Interviews

A Portrait of Ming Smith as an Artist in the Making

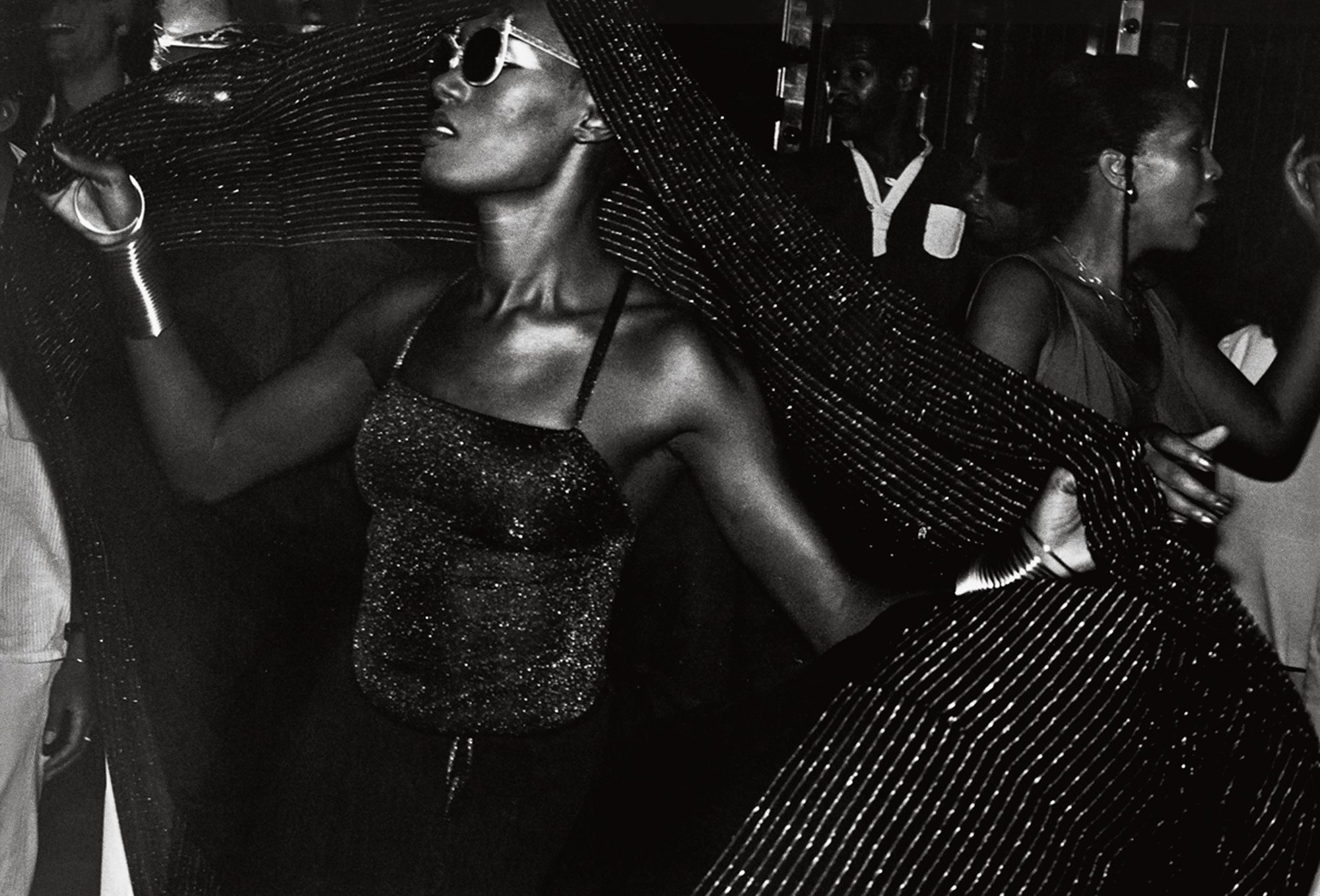

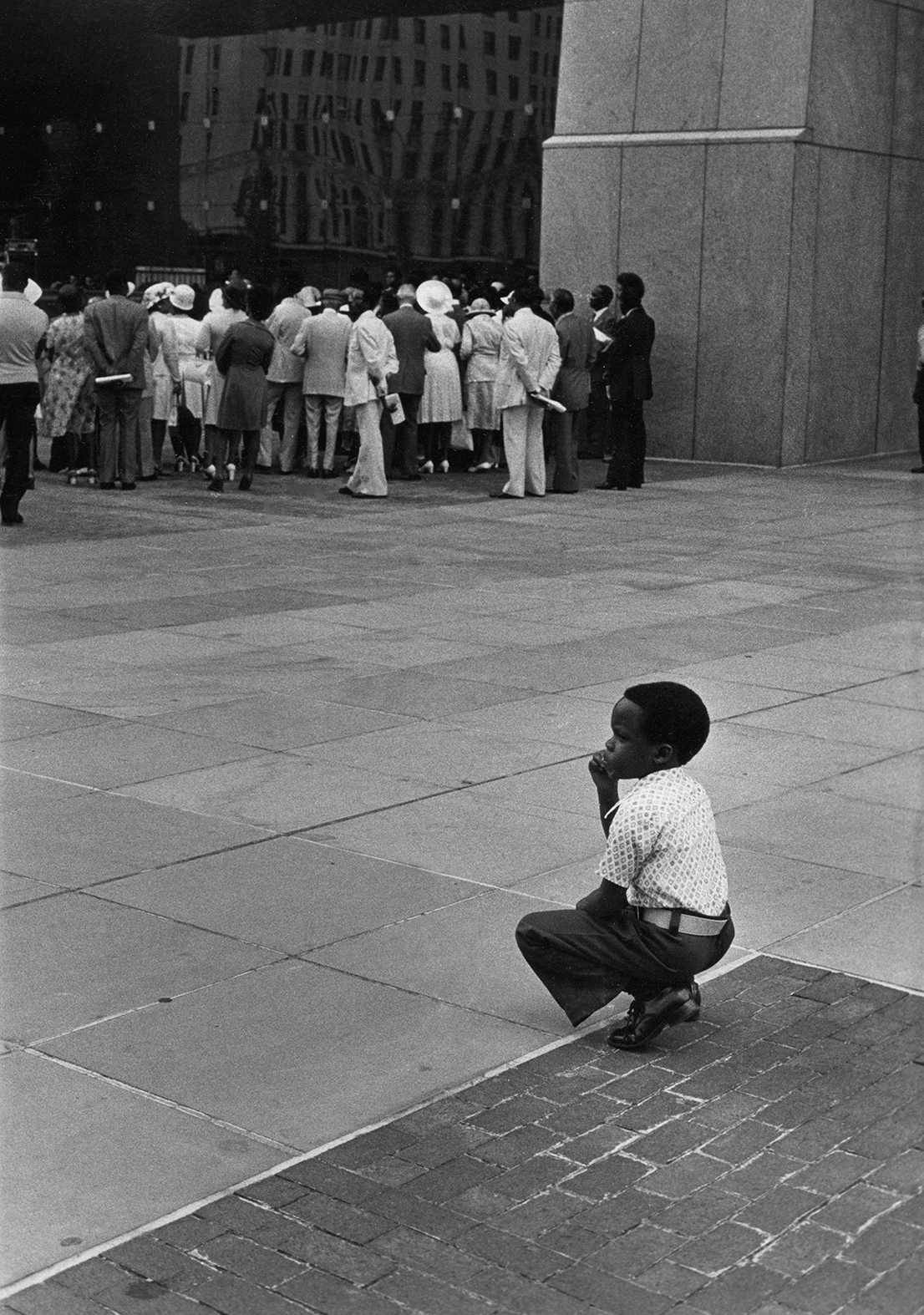

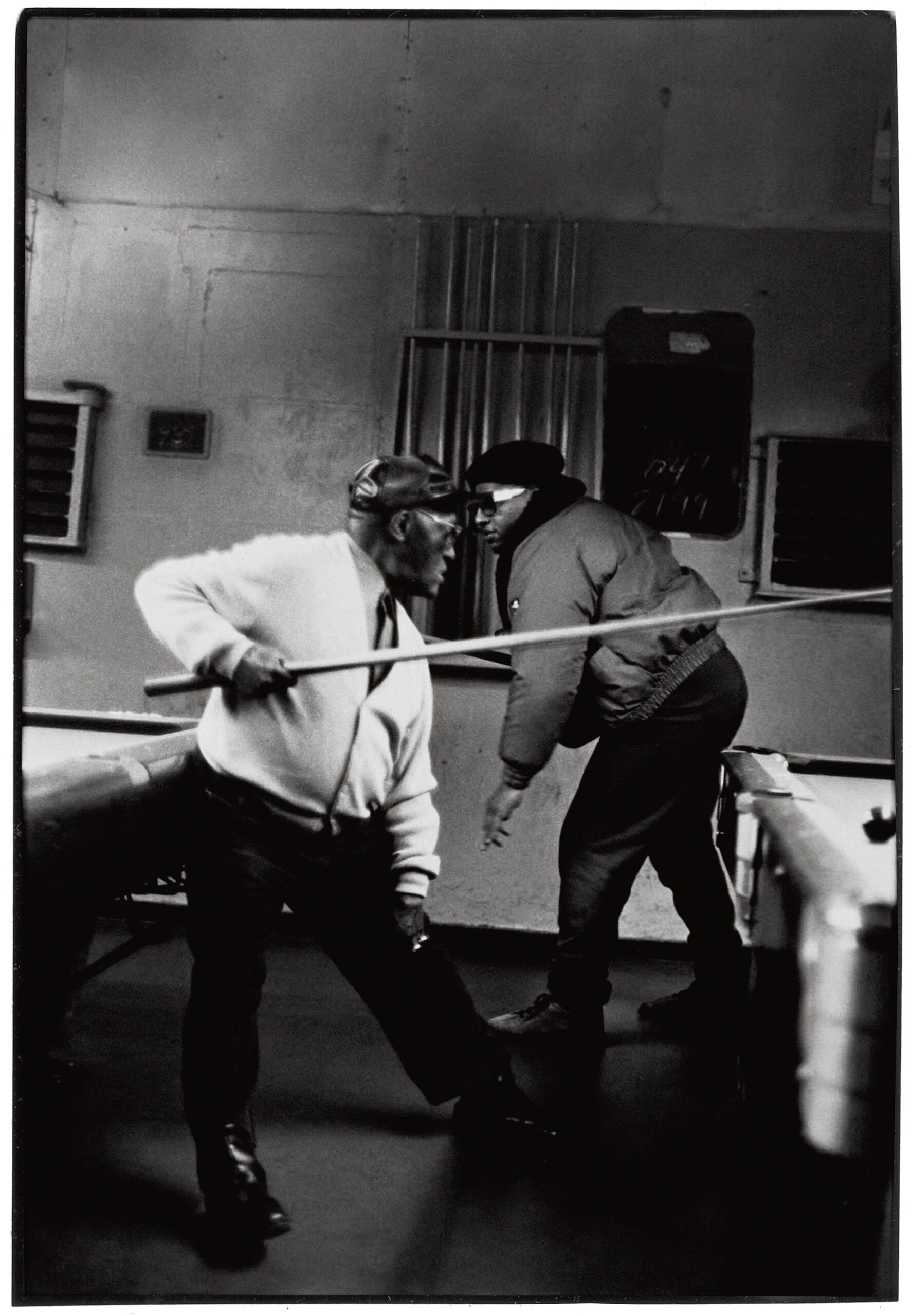

Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century Black life. In an interview, she speaks about her life and career—and the transcendent power of photography.

Ming Smith’s parents gave her a camera at a young age, and she fell in love with taking photographs. After college, she moved to New York to pursue a career as a photographer. In 1979, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, purchased several of Smith’s photographs, making her the first African American female photographer with that distinction.

Smith’s career twisted and turned in the following decades. In 2017, a retrospective at Steven Kasher Gallery helped start a renaissance, and over the next few years, interest grew in the US and around the world, including her inclusion in Arthur Jafa’s exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Serpentine Galleries in London. In 2020, Aperture and Documentary Arts published Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph. Since then, Smith has had a plethora of solo and group exhibitions, including the fall 2024 extravaganza that could be called “Ming-a-palooza”—four glorious presentations that took place in Ohio, where Ming grew up.

Over three days, two exhibitions opened at the Columbus Museum of Art: Ming Smith: Transcendence and Ming Smith: August Moon. Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts presented Ming Smith: Wind Chime while Ming Smith: Jazz Requiem – Notations in Blue was on view at the Gund at Kenyon College. Other highlights from recent years include the solo shows Projects: Ming Smith at MoMA and Ming Smith: Feeling the Future at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, and numerous group shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Paris Noir: Artistic Circulations and Anti-colonial Resistance, 1950–2000 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

In this interview, originally published in Smith’s Aperture monograph, we learn about the many ways in which Smith was a pioneer in photography, including being both the first female to join the Kamoinge Workshop, the Black photography collective, founded by Roy DeCarava and Louis Draper, and the first African American woman to have photos purchased by MoMA. Perhaps, most importantly, Ming talks about chasing the light—something she has done her whole career, and continues to do all over the globe, stealing away in free moments or rolling down a back-seat car window and taking photographs on the way to an opening. What fuels Smith is her unquenchable desire to chase the light until she has seemingly defied time, making it stand still, taking the shot that she sees in her mind’s eye, the shot that’s ready to share with the world.

Janet Hill Talbert: When did you first start taking photos?

Ming Smith: My dad earned a living as a pharmacist, but he really was an artist. He did watercolors, linoleum cuts; he carved wood sculptures. He made home movies, and he was also an amateur photographer. And, of course, my mother would join in and share his world. He bought my mother a camera, a Brownie, but she didn’t use it much. It just hung in the closet. So, on my first day of kindergarten, I asked her if I could take it with me to school, and she let me. I took photos that day and I carried them around with me for years, but I lost them somewhere in my move to LA.

Talbert: You were born in Detroit and grew up in Columbus, Ohio. Tell me about your childhood.

Smith: I grew up in a culturally rich environment. My grandparents met at college. My grandmother was a teacher, but in Columbus she wasn’t allowed to teach—Black or white students—I’m not sure if that’s because she was African American or because she was married. Although he went to college, my grandfather worked as a postman—which was one of the few good jobs Black men could have back then. He and my dad each owned their own homes, and there was great pride in the fact that the homes had garages, gardens, and vegetable gardens, all lovingly maintained. Every fall my parents would plant a hundred tulip bulbs in our yard; and every spring a riot of red tulips would bloom. My grandparents grew all kinds of things—pastel pink peonies, fragrant lilacs, fascinating morning glories, and green bushes called Juniperus x pfitzeriana. I remember crickets chirping, fireflies, train whistles, and my grandmother sitting on the front-porch swing reciting poetry—Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha”— along with my grandfather and other seniors, who would recite their favorite Paul Laurence Dunbar poem. My father also recited Shakespeare, “To be, or not to be . . .”—signifying nothing.

I was a quiet child, a loner—always in my own world. When everyone else was watching TV, I would be upstairs in my room alone, reading, drawing, coloring, making dolls, or outside jumping rope until the bats came out. But my grandfather was a breath of fresh air to me. He was the one who taught me about color. He was a postman, but he also painted the exterior of houses, and he had a thing about color. The colors he would paint on a house, on the trim, would delight him, and he would say to me, “Look at that color, really look at the color. Look at the whole house and then each part, each color.” I started to become aware of color, and color combinations. I became aware of different hues of color. I used to ask my relatives, “What’s your favorite color?” My father’s was blue. My grandfather and mother both liked red. My grandmother’s favorite color was yellow, and her favorite fabric was yellow dotted swiss, and that’s the name of one my photos. And when I married David Murray, a jazz musician, the fabric of my dress was yellow dotted swiss.

I loved my grandfather, and he’d always chuckle and say, “You’re my first grandbaby!” When I was about eleven, he took me on my first trip to New York, along with his youngest grandchild, a boy, as well as a daughter, who still lived at home. On another trip, he took us to the Paul Laurence Dunbar House in Dayton, Ohio. My grandparents weren’t wealthy, but they were aristocratic in nature. Education and culture were important to them, and that’s why I was going to be a doctor, because that was my grandfather’s dream for me.

Talbert: You mentioned your early photos and drawings—do you still have any of them?

Smith: My mother was constantly throwing things out because my dad was a “collector,” so when I went to college, she threw away my drawings, and even some awards I’d won. I thought she’d thrown away everything, but after she died, we were going through her things and I found a box that said “Ming”; it was an old Kodak photo box, and it had a few of my early photos. Inside, I found a photo I’d taken of some girls who were my classmates. I was about ten, and we were in Columbus, Ohio. My mother also saved some photos that I’d taken while I was in college at Howard. One weekend, a friend and I had driven to New York and I took some photos in Washington Square Park. I would have completely forgotten that excursion if my mother hadn’t saved the photos. One’s pretty good, so I’m glad she saved them.

Talbert: You went to Howard University in Washington, DC, and you were pre-med and graduated with a BS in microbiology. At the time, Howard only had one photography class, and you took it.

Smith: I was always taking photos, so I took Howard’s only photography class. One day, I asked the instructor if I could earn a living doing photography, and he said that I could be a medical photographer, or I could photograph machinery. That was it. Those were the two options, and neither of those things appealed to me. So I was kind of lost, but I was still passionately taking photographs. At one point, I met the campus photographer, who said he would process my film for me. I gave him about a hundred rolls of two-and-a-quarter film, but I never saw the film again.

Talbert: After Howard, you moved to New York and became a model to support yourself. There are lots of misperceptions about you and your career, and I think it’s important to establish the fact that you weren’t a model who became a photographer, but a photographer who supported herself as a model.

Smith: I didn’t call myself a photographer, but I was constantly shooting. I was also dancing and modeling, but I didn’t define myself as a dancer or a model. I was just a young person in New York trying to find my way, and I had to support myself, so I took a job as a model. August Wilson worked as a dishwasher, and many other people take jobs to support themselves while they’re pursuing their art.

Talbert: Nevertheless, because you were a model, and a beautiful woman, it seems that society assigned labels to you. In 1973, you joined the Kamoinge Workshop, a New York–based group of photographers. You were the only woman in the group. In the 1973 Black Photographers Annual, the first publication in which your photographs appeared, a text noted that you had started taking photos the year before, when in reality, you had been shooting since you were five. Can you talk about how you got into Kamoinge?

Smith: I was on a modeling job and I was sent to Anthony Barboza’s studio. As I was waiting in the foyer, I overheard some men talking—or rather, debating—about photography: was it an art form, or was it just nostalgia? I was fascinated. Every time I went to Barboza’s studio, I learned a bit more. Barboza was a commercial photographer, and people used his darkroom, so there were people coming in and out all the time. It was a meeting place, a hub of creativity. And that’s how I met Lou Draper and Joe Crawford. Lou was the one who invited me to join Kamoinge, and Kamoinge was my introduction to photography as an art form. That was a major awakening.

Talbert: Kamoinge gave you a framework?

Smith: Yeah, it let me know that there were fine-art photographers out there. There was a lot I didn’t know. I didn’t know about Roy DeCarava, one of the pioneers who got together and started Kamoinge in 1963. When I joined in the early ’70s, I did some research, and it seemed logical that these men, this group of Black male photographers, wanted to take control of their own images—their humanity—and not see stereotypes, or someone else’s propaganda about them. That was radical.

Talbert: It was also radical that you were the first woman to join Kamoinge.

Smith: People ask me, “How did it feel to be the first woman in Kamoinge?” But I never dealt with that at all. I just never dealt with it. I was just an artist, a photographer. And I think that within any profession, the way you carry yourself has a lot to do with everything. Everything.

Talbert: So what did you learn from Kamoinge?

Smith: Kamoinge was about the critique, but I also learned about lighting. I learned about W. Eugene Smith, even though I had seen a few of his images before. Lou worked for him; he used to print for Eugene Smith. So Kamoinge opened up the entire world of photography for me.

Talbert: Kamoinge was about both critique and technique?

Smith: Yes, and a few other things, like setting up group shows. But the main thing was, you would bring your work and put it up on the wall and everyone would critique it. And they could be really cold—cold-blooded. I remember the first time I showed one of my photographs, someone said, “I don’t see that there’s anything to that photo—it’s just a photograph of a baby.” That was my first critique. But Lou Draper was the one who said that I was a really good photographer; in fact, he’s the reason why I had a show at Kasher (Steven Kasher Gallery retrospective, 2017). The first time I went to Kasher Gallery was to hear Lou Draper’s sister. She was giving a talk connected to Lou’s posthumous 2016 exhibition. I got very emotional while she was talking, because I loved Lou. He was a humble, kind, and nurturing man.

At Kamoinge, I also learned about printing, and what type of paper to use. I printed in college, but I didn’t know a lot about print quality. So I developed my sense of what I wanted the print quality to be. Technique is important, you have to have tools to build a craft, just like with acting or dance. It’s really about the artist and what they do with their tools. Because there are some folks who are fine technicians, fine photographers, but I’m not moved by their work.

Talbert: Did Kamoinge give you a sense of community?

Smith: It was a community, but eventually I didn’t really hang out with them. I was too much of a loner. I didn’t live in Harlem. I lived in the West Village. I had another life because I was modeling, so my friends were mainly in that industry—fashion designers, other models. But I wasn’t really deep into either of those lifestyles. When I was living in the Village, I became friends with photographer Lisette Model and her husband, Evsa. Lisette taught Diane Arbus. I learned about Katherine Dunham, and I started to dance. I learned about ballet mistress Syvilla Fort. So I was in a lot of different worlds. I liked to poke my head in and poke my head out—kind of like what I do with my lens.

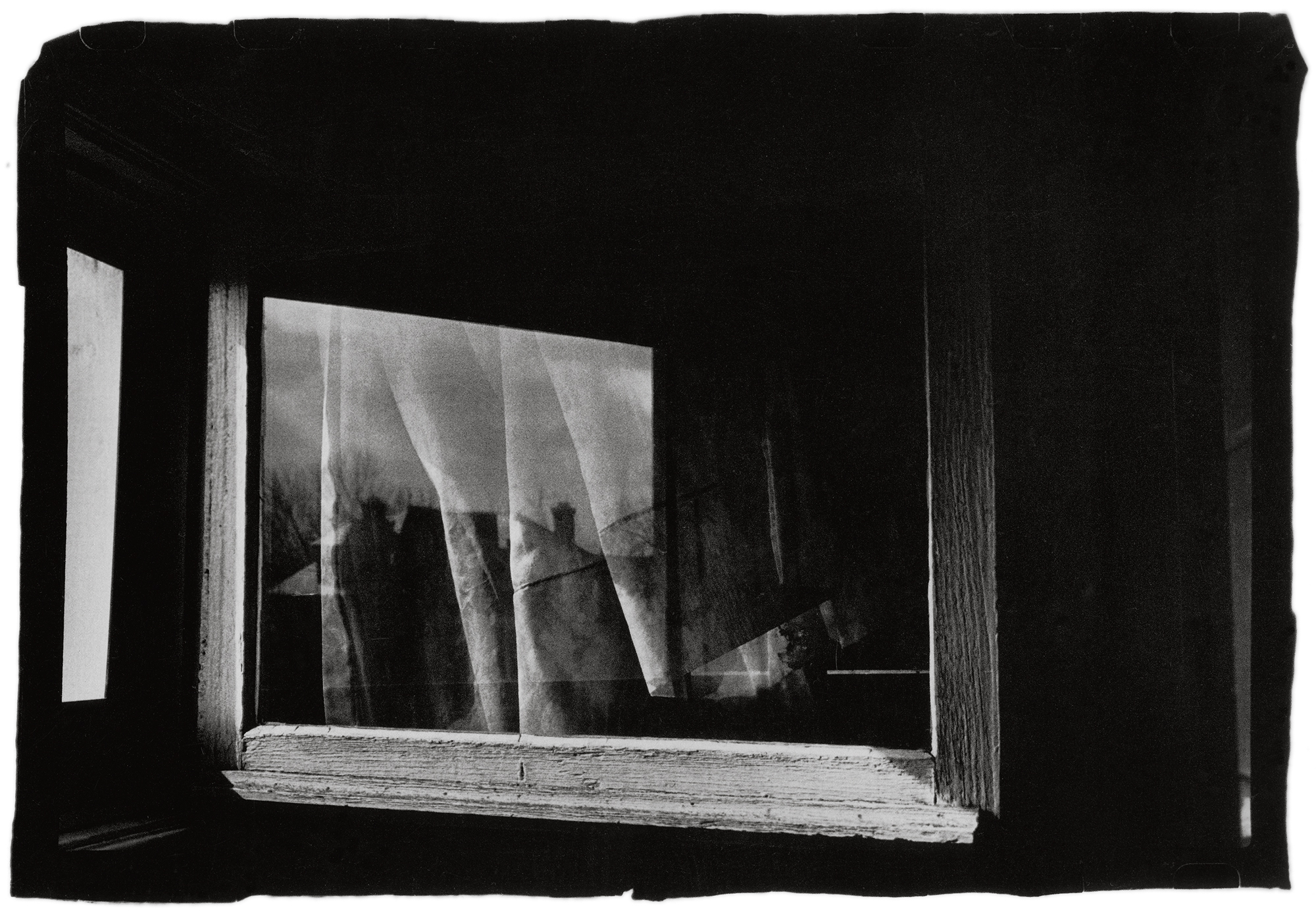

Talbert: Many of your photographs have a lyrical, dreamy quality. One of your early images is called The Window Overlooking Wheatland Street Was My First Dreaming Place (1979). What were you dreaming about back then?

Smith: When I was a kid, I was a good student, but my teachers would frequently say on my report card, “She’s always daydreaming,” or “She daydreams too much.” But I loved school. I loved being away from home.

Talbert: Why?

Smith: My father was really strict, critical, and he had high expectations. He was a very disciplined kind of person. I wasn’t relaxed around my parents. At a very young age, I saw a lot of pain in people—in my father, in my mother, in my family.

Talbert: Do you think that taking photographs was a way of escaping that pain, or releasing it, or processing it?

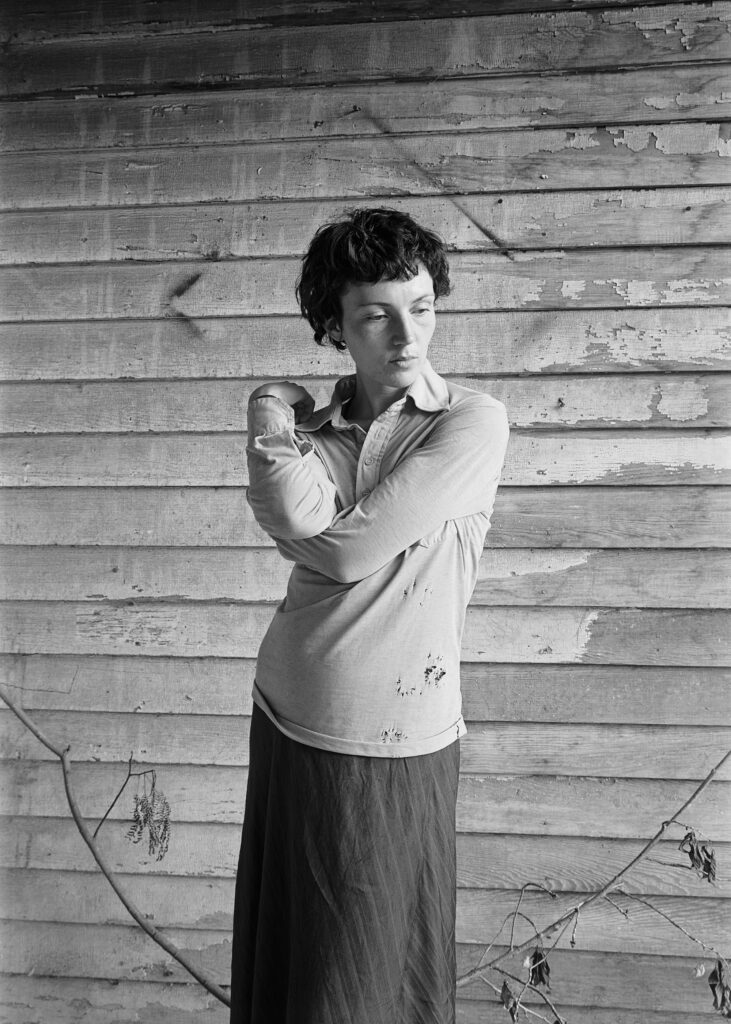

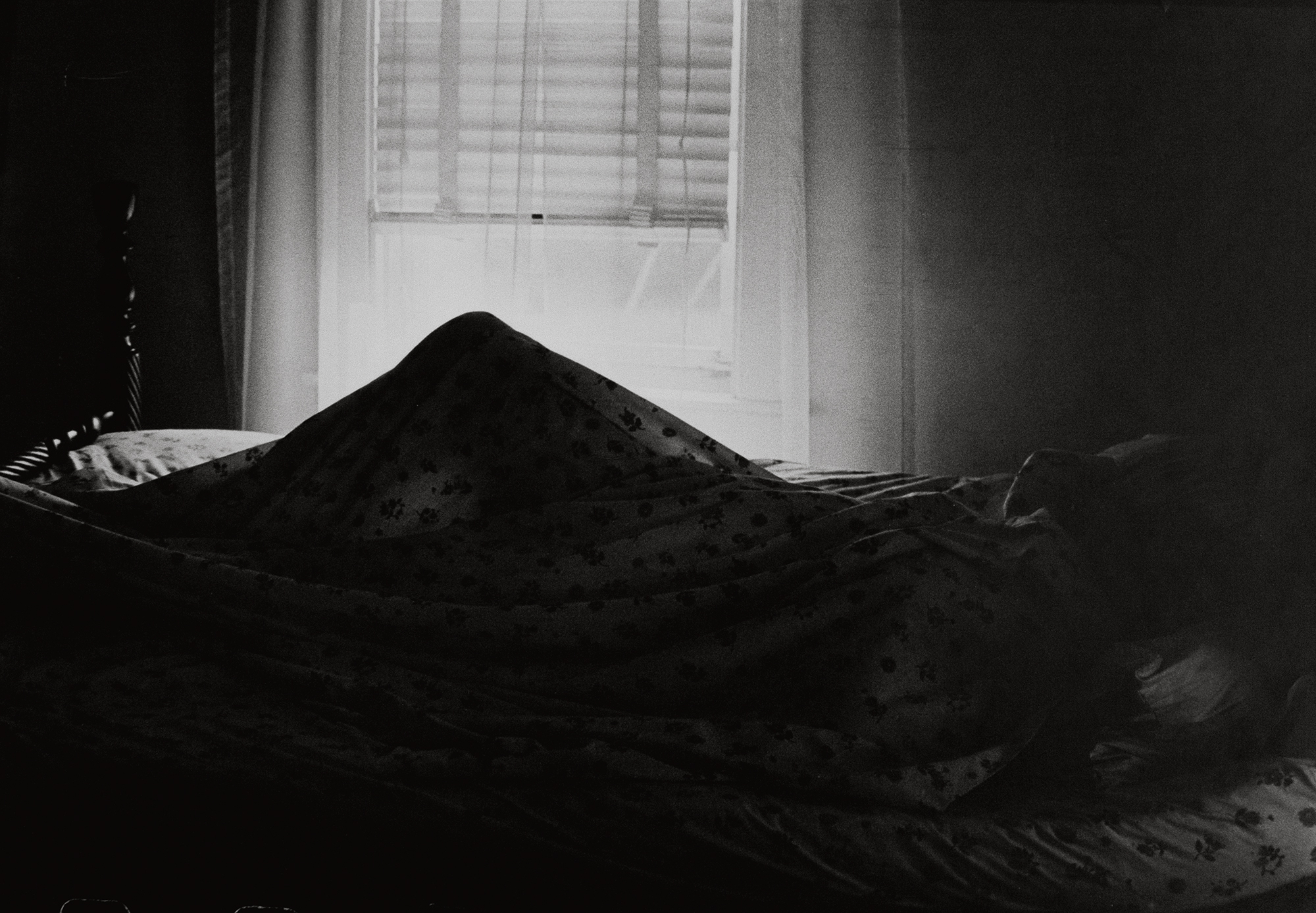

Smith: I guess it was just a way of . . . surviving. My aunt suffered from depression. In one of my photos, Aunt Ruth (1979), she’s in bed but you can’t see her; you only see her form under a sheet. But just seeing her in bed with the covers pulled over her head, that could represent all kinds of feelings of depression, oppression, fear, and the doubts in myself—things I’ve experienced. But because I can look at the photo, I am reminded of the pain, acknowledge it, but also keep moving.

A lot of women in my family were very strong. They were rebellious, they were definitely feminist in their own way, and many didn’t ever fit in. They were on the outside. So there was a lot of pain. And I was aware of that, because not only did some not fit in, some didn’t survive, and it seemed to me that their lives were tragically wasted. One committed suicide. Another was in and out of a mental institution. And others suffered nervous breakdowns. A lot of the women were very, very smart, and they weren’t just going for the “okeydoke”—meaning what was expected of them or acceptable at the time. Yet they didn’t survive.

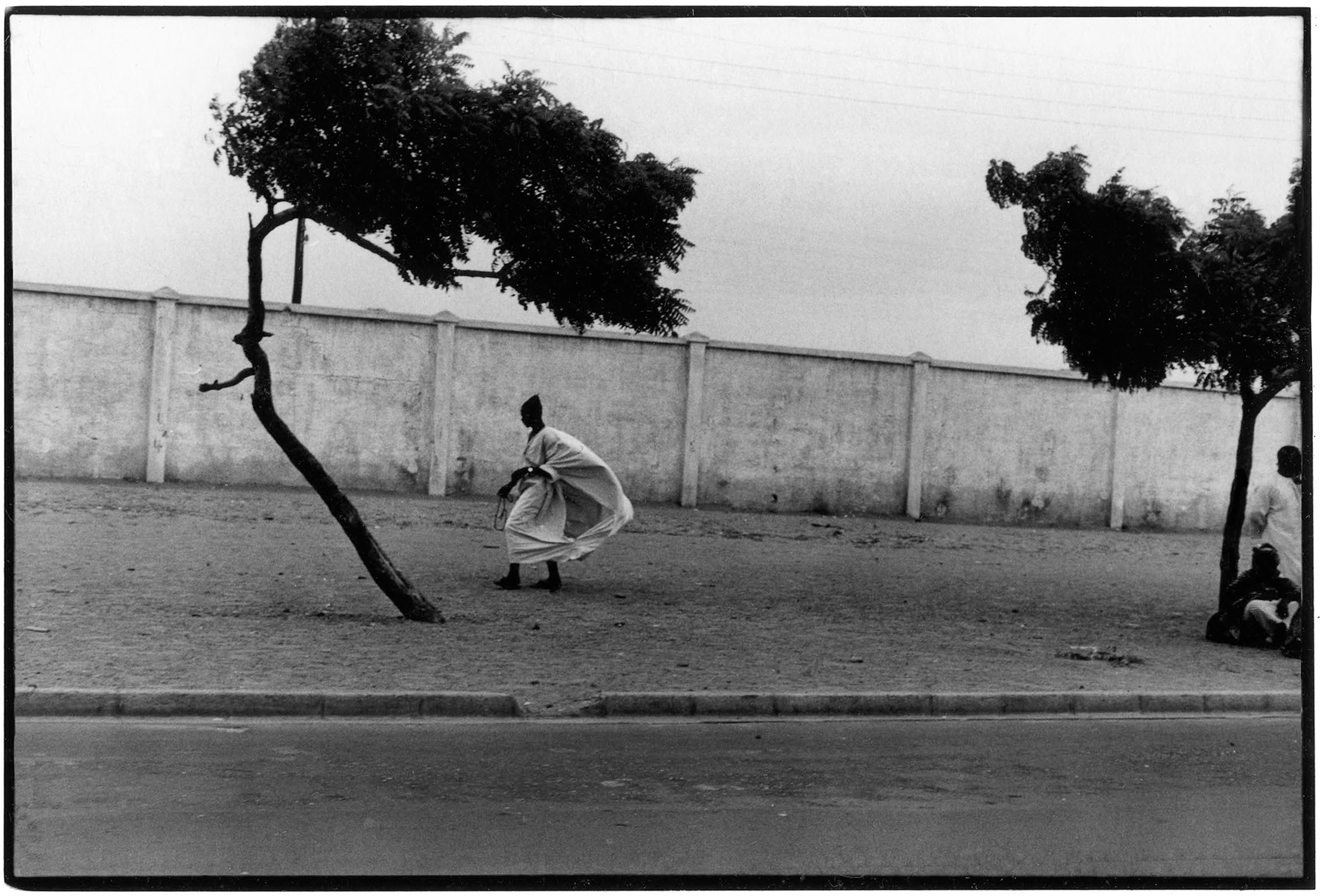

Dakar Roadside with Figures, Senegal, 1972

3000.00

$3,000.00Add to cart

Talbert: That’s powerful. You’ve talked about survival before. In your conversation with Arthur Jafa connected with his 2017 exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions, which featured your work almost like a solo show, you mentioned the importance of thriving, and not just surviving. Some of your female relatives didn’t survive, but you survived through photography.

Smith: Part of getting through life is riding the tides. It takes effort, and I’m glad I kept going. When I was premed, I didn’t want to be a doctor. I was constantly taking photographs, but I never told anyone I had dreams of becoming an artist or a photographer, even when I came to New York.

Talbert: When did you finally declare yourself an artist?

Smith: When I started getting my first paycheck! [Laughs]

Talbert: What was your first paid job as a photographer?

Smith: Well, it wasn’t really a paycheck, but in 1979, when the Museum of Modern Art purchased two of my photographs (David Murray in the Wings, 1978; and Christmas Constellation, 1978), that was a validation. I thought my work was good—this wasn’t egotistical, because the conversation was between me and my work, no one else. But it was great to be validated by having your work purchased by a major institution.

Talbert: You were the first African American woman to have your photographs acquired by MoMA. How did that happen?

Smith: One day I was passing MoMA and I remember saying to myself, “I’m going to be in there one day.” I didn’t dare say it to anyone. Sometime later, I heard that they had an open call and you could drop off your portfolio on a certain day of the week. On the day I arrived, the receptionist thought I was a messenger—and she treated me like one. When I went to pick up my portfolio a few days later, the same receptionist told me to have seat, because the head photography curator, John Szarkowski, wanted to meet with me. The curator Susan Kismaric escorted me into a room where eight of my photographs were placed on a tabletop. Kismaric said that John loved my work, but they could only purchase two for their collection, and she made me an offer. It wasn’t even enough to cover my expenses—and I told her that. She said, “What! People try to give us work!” She couldn’t believe I wasn’t happy and was hesitant to accept the offer, but she gave me the weekend to reconsider. When I told my husband, he said take the money.

Talbert: Let’s talk about your technique.

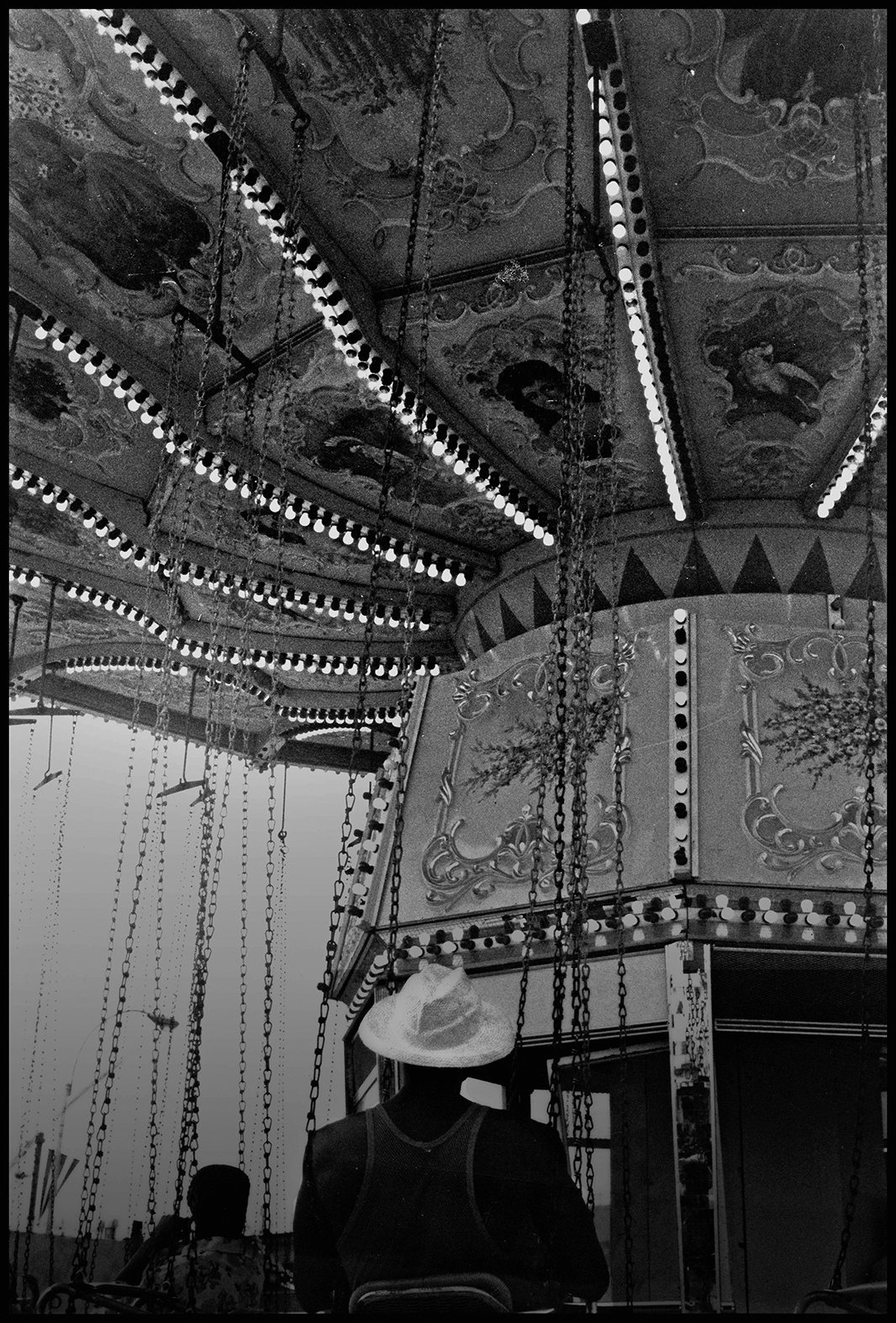

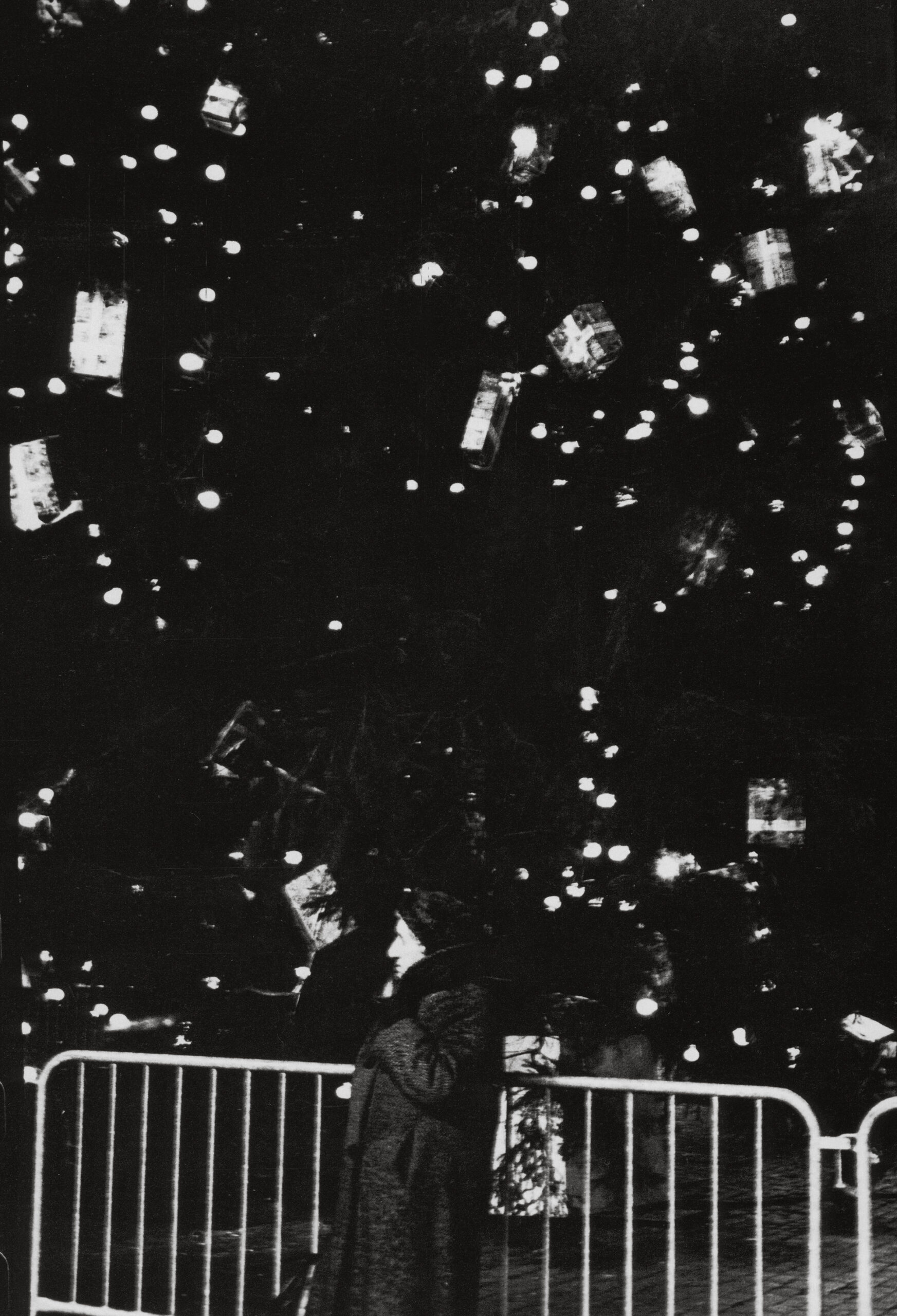

Smith: Dealing with light is the main focus and attraction. I do a lot of night shooting, and even in the dark, I look for the light—the way light comes in. In all my work I improvise with light, with what’s there. I feel my way through things, and I let the spirit guide me. When I’m shooting, I usually have a sense: “This is the photograph that I’m going to print. This is the moment.” I kind of always sense that, but I continue to shoot anyway, because a lot of times you’re just shooting and grabbing moments—so you don’t really have time to do any editing in your mind, but sometimes you just know, “This is the shot.”

Talbert: It’s a feeling that you have?

Smith: Yes, a feeling, and that’s the turn-on for me—photography is about the discovery. After the photo is printed and I look at it, I can define or refine the image in an artistic way. But basically, when I shoot there’s a moment that is the moment, and you kind of know that you have a good shot, at least I do.

I like catching the moment, catching the light, and the way it plays out. Because you can be focusing on an object and you know you have to hurry up, because a cloud may be coming. You know how the sun comes in and out because of the clouds? The image could be lost in a split second. I go with my intuition.

Talbert: Who are some of your influences?

Smith: Katherine Dunham, of course, and Zora Neale Hurston. Romare Bearden is my all-time favorite. But I would also say Monet, Chagall, Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, Matisse, Roy DeCarava, Lou Draper, Gordon Parks, Lisette Model and Diane Arbus, Brassaï, W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, Deborah Turbeville, Sarah Moon, and on and on and on. And, of course, some of the Kamoinge members.

Talbert: Cartier-Bresson said, and I’m paraphrasing, that photographers deal in things that are continually vanishing.

Smith: It’s just being in that moment. You can’t be so much in your head. That’s why I like dance too. You have to be in the moment, you have to be right there—it’s like a form of meditation.

Talbert: What’s the relationship for you between dance and photography?

Smith: It’s about always looking at lines and the quality of the movement. It’s about seeking energy, breath, and light. The image is always moving, even if you’re standing still.

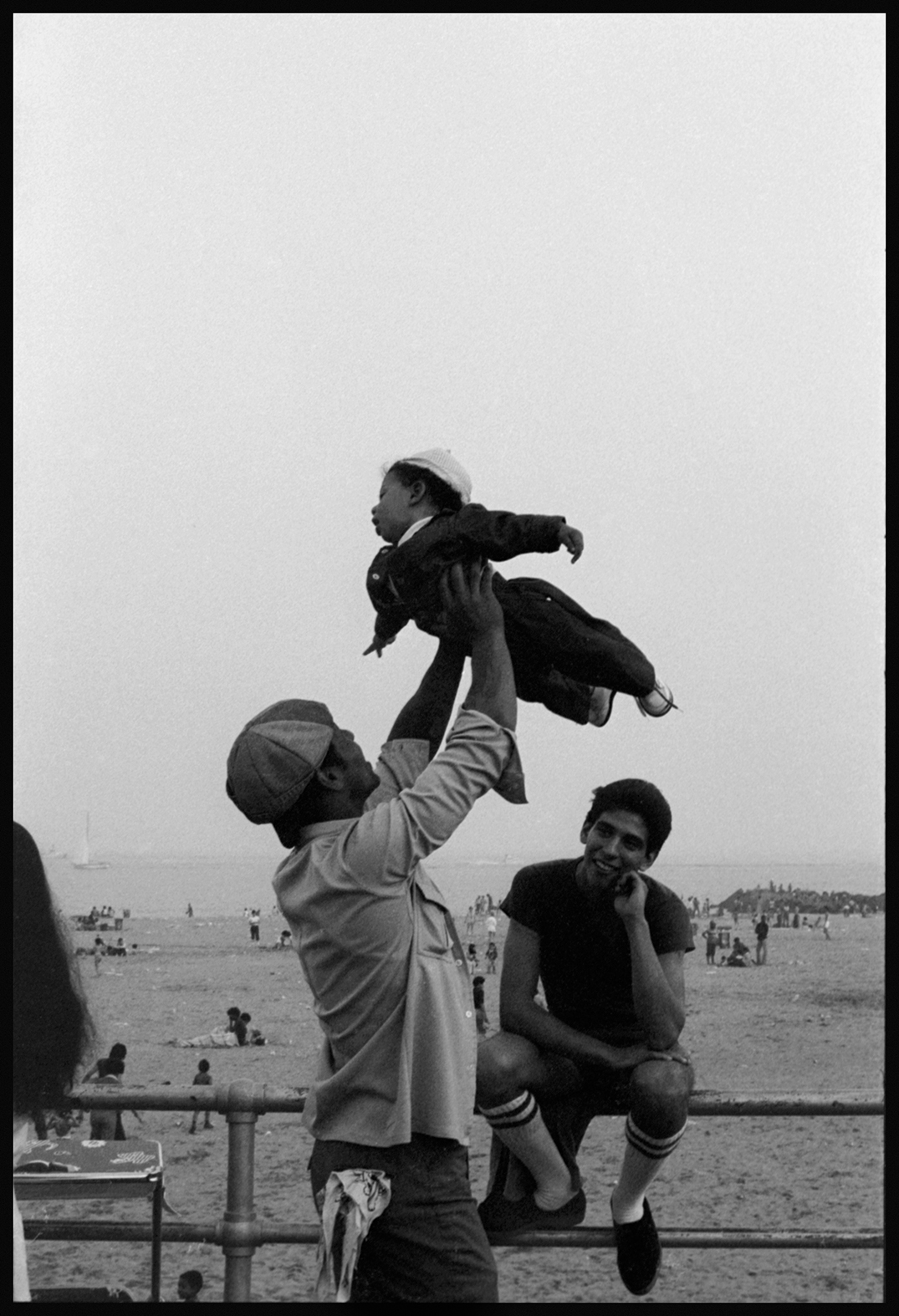

Ming Smith, America Seen through Stars and Stripes (Painted), New York, 1976

Talbert: You use many prost-production techniques, like tinting, painting, and collage. Why did you start painting your photographs?

Smith: Visually, I just wanted more. The quality of the image is the utmost important thing to me. So if I saw an imbalance in some way, I would apply paint. I didn’t want to throw away a print, but instead I wondered, “How can I make this better?”

The jumping-off point for a painter is the blank canvas. For me, the print became the blank canvas, and I wanted to explore. I wanted to see what I could do with that. I first started tinting my photos in the ’70s, but I didn’t know why. And then I remembered that my mother had had a job hand-tinting photographs. My father was furious, because I chose to go to Howard University instead of Ohio State—he would not give me a nickel, even though I was on a full scholarship. So my mother—who did beautiful embroidery—learned to tint photos from a neighbor and would slip money by mail to me to help me out while I was in college.

Some people like my photographs better with paint, some don’t. I like them both. Usually if I show a photograph, then it means I like it. Like America Seen through Stars and Stripes (1976), with the blood-red paint. That’s a good photo, but the paint adds more to our story—Deborah Willis uses the word “enhanced” when talking about my painted photos, meaning that the paint adds to the original image. The red paint in America Seen through Stars and Stripes emphasizes even more the violence that was done and is still being done to Black people. My Aunt Stella had an expression that she would use from time to time, and I remember her sitting in a chair and saying, “The things I’ve seen America do. The violence that I’ve seen them do to us . . .” She was referring to Emmett Till and moments like that. She never really said specifically, but when she said that statement, I felt it. So America Seen through Stars and Stripes comes from the feeling that I had when she said that.

Talbert: You frequently use double exposure in your work.

Smith: I had a photo of James Baldwin. I didn’t want a mediocre photograph of him, because he’s grand. He’s huge. Genius. He’s one of our most beloved icons. The same with James Van Der Zee. So I thought, Why not put them in the skies of Harlem? Because Baldwin and Van Der Zee are a part of who we are as a people. They are part of us, part of Harlem, part of our ethos.

Talbert: You were married to jazz musician David Murray, and music is important to you and your work. You’ve made photographs of musicians and entertainers. What was your introduction to jazz?

Smith: I had an older cousin, Eugenia, who I was very close to. She was brilliant. She had a pharmacy degree and a doctorate of psychology. She was so good to me. Eugenia’s style reminded me of Lorraine Hansberry. One day when I was about twelve, we were riding in her car from Detroit up to Ann Arbor, where she lived, and a song came on the radio. When I asked her, “What’s that?” she said, “That’s jazz.” And later another song came on and I said, “What’s that?” and she said, “The blues.” Then she asked me, “Which do you like better, jazz or blues?” And I said, “The bluuues!” drawing out the word. And she just laughed, but it was also a way of affirming me, like, “This girl is smart, she’s hip, she knows! She knows what’s going on.” But it was true! I really love the blues.

I think photography is mystical, spiritual, magical. It really is.

Talbert: How would you say the blues informs your work?

Smith: If people could feel what I feel when I hear a Billie Holiday song—that’s what I would want them to feel when they look at my work.

Talbert: You’re largely self taught; how did you learn?

Smith: I took photos. I photographed. If a writer wants to write, they’ve got to write. If someone wants to paint, they’ve got to paint, right? It’s in the doing of it, the repetition of it. Then the conversation is between your work and you. It’s not about anybody else. It’s just you and your work. That’s the way to develop as an artist. The answers are not on the outside. Part of me sticking with photography is that I could look at my work and see if it was good or not. I didn’t care what anyone else said. In modeling and dance, there was always someone scrutinizing me, but with my photography, I held myself to the highest scrutiny. I decided if my work was good or not.

Toni Morrison was a mother, and full-time editor, and she would get up early in the morning before she went to work—three or four hours early—so she could just write. She had commitment, discipline. She was discovering herself as a writer. It’s the discovery, the exploration of being an artist and doing the work. That’s the essence of it: your voice or your vision must come from you. It’s in the doing of it. It’s the trip along the way. That’s where the real work is. That’s when the talent comes through.

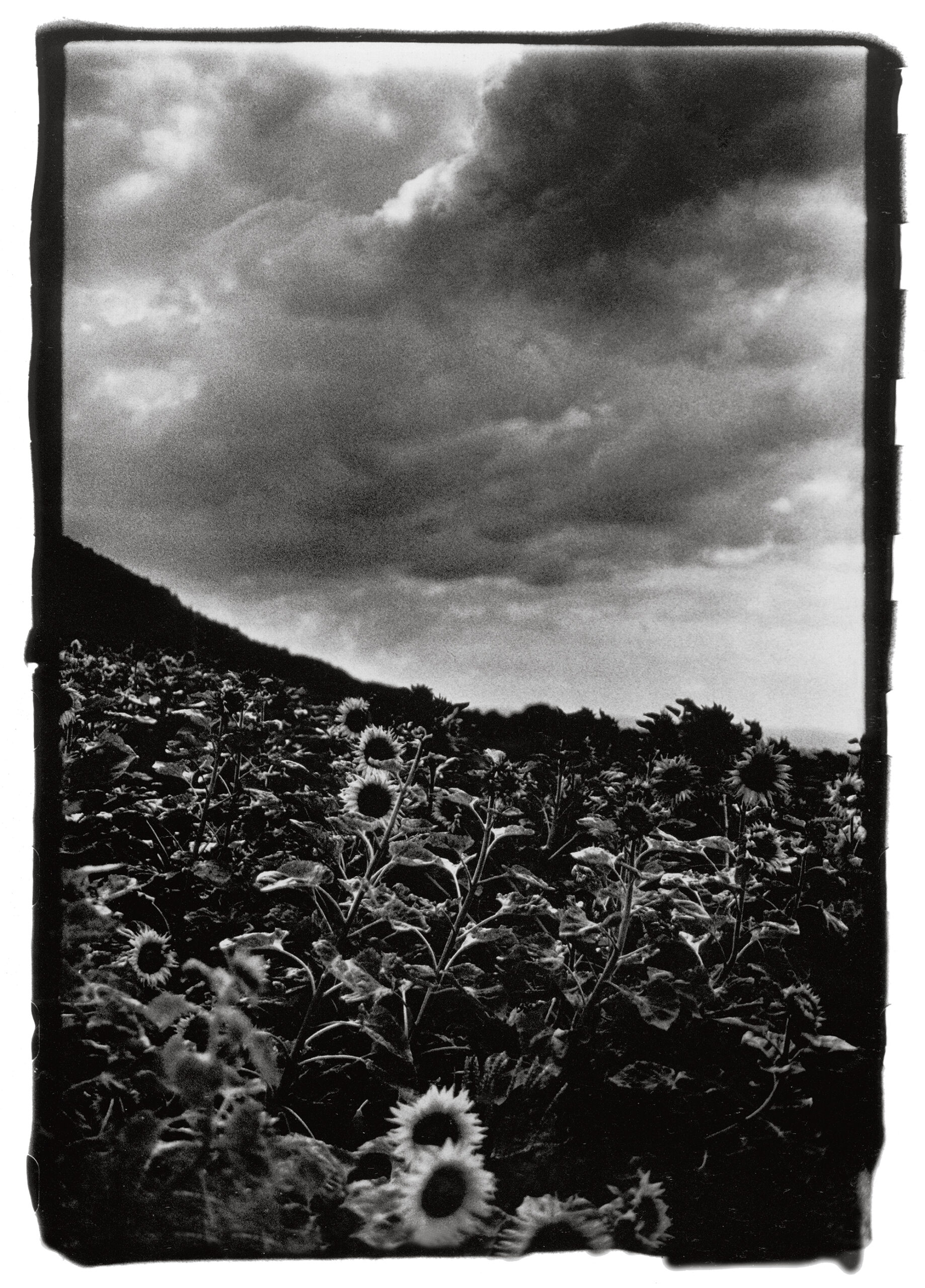

Talbert: There’s a tendency to pigeonhole African American artists into particular locales, but you’ve traveled extensively and taken photos around the world. In a sense, you’ve chased light in many places on the globe. Can you talk about your photo Goghing with Darkness and Light, Sunflowers (1989), about the light on that particular day?

Smith: In 1989, I was in Germany traveling in a van [with the David Murray Octet] and my sons, Kahil and Mingus. We were passing fields and fields of sunflowers and I said, “Excuse me, we’ve got to stop! I just need to take this shot! Give me two minutes. I just need to stop and take this photograph.” And they did stop, because we’d been traveling for twelve to fifteen hours, and for me to ask one time to stop didn’t seem too much to ask. I was used to doing my work on the side, or in between. But when I saw that field I thought, “Of course, van Gogh is going to paint sunflowers because that field of sunflowers was the most beautiful scene.”

Talbert: How long did you stop?

Smith: I jumped off the bus and quickly took some shots, and that’s why it’s called Goghing with Darkness and Light, because we were on the go, and the sky was heavy with clouds, just like van Gogh’s light.

Talbert: Do you have any other moments like that that you remember vividly? Moments that you absolutely had to capture?

Smith: Years ago I was in Japan, again traveling with David, and I saw dewdrops on a tree and a full moon. It had been a full day. My husband and I had taken our son Mingus to the Japanese Disneyland. We had been in the studio with David. And now it was early evening and it was starting to rain. We’d been out since about seven o’clock in the morning, plus we had jet lag. I said, “I want to shoot this tree.” And David said, “O, no, do we have to stop?” And Mingus said, “O, Mommm! Do we have to?” [Laughs] We were very close to where we were staying, maybe a half a block, and I said, “Just go; go home.” So I stopped and took the photograph. I was tired, I didn’t feel like dealing with them saying, “O, come on, what are you doing? Do we have to wait for you?” [Laughs] I’d spent all day long doing everything that David wanted to do, and after that, everything Mingus wanted to do, and they didn’t want to wait a few minutes while I took a few shots. But I’m glad I asserted myself, because the images are still alive and treasured after thirty years.

Talbert: Your career started in the 1970s, and then you had a show in 2000, twenty-five years later, in LA [at Watts Towers Arts Center] that was written up in the LA Times. Many other things happened in between, and recently there’s been a new appreciation—a resurgence of interest in your work. You’ve had a retrospective at Steven Kasher Gallery in New York, and your work appeared in 2017 in Soul of a Nation at Tate Modern and We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 at the Brooklyn Museum. You’ve also shown at Frieze and Frieze Masters; and institutions including the Whitney, Getty, and National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, as well as MoMA, have all acquired your work—and that’s just in the last few years. In the quieter times of your career, how did you keep going when your work wasn’t getting as much attention as it deserved? Were you still shooting? When did you start painting?

Smith: Going through a divorce in the early ’90s, I moved to LA. The first time I started painting, as opposed to color tinting, was on Easter 2000. Mingus was away at a basketball tournament, and I didn’t feel like going anywhere and socializing, so I had quiet time. But almost everything that I’ve ever created came from my quiet time. Even when I was married and on the road with David, I would leave the family in bed and I would go out and shoot, and by the time I returned, they were getting up.

Talbert: When it’s quiet.

Smith: Quiet. No distractions—versus distractions, like I’m painting and all of a sudden someone says, “Will you fix me a sandwich, or spaghetti?” just when I was in the middle of my thought. [Laughs]

Talbert: When you look back at your career thus far, what were the highlights? Do you have any regrets?

Smith: Well, of course, being in MoMA was the highlight, and being in We Wanted a Revolution. I was really happy to be included. Those were the two main highlights. But actually, it’s being acknowledged for my work.

In 1981, I was in a show called Artists Who Do Other Art Forms at Linda Goode Bryant’s gallery, Just Above Midtown (JAM). I wasn’t really part of that scene, but I remember when Linda called and asked me to be in the show, I just said, “Sure.” She had heard I was a dancer too. In front of my installation, I danced and David played the saxophone, and my photographs were projected onto the wall, flashing in the background. Someone videotaped it, but I never received a copy. Someone somewhere has that tape . . . Because I was dancing, I wasn’t able to photograph, but I recently found a slide from that night. For the most part back then, I was shooting without getting any compensation or acknowledgment. So I was lucky to be a part of JAM, along with other artists, like David Hammons, Dawoud Bey, and Howardena Pindell.

Talbert: It goes back to your belief about doing the work. Being in that show was just part of doing the work.

Smith: And I was in complete support of Linda! A Black woman? Starting her own gallery? Linda Bryant had a dream.

Talbert: You have about fifty to sixty photos that make up your series August Moon for August Wilson (1991), and you’ve talked about turning them into a book similar to The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), which had photographs by Roy DeCarava and text by Langston Hughes.

I just love that book. It was my inspiration. After I saw August Wilson’s play Two Trains Running (1990), I wanted to go to Pittsburgh and shoot. His characters were characters I knew and loved. In Pittsburgh, the people were light to me. They were light within all the violence and all of the pain. They were folkloric.

Talbert: Some of your photos have appeared on album covers.

Smith: I did some album covers for David, but also for the World Saxophone Quartet (WSQ). So along with the album covers, I took these beautiful photographs of the quartet and I had them framed—and framing was expensive. They were having a meeting and we took the framed photos to the meeting, and what did the guys do? They said to David, “You just want to promote your wife!” They didn’t want to look at the photos! Male egos! I hurried out of there and I was so furious, I threw them down on the sidewalk, breaking the glass.

Talbert: But the photos did make it onto the album, right?

Smith: Yes, but guess what? A year later, those same guys asked me, “Do you have a free PR photo we can use?” And for about ten years after that, those photos were still being used for promotion, including in DownBeat magazine.

Arthur Jafa first discovered my work on the album covers of David and WSQ. We’d never met, but he called me after he finished the cinematography for the film Daughters of the Dust (1991) and told me how much he loved my work and was inspired by my images. We didn’t meet face to face until years later.

All photographs courtesy the artist

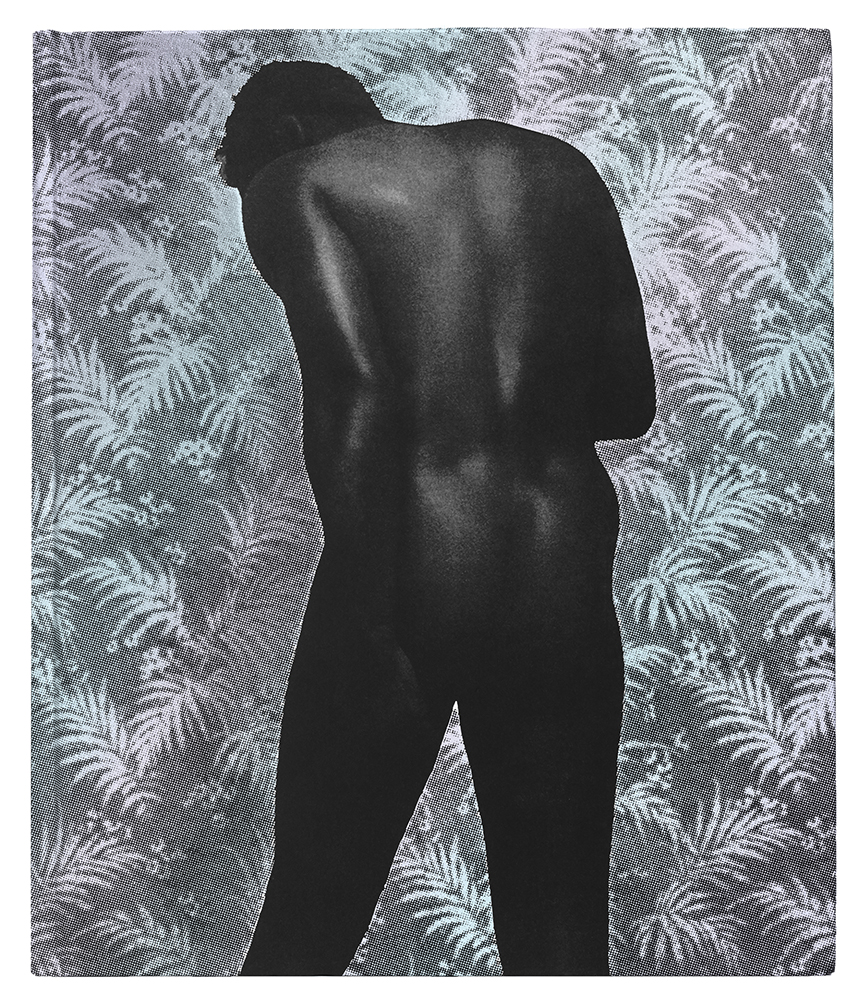

Talbert: Your Transcendence series (2006) was shot in Columbus, and many of the photographs have been enhanced with paint. Some have a little paint added to them, others are awash in paint. They are exquisite.

Smith: The title Transcendence comes from the music of Alice Coltrane. Transcendence was part of her spiritual journey, her musical journey, her life journey with her husband, John Coltrane. When I was growing up in Columbus, there was Jim Crow, the Ku Klux Klan, violence, and all kinds of injustices. Columbus, Ohio, could be very racist.

Talbert: So the Transcendence series is about elevating contemporary Columbus?

Smith: Elevating my experience of Columbus, because when I left Columbus to go to college, I said I would never go back. I didn’t have any help choosing a college. I just figured things out on my own. My high-school counselor kept saying to me, “Why do you want to go to college? You’re only going to be a domestic and scrub floors.” So I had to deal with that type of attitude. He didn’t understand. No one really understood. I used to be attacked by a little white girl almost every day on my way to school when I was in first grade. I had to pass by her house, and every day she called me the N-word. It was because the neighborhood that had been all white was becoming Black. So the Transcendence series was a way of transcending all of that, creating art out of that pain.

Talbert: Transcendence seems to be one of your long-running themes, maybe even your philosophy about photography.

Smith: I think photography is mystical, spiritual, magical. It really is. That’s what it is.

This interview originally appeared in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020).