Essays

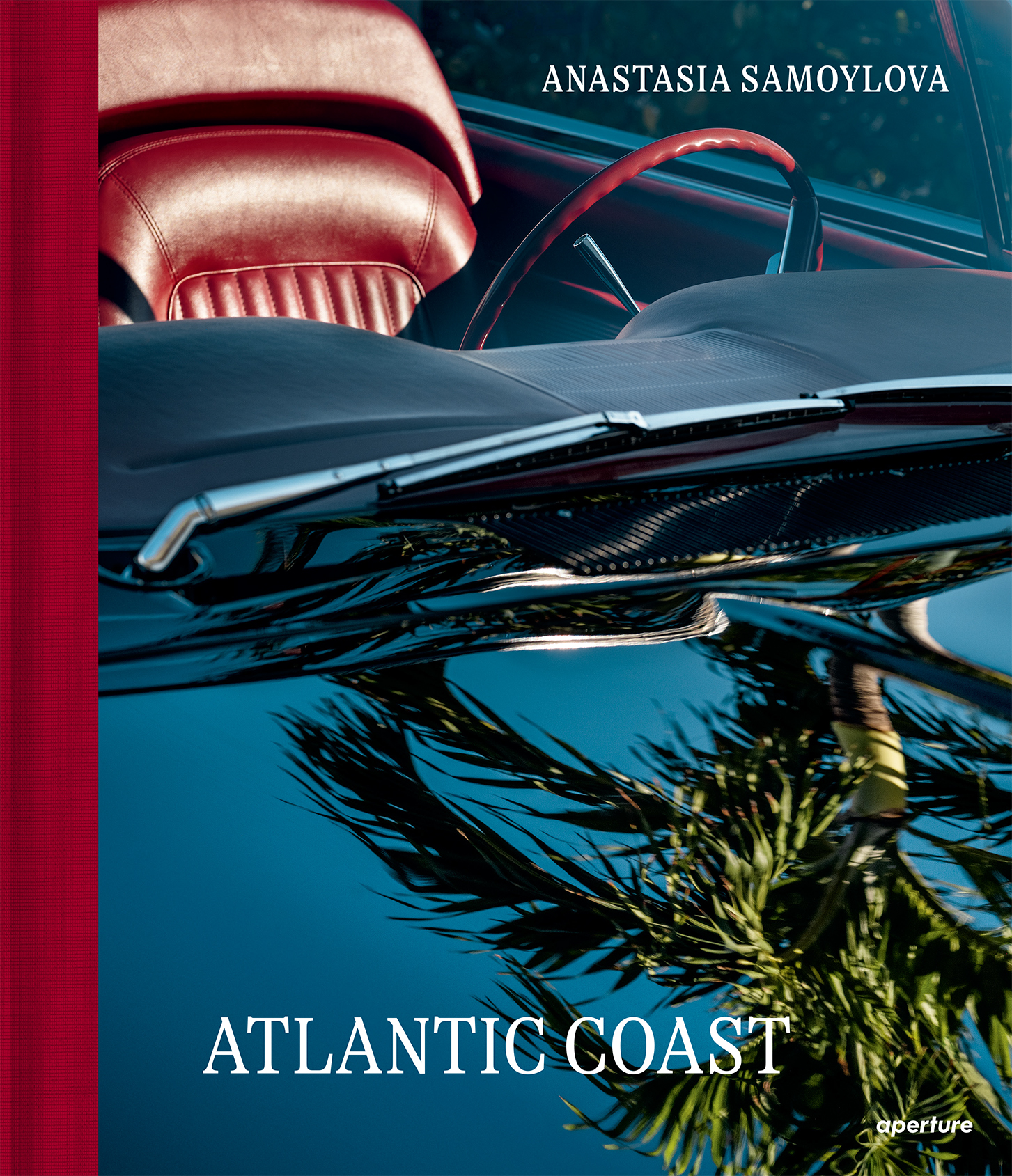

Anastasia Samoylova Maps a Decaying American Dream

In 2023, the photographer began a journey from Florida to Maine along the Atlantic Coast, tracing the ruins and resilience of postindustrial life on US Route 1.

How to see America—in all its vast, messy contradictions, in a way that makes an argument, even a partial one—for what it is without smoothing over the simultaneous glory and pain that have structured the nation since its founding, not silencing any part of it, not allowing ourselves to maintain our comforting, myopic, partial views of our little slice of a much larger American pie?

If you were Berenice Abbott, say, or Robert Frank or Stephen Shore, you might go on a road trip—cut through the country, using roads that crisscross the land, sometimes in ways that replicate how Native Americans and early European colonizers traversed it—as a way of mapping the nearly unmappable: not just the space but the place, the sum of geography and politics and culture and economy and power and history that shapes it. For Abbott, it was a trip down US Route 1 from Fort Kent, Maine, to Key West, Florida, and back again, in 1954. Abbott made it with the hope of recording what she suspected would be imminently lost: namely, the small-town ways of life, and even the culture of larger cities, in the face of the expansion of the Interstate Highway System. For Frank, it was a tour across the country in 1955 and 1956 with the aim of recording every stratum in American society, where his outsider view—he was a Swiss immigrant—gave his pictures an air of critique, a refusal of romanticism and nostalgia. They registered disapproval, even, of the ways in which the harrowing class and racial disparities of American society were—and still are—papered over by the shiny optimism of the new that defines American consumer culture. And for Shore, it was a 1972 trip along Route 66 that turned into a photographic diary—“every meal I ate, every person I met, every bed I slept in, every toilet I used, every town I drove to”—shot not in black and white, but in color.

Like Frank, Anastasia Samoylova has an immigrant’s view of the United States, one conditioned by a life outside it. But in 2023, when she began roughly retracing Abbott’s route from the tip of Florida, her adopted state, to Maine, her status as an “outsider” documenting aspects of American life was conditioned, too, by the photographic history of the American road trip. It functioned as both an inspiration and a foil, the way, say, Walker Evans’s photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) functioned for Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958). To get in the car with a camera in hand now, not quite two hundred years since the invention of photography, is an act of looking outward, yet it’s also looking inward to the very terms of the medium and its past.

Samoylova notices these relics of the past without falling into the trap of nostalgia.

This self-referentiality shows up in the way the past bumps up against the present in Atlantic Coast. It is a comment on the way this country has never truly reckoned with the original sins of its founding—slavery and genocide above all—so that the past appears, like the return of the repressed, in many of Samoylova’s images. But it is also an engagement with photography’s development over time. One could point to Historic Reenactor, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for example—a woman whose outfit looks to be out of the 1940s, pin curls and headscarf, white collar and jolly printed apron—behind the counter of an old-fashioned sweet shop. Samoylova doesn’t underline the artificiality of the scene or give us any means to recognize it as a fiction; there is no obvious “tell” to let us know that this isn’t a historical photograph, other than the title and the technical qualities of the photograph and print themselves. Samoylova takes up the documentary approach of someone like Abbott or Frank or even Evans; she takes up the challenge of the road trip with all its historical freight, but even more, she allows her subject to occupy a time closer to those forebears than her own.

Automobiles play a large role in this confusion of timelines. The massive, grumpy hog in Hog, Old Lyme, Connecticut, stands in the back of an old-timey pickup truck. A vintage blue Oldsmobile sedan looks out from a shed like garage in Brunswick, Georgia. A rusted-out jalopy is parked next to equally antiquated gas pumps at an abandoned Esso station near Lubec, Maine. (The levels of obsolescence here are myriad—the place is falling apart, and the company itself, long ago absorbed into ExxonMobil, no longer exists in the US.) Palm trees are reflected in the hood of a lovingly maintained Thunderbird in Palm Beach. An out-of-date hearse sits forlorn, “For Sale by Owner” sign in its windshield, near Orient, Maine. In East Harlem, Samoylova picks out two old cars parked nose to tail—Cutlasses, I think—whose colors (cream and copper brown) echo the depressing, small-windowed, low-income housing aesthetics of the brick apartment blocks behind them. Even in her photograph of a diner in Raleigh, North Carolina, the view is dominated by the pictures on the wall rather than the work going on in the kitchen, which is seen through a framed cutout on the lower left. Of those pictures, the most prominent is a painting of a man posing proudly by his 1950s-era blue truck.

Blue Corvette

1800.00

$1,800.00Add to cart

It’s not that there weren’t lots of late-model cars to photograph—Samoylova’s eye was caught by them, too, but in fewer numbers. Rather, she seems to have been interested not in the relentless sameness of American consumer culture that she was inevitably confronted with during her travels (a feature that Ed Ruscha pushed to the extreme in his 1963 photobook Twentysix Gasoline Stations) but on the singular detail. She notices these relics of the past without falling into the trap of nostalgia. Yes, the repetition of old cars, old churches, old movie theaters, old houses throws us back to the 1950s. This is more or less the heyday of what we now imagine as Americana. But in Samoylova’s hands Americana is portrayed not so much as a golden age but as a ruin.

Ruination is not simply the entropic erosion of the past but a condition of life in the present, according to the photographs in Atlantic Coast. Witness the collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, a shocking failure of infrastructure that caused havoc for weeks in 2024 near the I-95 corridor (a successor to US Route 1), and among the most heavily trafficked interstates in the country. Or a wire clothes hanger that has been twisted to read “Affordable Healthcare,” dangling from a metal pole against a twilit sky in Miami. Or denim jeans drying on a fence in Fort Lauderdale, in a yard that has been flooded knee-high due to climate change. Or a leaflet taped to a pole near a marina in Bar Harbor, Maine, that reads: “LOOKING FOR WORK.” “Healthy, Hard Worker, Sober,” it continues. All of these are records of the insupportability of daily existence in the now.

We are living in a state of collapse. We also live among ghosts. We are haunted. A wall in West Palm Beach shows the barely visible remnants of decals that have been removed: “Sell New & Used Guns Ammo.” In Charleston, we see the removal of a statue of John C. Calhoun, vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832, slaveholder, and ardent defender of the institution of slavery. A church spire in Savannah, viewed through an elevator window, is blurred, made inchoate, like an imperfect memory, by layers of dirt and peeling, weathered glass coating. If these are manifestations of history at large welling up in the present, there are moments when art history does, too, most strikingly in House Flag, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where a figure is partially obscured by an American flag and backlit, so that we see only their silhouette. The image is a subtle echo of one of the most famous images from Frank’s Americans in which two women watch an unseen parade from adjacent apartment windows, one of their faces obscured by a large flag floating across the facade.

I’ve emphasized the bleakness that Atlantic Coast portrays, and perhaps that is because of my own experience of this country as a person of color. I am uneasy, even low-key terrified, when I look at the stained glass window in a church in Pooler, Georgia. Three bomber planes roar above an angry—perhaps even vengeful—Jesus; a coat of arms for the 448th Bomb Group sits at the top of the composition, in tribute to its actions during World War II. Below the armorial, their motto reads “Destroy.” I feel the same sense of unease when I see a close-up of a woman’s hand resting on her woven American flag shawl. Her wrist is adorned with friendship bead bracelets, and her index finger sports a ring in the form of a rhinestone-encrusted gun. I feel it again when I meet the steely, suspicious gaze of the Civil War reenactor whom Samoylova encountered in Fort Knox, in Prospect, Maine. This is the America that I fear—the one that cannot let go of the idealization of war, whether wars of the past or an imagined war of enemies within. In the face of these encounters, unlike Frank’s, Samoylova’s point of view is not explicitly critical or judgmental—but ironically, this makes her pictures all the more troubling. While Frank took stealthy snapshots of people going about their business (showing us, in effect, what they were doing when they thought they weren’t being observed), Samoylova photographs people who are active participants in their self-presentation. They want to be seen this way.

All photographs © the artist

But there is vividness too—reminders that life persists in the United States, that joy persists, that pleasure persists. An extravagantly flowering wisteria tree growing from inside an abandoned blue brick building in Baltimore, reaching out from a broken window. A young man, shirtless, soaking up the sun in front of the White House, and in another image, an older woman in a Barbie-pink Western getup—suede cowboy hat, satin shirt fringed with beads and sequins—doing the same in Homestead, Florida. And then there are two women, both Black, one in Darien, Georgia, and the other in Miami. The woman from Georgia looks up to the sky, eyes fringed by press-on lashes and a mouth in a wide smile as she shows off her utterly fabulous sweater with an appliquéd design of a nineteenth-century Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcut print. We see the Florida woman only from behind, as she poses in a sexy contrapposto, wearing a shimmering, formfitting dress cinched at the waist by a wide belt. The color here is sublime, equal parts heaven and hell: the crimson of her garment, the indigo of the shadows framing and defining her figure, the orangey yellows and teals and greens seen further afield, and over her shoulder, the deep darkness of silhouettes of fellow partiers; her Afro is like a halo. If so many of the images in Atlantic Coast make me painfully aware of the America I live in, these crucial few offer a picture of what America could be—a place that celebrates uniqueness, individuality, and the pursuit of happiness.

This essay originally appeared in Anastasia Samoylova: Atlantic Coast (Aperture, 2025).