Essays

How Images Make the Objects We Desire Seem Irresistible

In the twentieth century, photographers proved you could sell anything. Today, they work in a world where you have to sell everything.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Imagine having lost a loved one in the New England of the 1870s. Then, a knock at your door: a salesman in a suit. He pulls out a bound catalog of albumen-silver prints, with as many photographs in it as you’ve maybe seen in a lifetime, each showing a tombstone ready to memorialize your loss. The trade catalog for the Vermont Marble Companies offers a purchase for your grief, documentation that something exists in the here and now to honor those in the here-after. This is an example of what the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s research assistant Virginia McBride calls “the truth claim of photography,” a way companies used the supposed veracity of photographic images to convince customers they would deliver what they promised.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It’s an early highlight of a Met show on view this summer that McBride has curated, The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography, which tracks how pictures made people familiar with objects for consumption and then, with the arrival of modernism, rendered such objects radiantly unfamiliar. The show, which features work from the nineteenth century to the late 1940s, arrives at a moment when many artists have been drawing inspiration from the long history of how photography has been used to sell all manner of commodities. It’s a moment marked by a turn from the object for sale to the meaning of the sale itself.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

But first you had to make the sale, and the best way to do that was to catch someone’s eye. A commercial photographer in Providence, Rhode Island, named H. Raymond Ball photographed a comb from an unknown manufacturer balancing mysteriously on its edge; in his Pocket Comb (ca. 1930s), the expanse of the object’s shadow somehow echoes both the architect Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the bob hairstyle favored by flappers. “It’s an object lesson in what the camera can do with the right light and the right shadow and any object at all,” McBride explained.

Corporate resources funded adventurous photographers to push things even further. Edward J. Steichen was commissioned by a Swiss textile manufacturer to lend their products a touch of the new. His “Sugar Lumps” Pattern Design for Stehli Silks, from the 1920s, staggers rows of the treat to cleverly arrange their shadows into a fresh take on a checkerboard; in 1927, Stehli made a textile with Steichen’s photograph printed upon it, and the advertisement itself became the product.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

August Sander went even further. For Osram Light Bulbs (ca. 1930) he composed a spiral of lightbulbs, creating a gelatin-silver print that seems lit vertiginously from within. If the bulbs could do that on a magazine page, what wonders they might lend to your house! In such advertisements, photography transcends its lifelike authority to become life itself, abuzz with a kind of optimism some Americans in the 1930s and ’40s might’ve found lacking in their daily lives, as they flicked through Depression-era fashion magazines and war-stricken newspapers.

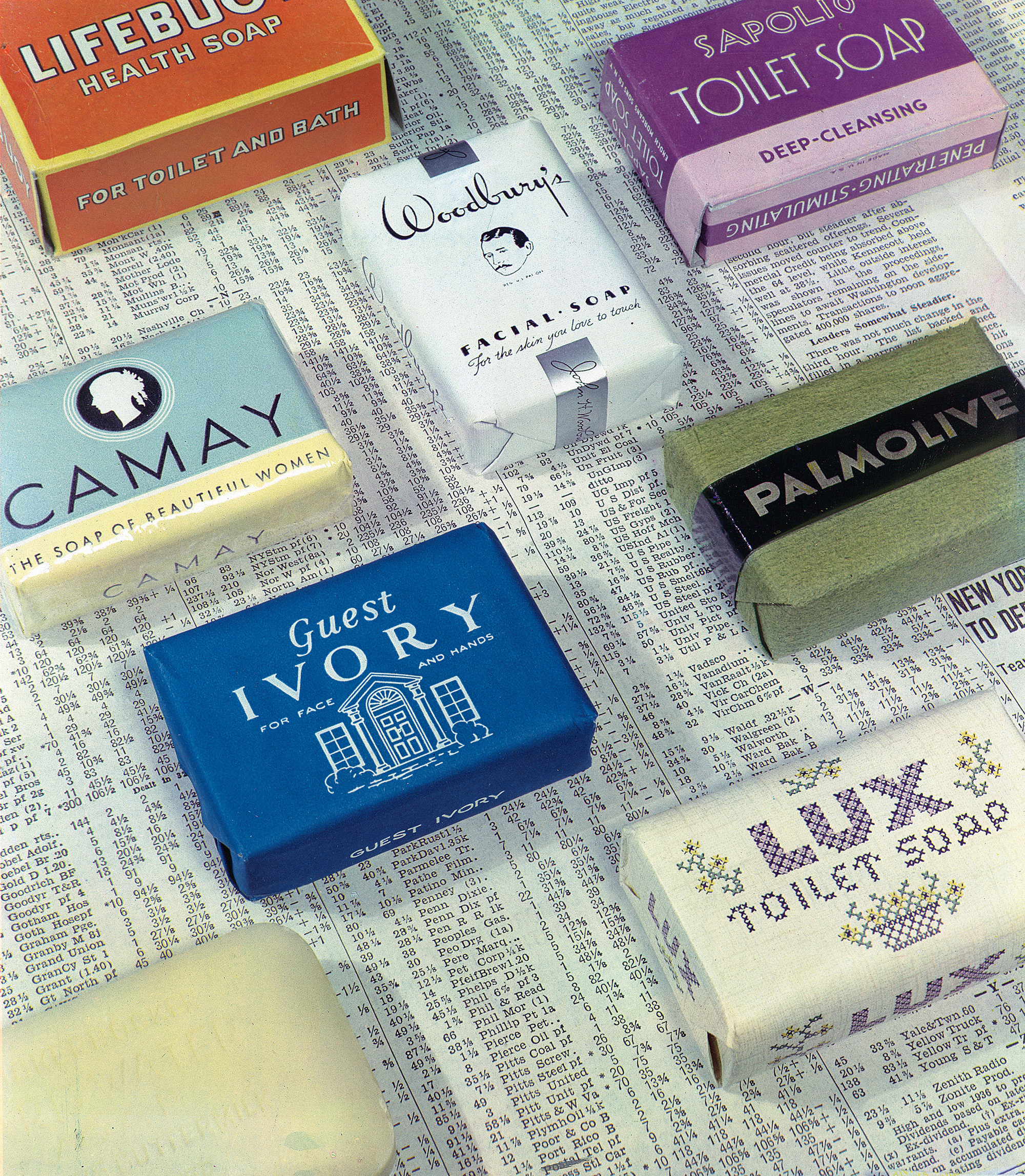

Ralph Bartholomew Jr.’s carbo print Soap Packaging (1936) erects a cityscape of candy-colored packaged soap on newsprint in a bubbly anticipation of Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie six years later. An unknown image maker gassed up a car ad with the latest editing techniques for Montage for Packard Super Eight (ca. 1940), which you can imagine zipping around that soap package city, even if that many people couldn’t possibly fit in a Packard that size. Modernism, with its emerging formal concerns of experimentation and abstraction, was an irresistible tool kit for a sales pitch.

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This fizzy blend of commercial seduction and fine-art methodology reached a peak in the pages of Vogue, which commissioned Irving Penn’s Theatre Accident, New York (1947). “It’s not usually talked about as a product photograph, but rather sort of the be-all and end-all of photographic still lifes of the twentieth century,” McBride said. And yet, every object spilled from that purse is available for purchase—and has been purchased by the sophisticated kind of woman Vogue suggests you should be. “The idea that these amalgamated objects can really create an entire personhood is very explicitly spelled out,” she added. “Even with these inanimate objects, [Penn] could conjure a living, breathing woman.” In the eighty or so years between the tombstone catalog and the Vogue masterpiece, photography moved from the lifelike, to larger-than-life, to having the ability to conjure up life itself.

Modernism, with its emerging formal concerns of experimentation and abstraction, was a tool kit for a sales pitch.

And what happened in the many decades after the photographers shown in The Real Thing? Contemporary image makers—who are outside the focus of the museum’s presentation and the heirs to its heroes—grew up in thrall of the earlier history it explores. They now live and work in a world of hyperconsumerism, advertising, and targeted marketing that those photographs, and the related capitalist machinery, helped to build. The exhibition’s checklist offers a prompt to consider how they made sense of the tug and pull of art and commerce within a picture frame or, increasingly, the social-media grid.

Courtesy the Irving Penn Foundation and the Metropolitan Museum ofArt, NewYork

Courtesy Loose Joints

“Sometimes it feels like all I’m really looking at is this strange reflection of what happens when a person is fed advertising their entire life and, weirdly, fetishizes it,” the photographer Bobby Doherty told me. His images—from eye-popping sweets and consumer goods of clients including Balenciaga and Apple to the still lifes filling his recent photobook, Dream About Nothing (2023)—draw on the legacy established by giants such as Penn but bring a sense of irony and intentional awkwardness. Doherty’s color palette is often hyperreal and exaggerated, but it can be muted to recall another era. “I just sometimes feel like there isn’t a new way to do it,” he said with a sigh. “The rules were really clearly laid out, and deviating from them just takes it to a place that isn’t advertising anymore.” His image Oronamin C (2022) features soda bottles and what appears to be a cheeseburger on a mirrored surface, and was inspired by 1960s food advertisements. The goal of his book, he added, was to create an experience of “subliminal advertising in a dream.”

For the conceptual artist Christopher Williams, histories of technology, production, and modernization are told through almost absurdist pile-ups of information, with captions elongated into campuses of text. His images re-create the aesthetics of a product photograph and the mechanics of image making, but often nod to political and colonial histories. His recent image of an IKEA kitchen treats a mass-produced interior model with a cartographical rigor you sense he might not quite think it deserves. Who would want to live in a world like this, with its banal perfection, the photograph seems to ask, while at the same time marshaling every resource of advertising. It’s less a swoon than a wink. Williams’s occasional photographs of models, seen in his work referencing a Kodak reflection guide from the 1960s, present them smiling broadly—a real no-no in the images used by fashion e-commerce sites, such as SSENSE, that feature both product and editorial. How could anyone in this world possibly be this happy?

The impact, emotional or otherwise, of accumulation seems to fuel Sara Cwynar’s work as she plumbs e-commerce spaces for evidence of what, or maybe how, companies think people want now. Which might just be more: yesterday’s brand catalog is today’s social-media feed, with endless scrolls of SSENSE or Shein items presented by similar models in similar poses. These posts could be purses spilling out glamorous contents, but there’s little personality on display.

Cwynar’s series Marilyn (2020) included photographs she took of SSENSE models in the company’s signature trio of poses, re-created on larger scales and with harsher lighting, as if trying to blow out the halo effect. “You can’t figure out what’s real, or what something actually looks like, or whether you’re looking at the same person or just the same image with different outfits photoshopped on,” she said. “I like the confusion of different styles of commercial photography in one thing. That kind of digital plenitude, there being too much to contend with, so everything starts to feel kind of valueless.” And yet value is in the eye of the beholder: Dior invited Cwynar to collaborate on a handbag.

© the artist and courtesy David Zwirner, New York

Courtesy the artist and the Approach, London

In the 1990s, such a collaboration might have been decried as “selling out.” At that moment—when international corporations were consolidating media into the hands of a very few, and the techniques of modernism had become all-too-familiar, even sinister—artists’ efforts to resist the collapse between art and product often felt noble. Even if, as the Met show makes clear, photographers were always working across contexts. Roe Ethridge came up in the ’90s moment when selling out might be taboo; today, with fewer markets for photography, he thinks that notion is passé. Instead, he trades on the notion of value, working for high-end fashion brands and showing the same images in high-end galleries. Confusion might be the point— or, perhaps, a tactic to wrangle with the challenges he sees in commercial photography. “How do I depict a handbag in a way that’s not untruthful to me?” he asked. “Which is a weird thing to think about. Why would I like or not like a handbag?” As Penn’s handbag does, Ethridge hopes his work “could live without the caption.”

These days, images live without all kinds of context, unmoored from their origins and floating freely across our screens. The photographers who made the images in The Real Thing proved you could sell anything; today’s artists work in a world where you have to sell everything. In the end, we’re left with the same question as that salesman at the door: What makes you pay attention? Product photography works—today, when we see too much, it lingers in our minds—because it tells us something about ourselves. It’s not about the product itself but what the picture produces inside you. It’s not a proof, but a mirror.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”