Portfolios

A Celebratory Chronicle of Black College Life

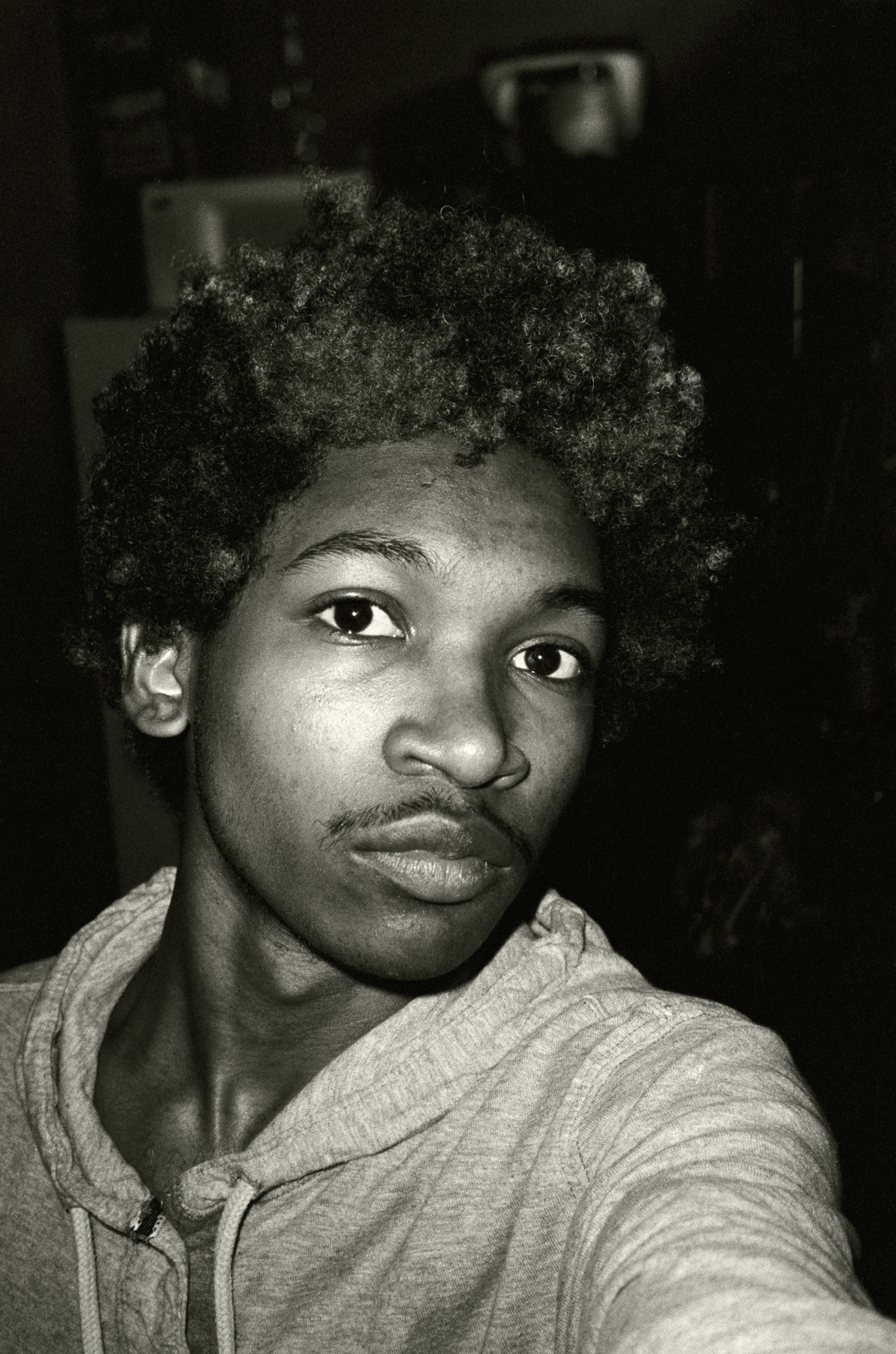

The photographer Adraint Bereal captures the agony and ecstasy of what it is to be a Black college student in the United States.

Adraint Bereal is in a tight spot.

He spent much of 2021 on the road, taking more than a dozen flights, plus Amtraks, buses, and rental cars. He lived out of his suitcase for months, lugging along eight cameras—point-and-shoot, Polaroid, medium-format, “everything you could think of”—until the weight of all that gear wore him down. He shipped all but two home and kept going.

Bereal’s mission was heavy enough: to meet at least one hundred Black college students across the country, capture their lives in images and words—preferably their own—and compile this material in The Black Yearbook, the second iteration of a project Bereal birthed in his senior year at the University of Texas at Austin. Returning from his travels, he faced another, more challenging task: meet a book deadline. He needed to pare down hundreds of hours of conversation, toss aside thousands of images, and cull from intimate human stories to produce a selection that his publisher, Penguin Random House, could present for mass consumption. The tightest spot of all is how to tell his and his peers’ stories “without cutting away so much of ourselves,” he told me recently.

Bereal’s first photography endeavors occurred when he was a teenager in Waco, Texas, taking iPhone pictures of his mother’s outfits before she went out. “It sounds so silly,” he says, “but that was practice for me. I was learning about composition, learning how to have a conversation with not only the camera but the person in front of it as well.” The Black Yearbook, in a sense, is an evolution of his earliest image making, equal parts archive and affirmation.

Bereal’s project started from a desire to help his classmates see themselves and celebrate one another.

Photography wasn’t much more than a pastime until one of his college professors suggested Bereal check out the work of Wolfgang Tillmans. “I went to the Austin Public Library,” he remembers, “and there was one image in particular.” Bereal later shared the image, Forever Fortresses (1997), which captures Tillmans holding the hand of his late partner, Jochen Klein, just hours before Klein died of AIDS-related pneumonia. “Seeing that image, photography as an art form, the power of images, finally clicked for me.” Aside from their demonstration of technical mastery, Tillmans’s photographs gave Bereal a portal through which to explore his own queerness, to see and understand himself.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

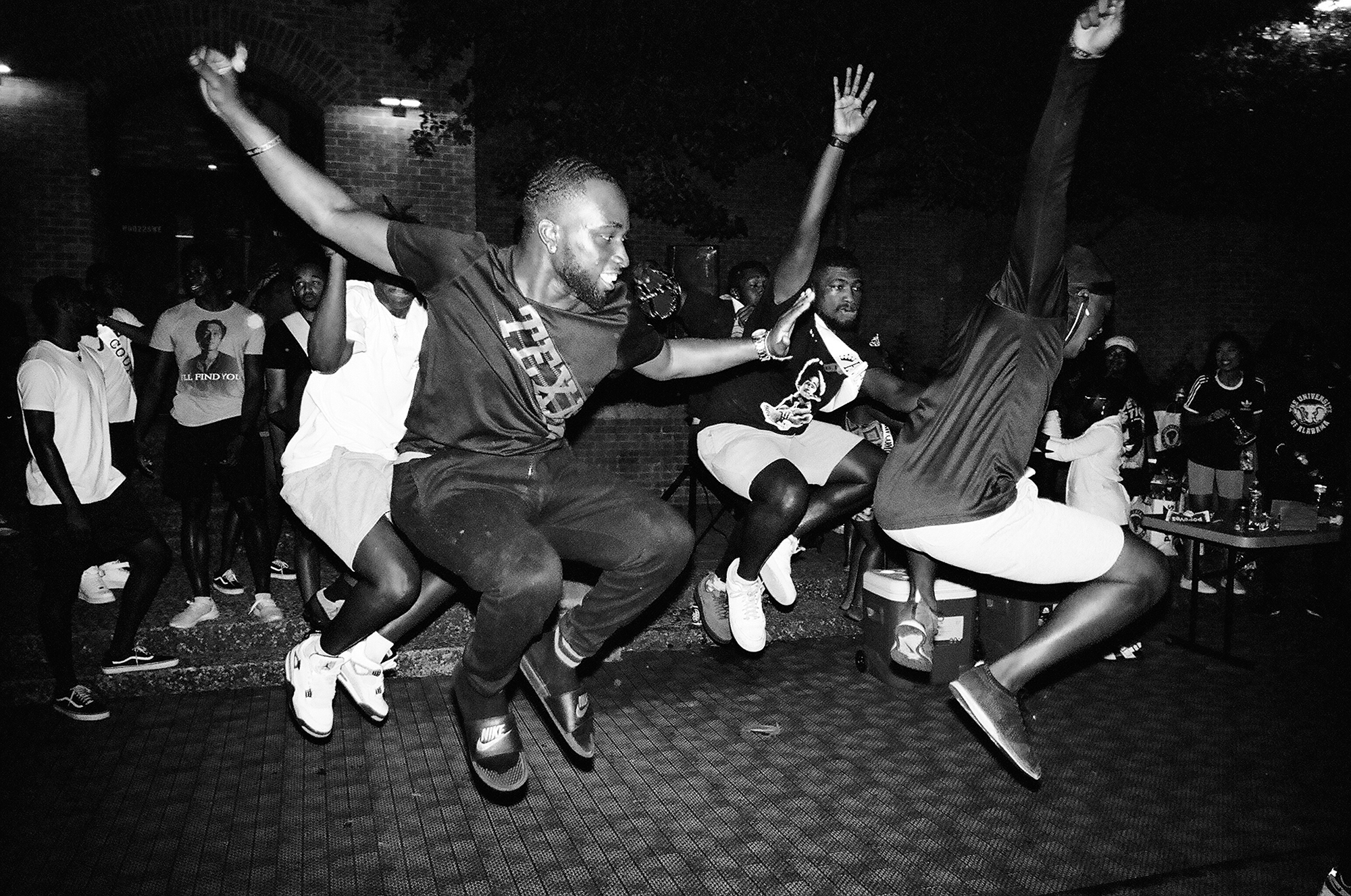

Images from homecoming at the University of Texas embody Bereal’s approach and illuminate the lives that fill The Black Yearbook. There’s one of the homecoming queen herself—flash galore, from the camera to her smile, her makeup highlights, her red nails, her glittering tiara. Echoes of the fit pic, with the patina of a 1990s family photograph. “I’m having a really voyeuristic moment,” Bereal says, “but I’m also participating in it, hanging out with my friends and just dancing with everyone.”

In Bereal’s practice, the photographer is comrade and chronicler, griot and visual artist. He walks the tightrope that stretches between the I and the we, engaging in the noble struggle to get the balance right and, most of all, to tell the truth, to capture the agony and ecstasy and in-between of what it is to be a Black college student today.

This kaleidoscopic hunger helps explain the variety in Bereal’s images. Starting from a foundation of portraits, he seems as drawn to the disposable-camera-esque candid as he is to the high-gloss, highly staged ad. He is a poet of the party scene—some of Bereal’s photographs call to mind the crowded, joyful abandon of Ernie Barnes’s iconic 1976 painting The Sugar Shack—as well as the selfie, which he considers “an affirmation of self,” recalling one of the positive things to come out of the COVID-19 lockdown. “When the pandemic happened, I spent a lot of time with myself. And it forced me to look in the mirror and say, ‘All right, this is who I am. I don’t always feel good. I don’t always feel pretty. I don’t always feel handsome. But I still love myself.’”

For Bereal, this love includes kindness toward himself and toward his fellow artists, whose development, he fears, might be stifled by the paralyzing effects of too-early criticism and the capitalist pressure to build a “brand,” if only because one has to pay rent and student loans, et cetera. “I’m still so young,” the twenty-four-year-old says, “and I really hope that people I respect give me the grace to grow and learn as an artist.”

Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”