Into the Void: Taryn Simon in Conversation with Kate Fowle

Since 2006, Taryn Simon has collected objects and documents in a black field measured to the exact dimensions of Kazimir Malevich’s painting Black Square (1915). Set to end on May 21, 3015, and created in collaboration with Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation, Simon’s newest iteration of the project, a journey into the future, is the ultimate homage—a black square of vitrified nuclear waste. Black Square XVII is now a permanent installation at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, where the ongoing series will be presented in spring 2016. With Black Square XVII, Simon explained, “I wanted to make a work not for my generation, nor my children’s generation, but for a distant future to which I have no tangible relationship.” An excerpt from “Odyssey,” the Spring 2016 issue of Aperture magazine.

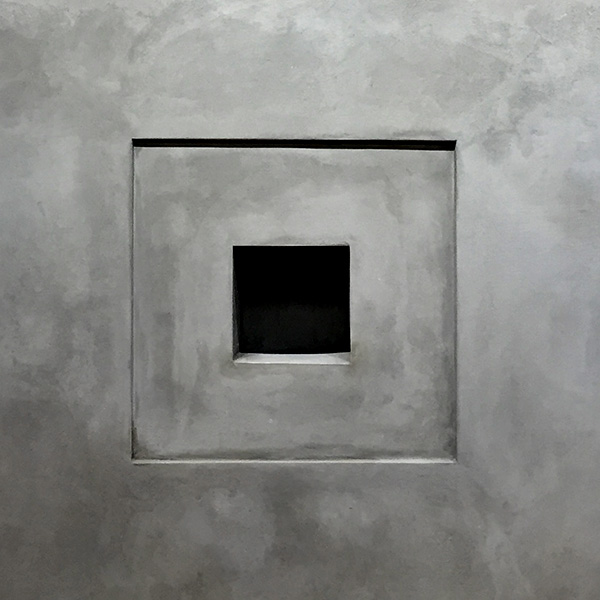

Taryn Simon, Black Square, 2006– Void for artwork. Permanent installation at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow

Kate Fowle: Black Square began in 2006 and is ongoing, making it the longest running project you have embarked upon so far. At the same time, it has never been exhibited as a series, or perhaps it’s better to say not exhibited as a complete story. Does this project enable you to structure, or think out loud, about various subjects and ideas that become important to you during your research for other series?

Taryn Simon: It was a needed liberation from the tight margins of my projects. I’ve worked for so long in very closed and serial projects—ones that take consecutive years to produce. The Black Square series has allowed me to think and work differently.

KF: It’s “action research.”

TS: I make the individual works for Black Square whenever I feel like it—not in a controlled time slot. Within the “black” I’m able to dig into the lists I collect of singular ideas. I guess the irony is that I couldn’t escape my taxonomic instinct, as I put all of these distinct subjects in the repetitive void of the black square. But, for me, it’s the messiest I’ve been.

Taryn Simon, Film still of Radon nuclear waste disposal plant, Sergiev Posad, Russia, 2015–ongoing

KF: Let’s talk about the premise of this series. Why did you choose to use Kazimir Malevich’s painting Black Square 1915 as an organizing principle? What is your own story in relation to this work?

TS: The Black Square—or the great nothing, a zero form, as Malevich described it—was the first icon without an icon in Russian painting. This average shape, size, and color was inscribed with countless political and mystical dimensions. A very simple, dull gesture became revolutionary. For years I’ve used the shape, color, and scale of Malevich’s square as background to a number of representations of man’s inventions, or man’s disruptive marks. Then the great nothing became a big something—researchers using X-rays have recently discovered that beneath the paint of the Black Square lay secret messages and earlier paintings. Ironically, the painting itself suddenly takes on overtly secretive and hidden characteristics, like many other subjects of my work. On a more personal note, Malevich’s Black Square was created during a period of Russian history that led to my family’s departure from the country.

KF: The works share a format, but their contents are all very different.

TS: The subjects of the black squares come from my imagination, things I’m reading or lists I’ve made through the years of ideas to consider for projects. There’s no real reason behind them, just things that have a certain solitude or inherent contradiction.

Taryn Simon, film still of Radon nuclear waste disposal plant, Sergiev Posad, Russia, 2015–ongoing

KF: Can you describe a couple of the works and how they came about?

TS: Black Square IV pictures “The Blaster,” an anticarjacking system installed beneath vehicles in South Africa. It’s a flamethrower activated by a driver or passenger of a car under attack. Black Square V includes a shadowed image of Henry Kissinger. Black Square XII documents The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, which purports to be the minutes of a meeting between Jewish leaders outlining their plan to control the world. Despite having been exposed as a false document, it continues to be reproduced in many languages and distributed throughout the world. Black Square XIII pictures a functional 3-D handgun printed in my studio in nine hours and forty-eight minutes, using black ABS plastic. Black Square XVIII looks at the variations in dust from different nations.

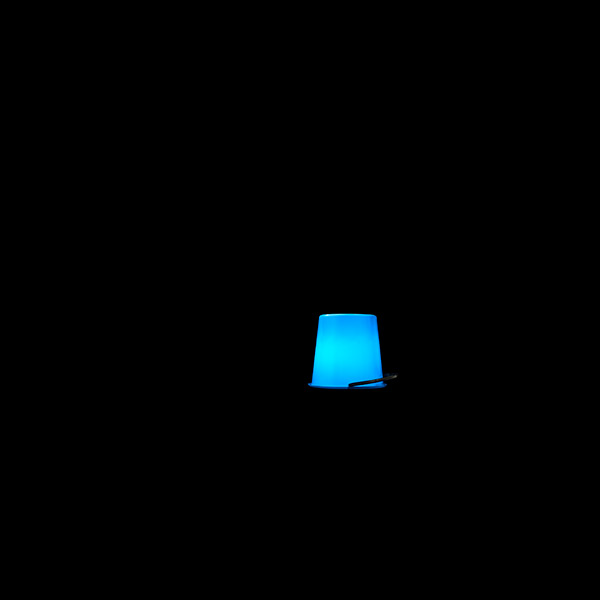

Taryn Simon, Black Square VI, from Black Square, 2006– Blue buckets were mounted atop civilian vehicles in Moscow to protest the misuse of emergency blue rotating lights by VIP businessmen, celebrities, and officials to bypass Moscow traffic. All works courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery

KF: The most recent iteration of the Black Square is a sculpture.

TS: Yes, its start was a fantasy that developed into a long-term project with Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. The goal was to construct a black square made from vitrified nuclear waste that would hold within it a letter that I had written to the future. The process of vitrification converts radioactive waste from a volatile liquid to a stable, solid mass resembling polished black glass. It is considered to be one of the safest and most effective methods for the long-term storage and neutralization of radioactive waste. At long last, in 2015, we began fabricating the black square, which will be stored in a steel container reinforced with concrete, situated within a holding chamber surrounded by clay-rich soil, and then placed at the radon nuclear waste disposal plant in Sergiev Posad, located seventy-two kilometers northeast of Moscow. It will reside at the radon facility until its radioactive properties have diminished to levels deemed safe for human exposure and exhibition—approximately one thousand years after its creation.

Kate Fowle is the chief curator at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow and Director-at-Large at independent Curators International in New York.

To continue reading the full article, buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.