Is a British Exhibition About Resistance Stuck in the Past?

A nostalgic show curated by Steve McQueen about photography and protest misses the creative energy that drives social movements today.

Paul Trevor, Anti-racists gather to block route of National Front demonstration, New Cross Road, London, August 1977

Courtesy the artist

Close your eyes and contemplate the word resistance. Not the kind you had to your childhood homework or the weight of a dumbbell in your hand, but resistance in a political context, born from oppression and the need to fight against persecution. I played this game before a trip to see Resistance, an exhibition that was recently on view at the Turner Contemporary in Margate, England. Though I’m writing from a British context, I’d wager the mental images that come to your mind are similar to mine, all the familiar moments of collective struggle in the West: raised fists, workers with dirty faces, women in late Victorian garb, and throngs of protest crowds.

© Alamy

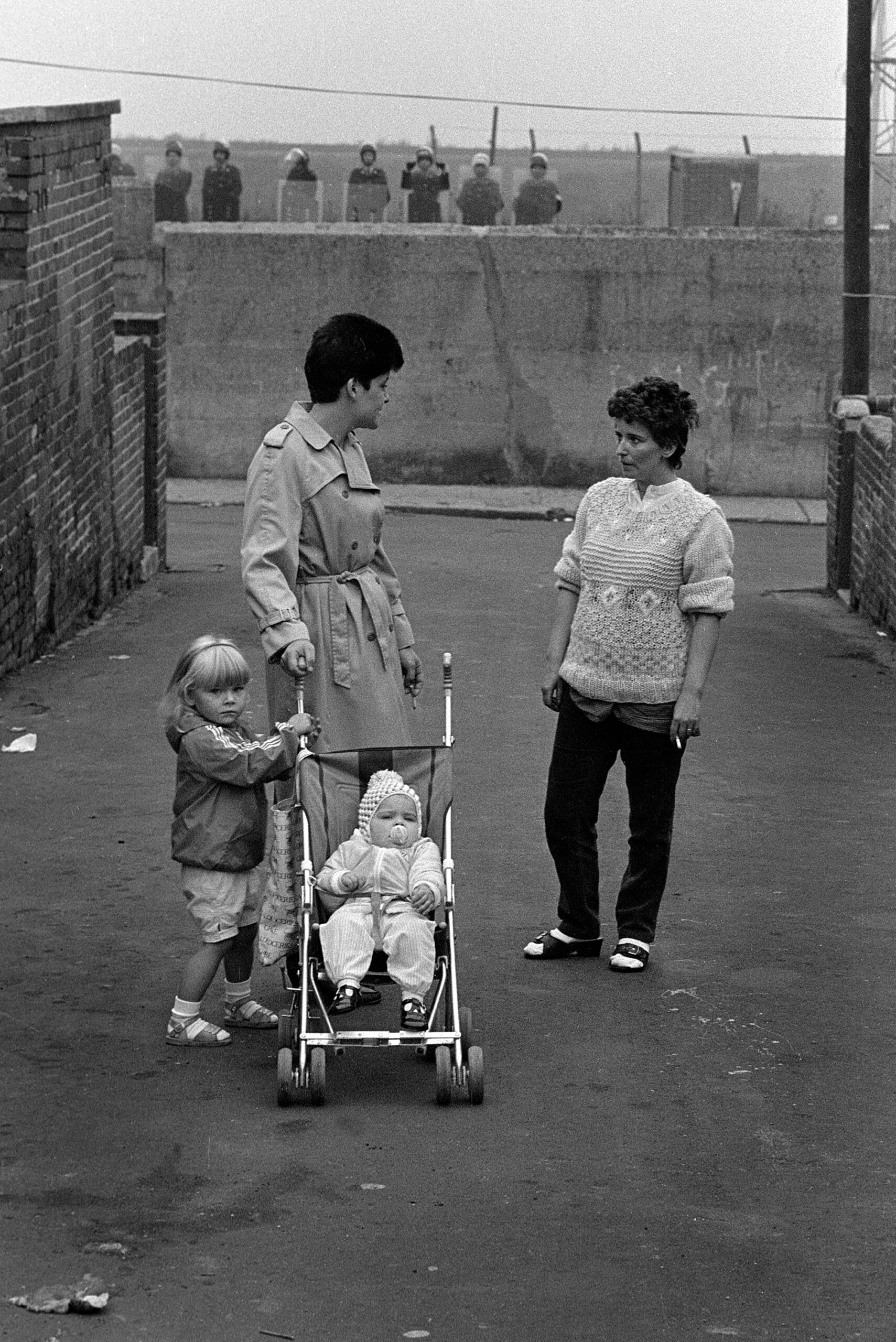

For Resistance, Steve McQueen, an artist who is best known internationally for his films Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), brought together photographs spanning one hundred years. Works started from the year 1903, which heralded the Suffrage movement for women’s rights, and ended in 2003 with protests of the war in Iraq. The exhibition and its accompanying book explore the ways that British people have “challenged the status quo.” Respected social-documentary photographers were featured, including David Hurn, a Magnum photographer known for his reportage across the United Kingdom in the 1960s; Janine Wiedel, who documented life in the industrial county of West Midlands during the same period; Vanley Burke, who captured the social awakening of Black Britons in Birmingham; and Tish Murtha, celebrated for her powerful depictions of working class life in North East England during the late 1970s and early 1980s. McQueen also leaned on the knowledge of a research group helmed by Paul Gilroy and Stella Dadzie to bring anonymous works and lesser-known events to the forefront, such as the National League of the Blind’s 1920 march—“a pivotal moment in the fight for disability rights” according to the show’s organizers—and the hunger marches of the 1930s, protests against poverty and high unemployment.

Courtesy the artist and reportphotos.com

But why did the exhibition stop in 2003? This is the year the writer Mark Fisher identifies as the end of the future—the point when neoliberal capitalism fully triumphed, ushering in what he calls “capitalist realism” and resulting in cultural stagnation. Smartphone footage of the 2011 London riots, Just Stop Oil demonstrations, internet-powered movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter—all missing from the galleries. In their absence, the exhibition lost the opportunity to connect modes of resistance in the old world and attempts at resistance in the new, when it feels like there are no viable alternatives emerging.

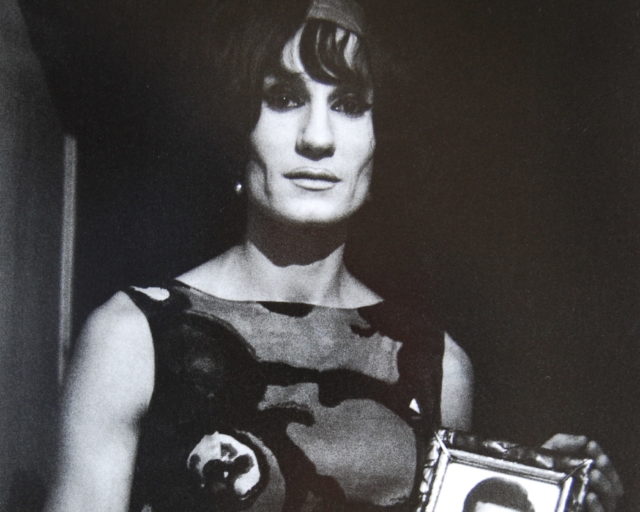

That’s not to say the iconic moments in Resistance don’t need to be seen again and again. These include Syd Shelton documenting pop culture powerfully kicking back against the rise of the far right in Britain at the 1978 Rock Against Racism carnival, and Christine Spengler’s striking portrait of a young girl in Belfast at an IRA funeral procession. As Gilroy reminds us in the accompanying publication, “Unequal access to historical knowledge combines with growing political illiteracy and disengagement. Together, they promote a weakening of imagination that incubates the loss of hope.” Yet, instead of stirring the imagination, Resistance offered mostly familiar tropes of the past.

There seems to be a certain nostalgia for monochrome in political photography, perhaps stretching back to Robert Capa’s famous photographs of the D-Day landings and further entrenched by the iconic images of the struggle for Civil Rights. Of the hundreds of images included in the exhibition, it is astonishing that not a single photograph appeared in color. The fastest film stock for photographers in the revolutionary postwar period was black and white, but the curatorial selection implied that every ensuing struggle after looked the same. This approach to all subsequent political events—which frames the previous century as spilling into this one—risks aestheticizing and antiquating political struggle. Even the show’s typeface called to mind postwar propaganda posters and 1960s espionage movies. If a documentary is made of Resistance, I could predict the soundtrack: The Specials, followed by the Clash, and maybe some Bob Marley, accompanied by Ken Burns–style zooms into the photographs.

© Above Ground Studio

For an exhibition that claimed to be timely—and indeed, resistance is as urgent as ever in this era of neoliberal algorithms, resurgent fascism, and growing inequality—there was an odd lack of urgency in its presentation. I’d worried that a show about the fight for justice would seem out of place in a gallery setting, and in the end the show seemed all too comfortable in its surroundings. I saw little correlation between people’s lives today and the historic modes of resistance being represented. There was no attempt to reconcile the familiar aesthetics of protests of the past with the contemporary moment: it was London-centric and “back then,” with not much speaking to what Linton Kwesi Johnson once called “the Lumpen elements”—everyday people who are uninterested in revolutionary politics.

The lack of an imaginative bridge between old and new forms of resistance left the exhibition feeling incomplete. What it needed was curatorial connective tissue to address our current moment, in which dissent feels increasingly ill-equipped to tackle powerful lobbyists with endless money and coercive tech at their disposal. It is striking, too, that there weren’t any curatorial interventions that might have activated these historical moments—the images were hung in the classic white-cube-gallery format, one after the other, horizontally, in simple black frames. How might young women dealing with online misogyny spearheaded by the likes of Andrew Tate draw strength from this show? Or the tired-looking men standing outside McDonald’s with large, boxy Just Eat and Deliveroo backpacks, waiting for their smartphones to tell them what the next order is? Or the working class men and women of Margate I saw populating the area around the Turner Contemporary? Resistance clings to older, more familiar methods of resistance set against older, more familiar forms oppression.

© Bishopsgate Institute

© Keith Pattison

Such pictorial disjunction between past depictions and current problems in a neoliberal age is something the French writer and publisher François Maspero noticed in the late ’80s, as he traveled the Parisian banlieue with the photographer Anaïk Frantz to produce their masterpiece Les Passagers du Roissy-Express (1990). In the book, Maspero writes: “The squalor is disappearing and unemployment is rising. Each generation has its own forms of poverty which maybe only the next generation will know how to comprehend . . . poverty for outside exhibition from the golden age of the picturesque (thank you Robert Doisneau) . . . is now only the fate of dropouts, tramps and drifters . . . but how do you photograph all the poverty behind the smooth walls, the silent walls of depression and fear, of all the strains of everyday life, of so much loneliness?” The same could be said of modes of resistance. We live in a moment of unprecedented flux, with such existential crises as artificial intelligence, climate change, and a new, even darker form of capitalism the French economist Arnaud Orain has called “the capitalism of finitude.” Photographs of outraged crowds are no longer enough.

© Henry Grant Collection/London Museum

Even viewed in its own political context, Resistance is a limiting prism. Much was omitted. Early-2000s grime music, which took the crumbs of socioeconomic ruin and created a twenty-first-century version of punk, was vernacular testimony against the gross inequalities of East London. What about early-web hacker culture that fought against the corporatization of the internet, or the tireless work of Doreen Lawrence—mother of Stephen Lawrence, a young Black British man murdered by white youths in a racist attack in 1993—which culminated in a stronger awareness of institutional racism and amplified questions about policing nationwide? Photographs of these moments exist, and they are within the show’s curatorial parameters; they would have offered something other than black-and-white photographs of protest.

A show about resistance could have leapt off the wall, played with high and low culture, and challenged received notions of good taste. As Elaine Brown, the one-time chairwoman of the Black Panther Party, once quipped about the men in the organization, “We didn’t get these brothers from revolutionary heaven.” What was missing in Resistance was naughtiness: the playfulness, subaltern creativity, and energies that refused to bow to the status quo and middle-class etiquette. This was all flattened in the Turner show, and as I wandered through it, I thought of two exhibitions at London’s Somerset House that trod similar terrain—The Horror Show! (2022–23) and Get Up, Stand Up Now (2019), curated by Zak Ové.

Courtesy the artist

Both exhibitions contained ingredients similar to those in Resistance but mashed them up into something new and exciting. The Horror Show! used the figures of the monster, the ghost, and the witch—respectively assigned to the social unrest of the ’70s and ’80s, the haunted ’90s and ’00s (which gave birth to the internet era), and the 2010s (the post-financial crisis years of austerity)—to tell an alternative history of the past five decades in Britain. You came out shocked, disoriented, and charged up. Get Up, Stand Up Now showed resistance in full color, with Afrofuturist sculptures and exuberant footage of the Notting Hill Carnival. Ové described the exhibition as a “place beyond boundaries where we can dare to dream without being limited.” The show was a training ground: It armed its viewers with counterintuitive tricks and cultural technologies that might be applied now. Resistance, by comparison, felt like an echo, an exhibition stuck in the past, looking back at a struggle that has already been lost. Instead of leaving the exhibition buoyed by the energy of resistance, I left with the weight of what felt more like an elegy for it.

Resistance was on view at Turner Contemporary February 22, 2025, to June 1, 2025.