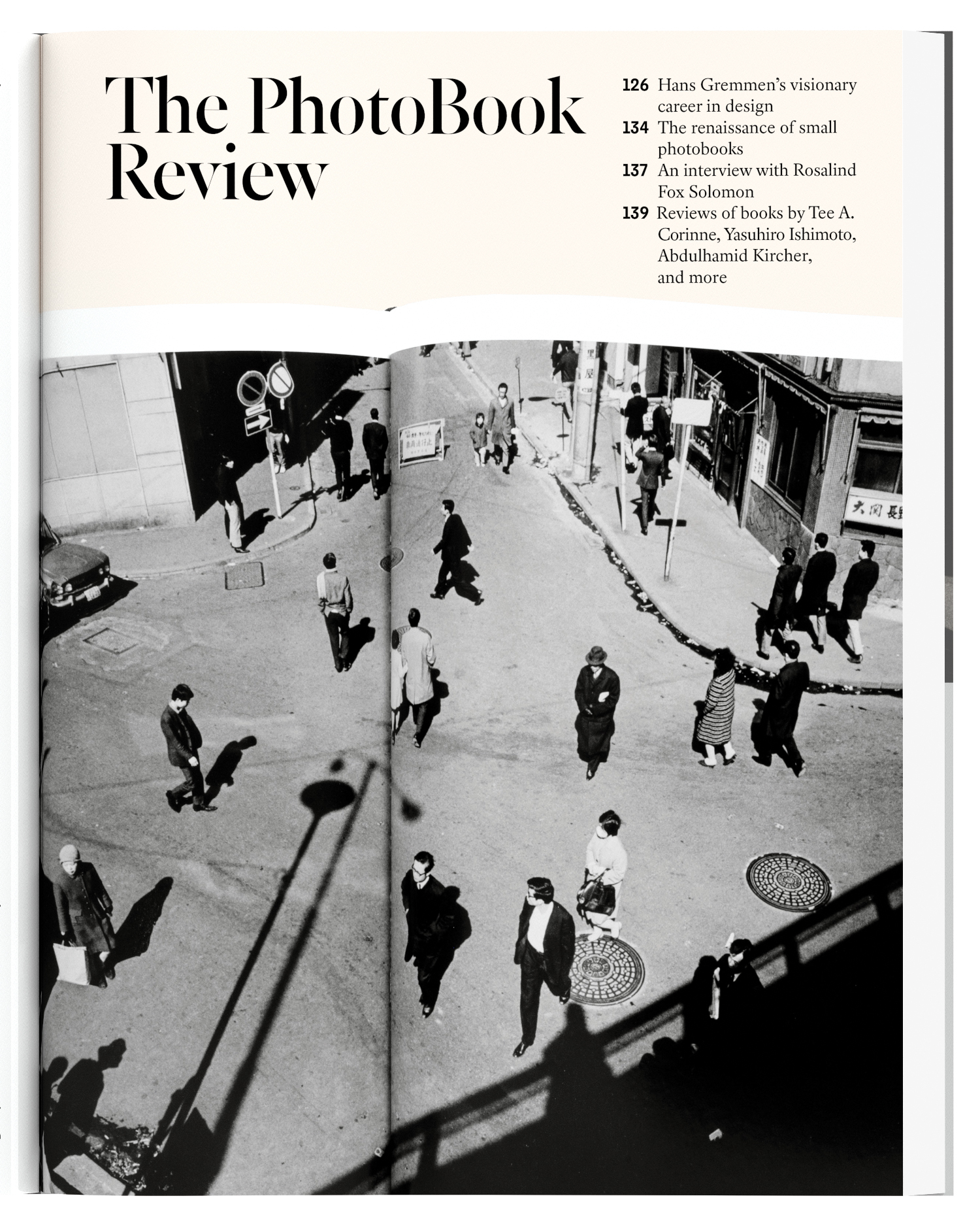

The Case for Digital by Simon Bainbridge

It’s been twenty-five years since Tim Berners-Lee proposed the framework for what was to become the World Wide Web, around the same time Thomas and John Knoll were finessing version 1.0 of Photoshop. Now we live in the digital present, connecting online as global communities; communicating via vast, interlinked networks that bypass geographic, economic, and sociopolitical boundaries; using photographs where common languages don’t exist.

And yet this was first published in a printed newspaper dedicated to photobooks in all their physical manifestations.

In the weeks and months it’s taken to put this issue together—from initial conversations between publisher and guest editor last September, to the final copy deadline in the middle of March, followed by the excruciatingly protracted process of reading, editing, subbing, designing, fitting, checking, sending, scheduling, printing, and distributing—countless brilliant and insightful thoughts about photography will have been discussed elsewhere. Many of these ideas were then typed out and, with very little additional effort, published online. Seconds later, they were being shared and commented on, instantly becoming part of a global discussion unencumbered by the need to deliver an object or commodity, far removed from the cliques and cloisters of photobook fandom. In a sense, the resurgent photobook is the perfect riposte to all this. Let’s face it: much of what we read online isn’t that enlightening, in part because of how easy it is to get thoughts out into the world. By contrast, the photobook is a fine example of slow publishing. It brings together artists and editors with highly skilled designers and makers to produce a tightly curated artwork in extended form, one which requires sustained time and thought from the reader, away from distraction.

But I’m concerned that our rediscovery of the printed book also plays to the conservative tendencies running deep within the photographic community.

Surely it’s no coincidence that while most of the world was ditching analog and using digital cameras to rediscover the pleasures of making pictures, art photographers were taking up large-format and hitting the road in their RVs once again. Photographers tend not to be great joiners; they’re usually outsiders looking in. So this early rejection of digital, with its ability to hasten and perfect the picture-making process, probably came from a more radical tendency, an independent streak that was alarmed by the sudden ubiquity of digital SLRs.

This impulse to opt out leaves photography with nowhere to go but backward. Likewise with the book; rather than exploring how digital could expand the form, and taking advantage of these new tools to tell stories and extend artistic practice, we are in retreat. And instead of embracing the opportunity to reach new audiences, we have retrenched, operating in a closed loop that may seem dynamic now, but risks losing relevance to anyone less wedded to the physical book than we are.

I am curious about all this because the arrival of the iPad four years ago gave us the ideal vehicle with which to develop a new language. Tablets bring together the best of the digital realm—its dynamic, instantaneous, interlinking, multimedia forms—with all the accumulated skills and knowledge brought to bear on print over the past five hundred-odd years.

This was certainly our experience with the launch of an iPad version of British Journal of Photography, with which we doubled our subscription base in two years; we are now building a global readership. For the first time ever, we could take our skills to the digital screen to produce something much more cohesive and elegant than we ever could online, bringing the printed page to life with the addition of video (just as photographers were given easier access to filmmaking when broadcast-quality motion capture was added to DSLRs) and intuitive navigational devices that, because they are tactile, are somehow more personal.

So why haven’t we seen the same dynamic in photobook publishing, where the lead times give greater room for experimentation, and the imperative to find wider readerships is even more urgent? There may be worthy intentions behind them, but most of the digital photobooks we’ve seen so far have been terribly dull, failing to advance beyond the printed page in any significant form.

Some of the reasons are economic. Digital publishing isn’t, as many believe, a cheap option. You need to invest time and money setting up, and you more than double the workload by adding a digital format alongside an existing print workflow. There’s something of the dark arts to getting publications through the Apple approval process; visibility for your books on the iTunes storefront is a major challenge. And anything ambitious will require a programmer, which is beyond the reach of most small independents.

An early example of someone using the iPad to unfold a story in a way that would have been impossible in print is Vía PanAm, photographer Kadir van Lohuizen’s investigation of the roots of migration in the Americas, first released as an app in 2011. It brings together the stories of the people he encountered on his nearly 16,000-mile trip from Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of South America, to Alaska. Vía PanAm remains one of the more innovative photography projects to date, using digital publishing and multimedia to explore new narrative possibilities. Van Lohuizen updated the app as he went along, adding text, audio, and pictures during the twelve-month journey in something close to real time. It cost tens of thousands of euros to produce and, despite substantial backing, wasn’t much of a commercial success. Nothing as ambitious has been attempted since.

Even more damaging than the cost is the general sense of apathy toward digital publishing—and the resurgence of the printed photobook is to blame. In our ever-more-cozy relationship with the art market, the photography world has become obsessed with the idea of the limited-edition object. The market demands artwork that is collectible, which means it must be both scarce and tangible. This is killing innovation in the digital realm. Photographers have no reason to invest in it and are seemingly too scared or too lazy to think beyond the ecosystem supported by galleries, who in turn are dependent on collectors who are innately conservative about how they attribute value.

Collectible books—special editions, multiple volumes—are now more financially sustainable than conventional print runs, even if they are priced high and reach far fewer people. Someone who’d been a major part of this model, but decided to address it, is London-based publisher Michael Mack, who says he doesn’t like the idea of merely collecting books instead of buying them on the strength of their merits. He has invested heavily into digital publishing, setting up the e-book publisher MAPP three years ago alongside the traditional book imprint that carries his name.

MAPP produced one of the more interesting digital photobooks yet seen, Jason Evans’s NYLPT, which features multi-exposed frames of overlapping images taken in New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo, as well as audio. In the printed version of the book, there is a sort of narrative structure to it, which Evans plays with in an attempt to interrupt the emerging logic. But it’s only in the digital version that his search for “chance, happy accident, luck” is given full rein, as each time the images and accompanying sound appear in a different sequence. The edit—the Holy Grail of the photobook—is never the same. What plays out is given higher priority than the artist’s ego.

NYLPT is a rare example of the digital version outshining the print, but it’s hardly the brave new world of publishing. For the most part, MAPP has excelled in bringing rare or unseen books into the public realm, such as Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux’s Atlas photographique de la Lune (a pioneering astronomical study of the moon, now rendered as photographs overlaid with semitransparent maps of the peaks and troughs of its surface), or the forthcoming version of William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, which is near-impossible to see in its original form. It is scholarly ambition and a sense of egalitarianism that seem to drive Mack, rather than any desire to take the book toward new frontiers.

This is a small beginning. In the future, digital publishing will intersect with other new technologies, incorporating digital overlays, such as maps and navigational tools, with wearable devices offering the promise of “sensory fiction,” exploring the architecture of gaming environments, and segueing into augmented realities. And yet all that seems so far away. For now, digital photobooks are more of a theory than a reality, the promise of something to come. They have so far failed to seduce. The physical photobook brings together the collective know-how of artists, designers, editors, publishers, and printers, and when they work in harmony, they deliver so much more than the sum of their parts. What has the digital book got to offer instead?

The spell will only be broken if artists themselves begin to take the form seriously, working in tandem with publishers and developers to forge artworks that can stand alone. We need artists with the imagination and ambition of someone like Björk, whose Biophilia project reimagined the album as an interactive game. And we need a community to support them, with residencies and bursaries that encourage partnerships between artists and technologists, institutions that don’t look to the market for what’s coming next, and collectors that invest in artists rather than commodities.

That’s a big ask. But if digital technology is widening the frontiers of society, transforming the ways we live and communicate, it should be seen as a failure if photography is unable to reach beyond its historical confines simply because the established genres we operate in are so familiar. Photography as we know it, so often heralded as one of the youngest of art forms, is in danger of becoming antiquarian.

—

Simon Bainbridge became editor-in-chief of British Journal of Photography in 2003, steering the 160-year-old publication away from its uncertain future as a weekly trade magazine into a monthly that now goes out in print and digital formats. Based in London, he contributes to numerous awards as a judge and nominator (including the Prix Pictet and Deutsche Börse Photography Prize), and has cocurated two exhibitions: Paper, Rock, Scissors: The Constructed Image in New British Photography at Flash Forward Festival, Toronto, and Photography Beyond the Decisive Moment at Hereford Photography Festival, United Kingdom.