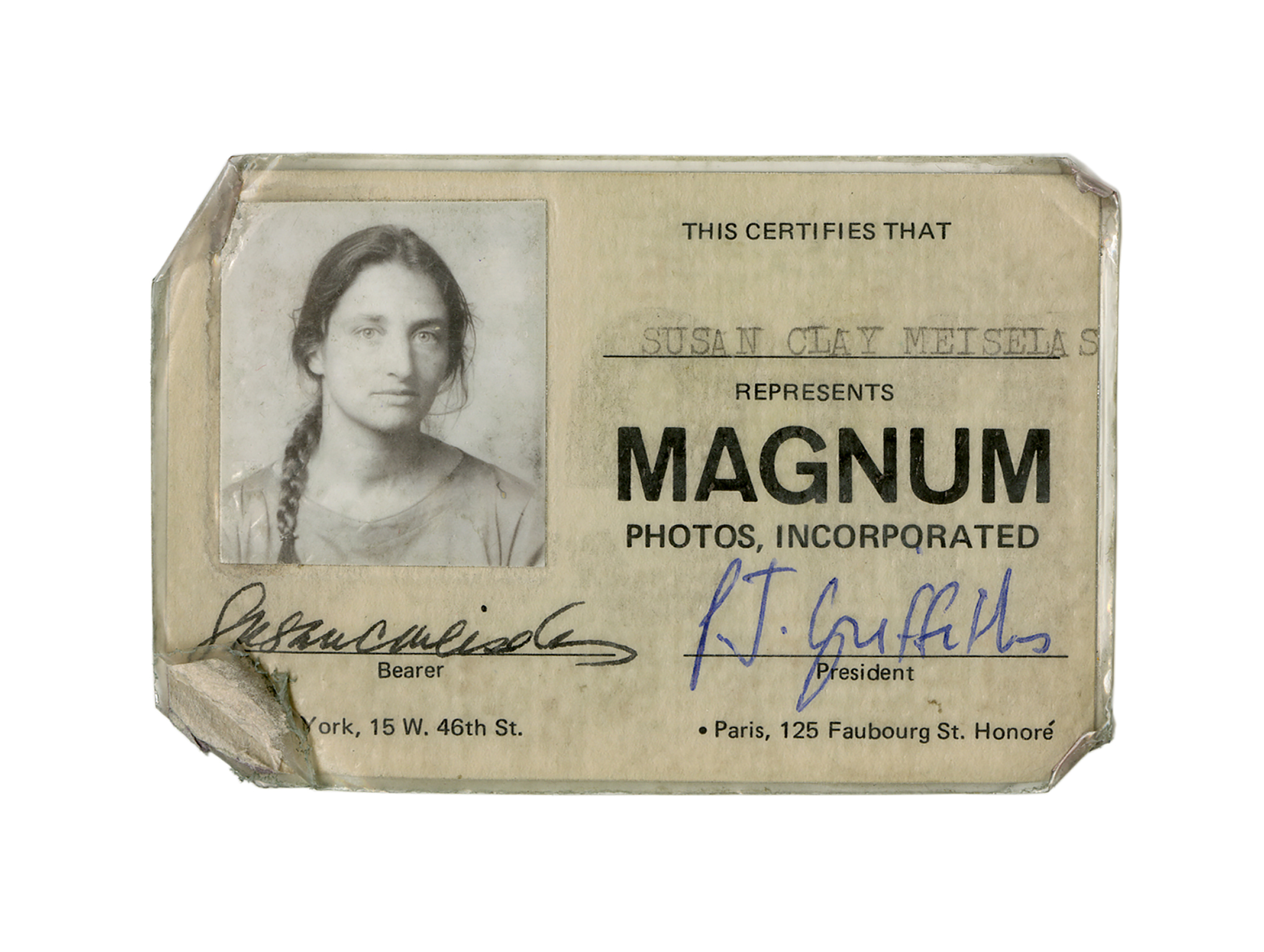

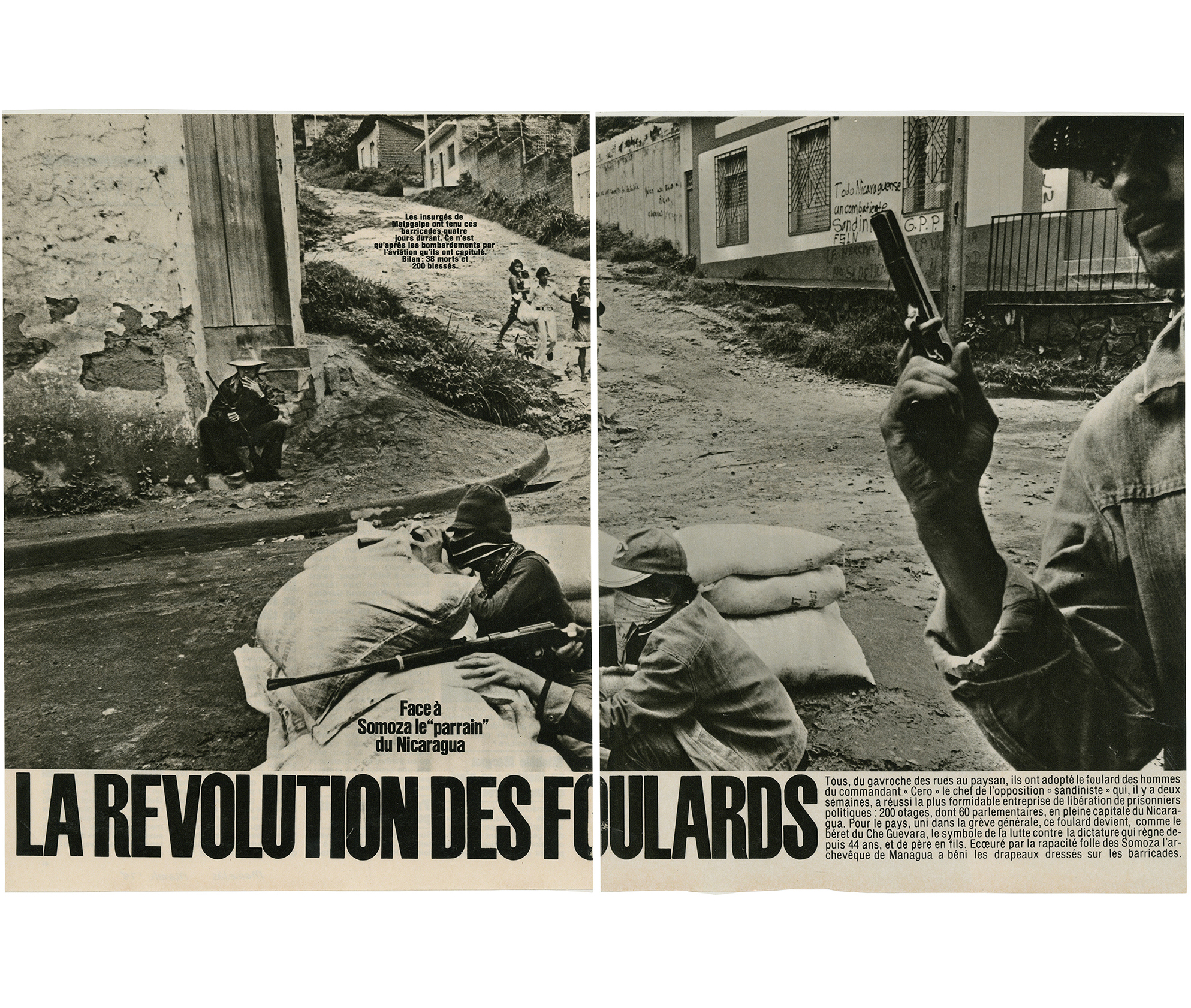

Susan Meiselas first traveled to Nicaragua in June 1978. Three years prior, Meiselas had joined Magnum Photos, and this trip marked her first experience working in conflict photography. Meiselas went on to spend just over a year in Nicaragua, documenting an extraordinary narrative of a nation in turmoil, from the powerful evocation of Somoza regime during its decline in the late 1970s, to the evolution of the popular resistance that led to the triumph of the Sandinista revolution in 1979.

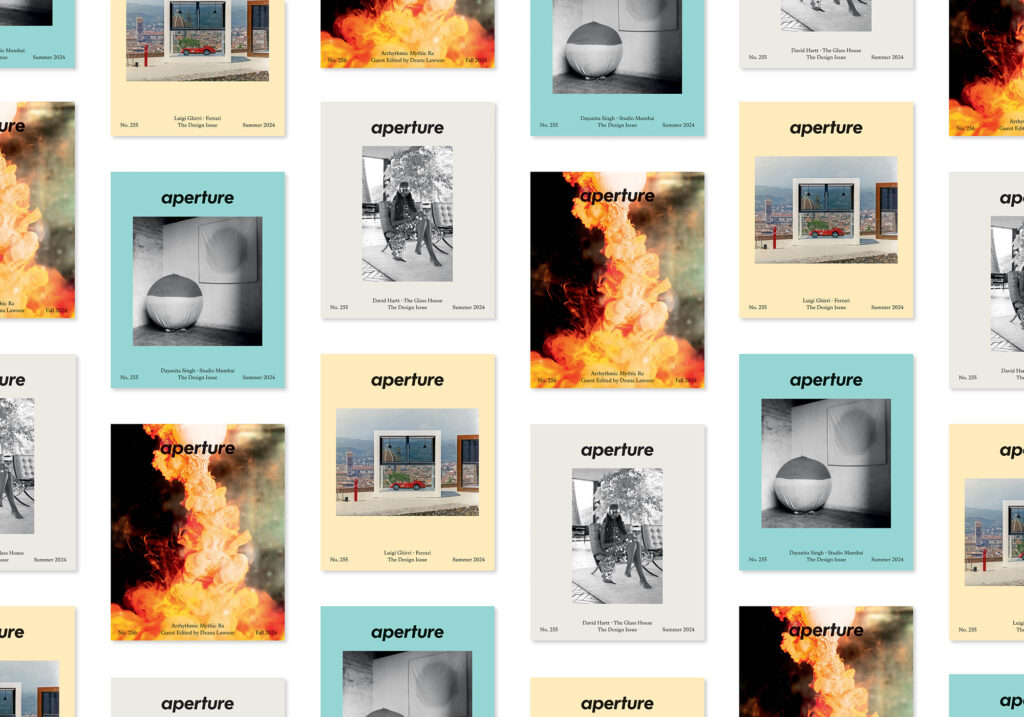

Originally published in 1981, and now in a third edition, Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 is a contemporary classic and formative contribution to the literature of concerned photography. In the decades following the original publication, Meiselas has continued to contextualize her photographs and relate them to history as it unfolded. In this new edition, thirty images are linked via QR codes to excerpts from films by the artist, including Pictures from a Revolution (1991, codirected with Richard P. Rogers and Alfred Guzzetti) in which Meiselas tracks down and interviews the people she photographed, and Reframing History (2004, codirected with Alfred Guzzetti), which highlights her collaborations with local communities installing mural-sized images in the places where they were originally taken, eliciting the memories and reflections of those passing by.

By extending and deepening her work, Meiselas asks us “to consider not only the specific timeframe of this book, but to think about the broader perspective of history unfolding, and how in the passage of time a photograph of a single moment in a person’s life shifts its meanings as well as our perception of it.” In an interview from the book, Meiselas speaks with Magnum Foundation’s director, Kristen Lubben, on how the work of this evolving project has been circulated, revisited, and repatriated—and how and why it endures.

Kristen Lubben: Before going to Nicaragua in 1978 you had never photographed conflict nor had you worked for the media. You were coming from what seems like a totally different universe than that of a war photographer: You were working on Prince Street Girls, portraits of adolescent girls in your Little Italy neighborhood, and two years earlier you had published Carnival Strippers, an extended photo-essay on women in traveling strip shows in New England, now a photo classic.

Susan Meiselas: Yes, Nicaragua was a quantum leap for me. Not only was the subject matter of Carnival Strippers and Prince Street Girls different than what I would encounter in Nicaragua, but I was also used to working in a different way—having extended relationships with subjects, and bringing back contact sheets for them to respond to. Carnival Strippers was the work I submitted to join Magnum, the photographer’s collective.

Magnum Photos press ID, 1978

Lubben: And did joining Magnum lead you to go to Nicaragua?

Meiselas: At Magnum there was a culture that supported taking initiative—going to a place not knowing more than whatever you could scrape together from afar. Remember, we are in a transformed world of information now; you can sit at home and do research online and feel you know a place without ever going there. But I had no idea what Nicaragua even looked like. I was reading snippets, these little stories that were ten lines long, and I wasn’t seeing any photographs with them. That made me think, “Maybe I should go—but how do you do that?”

The tipping point was a full-page New York Times article in January of 1978 about the assassination of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, the editor of the newspaper La Prensa and the country’s most outspoken opposition figure. Maybe it was the size of that article; maybe it was the way in which it implicated America in supporting the Somoza family. It all just started to turn in my head.

Through Gilles Peress at Magnum I met Peter Pringle, a British journalist working for the London Times. He had just been to Nicaragua, writing about the history of the English on the Atlantic coast, but hadn’t touched on what was happening with the brewing revolution, and was curious to do that. So I said, “Great.” I just assumed that’s what you do: find a writer you want to work with, and you go and do it. Then between February and when I ultimately left in June, there were more stories about Nicaragua—strikes and student protests, small events that kept percolating through the news. Peter, meanwhile, got bogged down and kept delaying the trip. One day I was at Magnum and [photographer] Richard Kalvar said, “I thought you were going to Nicaragua.” And I said, “Well, Peter can’t go . . . ” He said, “What do you need him for? You’re going to take the pictures.” It was kind of like, “Wow. Okay. That’s another idea.” That nudge helped me make the leap.

And I went. With no concrete plan in place. I didn’t speak Spanish. I didn’t even know where I would stay. It sounds nuts, but it’s true.

Lubben: So how did you get started? Did you just walk around Managua, taking pictures?

Meiselas: Yes, walking around, really feeling like I didn’t know what I was doing. But the first day, I went to La Prensa and I met with Carlos Fernando Chamorro, the son of the man who had been killed, and Margarita Montealegre, who was a young photographer at the newspaper. I was lucky that they both spoke English.

Lubben: Were there any other foreign photographers there?

Meiselas: There was one other, a Colombian photographer who came for a protest march, around the time Los Doce (The Twelve) returned to Nicaragua. Los Doce was an alliance of middle-class businessmen, lawyers, and professionals who aligned themselves with the Sandinistas against Somoza. They were kind of a legal front. The Sandinistas were underground. During that first trip I met many people who were sympathetic to the Sandinistas, but I didn’t meet anybody inside the organization. Or, if I did, I didn’t know that they were.

Susan Meiselas: Nicaragua

50.00

$50.00Add to cart

Lubben: Did you have any frame of reference in your own history for what you were experiencing in those early days in Nicaragua?

Meiselas: The students went on strike at the university in Managua when I was there. I might have chosen that image in the book because of the association I made with marching on Washington against the Vietnam War in ’68 during my own student years. I’m also of that generation where some people joined SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) and the Weather Underground, though that was not what I did. But the language of opposition was very strong at that time, along with the feeling that change was possible in America.

I think that’s probably why I was so intrigued by the question of how the Nicaraguans were going to overthrow a dictatorship that had been in place for fifty years. There were various sectors throwing their weight together, building momentum. The businessmen who owned the factories were supporting the workers who were on strike. Of course, no one believed they were really going to unify to the point that they would overthrow Somoza. The confrontation wasn’t constant, it wasn’t every day. It wasn’t until the insurrection in August 1978 that I was really in the middle of a war, and that was something totally unfamiliar to me.

Lubben: Is that when you shifted to shooting primarily in color rather than black and white?

Meiselas: When I first went to Nicaragua, I was working with two cameras, one loaded with black-and-white film and one with color. I started out thinking that I’d use mostly black and white, and it progressively became almost all color. It didn’t happen in the first six weeks; I think it just slowly evolved. I didn’t really switch; I think I just put more weight on one foot at a certain point. As time went on, the black and white became more like a sketchbook, so I knew what I had when I processed the film in Nicaragua. It was my reference set. I shot that way later in El Salvador, too. But in El Salvador I made the opposite decision. Although there is color from El Salvador that I like quite a lot, at that time I really decided the work was stronger in black and white.

Lubben: You felt Nicaragua was better served by color film.

Meiselas: Yes. Well, not “better served,” because that sounds like I’m in service of it. It’s that it captured what it felt like—the way people dressed, the way they painted their houses.

Lubben: But why wasn’t that true in El Salvador?

Meiselas: El Salvador was darker because of the brutality of the military dictatorship throughout the civil war. People dressed that same way, but I didn’t feel the same spirit of—maybe optimism—in El Salvador. It was really a crushing place to be. Black and white definitely captured that mood better.

Lubben: Your use of color film turned out to be controversial: In 1981 when you published the images in Nicaragua, critics challenged your choice.

Meiselas: Photographs in newspapers were still in black and white, and color images of war were not yet familiar to people. Of course, now no one even thinks about this. At the time, I wasn’t taking a position in the debate about whether war should or shouldn’t be shown only in black and white. And I wasn’t responding to editorial pressures to work in color, as has also been suggested. I worked in color because I was responding to what I was seeing, and maybe feeling.

Lubben: Why did you decide to do the book? Were you responding to the way your images were used in the press?

Meiselas: With Strippers, the women and I were sharing a process. I was hearing them reflect on what their concerns were and how they saw the photographs of themselves. With the media distribution of my work in Nicaragua I had absolutely no connection at all to the process of selection, diffusion, and impact on peoples’ lives, or how they felt about it. When you ask the question, why did I do a book? I wanted to contextualize the work. It didn’t matter how many pictures had been reproduced in multiple magazines around the world. I wanted to bring them together in some way that would give coherence to my experience. At the same time, I was thoroughly aware that it was incomplete.

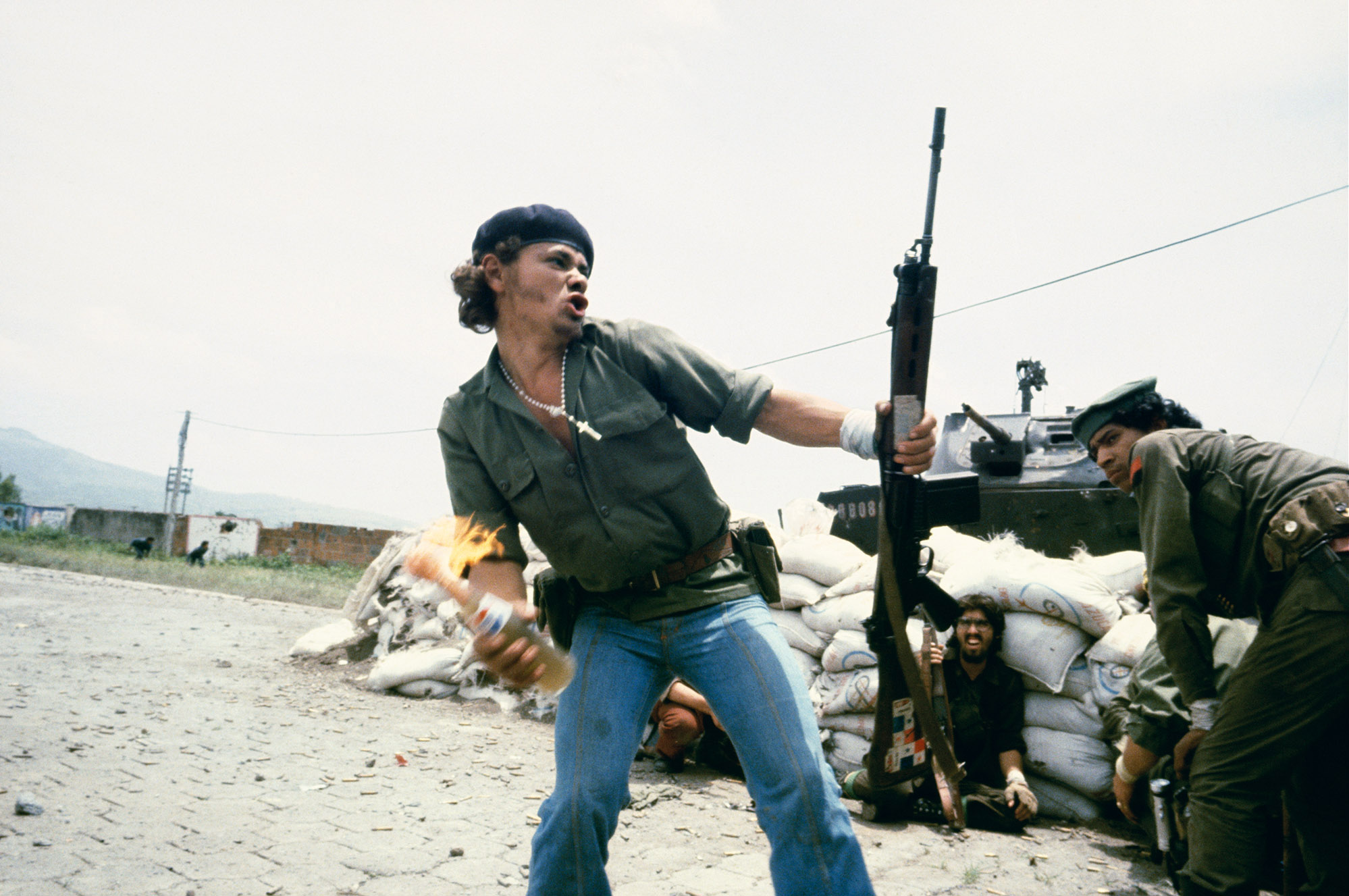

I continue to discover how pictures circulate, including in Nicaragua itself, where the images have often been reappropriated. One image in particular, known as “Molotov Man” [plate 64], appeared on matchbox covers, and then painted on walls. “Bareta,” the man in the picture, became a symbol for the revolution. Some images have separate lives. This one has now entered a complex debate about copyright and free use as well as who has the right to an image, including the subjects themselves.

Lubben: Two of your films about Nicaragua, Pictures from a Revolution (1991) and Reframing History (2004), both speak to your longstanding interest in returning to the scene and in repatriating your work. In Pictures, you went back to Nicaragua ten years after the revolution to track down the subjects in your photographs. What initially compelled you to do the film?

Meiselas: I became preoccupied with what had happened to the people in my photographs and wondered where they were and what they thought about the political shift in Nicaragua. It was something I thought about often, especially traveling between El Salvador and Nicaragua during those years of continuous civil war. Alfred Guzzetti and Dick Rogers and I had done an earlier film together in 1986, Living at Risk, about an upper-middle-class Nicaraguan family, but the stories behind my pictures of the insurrection had a more emotional center for me. Alfred had the idea for a more ambitious film of historical scope, consisting entirely of interviews, without a narrator. His model was Marcel Ophuls’s great documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, about the French Resistance during the Nazi occupation. I honestly didn’t feel I had the depth of knowledge to do that idea justice. My proposal was more modest.

Lubben: What was it like to talk to these subjects after all this time?

Meiselas: I especially loved the “search mode,” as we called it then, finding the people, which is best captured in the sequence of smaller and smaller roads that we traveled in order to find Nubia, the woman in the red dress. Her interview with all the kids surrounding her was particularly moving. She and I had shared a moment in time, and she remembered the conditions better than I did; she was carrying her dead husband in a wheelbarrow while bullets were flying all around us. It was a very special moment when she touched the same earrings she was wearing in the photo or pointed to the new shoes she had buried him with. She had a real sense of pride, having buried him all by herself—and at age fourteen!

Lubben: In your view, how was the film received?

Meiselas: I suppose we were initially surprised by the response, especially that many people wanted to see the photographs, not hear from the people in them. I am still fascinated by that schism between the aesthetic object—the “frame”—versus the lives that come forth from behind the photograph. Is it that we at times want the distance that a formal composition can give us or that we just don’t want to know or feel too much involvement? A frozen life in a photograph is perplexing for me . . . I suppose it’s part of the “going back” that I am often inclined to do. As much as I like the formalism, I am propelled to reconnect. I seek the feeling that comes from the connection. I think that moment of engagement is ultimately what sustains me as a photographer.

Of course time allows us to reflect. In the case of our film, perhaps we were too close to the time of those events; no one wanted to think about the failure of the revolution, and the Left wanted to simply blame the electoral defeat of the Sandinistas on the aggression of the US. The complexity of those years still needs to be reconsidered.

Susan Meiselas, Toward Sandinista training camp in the mountains north of Estelí, 1978–79

Lubben: You also made a film with Marc Karlin in 1985 called Voyages, for Channel 4 in England, in which you reflect on your role in Nicaragua through a series of letters to the filmmaker. At the end of that film you say: “I have pictures; they have a revolution.” In that poetic statement you seem to be finally moving on from Nicaragua, saying, in effect: “This is done for me; I’m no longer inside it. I’m now outside it.”

Meiselas: It’s a really strong line for me still. I think it was a painful acknowledgment of the limits of my work. Ultimately, I was as inside as an outsider can be, but you’re always an outsider. They had a society to build. They were going to start from the sidewalks on up; they wanted to transform everything. And I wasn’t going to be part of that.

If El Salvador hadn’t erupted, maybe I would have stayed longer. But my guess is that I would have started to feel I had a role somewhere else. It’s not to say I didn’t want to go back; I wanted to sustain relationships there but not stay. What I chose to do within the first year following the triumph was work with local photographers as they built the first newspaper. So I contributed in the ways that felt within the bounds of what I particularly could do.

Lubben: And of course you went back with your project Reframing History and transformed nineteen of your pictures into murals and hung them in public places, on the sites where they were originally taken twenty-five years before.

Meiselas: Yes. Reframing History came from a different process. I was digitizing part of my archive, and I was looking at all that work thinking, “Why bother to digitize it? What value do these pictures have, and for whom?” I thought, “Would they be of any value to the archives in Nicaragua? Is it of interest even to the people who were in the pictures twenty-five years ago, or the people who weren’t there but had heard about it?” That’s what led me to the idea of bringing mural-sized images back.

I found out about the Institute of History and started a dialogue with them. I also asked Carlos Fernando, my old friend, and Gioconda Belli, a Nicaraguan poet, if they thought my idea would seem appropriate to people there.

Ultimately, I collaborated with the Institute of History, who contacted the mayors of the four towns, and I chose nineteen pictures—symbolic of July 19, the day of the triumph over Somoza in 1979. Even up to the day that we arrived with the murals, it wasn’t clear if we were going to be able to put the murals on what had been the National Palace. Everything got negotiated—in each town, with each mayor, with each wall. You know the famous photograph on the cover? The man who lives in that house didn’t want the photograph on the wall of his house, so we hung the banner over the street. He was fine about that. He just didn’t want to have anybody mistakenly think that he was a Sandinista. There were other people who identified with the photographs. Ernesto’s mother was deeply honored, having the photograph of her son running across the street illuminated at night by a street lamp. There were many different kinds of reactions to seeing the murals, which we recorded on video; listening to the comments and watching people look at the images back in the landscape.

At that same time, there was also a film festival. It was really amazing for people because they had not seen any films from the 1970s into the ’80s. There were all these college kids who had heard about the revolution from their parents, and suddenly they saw images of Nicaraguans in the streets and realized they really missed out. It was like the people who felt they missed ’68 in our country.

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Lubben: In the 2008 edition of the book you included a DVD with the films Pictures from a Revolution and Reframing History; in this 2016 edition, in place of the DVD—now well on its way to becoming a defunct technology—you have introduced an augmented reality (AR) customized app, which takes the reader to short clips of the films that relate to specific images in the book. (Editor’s note: In this 2025 edition, the AR has been replaced with QR codes, the video clips are expanded, and the number of linked images has increased.)

Meiselas: The change in how we are including the films is both pragmatic and conceptual. I am curious to see if linking film clips closer to selected images will create the possibility for greater engagement. The idea of bringing together the original images with snippets from the films was one I first explored in exhibition installations, when I paired photographs with their corresponding section of the films in which people reflected ten years after the image was made.

Lubben: You also have chosen to use AR technology to link to a portfolio of previously unpublished images of life in Nicaragua in the years following the revolution.

Meiselas: Yes, the selection of those images was inspired by what Padre Ernesto Cardenal, the renowned poet and priest, wrote about during and after the popular insurrection, including the excitement and challenges of transforming Nicaraguan culture in the wake of the triumph. The photographs show small everyday moments, alongside the dramatic events of that year, and their hopes for a normalized life. The revolution was the beginning of a process—of reconstruction and remembrance—not the end. A series of these images appears as a little movie that can be accessed at the end of the Chronology section.

Lubben: How do you imagine that accessing a film clip by holding a smartphone over a still image in the book will change the experience of the films?

Meiselas: With the Nicaragua project, I have always been really interested in the way that history evolves, and the AR process enables a different way to look at that extending timeline and relate it back to the images. The risk with AR is that unlike with a linear movie, where you can capture your viewer and hold them through a narrative, you can’t do that with this more fractured approach. Through twenty short excerpts, we will be including about one-third of the film Pictures from a Revolution. How is that a fundamentally different experience? Will readers then be propelled to download or stream the full ninety-minute film? I don’t know.

I’m asking the reader to consider not only the specific timeframe of this book (1978–79), but to think about the broader concept of history unfolding, and how a photograph from a single moment in a person’s life shifts and our perception expands over the passage of time.

This interview originally appeared in Susan Meiselas: Nicaragua (Aperture, 2025).