Separate Cars on the Open Road

Coinciding with Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, students in Sarah Lewis’s Harvard University class “Vision & Justice: The Art of Citizenship” contributed essays on the relationship between images of social unrest and landmark Supreme Court decisions. Here, Ian Askew reflects on Robert Frank and the freedom to travel.

On April 13, 1896, Supreme Court Justice David Brewer left Washington, D.C. for his home in Leavenworth, Kansas, following news of his daughter’s untimely death. In all likelihood Brewer traveled by train, and in a car for only white passengers. Meanwhile, in D.C., the case of Homer A. Plessy v. John H. Ferguson was being argued in front of the eight remaining judges. Given Justice Brewer’s record, it’s likely he would have sided with Justice John Harlan, the single judge to dissent in the seven-to-one landmark ruling that upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine and would define the partially reconstructed United States. This decision would cement that public, specifically mixed-race spaces would be accessible but inhospitable to black citizens of the United States. For black activists, the ruling instilled a narrative that citizens seeking equality should do so through desegregation and by gaining access to shared facilities. Plessy sought to give black citizens the same kind of access to transportation, and therefore the nation, enjoyed by Justice Brewer.

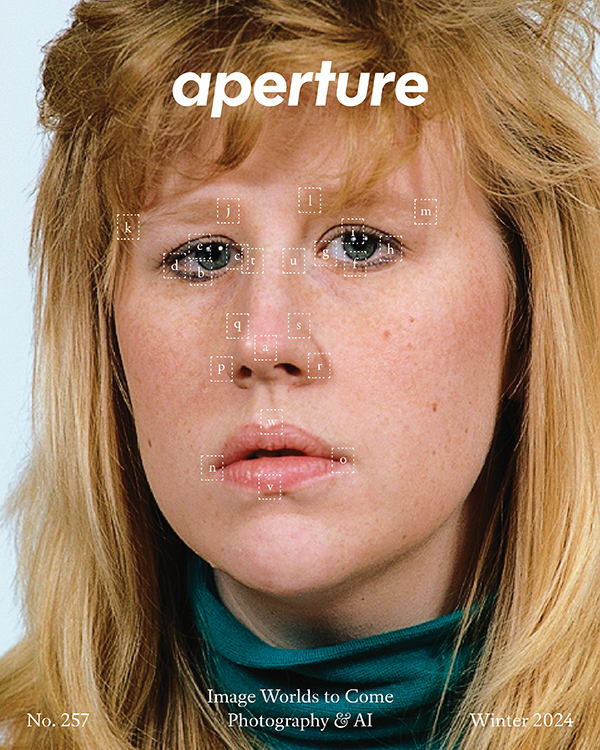

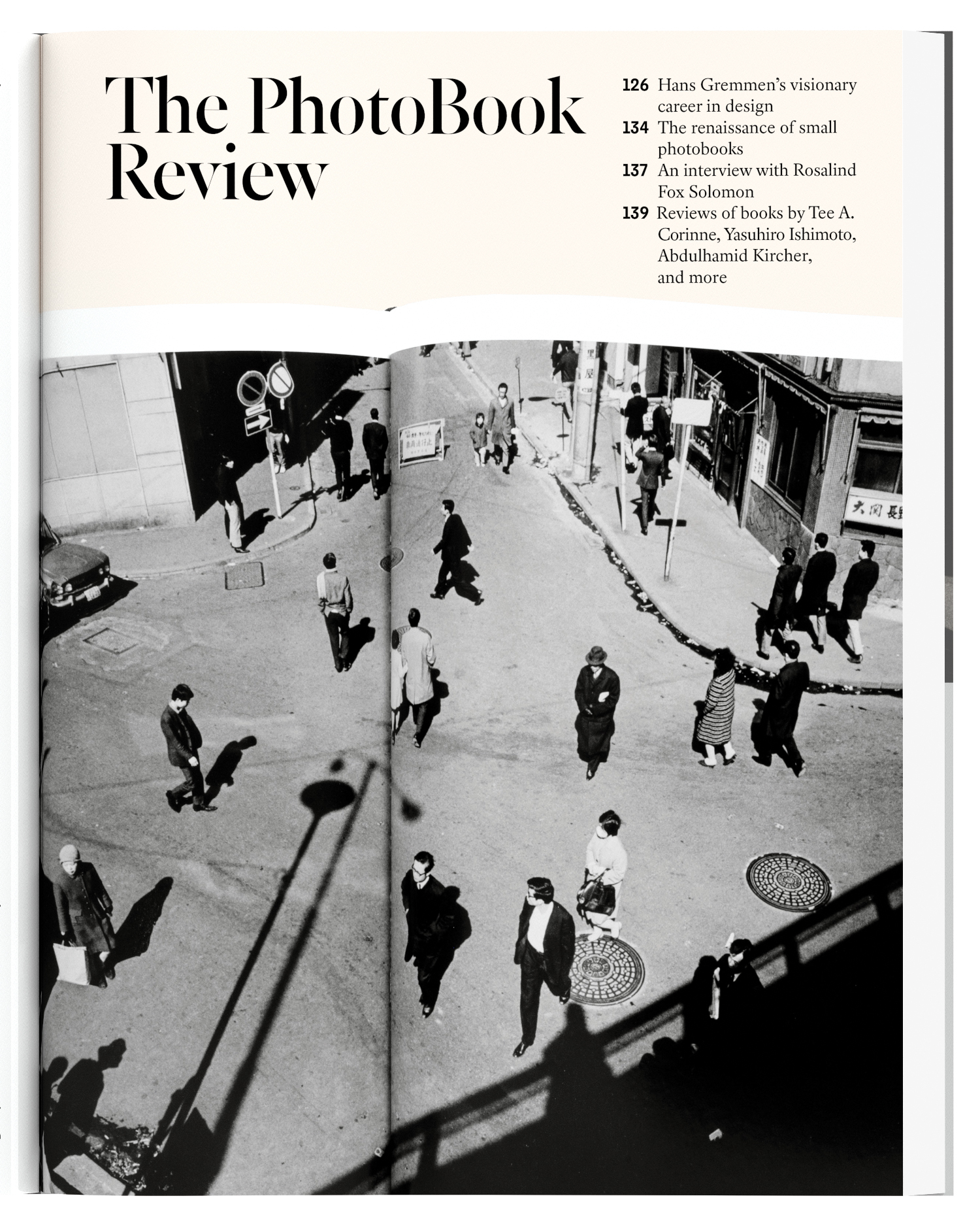

Nearly sixty years later, in 1956, as Rosa Parks continued Homer Plessy’s legacy by fighting for equal access to public transportation in Montgomery, Alabama, the Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank visited Indianapolis, Indiana. Frank was there capturing images that would eventually be collected in his landmark 1958 photobook, The Americans. The book was a revelation to many, and featured images of the country as seen through a foreigner’s eye. Frank captured the essential complexity of American culture, a vision not advertised to the world, and revealed the growing pains of a country still in transition.

Frank’s 1956 image Indianapolis provides one of the book’s many revelations. His portrait of a young black man and woman, presumably a couple, presents a starling portrayal of black aspiration and style. Two young people sit astride a motorcycle. In their posture and downcast eyes, they perform a brand of coolness that seems to predict the aesthetic of the Blaxploitation films that would follow in the 1970s. Light darts off of the studded shoulder of the driver; the man and woman appear fused to the machine. The couple’s focus beyond the frame allows the viewer to consume their coolness, their modernity, their self-possession without meeting or confronting their gaze.

Frank’s image asks nothing of the audience but their attention. At the time, images of black neighborhoods and segregated public spaces, purveyed by popular media, served as “proof” of the failings of segregation, and argued that separation was tantamount to the death of black potential. Frank’s photograph does none of this. Instead, Frank pictures black people on their own terms, embodying the potential of travel—that most American ideal of freedom. They are not Plessy insisting on a place in the train car or Rosa insisting on a seat on the bus. They have a machine, and they’re ready to claim the open road.

Ian Askew studies history and literature at Harvard University.