Essays

Black Style as a Form of Resistance and Joy

For Aperture’s summer issue, “Liberated Threads,” guest editor Tanisha C. Ford explores fashion’s ability to create possibilities for solidarity and selfhood across the African diaspora.

© Kwame Brathwaite Estate

MELANIN ABUNDANT. The dark lenses of South African activist Amonge Sinxoto’s Black Vibe Tribe sunglasses obscure her eyes. The message, written on the frames in white block text, speaks for her. Sinxoto’s pride is so uncontainable it bursts through her dermis. Holy Ghost dances on her melanated skin. It’s an offering. We give thanks.

The Kenyan-born, Johannesburg-based Cedric Nzaka (who runs everydaypeoplestories, the popular photography blog) snapped this image of Sinxoto at the 2018 Afropunk music festival in Joburg. By composing the portrait around Sinxoto’s face, Nzaka enunciates the power of Black abundance. It’s in the architectural baby hairs, the Senegalese twists that expand into a low Afro puff ponytail, dainty pearl earrings, and the headdress—designed by the South African hair artist Nikiwe Dlova—that resembles a helmet (it can also be worn as a Zulu-style crown). Dlova’s technique of affixing hair over flexi rods offers a new take on the now-iconic hair-in-rollers aesthetic, elevating it from a pre-style to royal wear. The photograph is simultaneously vintage and futuristic, dainty and militaristic.

© the artist

© the artist

It’s the circles. On Sinxoto’s shades, on the headpiece. They offer a Global South Black girl geometry that emanates from the ancestral soil and conjures itself into a way of knowing that is equally artistic and mathematical. A geometry that imagines new theorems for new worlds. A cosmology, flexible like the rods on Sinxoto’s crown, bending and folding time. MELANIN ABUNDANT.

Fashion has never been trivial for people of African descent.

It is an act of personal expression.

A pleasure practice.

A ritual.

A political language.

A tool of resistance.

When I started writing about Black fashion over a decade ago, I was taken with the ways that Black women across the African diaspora incorporated dress into everyday acts of resistance in the 1960s and 1970s. Afros, dashikis, cowrie shells, and head wraps communicated something about their sense of self, pride in their Blackness, and an embodied vision of freedom. In the United States, they wore denim overalls in solidarity with Southern sharecroppers. In South Africa, they sported hot pants and brandished stiletto heels as weapons. In the United Kingdom, they adopted the leather jackets and berets of the US Black Panther Party. I was taken by what I identified as a cycle of pleasure, innovation, and social violence through which Black styles across the diaspora were fortified. Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (2015) was the book that emerged from years of research across three continents and a constellation of cities.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

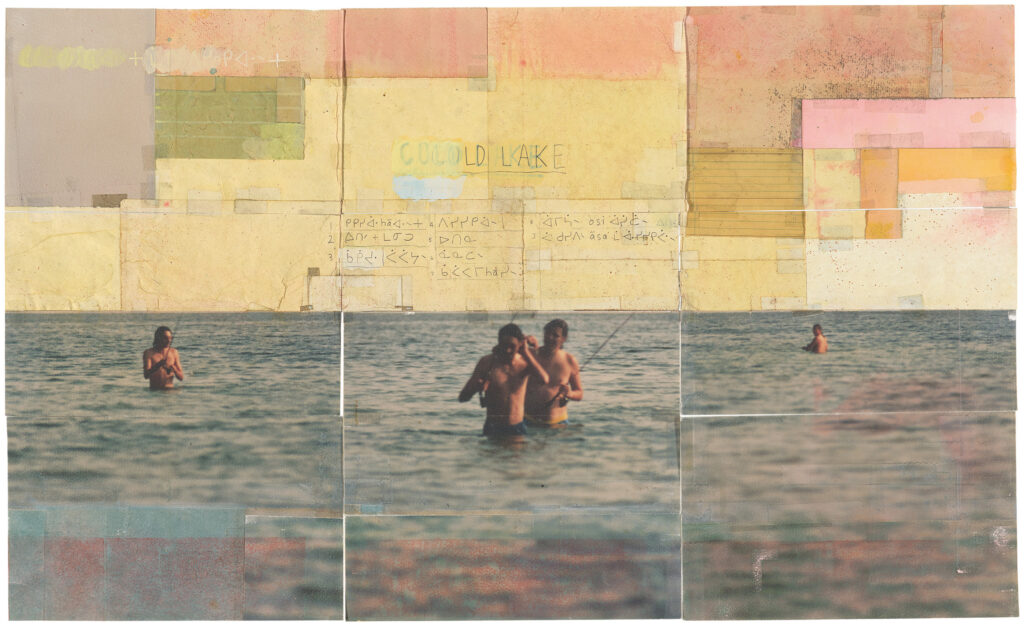

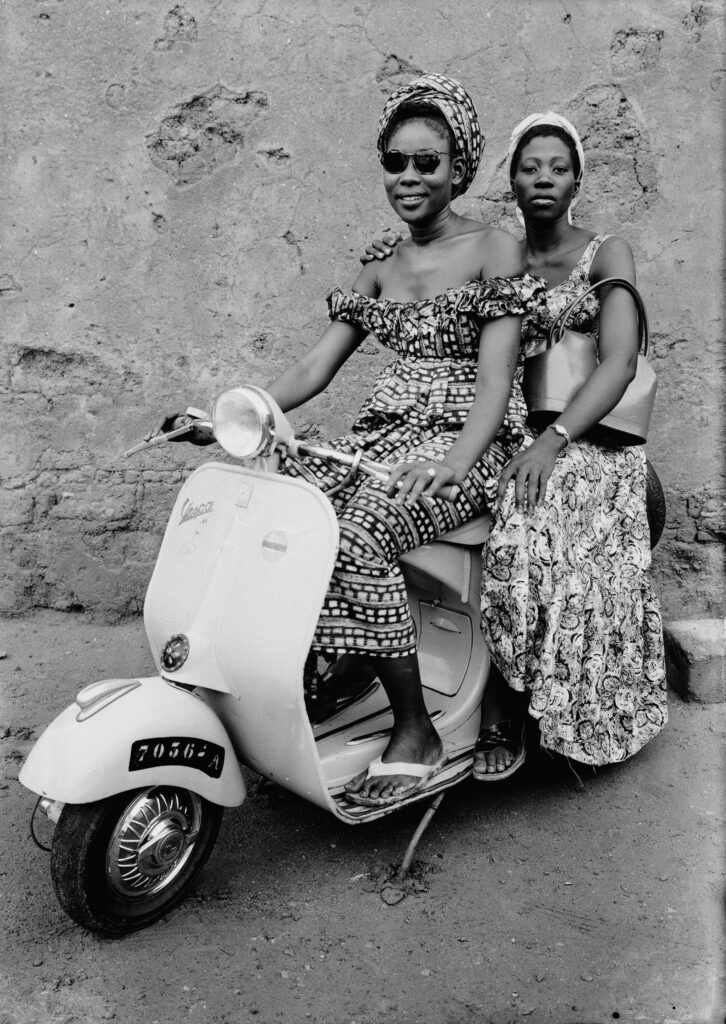

The “movement of movements” that shaped the 1960s represented the pinnacle of fashion activism. Radical activists; entertainers; fashion designers; and young students like my mother, Amye Glover-Ford, battled Jim Crow segregation, apartheid, European colonialism, and the afterlives of slavery. Their clothing became a uniform, armor in the struggle. As I excavated archives across the Black Atlantic, I stumbled upon the work of photographers such as Kwame Brathwaite, Malick Sidibé, James Barnor, Neil Kenlock, and Ming Smith, among many others chronicling this global movement. They used the fast-changing technology of the camera to capture the political imaginations and freedom dreams of young people of African descent, laid bare on garments and accessories.

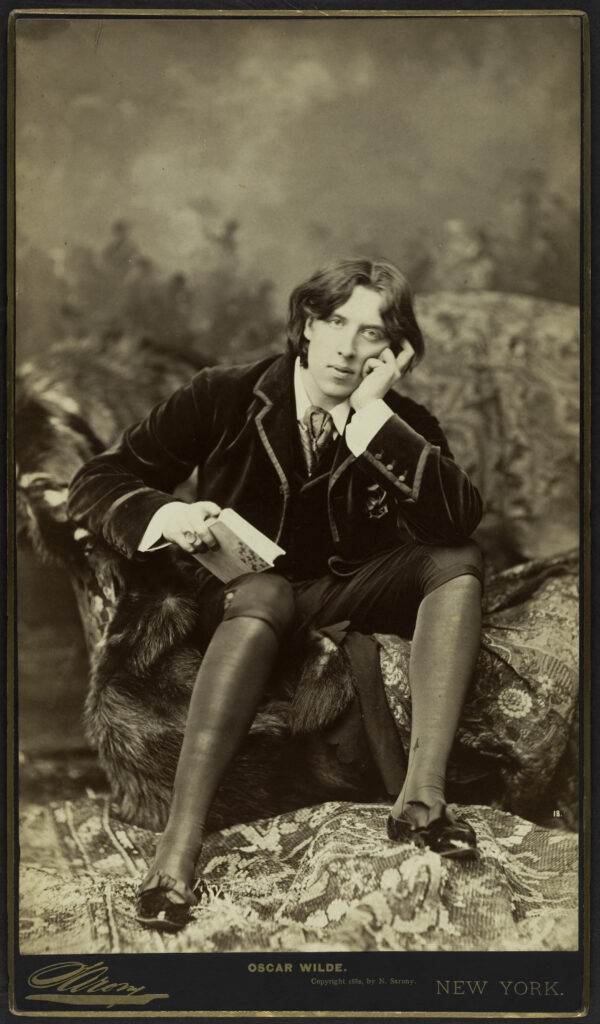

These photographs served as portals to an era. An era that for Gen Xers like me, was taught in US history classes and conveyed through popular culture as one of seismic social shifts and legislative changes, the likes of which we had never seen before and would never see again. But their rendering of the history was mangled and distorted. In these photographs lay another political reality. An episteme, a way of knowing a Black past through the practice of adornment. These images wrench the words style and fashion from the grips of the Western fashion world, which had proselytized and commodified them by linking them to conspicuous consumption and superficiality.

Courtesy the artist

Their messages were echoed elsewhere in my emerging Black style archive. In Black magazines—Ebony, Essence, Jet, Sepia, South Africa’s Drum, Flamingo, a West Indian magazine published in the UK—on jazz, soul, and funk album covers; and in memoirs, yearbooks, and personal correspondence. They told of underground African diasporic fashion economies that resisted capitalist impulses, with their own taste cultures, revered designers, tailors and seamstresses, second-hand markets, and politics of the liberated Black body.

I wanted to curate a visual conversation between Black image makers who are remixing, reimagining, and, in some cases, rejecting the aesthetics and political grammars of the 1960s and ’70s soul era.

I engaged in this form of deep study about Black style and its transgressive politics amid the “they sleep, we grind” culture that was social media in the early 2010s, tweeting in 140 characters about my archival finds. Like the rest of the world, I became enamored with posting selfies on Instagram. We were amateur photographers. Playing with aperture and saturation until our self-portraits were soaked with color, so wet they bent reality. Auteurs making filmic shorts for Vine with our smartphones. Bleaching out the edges, blurring, shadowing. Filters as play. A digital visual language.

As 2011 folded into 2015—the year that Liberated Threads was published—my tweets and IG posts became more enraged and furious as a large-scale Movement for Black Lives unfurled around me. Names of Black folks of all genders memorialized on T-shirts, their names linked with the & sign. Hashtags proclaiming #blacklivesmatter, #sayhername, #handsupdontshoot. Viral videos of the Black massive taking to the streets in protest, dancing and screaming to Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 anthem “Alright”: We gon’ be alright / We gon’ be alright / Do you hear me, do you feel me? / We gon’ be alright.

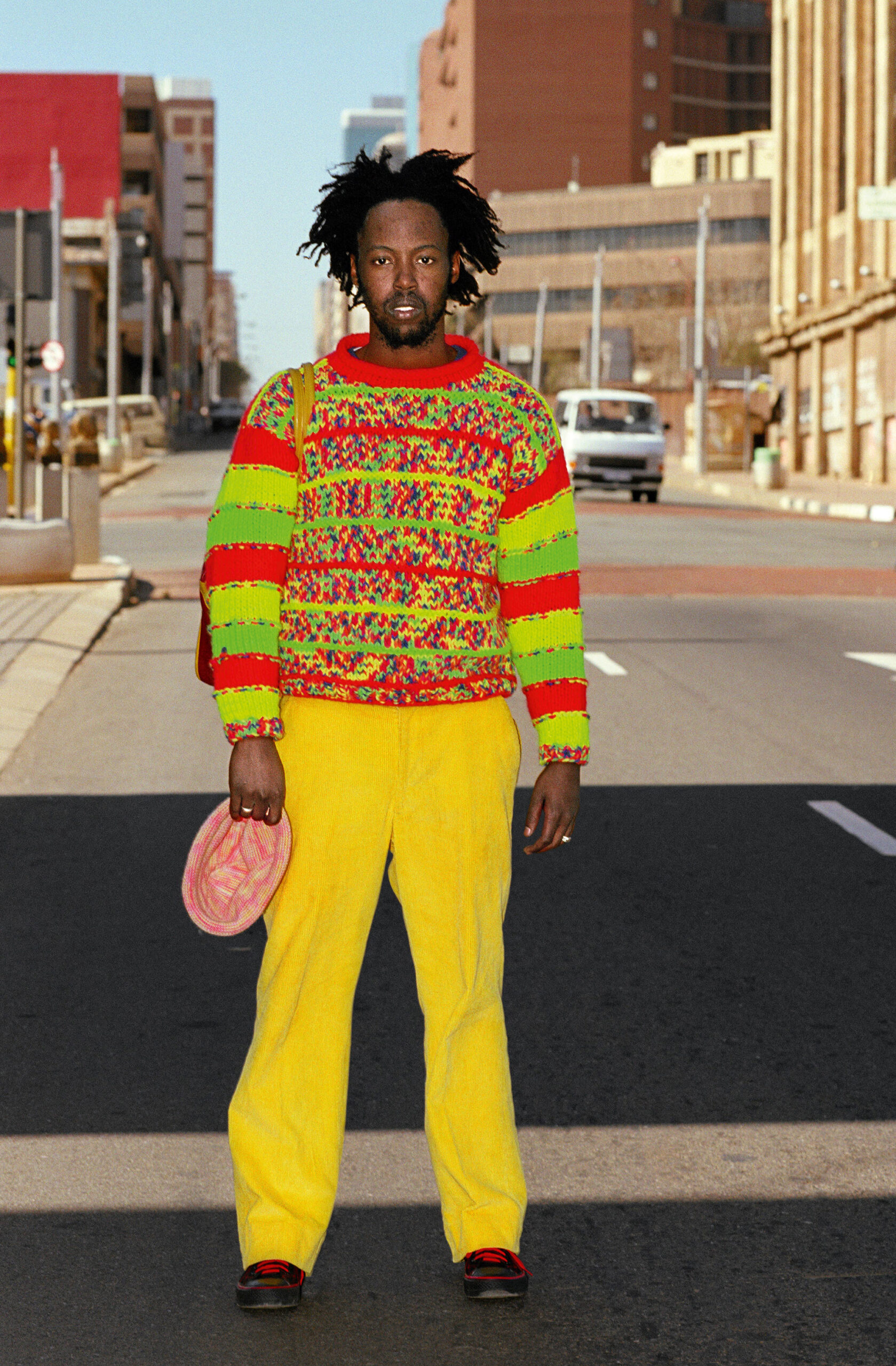

We were living through an immense social and political uprising to end anti-Black violence in all forms. Suddenly, the book I’d written was not about the past in the ways my teachers had presented it. Liberated Threads was living history. Just like the young people of the 1960s and ’70s used clothing and accessories to define the contours of their movement, chanting “Black Is Beautiful” and “The Revolution Has Come,” folks in the 2010s were too. In the United States, hip-hop fashions (a direct middle finger to “respectability politics”) were garments of choice. Skinny jeans and joggers, hoodies and screen-printed T-shirts, snapback ball caps, Jordans, tattoos and piercings, box braids with Kanekalon hair in the colors of the rainbow, and hoop earrings. A new generation of documentary photographers—including Andre Wagner and Devin Allen—were recording the moment.

It’s a moment we still have not had time to process, to fully understand. A moment that was punctuated in many ways by the pandemic. A calendar of death marking time as we marched into the turbulent 2020s. When latex gloves and face masks became an essential part of our everyday attire. When grind culture was replaced by “soft life” and “rest is resistance.” We were gearing up for an even bigger fight.

Ten years after the publication of Liberated Threads, the world is still on fire. It is time to revisit the concept of style as resistance across Africa and its diaspora.

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière

Courtesy the artist

But this is not a typical fashion issue. It does not aim to prove that Black people are stylish, with our own fashion ecosystems. It does not beg for Black people to be seen as beautiful, or human. It’s not a primer on Africana histories. It is a refusal.

I wanted to curate a visual conversation between Black image makers who are remixing, reimagining, and, in some cases, rejecting the aesthetics and political grammars of the 1960s and ’70s soul era. Liz Johnson Artur captures the beautiful clash of high fashion and London street style through the work of designers such as Feben and Mowalola, from Ethiopia and Nigeria, respectively. Interviews with director Melina Matsoukas and stylist Yashua Simmons—who are innovating in the commercial space—contrast with that between Ja’Tovia Gary and Fatima Jamal, who both subvert dominant narratives of Black life through filmic collages that experiment with the politics of form. Devin Allen offers us another way to think about protest photography, capturing activists in moments of joy or rest. Amy DuBois Barnett on the legacy of millennial lifestyle magazine, Honey, with its fly fashion editorials. The hair artist Nikki Nelms, whose work epitomizes the Black whimsical imagination. The generational influence of the Malian photographer Seydou Keïta, as seen in the work of Silvia Rosi and Nuits Balnéaires. This issue is on a mission to unearth unusual pairings, the Black uncanny. Images that disturb and confound vis-à-vis those that avail conventional visual tropes. Ultimately, I wanted to see what happens when we take the renegade tool of the camera—or what the historian Dan Berger calls “insurgent technology”—to demand answers of style. I wanted to hear from contemporary Black image makers about what’s at stake for Black communities today in the face of a rising tide of global capitalism and genocide. How have camera and film technologies made new modes (and nodes) of creative expression possible?

I hope this issue offers a metalanguage for people who are trying to make sense of the world. Who refuse to accept current conditions. Who dare to imagine a free, Black future. MELANIN ABUNDANT.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 259, “Liberated Threads.”