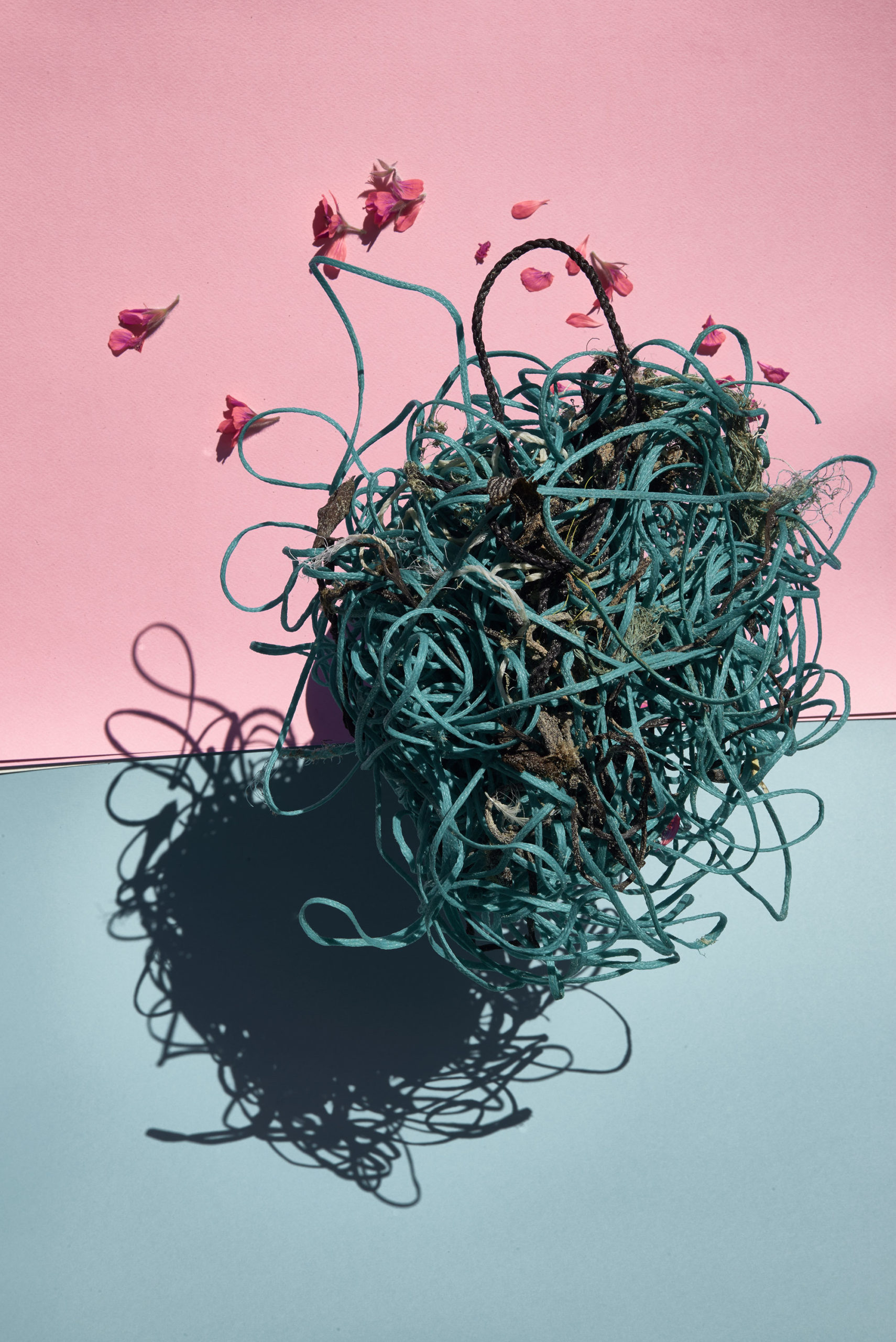

Thirza Schaap, Beehive, from the series Plastic Ocean, 2017–ongoing

From her home in Cape Town, where she’s lived for the last six years, Dutch artist Thirza Schaap can walk to the ocean in seven minutes. The waters are wild and cold there, too rough for leisurely swimming. Drawn to them nonetheless, Schaap began walking the beaches with her black-and-white poodle, Iso, and was struck by the perpetual mass of plastic debris washing up on the shore, often caught up in watery strands of seaweed. It always looks, she says warmly, “like there has been a party.”

Courtesy the artist

In 2016, Schaap started photographing found plastic sculptures and sharing her pictures on social media. As response to the work grew, she carved out a daily habit, foraging for plastic while out on morning rambles, then going home and making fanciful, pastel-hued arrangements on a table in her garden, and finally photographing her impromptu sculptures. Her lighthearted constructions contain familiar, everyday objects: bottles and lids, balloons, shoes, forks and spoons, toothbrushes, straws, and, of course, the ubiquitous plastic bag. Through Schaap’s collaboration with a writer friend, the resulting photographs take on evocative titles: Sunday stroll, Long stocking, Beehive.

Courtesy the artist

Despite their sweet allure, Schaap’s images are also deeply troubling. There has, after all, been a global party, and these pictures are glimpses of its ugly aftermath, shards of the unsustainable volume of refuse from our collective voraciousness. As sites of celebration so often appear the morning after, Schaap’s compositions are full of spent enjoyment, of things now devoid of use, faded, deflated, or broken. These things have been thrown away, but they persist, unable to decompose, resisting deletion.

Globally, we produce about 340 million tons of plastic each year, and a huge proportion of it ends up in our oceans. There are multiple “great garbage patches” floating languidly around Earth’s vast waters, the largest of which, off the coast of Hawaii, holds about 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic and weighs close to 80,000 metric tons. Like a large planetary orb, it continually pulls new objects into its sphere, perpetually accumulating remnants of our modern consumer culture.

Courtesy the artist

Schaap’s project Plastic Ocean (2017–ongoing) is a whimsical attempt to rescue a few stray fragments from this fate. A habit and a discipline, it has also become a meditative ritual tied to Schaap’s deep commitment to living a plastic-free life. Schaap, though, is not keen on pointing fingers or instilling guilt. There’s a groundswell now of antiplastic backlash, and Schaap finds inspiration in the community of people working to make things better. As melancholy reminders of the detrimental consequences of our entrenched habits of convenience, her images encourage the possibility, however inconvenient, of changing the way we live for the betterment of the planet and future generations.

Read more from Aperture, issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.