Telling Time in Bamako

A report from the tenth edition of Rencontres de Bamako, West Africa’s venerable photography festival.

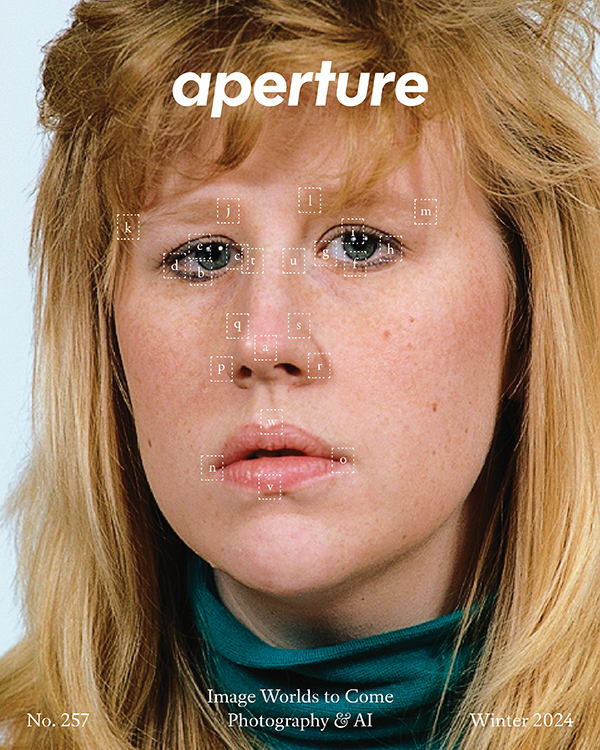

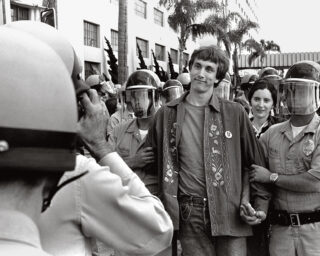

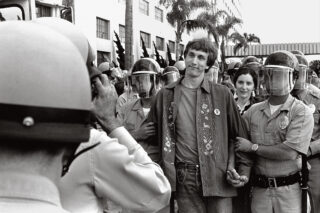

Rencontres de Bamako, Mali, 2015. Photograph by Joseph Gergel

How does one tell time? Telling time can be an action that points to a precise moment, a split second of a minute of an hour of a day. It can also refer to a grammatical tense, signaling now, before, or the future. Time is central to photography, inherently capturing the tension between the past and the present. And in relation to Africa, “telling time” might question the continent’s dynamic history and an imagining of what is to come in an increasingly globalized age.

Installation view of Nassim Rouchiche’s series Ça va waka (2015) at Rencontres de Bamako, 2015. Photograph by Joseph Gergel

In the tenth edition of Rencontres de Bamako (Bamako Encounters), the biannual festival of photography in Bamako, Mali, the thematic spectrum of “telling time” calls to the forefront photography’s symbiotic relationship with temporality and opens dialogues that transcend eras, geographies, and philosophical plateaus. Featuring thirty-eight artists working in photography and video, and spanning the African continent and the diaspora, the biennale explores the social, political, and ideological landscape of Africa today. Directed by Bisi Silva, a Nigerian independent curator and founder of the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, together with associate curators Antawan I. Byrd and Yves Chatap, the biennale presents a diverse selection of lens-based artists that mixed documentary, performative, and conceptual practices. As Silva explained, Telling Time “allows us to chart a new beginning that takes cognizance of today’s realities.”

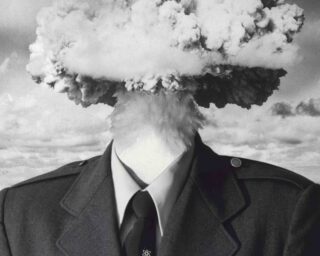

Georges Senga, from the series Une vie après la mort, 2012 © and courtesy the artist

In fact, the timing of the biennale speaks to Mali’s continued struggles in the present. In the wake of the festival’s three-year sabbatical and the cancelation of the 2013 edition due to political conflicts, this edition acted as a vehicle for interrogation and reconciliation at a pressing and urgent moment. No one could have imagined exactly how urgent this moment actually was. Only three weeks after the biennale’s official opening, Islamic extremists attacked one of Bamako’s luxury hotels, killing twenty people in a hostage siege that lasted over seven hours. Following the attacks in Paris and Beirut a week prior, such a catastrophe is not one that pertains to Mali alone but that extends as a global crisis.

This edition of the festival also marked its twenty-year presence as a leading photography festival in Africa, setting a precedent for artistic innovation that has cemented the careers of some of Africa’s preeminent photographers, including Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso, and Santu Mofokeng, among others. Rencontres de Bamako is supported by Institut Français and the government of Mali, a rare arrangement given the dearth of regional state support for the arts.

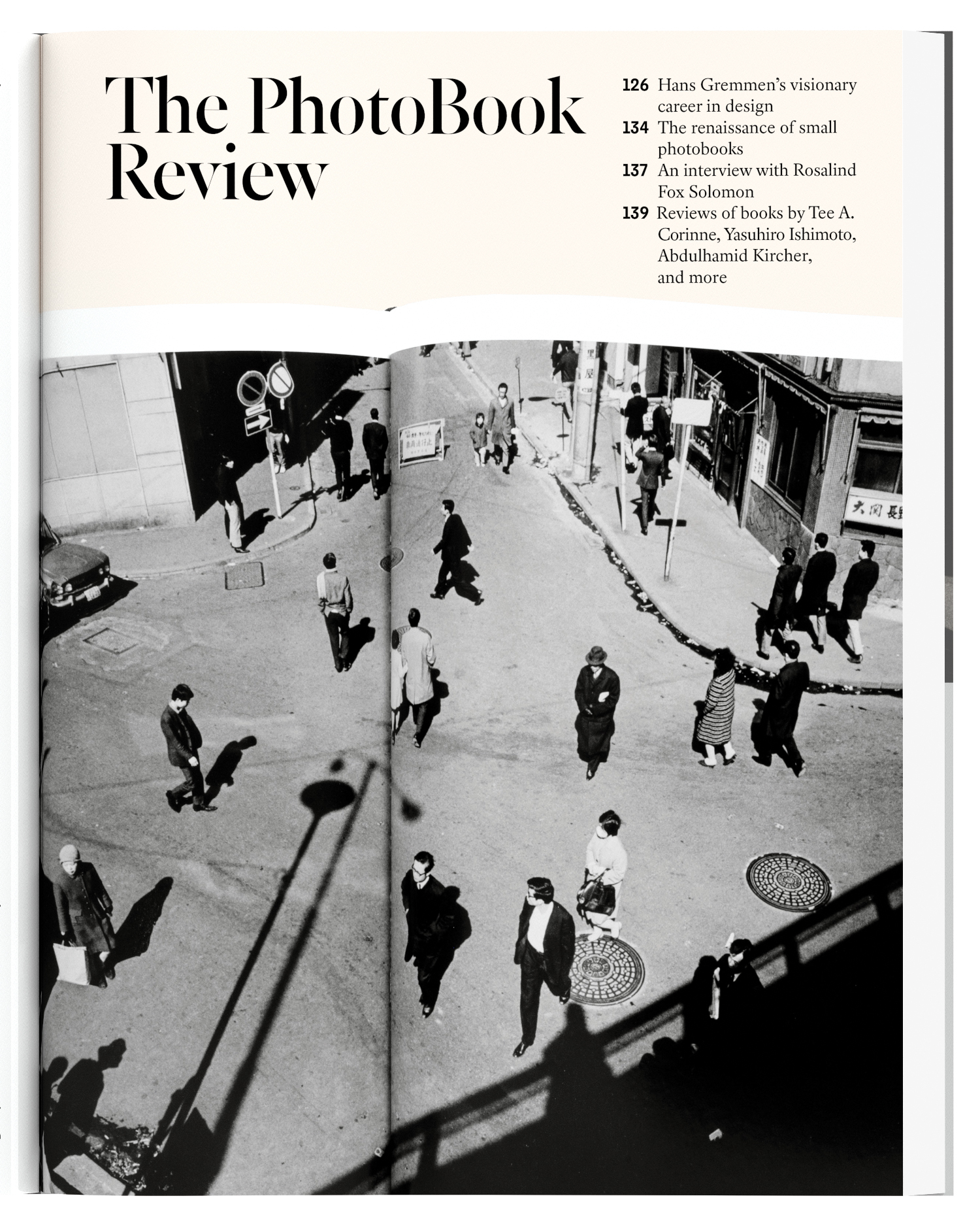

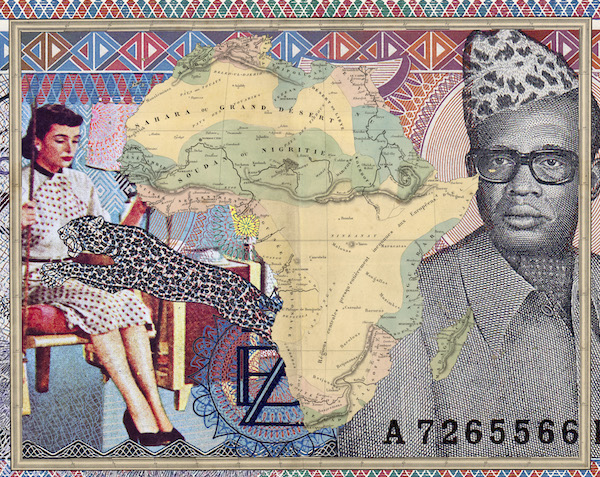

Malala Andrialavidrazana, from the series Figures, 2015 © and courtesy the artist

A concurrent thread throughout the central exhibition focused on the reinterpretation of photographic archives, with artists blending personal and cultural histories to question their relationship to the past. In her series Heir-Story, South African artist Lebohang Kganye posed amid life-size cardboard cut outs of black-and white-photographs. Reimagining episodes of her grandfather’s life in South Africa under Apartheid (based on oral recollections from her grandmother’s stories), Kganye wears her grandfather’s clothes as she interacts with the figures and objects in the images that surround her. Congolese artist Georges Senga created diptychs that juxtapose archival images of a young Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with the artist’s own photographs of an aging professor who bears a striking similarity to Lumumba. While there are visual similarities between the two representations, the newer images clash against the visible decay of the historical prints. Imagining an older Lumumba if he had not been abruptly assassinated in 1961, Senga’s series plays with photography’s ability to create fictions and form alternative narratives, circumventing the Congo’s history of political instability after independence.

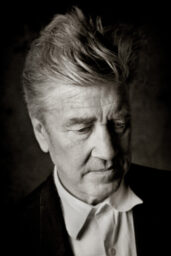

Other artists embraced the physicality of the photographic archive as a tangible object. Malian photographer Seydou Camara photographed figures sifting through the torn and faded sheaves of the Timbuktu manuscripts, which date back to the twelfth century and document African and Islamic history. Héla Ammar embroidered vernacular images of Tunisia, using both aged documents and artificially tinted contemporary images, to create a recurring design element in red silk that recalls the color of the Tunisian flag. Madagascan artist Malala Andrialavidrazana appropriated old maps, currency, and album covers to form overlapping collages, and Ibrahima Thiam created an installation of aged portraits, from the 1940s to 1960s, originating from Senegalese photo studios. These artists don’t approach the archive as a factual and static entity but rather one that is malleable and open to interpretation and reinvention.

Aboubacar Traoré, from the series Inchallah, 2015 © and courtesy the artist

Photographic performance also featured prominently in the central exhibition. Nigerian artist Uche Okpa-Iroha, who won the festival’s Seydou Keïta Prize for his series The Plantation Boy, reimagined Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 film The Godfather, by digitally inserting himself into stills, thereby questioning the dynamics of race in Western cinema. Addressing the subject of religious fanaticism in Mali, Aboubacar Traoré won the Young Francophone Photographer Prize for Inchallah, a series of staged scenes in which figures dressed in religious attire wear black circular helmets to shield their identities.

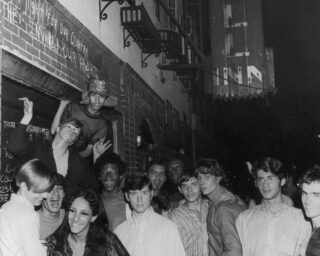

Studio Malick Sidibé, Bamako, Mali, 2015. Photograph by Joseph Gergel

As an international photography festival, Rencontres de Bamako remains rooted in the local culture and included many of its artists and art spaces. The festival launched an ambitious project that involved one hundred schools and ten thousand students through workshops and exhibition visits hosted by Malian photographers. A satellite project, Studio Mali, brought together local photographers to exhibit images in their studios. The Focus Mali section shed light on the younger generation of emerging local photographers. By inviting a diverse group of participants from throughout Africa and the diaspora, as well as garnering a significant international audience and incorporating the local community as an integral part of its programs, Rencontres de Bamako set the stage for the encounters, dialogues, and exchanges that make this festival so important.

The biennale has also created a standard for art festivals in Africa to push for a deeper reading of contemporary African photography, in particular through the accompanying catalogue, which includes an indispensible appendix of essays and an illustrated chronology reflecting upon the biennale’s tenth anniversary. As contemporary art from the continent commands a renewed focus on the global stage, Telling Time attests to the festival’s rigorous engagement with new ways of approaching photography’s complex relationship to Africa.

Rencontres de Bamako is on view through December 31, 2015.