Essays

Eikoh Hosoe’s Mythic Worlds

In his collaborations with influential literary figures and performers, Hosoe created surreal scenes that invoke the fantastic.

It is said that the kamaitachi spirit resembles a weasel, rides on a whirlwind, flies through the air, and moves so incredibly fast that before you know it it’s already gone. With strong and sharp claws, the invisible beast attacks suddenly and sucks blood from its victim’s wounds.

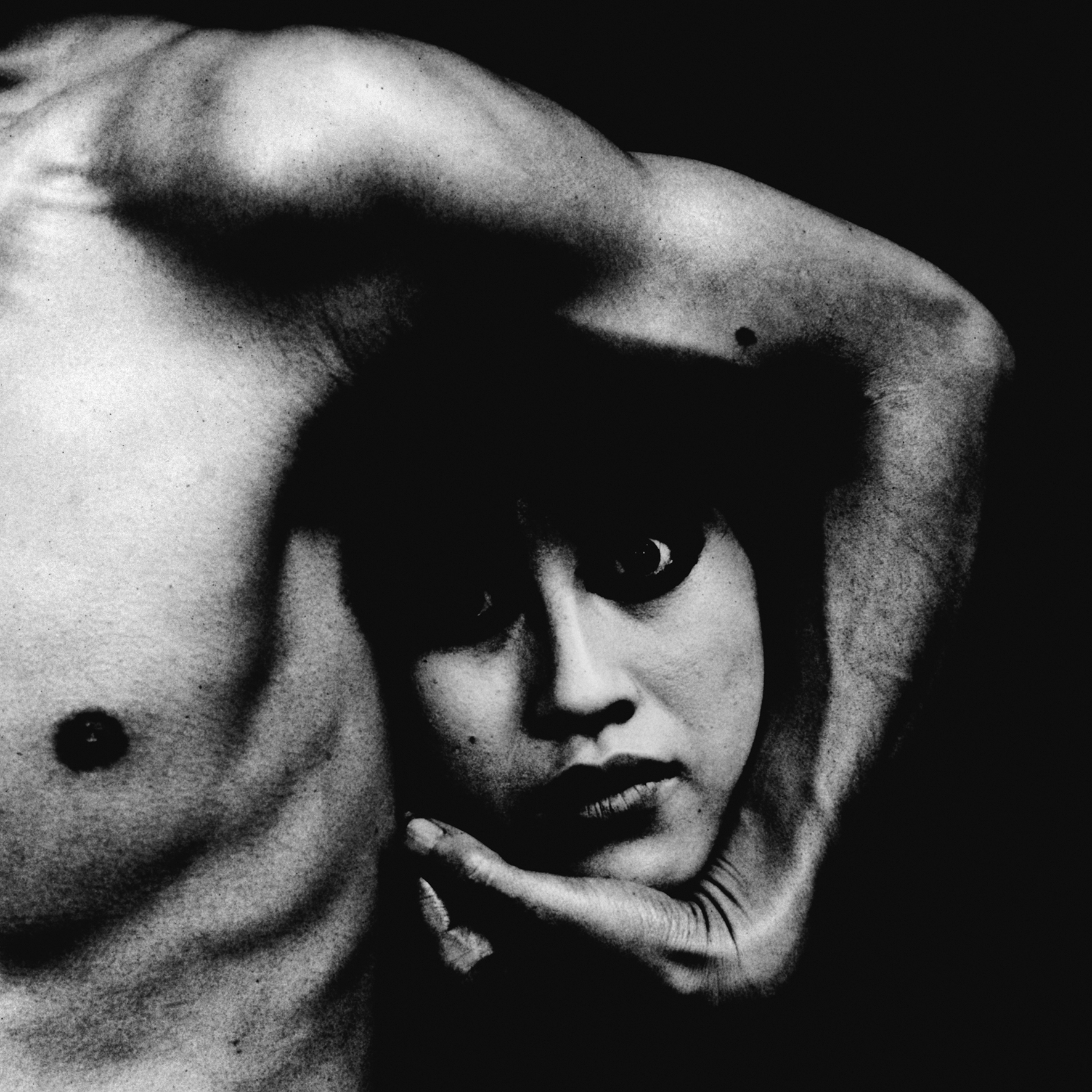

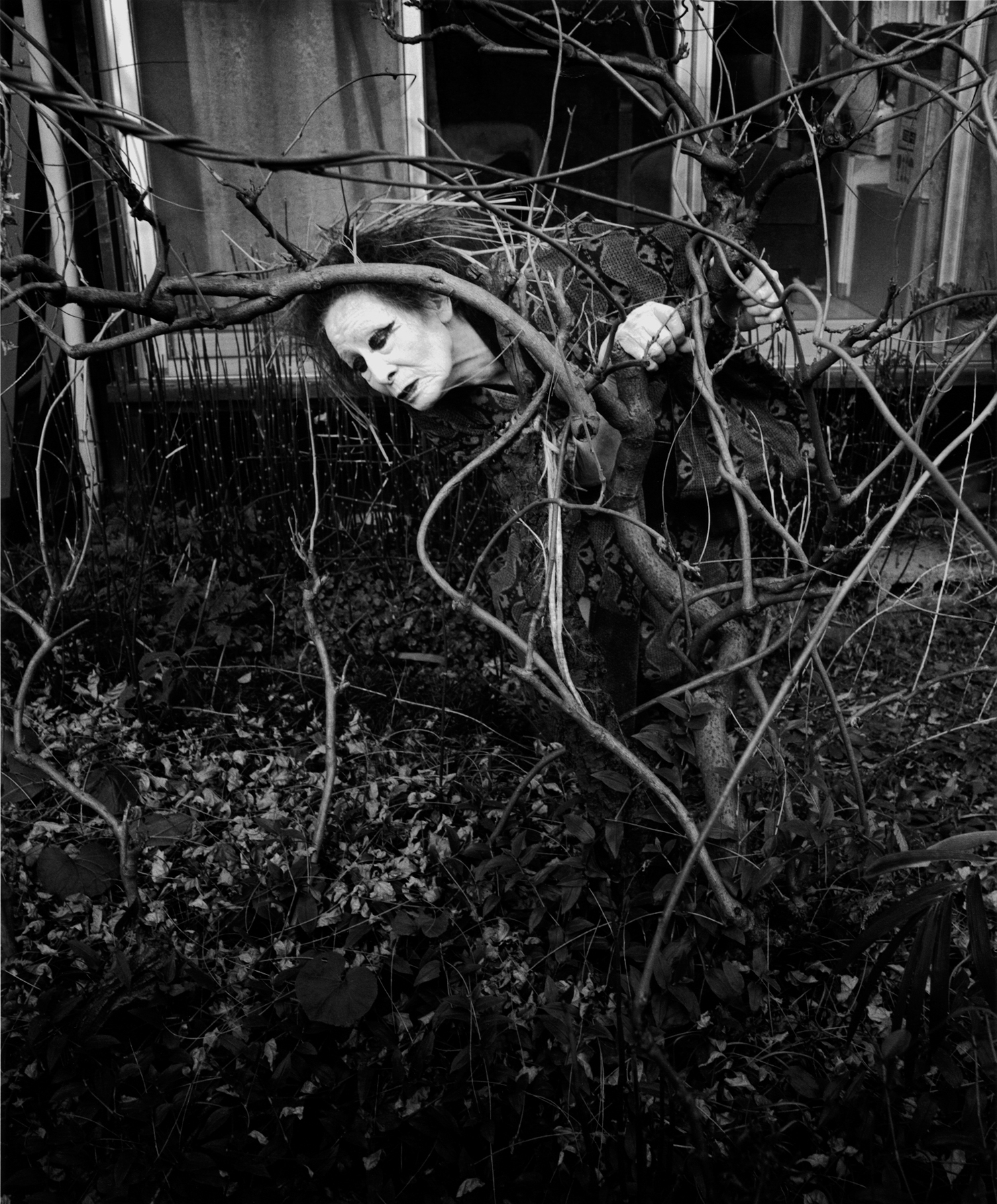

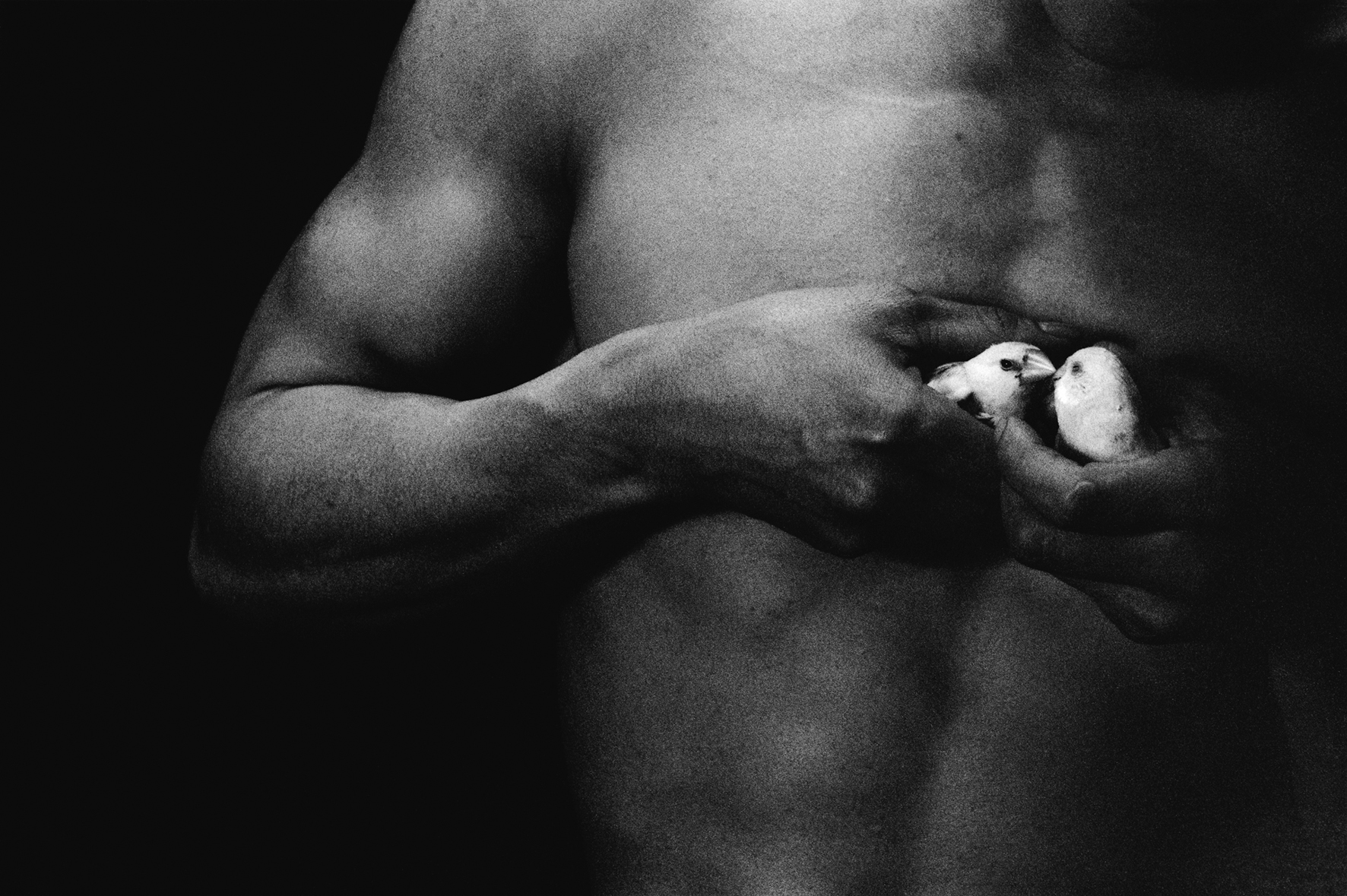

Such a kamaitachi, half-naked and with its clothing blown up by the wind, jumps high in front of a group of curious farm children. Darkly surreal, a female head appears under a male arm and stares at the viewer, her eyes wide open. An androgynous figure runs across Tokyo. A young woman sits pensively between portrait paintings and striking busts with crying faces. Hauntingly poetic and depicted in high-contrast, these scenes tell of human physicality, sexuality, and a wide array of emotions. The images, by the legendary Japanese photographer and filmmaker Eikoh Hosoe, are expressive, subjective, and mythic; they whisper, speak, and shout fantastical stories that engrave themselves in the viewer’s mind.

Brought up in a Shinto shrine where his father was a priest, Hosoe, who was born in 1933, came to photography at a young age. He borrowed a camera that belonged to his father, who supplemented his income during World War II by taking photographs at festivals and graduation ceremonies. In 1951, as a teenager, Hosoe won the inaugural Fuji Photo Contest and first gained widespread attention in the photography world with his 1960 solo show Man and Woman, at the Konishiroku Photo Gallery, featuring stylized nude compositions that reflect his career-long interest in the human body. Hosoe’s fascination with the body’s forms, movements, and eroticism is evident also in what was to become his best-known series: Ordeal by Roses (1961). The theatrical photographs featuring the writer, actor, and ultranationalist Yukio Mishima, a tireless promoter of his celebrity image who would commit ritualistic suicide through seppuku disembowelment a few years later, convey a sense of dark eroticism. “The series made me famous, and I started to work with Light Gallery in New York,” Hosoe told me recently. Selling prints overseas enabled him “to live a good life and get married.” And, he recalls, “Mishima came to my wedding and gave a rather ironic speech.”

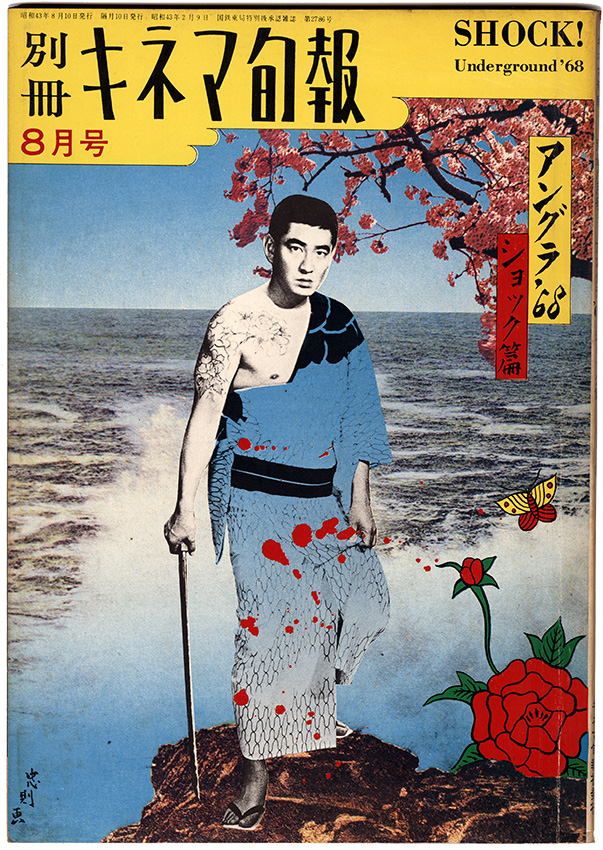

For his equally striking series Kamaitachi (1965–68), Hosoe collaborated with Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the founders of the experimental dance form butoh. The work is linked to the photographer’s childhood memories of the war, when he was evacuated to the rural Tōhoku region. Hijikata, who grew up there, embodies the kamaitachi spirit of folklore said to haunt the rice fields. The dynamic scenes show the dancer running in the fields, dramatically jumping, hiding, or “stealing” a local farmer’s baby, and they also often mirror Hosoe’s own physical involvement, taking photographs while running or from unusual vantage points. Even today, elderly people in the village remember the photoshoots.

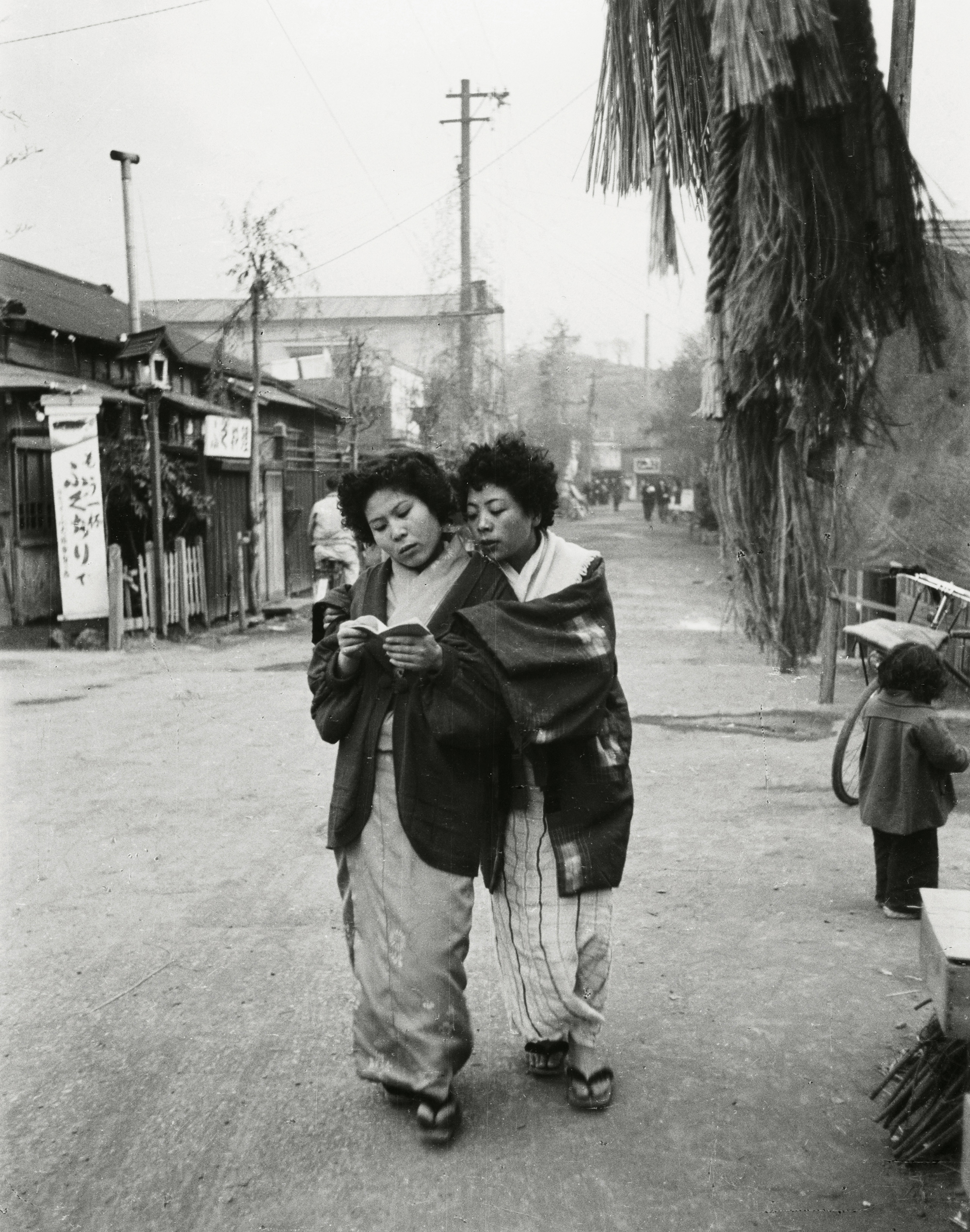

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Soon after, Hosoe began to work with Ohno Kazuo, the other founding figure of butoh; this collaboration was to last for more than forty years. Another highlight in Hosoe’s oeuvre is the series Simmon: A Private Landscape (1971), which features the artist and actor known as Simmon Yotsuya—a stage name inspired by the artist’s love for Nina Simone’s music and the Yotsuya district of Tokyo. The beautifully made-up, effeminate actor was a participant in Juro Kara’s avant-garde Situation Theatre troupe (Jōkyō Gekijō). Hosoe photographed Simmon Yotsuya in different areas of Tokyo, including around Kannon Temple in Asakusa. His energetic poses and facial expressions are juxtaposed with the urban landscape, blurring the lines between the real city and passersby, on the one hand, and the performative and photographic narrative on the other. This results in an expressive aesthetic that links the performer’s inner “private” side with the outer “landscape.” In contrast to Kamaitachi, Hosoe has described the series as a recollection of his adolescence when he had returned to Tokyo: “I have created works based on special encounters with photographic subjects. At that time, I had met Simmon Yotsuya—through him, the adolescent scenery of Tokyo awakened from my memories and was turned into a work of art.”

Eikoh Hosoe, A Private Landscape #13, 1971

Hosoe communicates memories and personal realities, challenging conventional notions of photography. In 1950s and 1960s Japan, his work embodied the hunger for a subjective and experimental form of photography in opposition to the then dominant trend of social realism. The photographers’ group Vivo, named after the Esperanto word for “life” and cofounded by Hosoe in 1959, is an early manifestation of this hunger. Like Hosoe, its five other members, Kikuji Kawada, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, Akira Tanno, and Shomei Tomatsu, had participated in a group exhibition titled Jūnin no me (Eyes of Ten) at Konishiroku Photo Gallery two years earlier, organized by the photography critic Tatsuo Fukushima. The Vivo artists shared an office, a manager, and a darkroom in East Ginza, Tokyo. Despite existing for only two years, this office became the epicenter of a new subjective style of photography, whose protagonists were soon referred to as the Image Generation and became highly influential in the history of Japanese photography. As the critic Kotaro Iizawa once wrote, the Vivo members “gave the image its independence.”

Dramatic and dreamlike, Hosoe’s imagery remains radical, powerful, and moving—it deserves to be discovered by a wider audience.

Whether presented individually or as a series, in exhibitions or photobooks (often designed by key figures of Japanese graphic design, such as Kohei Sugiura and Tadanori Yokoo), Hosoe’s photographs grab viewers and lead them into a cinematic world. None of the series have a beginning, ending, or story line; however, most of them convey a strong narrative quality. But whose stories do they tell? They are born out of collaborations, while also recording a specific time and place. The narratives are based on Hosoe’s artistic choices in terms of photographic angle, perspective, light, shadow, background, and printing techniques in the darkroom just as much as they come into existence through the facial expressions, spontaneous gestures, and movements of the photographic subjects. Hosoe creates an inspiring atmosphere in which the performers and the photographer engage in a fantastical Ping-Pong match, passing ideas back and forth to each other.

In a recent monograph titled Eikoh Hosoe: Pioneering Post-1945 Japanese Photography, edited by Yasufumi Nakamori, the curator Christina Yang proposes viewing Hosoe’s expansive practice as “exquisite world-making”—I suggest attributing this act of “world-making” to Hosoe as well as to the people in front of his lens, situating both on a par with each other. It is no coincidence that the subjects of Hosoe’s best-known photographs are strong characters who enjoy working with their bodies and faces, be they dancers, actors, or public figures such as Mishima, who transformed his physique through bodybuilding. Hosoe is aware of the photographic subjects’ power during the creative process; unlike his peers, he has credited Hijikata, Mishima, Simmon Yotsuya, and others, acknowledging them as equal collaborators. With many of them, he developed a friendship. When I asked Hosoe a few years ago what he likes best about photography, he pointed first to his subjects, responding that “the most interesting and attractive aspect of photography is the simple joy of the people who are photographed. I have always liked human relationships.” Storytelling in Hosoe’s photography is based on an indescribable fantasy world that exists between the photographer and photographic subject(s); a unique moment of space, time, and feeling is captured on camera, during the vivid exchange of ideas.

All photographs © the artist and courtesy Akio Nagasawa Gallery

This March, Hosoe will be ninety years old. With his distinct visual language, pioneering collaborative approach, and relentless activity promoting photography in Japan—including through education and copyright protections—he has been one of the country’s most influential photographers since the postwar era. Hosoe has inspired his peers as well as younger generations of artists. Kikuji Kawada, a legendary photographer himself, who is best known for his experimental photobook Chizu (The Map, 1965), described Hosoe as someone who “searched for a new world of thought based on the eye,” creating “dramatic evidence and unforeseen stories within overwhelmingly photogenic and poetic frames.” It is telling that, having aspired to be a diplomat and also having won Tokyo’s very first English speech contest as a child, Hosoe chose the Japanese character ei for his pen name, Eikoh, which is also used in the term eigo, “English,” suggesting internationality. According to Kawada, both the Vivo office and what is now the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum would probably not have been founded without Hosoe. Daido Moriyama, who at the beginning of his own photographic career in Tokyo assisted Hosoe, argues that before Hosoe, the Japanese photography world was dominated by a type of photography that had “a strong sense of documentary and was strictly not staged. Hosoe confronted this, creating theatrical, staged photographs based on collaborations with the photographic subjects. It was a major achievement.”

With his openness, beginning in the late 1950s, to viewing photography as a form of creative collaboration, Hosoe was well ahead of his time. After early attention in the United States and Europe, however, his work has not been exhibited on a large scale outside of Japan. Dramatic and dreamlike, Hosoe’s imagery remains radical, powerful, and moving—it deserves to be discovered by a wider audience internationally, including all current and future photography lovers.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”