Publisher's Profile: Ruben Lundgren in conversation with Yuan Di, Jiazazhi Press

On a smoggy afternoon in Beijing, I meet with Yuan Di for a chat about his independent publishing house, Jiazazhi Press. We meet at the restaurant Timezone 8, which was once home to Beijing’s first specialized art and photobook store, as well as the influential Timezone 8 publishing house, run by Robert Bernell. Bernell gave up publishing a few years ago, around the same time that Yuan Di started. The thirty-two-year-old is based in Ningbo, a city just south of Shanghai, where he runs a small photobook store and will soon launch a photography magazine, both under the name Jiazazhi. Yuan Di seems somewhat shy upon first impression, but he is a man with a clear mission: to bring the Chinese photobook scene to a higher level.

Ruben Lundgren: How did you start your career as a photobook publisher?

Yuan Di: In 2007 I started a blog called Jiazazhi. The word jia in Chinese means “fake,” and zazhi means “magazine.” I used the word fake because my feeling toward the online platform was that it was somehow not quite real. At the time I was working as an editor for O2, a bilingual cultural magazine, and later for the Outlook Magazine. But I felt the need to work for myself. Although I started as a photographer, I quickly gave up that idea when I saw the high quality of work being made by others. I felt the desire to help introduce their work to the rest of the world.

RL: What was the first book you published?

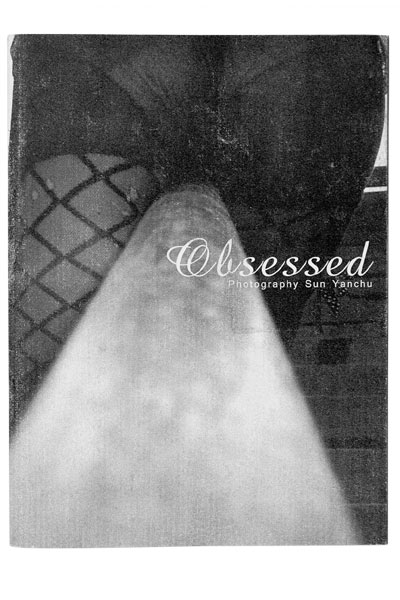

YD: That was in 2011, a book called Obsessed, featuring the work of Sun Yanchu. Sun Yanchu and I were friends, and he gave me a copy of a photocopied book that he made himself in a small edition. It was a bit of a coincidence, really. I decided to help him make an offset book out of his dummy, with the same title and roughly the same edit, in a print run of five hundred copies. Although it was a relatively cheap book to print, it was a lot of money to me at the time. But I remember I made a calculation that we would be able to break even if we sold it for about $10 [U.S.] a book. The most popular platform to promote the book was [the microblogging website] Weibo, and of course the Chinese equivalent to eBay, Taobao. The book sold out within a few months.

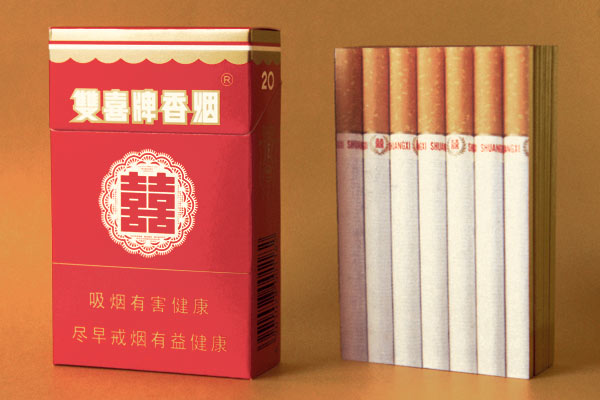

Sun Yanchu, Obsessed. Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China, 2011

RL:Was it a big step to give up your job at the magazine and become a full-time publisher? I can imagine your family might have had doubts about this step away from a fixed income.

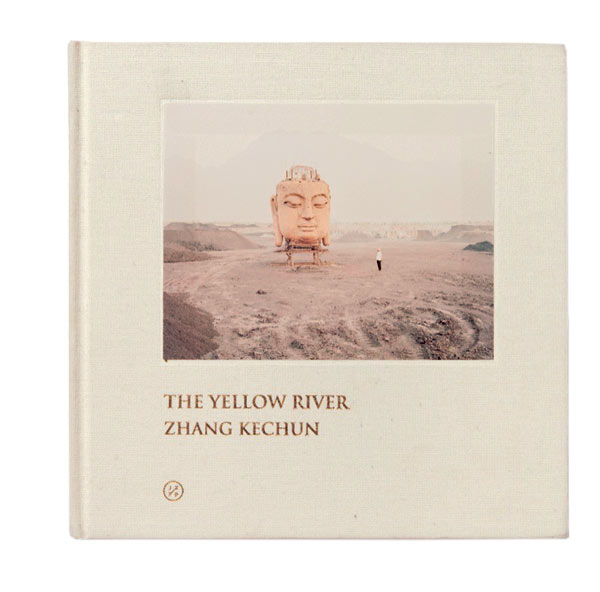

YD: Yes, absolutely, especially because it was just after my son was born in 2012 and I had moved back to Ningbo. But I had a clear desire, a dream, to become a publisher myself. One part of that was to help out friends, but most important, I wanted to make real books by myself, with photography that interested me. Before I started I made a calculation of potential business, and I strongly believed that I could make it, based on successes like Obsessed and They by Zhang Xiao [another early book]. I have been lucky with some books. In June 2014 I published The Yellow River, by Zhang Kechun. The month it came out we only sold thirty-seven copies, but a month later it won the Arles Discovery Award. People jumped on the book, and it sold out very quickly.

Zhang Kechun, The Yellow River. Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China, 2014

RL: In recent years you have participated in a number of international fairs, such as the New York Art Book Fair, Polycopies in Paris, and the Tokyo Art Book Fair. Why do we rarely see independent publishers from China at this type of fair?

YD: Well, I can only guess. The first reason is probably financial, as flights and hotels are expensive. But, more important, the idea that it’s possible to actually just do this kind of thing is not really present [in China]. There is not a big photobook market in China yet, and with my photobook ideas it can feel a little lonely sometimes. At the fairs I can share my experiences with other publishers from all over. It’s more than just the money—it’s really like a family setting. I was the first independent publisher from China to have a booth at the NYABF. People seemed to be surprised and kept asking me if I was from Taiwan.

RL:Would that be because, especially in recent years of political change, it has actually become harder to be an “official” independent publisher? Your ISBN, for example, is registered in Hong Kong and not on the mainland.

YD: Yes and no. It has always been very clear that as long as you don’t cross the line, it’s OK to publish independently. The problem is that even officials often don’t know what that line looks like and where to draw it. I recently talked with the head of a major publishing authority, and he said he had been following my publications for years and liked them very much.

Thomas Sauvin, Until Death Do Us Part. Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China, 2015

RL: What is your take on the contemporary photobook market in China?

YD: It’s still a very traditional market, with opportunities to sell classic works from photographers such as Robert Frank and Daido Moriyama. My belief, however, is that the market is a little bit self-fulfilling. The assumption is that the market is keen on these traditional works, therefore publishers import or produce books that are like those books—and therefore the audience is not exposed to a wider perspective on contemporary photobook publishing. I see it as part of my job to introduce a larger variety of books. This is also the reason I’ve started to distribute books from other publishers. I think the reason is not that people don’t want to buy these books, but that those who supply the market are too conventional in their thinking compared to how smart the audience has become.

RL: What does the future hold for Jiazazhi?

YD: We recently published two new books, Fountain by Cai Dongdong and Qu Jing by Lin Shu, both very exciting. This year I am aiming to publish at least another five publications. Upcoming is the book Bees & the Bearable by Chen Zhe, designed by the awardwinning curator and designer Guang Yu. Besides that, I am planning a new book with the photographer [known as] 223, and I want to publish the 3-D portraits that Matja Tani made in North Korea. I am also working on a Jiazazhi magazine. The first issue is organized around the theme “Untouched.” We have an interview with my hero Alec Soth, and will show the work of Chinese photographers such as Zhou Jungang and You Li. There’s so much to do!

Chen Zhe, Bees & the Bearable. Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China, 2016

RUBEN LUNDGREN is a Dutch photographer based in Beijing. He works in collaboration with Thijs groot Wassink, who is based in London, under the name WassinkLundgren. Their work together includes book projects, exhibitions, and photography commissions. They have produced over a dozen books, including Empty Bottles (Veenman Publishers, 2007), Tokyo Tokyo (Kodoji Press and Archive of Modern Conflict, 2011), and Hits (Fw: Books, 2013), and in collaboration with Martin Parr, edited The Chinese Photobook (Aperture, 2015), a history of photobook publishing in China since 1900. www.wassinklundgren.com