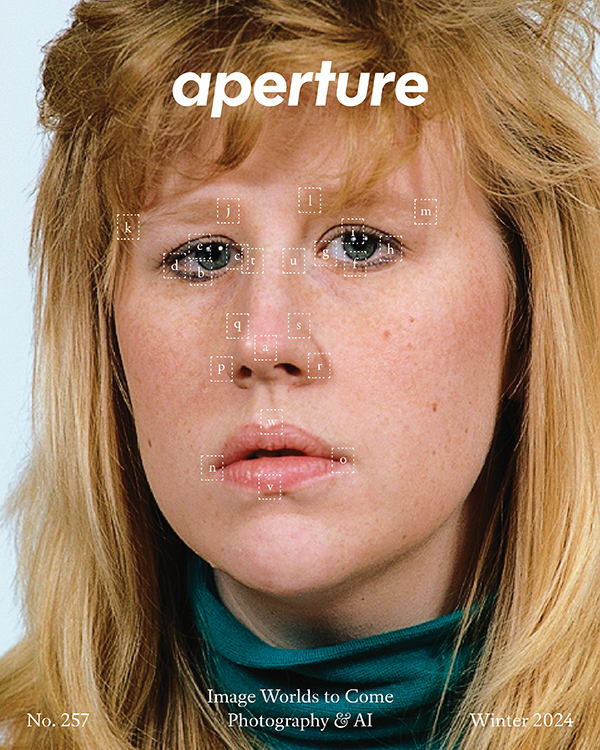

Along the Dinosaur Road: A Conversation with Yto Barrada

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show series, Ballroom, Arizona), 2014–15

A dual citizen of France and Morocco, the artist and photographer Yto Barrada examines the effects of political and economic currents, as in her first photographic series, A Life Full of Holes: The Strait Project (1998–2004), which documented the northbound flow of migration from Africa to Europe through the Strait of Gibraltar. Moroccan citizens, to whom the northern border is largely closed, are forced either to wait for the day they can legally emigrate, or “burn” their past and flee.

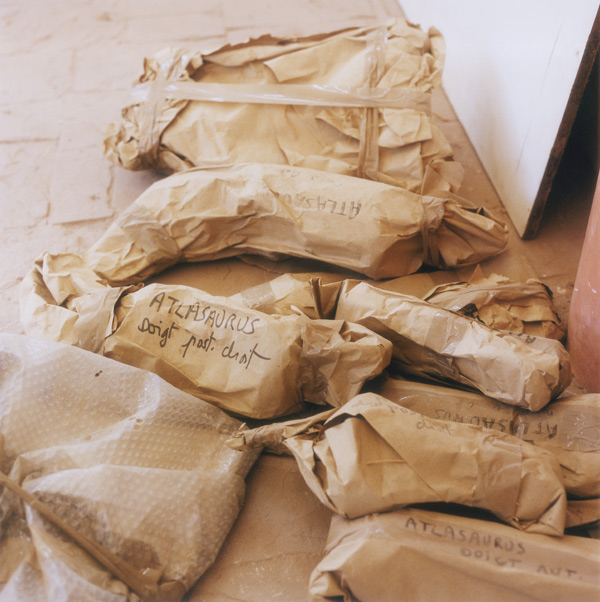

In her recent exhibition, Faux Guide, Barrada examines the exploitation of Morocco’s dinosaur trade through a myriad of mediums, including photography, film, and fabricated objects. (According to Barrada, Morocco runs a brisk trade in fake fossils.) Faux Guide also encompasses her Dinosaur Road series, which considers history, science, politics, and the construction of national identity. Previously unpublished, a selection of images from Dinosaur Road appears in “Odyssey,” the spring 2016 issue of Aperture. Introducing Barrada’s portfolio, Carmen Winant leads us along the route—from the tourist hoping to pick up a Middle Jurassic Period fossil to a mineral and fossil trade show in Tucson, Arizona. In Dinosaur Road, Winant sees Barrada’s subtle critique of this pitfall “as a cycle of discovery and myth, erosion and ruin. Some kind of full circle.” Part of Barrada’s series includes documenting Morocco’s unfinished national museums that would, if fully realized, house and protect its national paleontological treasures. Such ventures, possibly a boon to the tourist economy, might also risk degrading the very landscape the museums were built to preserve. I spoke with Barrada in December 2015 about her journey into Dinosaur Road. —Nicole Maturo

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Azilal Museum Project, Morocco), 2013–15

Nicole Maturo: What is Dinosaur Road, and how do your photographs published in Aperture fit into the larger artistic project Faux Guide?

Yto Barrada: Faux Guide (“false guide” in French) was the name of my show last year in London and Nîmes. Dinosaur Road is a group of images about the dinosaur fossil trade in Morocco. It’s also the title of a recent French-language book, La route des dinosaures, by a geologist and his wife, Michel and Jacqueline Monbaron. For years they were working on this project, and it was just published in Morocco. Their goal is to defend two museums that don’t exist yet, which are under construction to house two of Morocco’s main dinosaurs, including one of the biggest, called Atlasaurus.

My project came out of different experiments with recycling stuff collected on my road trip into collages, drawings, textiles, photographs, and books. The artistic avant-garde’s new way of looking at African ethnological artifacts and their collections was also an influence. But my current interests were about the invention of traditions and the question of authenticity. It could seem like a paradox: a tradition shouldn’t be invented; it should be something you pass on. Nationality is a nineteenth-century invention; the nation-state is a nineteenth-century invention. I’m interested in the artifacts, the histories, the stories that are linked to this construction. And the collections of a museum have often played a major role in that construction—how the museum displays the collections, what a museum chooses to put forward.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Dinosaur Road series, Dinosaur Footprints, Iouaridene, High Atlas, Morocco), 2013–15

Maturo: Is “Dinosaur Road” a real place?

Barrada: It’s not one road; it’s a whole itinerary for fossil lovers in the Geoparc M’Goun, where there are lots of sites.

In the trade, if you decide to look at the pyramid of structure, if you’re going to look at the local lumpen proletariat that work to take these fossils from the ground and prepare them; you also have the scientists, and the missions of paleontologists from around the world who can come work, since Morocco is open, making great discoveries. And, in the pyramid of structure, at the top are the dealers, the big dealers who have everything sent to them outside of the country, and deal them at international trade fairs like the Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show series, Balloon, Arizona), 2014–15

The market is changing: natural history events are popular in major auction houses, as well as with the buyers themselves, the people who are decorating their homes with national treasures. That’s one of the big trends: people are buying dinosaurs not to put in a museum, but to put in their living room.

Maturo: How chic.

Barrada: How terrible! What’s interesting with paleontology or history is the way it’s instrumentalized in the construction of a national discourse. That’s what started my interest in dinosaurs. I mean, how come we don’t use the fact that one of the biggest meat-eating dinosaur comes from Morocco? Dinosaurs should be on the tourist poster boards, you know, “Spend your vacation in Morocco with a dinosaur!” The French companies hired to do advertising still talk about “Eternal Morocco,” and show you pictures of the spice markets in Fez. “Time passed everywhere in the world except in Fez.” You could add a dinosaur to the picture, and it would make sense.

On the other hand, if the Dinosaur Road became a popular destination, mass tourism might have tragic consequences by putting pressure on fragile Berber territories. It’s a complex issue because it’s not just about the scientific community wanting to protect the paleontological sites and make the heritage visible locally with museums, it’s also about thousands of families, farmers, and their kids living in these villages nearby: they need the fossil trade to complement their small income and survive.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Salle des fêtes OCP, Khouribga) 2013–15

Maturo: What other forms has this project taken?

Barrada: The discovery of the fake fossil craft became a major part of the project. I made a film called False Start, with a grant from the Abraaj Group. This was also a project supported by the Peabody Museum at Harvard. The trip allowed me to look at the very hard work of the talented preparators and forgers who are making fake fossils. The tools they invent and build for this work are quite astonishing; there is a sequence in my film about the “beauties of the common tool.”

I was also learning a lot and interested in my own visual illiteracy and education. I didn’t know the rocks, the tools, the fossil layers, and the landscapes. Where does their scientific knowledge come from? Most of them are self-taught; they didn’t go to college, they’re shop owners who can bluff their way through—that’s where the Faux Guide title comes from. In Morocco, guys who propose their services to take you around are doing a performance.

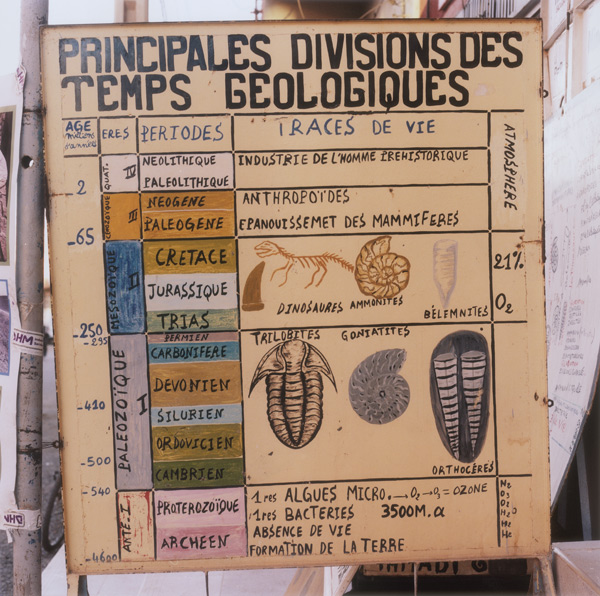

Yto Barrada, Untitled (painted educational board found on site of Azilal Museum Project, Morocco), 2013–15

In Tangier, for example, in the pre-smart-phone-GPS-world, you get off the ferry, you have twenty minutes, and you want an oriental experience in the medina, so you would find a partner to tango with and a younger guy would be your “faux guide.” He would give you, for a little bit of money, the typical experience you expect. I have a friend, an anthropologist, who worked on Tangier “faux guides” fifteen years ago.

I’m currently working on a book called A Guide to Fossils for Forgers and Foreigners, to be released this spring. It will have a little section about the “faux guides.” I’m also doing a sort of portable museum, a box, like the Duchamp box museum, where I’m going to put the treasures of Moroccan paleontology. I’m interested in the format of educational material, so it has to be transportable.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (painted educational board found on site of Azilal Museum Project, Morocco), 2013–15

Maturo: You have an academic-oriented research approach to your topics. What did you study at the Sorbonne?

Barrada: I studied history, so with this methodology, I know how to do research, but I have a more inclusive and playful approach, too. I’m looking for new forms. Yet I have a wide scope in terms of forms because I’m always looking for the right shape to transform what I find.

But to get back to photography—on this filming trip, I was interested in the fact that I was totally illiterate in trying to decipher and read the extraordinary landscapes we saw, between the Atlas mountains and the desert—illiterate compared to a geologist, a paleontologist, or a local shepherd who sees so many stories in those rocks.

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Painted Sign series, Rock Shop) 2013–15

I would regularly ask my companions on our mission to describe what they saw. The paleontologists, for example, they see everything as if it was still underwater, so it was quite wonderful: the poetry of the scientific vocabulary is unlimited, you get any lithology book, and you just jump in. Or even a book on textile history. I was looking at a catalog and there was this whole thing on telling muslins apart. And there was this sentence that was incredible: “Muslins are made by walking.” I just want to put that in the middle of one of my texts! They’re talking about the way the fabric is made; I don’t know what “walking” means, technically, but it means something in the weaving industry, do you see what I mean?

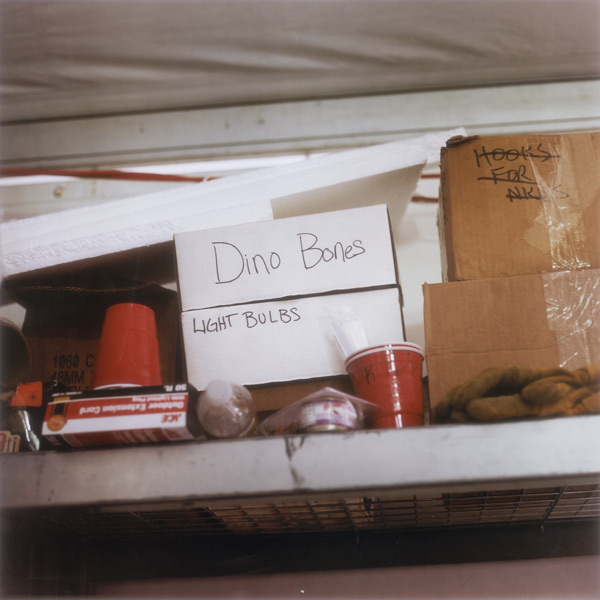

Yto Barrada, Untitled (Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show series, Dino Bones, Arizona), 2014–15. All photographs courtesy the artist; Pace Gallery, London; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut and Hamburg; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Maturo: Why is it that a lot of people don’t know about dinosaurs in Morocco?

Barrada: A lot of people do know, but they’re either specialists or local bureaucrats or kids. I’m saying there’s no instrumentalization by the state and that is odd. No airport posters, no school posters, no hotel posters. That’s why I made the series of posters, I made the communication—that’s material you can have. I made the toys for the museum so they’d be ready the day the museum opened, because you know that in the modern museum, if you don’t have a boutique, the museum will not survive.

Dinosaurs and fossils are fascinating to me because they involve fiction, forgery, tourism, and economy. You have something that has philosophy imprinted, and then you have the story of imprint—the imprint is like photography. Strangely enough, a fossil is a mold-and-a-cast all by itself; the fossil is already an incredibly faithful copy of the prehistoric creature.

There’s this thing in Morocco around filming or taking pictures—there’s this silly dogma of giving a “positive” image. I’m attracted to the other image, the bandit, the “faux guide,” the magician, the underdog, and the smuggler. In most of my films, the characters I chose are mostly figures of resistance. In a situation of domination, I am interested in how you find a way to keep your head up. Humor is one way; ruse is another.

Nicole Maturo, a former work scholar at Aperture magazine, is an executive assistant at the Aperture Foundation.

Yto Barrada’s exhibition Faux Guide will travel to Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut from May 26 to August 1, 2016, and to The Power Plant in Toronto, beginning in October 2016. A Guide to Fossils for Forgers and Foreigners will be published in spring 2016 by Walther König.