Jason Fulford Can't Be Contained

Jason Fulford, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

When encountering Jason Fulford’s work, just remember, “If you came here to have fun, you will. If not, you won’t.” His photographs and, in particular, his photobooks, are enigmatic, ambiguous, and profound. By embracing these qualities, he has expanded the possibilities for his practice and for the photographic medium. A photographer, publisher, and designer, Fulford has also previously appended his print work and exhibitions with interventions and events.

His new publication, Contains: 3 Books (forthcoming from The Soon Institute in October), offers another opportunity to be open-minded. For the extensively researched book, funded by a Guggenheim Fellowship, Fulford traveled to fifteen countries. Within the publication are three funny, strange, and stimulating volumes—I Am Napoleon, Mild Moderate Severe Profound, and &&—in no particular order. Contains: 3 Books will fascinate and delight, but it won’t answer all of your questions. —Ashley McNelis

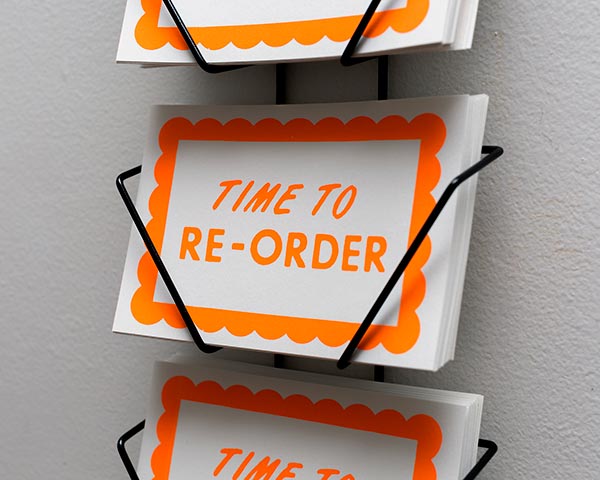

Jason Fulford, Time to Re-Order, 2016. Courtesy the artist

Jason Fulford: I’m glad we’re in Gowanus because after this I need to do some silk-screening two blocks from here.

Ashley McNelis: What are you printing?

Fulford: It’s for a little show down in Philadelphia. I’m making a postcard rack, like the ones you see in a tourist store. It’ll be filled with cards that you can take that say “TIME TO RE-ORDER.”

McNelis: Oh, I like that! Where in Philadelphia?

Fulford: At Crane Art’s Icebox Project Space. Christopher Gianunzio is curating a photography section with pieces by Lucas Blalock, Carmen Winant, Whitney Hubbs, and others, along with several other local curators in one big space.

McNelis. It sounds like a good excuse to take a trip to Philly! Let’s start by talking about literature. The first time I went through Contains: 3 Books, I almost paid more attention to the text than the images. You’ve published several books of your work, designed covers for fiction books, and you’re a big reader. Can you speak to the connection between the image and the word in your work?

Fulford: It’s played out in a lot of different ways over the years, and also in each of these three books. In I Am Napoleon, the texts are excerpts from books I was reading at the time, sequenced into a narrative. The pictures and the words play off each other in an associative way. In &&, the only text is on the cover and in the colophon. It’s a book of single images, so I put a full white spread in between each picture so you wouldn’t naturally think of it as a sequence. Mild Moderate Severe Profound has a caption for each picture, and they are all true stories.

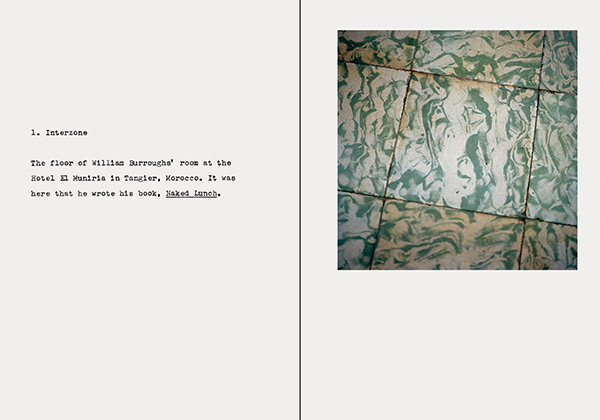

In that book, the captions work in a traditional way, to directly explain the images. I’ve never done that before except in magazine assignments. The texts have a literal connection that adds meaning to the images. For example, take the first picture of the floor tiles in Mild Moderate Severe Profound. It might not have much significance to you, except for maybe it’s graphic quality. But when you find out that William Burroughs stayed in that room when he wrote Naked Lunch (1959), then it means something more. In my book Hotel Oracle (2014), one of main themes is the idea that you can add meaning to places or to objects through storytelling. In this group of three books, I see Mild Moderate Severe Profound as one of the grounding elements. It gives you a clue to what the whole project is about.

Jason Fulford, spread from Mild Moderate Severe Profound, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: Where did you find the inspiration to pair photographs and texts in this manner?

Fulford: One book that may have played a role, subconsciously, is A Forgotten Kingdom by Mike Nelson—the British artist who creates big, realistic-looking installations—for his show at the ICA in London in 2001. He reproduced a dozen or so chapters and excerpts from different books where there was some connection to the theme, and sequenced them to form a new book. It was published on cheap, yellow paper so it felt like a pulp paperback.

When designing a book, I go back and forth between a macro view and a micro view. In Mild Moderate Severe Profound, each spread is an independent unit with text and image, but there is also an overall arc to the book. One big influence in terms of that structure is a book from the nineties by German artist Ute Behrend called Girls, Some Boys and Other Cookies (1996).

McNelis: What else were you reading?

Fulford: I’ve been working on a series of upcoming workshops and re-reading old texts from college like Entropy and Art (1971) by Rudolf Arnheim. I got the same headache I did the first time I read it! It’s so worth it in the end though. He explains two different interpretations of entropy and the second law of thermodynamics. One focuses on the idea of maximum disorder, and the other on equilibrium—that a closed system reaches equilibrium when no other action can happen without an outside force. When I didn’t know if my book The Mushroom Collector (2010) was finished, my friend Stuart said, “You’ll know when it’s ready because it will come to a place where it can’t possibly be anything other than what it is.” It’s the point in editing where everything, like the macro/micro view, locks into place.

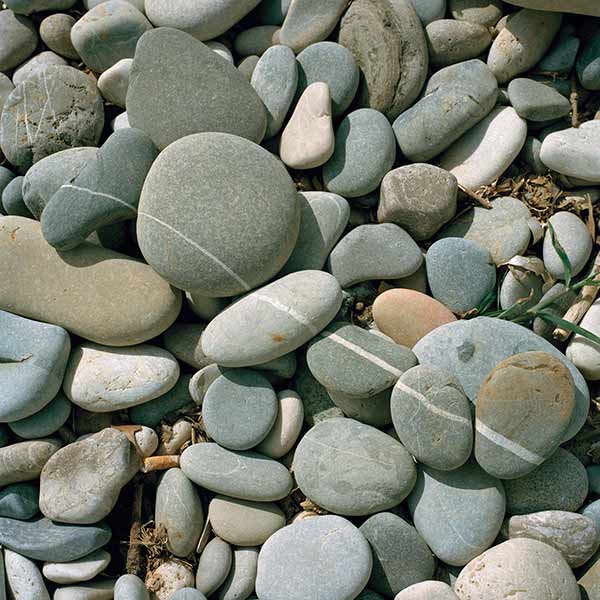

Jason Fulford, image from Mild Moderate Severe Profound, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: I definitely perceived both the individual and overarching elements in the books. I remember you mentioning Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon, ambiguity, mysterious places, and open metaphors. Do you internalize what you find in literature and develop those ideas in your work?

Fulford: Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon were really early influences on me. Books, conversations, films, art, and music all feed into your subconscious. Those ideas affect what and how you see. That’s the best thing about art, I think. If you and I went out and made pictures on this block, we would make very different pictures because we would be looking at different things.

There’s a quote by Goethe that was supposedly found in Edward Hopper’s wallet when he died that I love: “The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me, all things being grasped, related, recreated, molded, and reconstructed in a personal form and original manner.” Think of every person as a filter taking in similar stimuli and then working it through their own life experience before putting it back out there.

McNelis: This would be a good place to transition into talking about ambiguity. You’ve read William Empson, who wrote that ambiguous language makes poetry more interesting. Do you think that that concept of ambiguity can be applied to photography?

Fulford: Yes, and it’s one of my favorite things about photography. When you embrace the fact that pictures are inherently ambiguous, the possibilities open up in terms of using images as language.

I was just down in Atlanta for a week with my mom. I brought a copy of Contains: 3 Books to show her. She admitted that she always wants to be spoon-fed, which is the opposite of anything I usually try and do. We had a good time talking about it. We love each other a lot, but we can be very different.

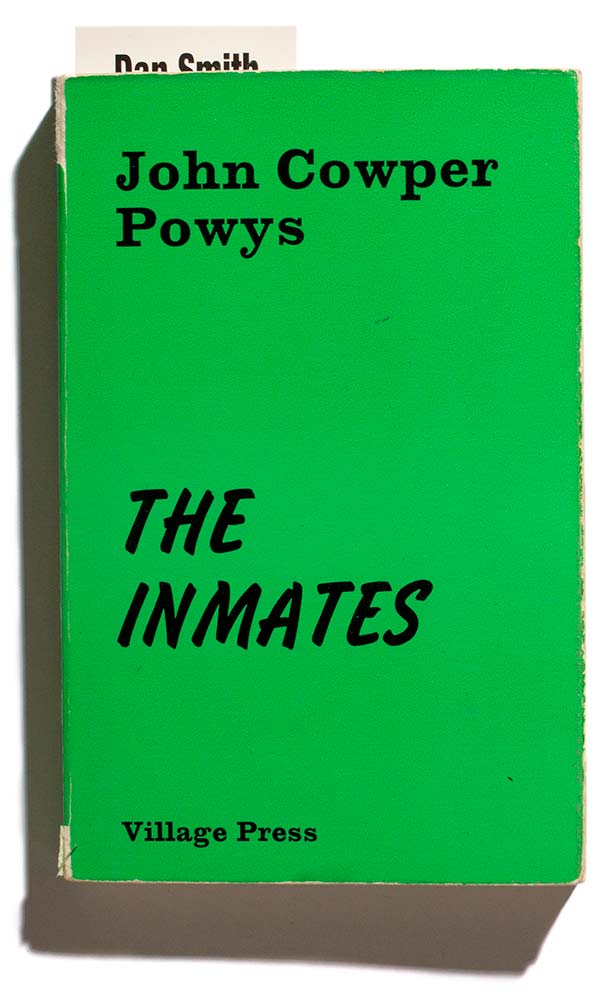

John Cowper Powys, The Inmates, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: That tends to happen with family. The prefatory note in I Am Napoleon—“I think that any book or picture or composition of any sort, once out into the world, so to say, produces a different effect on each person who seriously tries to follow it. I certainly do not think that the author of it has any monopoly in its interpretation”—was a perfectly apt way to begin the project and introduce how you want the reader to approach it.

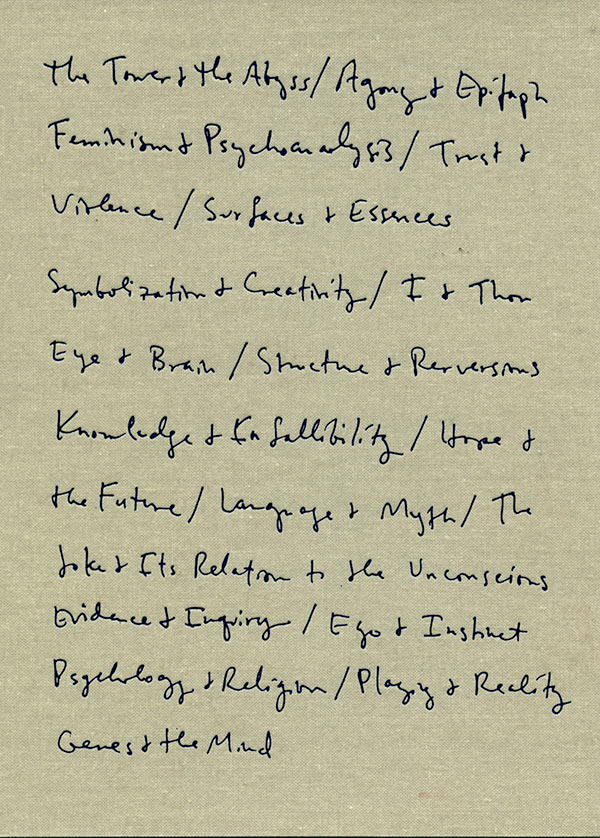

Fulford: It was written by John Cowper Powys in a book called The Inmates (1952). He was a (literally) crazy British writer and mystic that Tod Papageorge recommended to me. He moved to the United States and made a living by impersonating famous writers from history and touring to give lectures as them. He then married a New Yorker and moved upstate to a small town that reminded him of the countryside in England where he grew up. He wrote some of his most famous novels from there. I had an idea with Aaron Schuman, who actually lives in the area where Cowper Powys was from in England, that I would take pictures in upstate New York and he would shoot in England, then we would mix them together and make a book. Somehow it never panned out but we still like to talk about it.

The Inmates had a beautiful green cover with the title written in black in sign painter’s casual font. I bought it for the cover, and later found out that it’s worth reading. It takes place in an insane asylum in England. In the preface he talks about how he’d read a lot of books about insanity and that none of them seemed to acknowledge the humor and the humanity in these places. The story is funny and deep.

McNelis: How did you approach organizing such a large topic?

Fulford: I read a lot of both fiction and non-fiction related to madness over three years and made many notes in the margins. At the same time, I was shooting pictures as I traveled, letting the reading guide my eye. I tried organizing the results in different ways. At one point I literally categorized the pictures as disorders and phobias, and it felt too contrived. A friend gave me a box of psychological tests that are given to children. It contains a lot of little differently sized, spiral-bound books. One is a small book of drawings where there’s one thing wrong in each that you have to identify, like a hand where one finger doesn’t have a nail. At first I wanted to make book that felt like these tests, but it ended up feeling too serious. I wanted my book to feel more open and playful. I hope the reader gets some pleasure from it, rather than feeling like they’ve been lectured to.

Jason Fulford, image from I am Napoleon, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: How do you hope that the viewer will view or interpret Contains: 3 Books?

Fulford: I’m wary of directing the reader too much, especially since a topic like the one these books deals with comes with a lot of preconceptions. I mean we all have some connection to it whether it’s mild or moderate or severe or profound. I ended up focusing on a middle range, somewhere between mild and profound; it’s a range in which there’s a humanity, an imperfection that is potentially valuable. One thing people may think about while reading the books is the subjectivity of the term “madness”—how it changes depending on each person’s culture or peer group. I always say that I don’t want people to think about me when they read these books. You’re going to think about yourself anyway, but I actually want you to think about yourself.

McNelis: It must be challenging to produce a work that’s so open-ended.

Fulford: I’m really comfortable with unanswered questions. I think you have to be game for that to enjoy any of these books. I saw a sign once at a spot where normal laws of gravity don’t apply; strange things like optical illusions happen in areas like that. The sign at the entrance to the spot said, “If you came here to have fun, you will. If not, you won’t.” You have to be open to playing the game to get anything out of it. Otherwise it’s only frustration or cynicism, depending on your personality.

McNelis: I’d be curious to hear more about your photobook practice. I’ve always thought it was very distinct, particularly because of the events and happenings you do for their launches. Do you know the Rosalind Krauss essay, “Sculpture in the Expanding Field,” from 1979? In it, she questions sculpture and discusses its new elasticity. Photography, like sculpture in the mid-twentieth century, has expanded to become a very transitional and fluid medium. Photographs and photobooks can be anything now. The nature of having events—like what you did with The Mushroom Collector and Hotel Oracle—actively sends these objects and ideas out into the world.

Fulford: Those events came about almost by chance, the way one thing leads to the next. It started in collaboration with my editor, Lorenzo de Rita. We wanted to release my books to the world, but we didn’t want to just have normal book parties. We wanted to pick up on ideas in the books, and communicate them in a different way. The events are an excuse for me to use different tools, and they’re fun. I’m also a graphic designer, and I like to build things. The events run parallel to the books and work almost like appendixes. We’ll be planning some for Contains: 3 Books in the fall and winter.

Jason Fulford, cover of &&, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: I can’t wait! Lorenzo’s collective, The Soon Institute, sounds like an incredibly flexible and ambiguous practice. I can’t imagine some of his projects in physical form.

Fulford: Ambiguity defines his life. I love working with him, in part because he always makes sure that everything stays very open until the last possible moment. He’s a bit of a procrastinator, and that’s part of the deal. It’s a good way to make books.

McNelis: Definitely. In addition to working with Lorenzo, you’ve done work with author, illustrator, and designer Tamara Shopsin, and published books with author and illustrator Leanne Shapton through J&L Books. Have you always been open to collaboration?

Fulford: I’ve been lucky to have found great collaborators—where we each bring something that complements the other. When that happens, the final product is always so much better than anything I could have done by myself. And I respect good editors. They each have their own way. Lorenzo, for example, never says, “no.” Instead he just gently suggests—puts ideas into your mind that eat at you until you make a revision. But Tamara will say, “NO,” a lot, and that’s also useful sometimes.

The Photographer’s Playbook (2014) was a big collaboration—not only with Greg Halpern and the staff at Aperture, but with all 307 contributors. Everybody brought totally different things to it. Like a dictionary, it’s a book you can read over the rest of your life. I also love the feeling of kinship that arose from the fact that we all care about photography even though we come at it from our different points of view.

McNelis: Can you talk about your editing process?

Fulford: These days I scan my negatives and edit in InDesign. But I used to work with two sets of contact prints which allowed chance to play a big role. I was just reading about the Jean Arp collages where he would drop cut paper onto paper and glue them down. Or how William Burroughs wrote on multiple sheets of paper and then rearranged them. I work in a similar way, using chance combinations to find unintentional connections between pictures.

McNelis: I read somewhere that you like jazz, which made me think of your sequencing as composing and the individual elements in terms of polyphony and harmony. It’s as though each diptych is a stanza within the whole arrangement.

Fulford: Around the time I made my book Raising Frogs for $$$ (2006), I was listening to and reading a lot about polyphony—from Bach to György Ligeti to African drums—with a little Gestalt theory mixed in. Those ideas transfer well to book design and photo sequencing.

I’ve also been re-reading Alain Robbe-Grillet and Roland Barthes, who both liked to talk in big circles. It’s a fun ride but you often end up in the same place you started. I relate that to a larger philosophy on life where, maybe it’s a cliché idea, but it’s more about the process than the final goal.

Jason Fulford, image from I am Napoleon, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: Whenever I read theory, I’m never looking for just one answer. It’s more of a lens through which to look at everything. There’s too much to contain.

Fulford: Agreed. I grew up with religion, so for me, theory is like church on Sunday—the abstract day where things are talked about as pure ideals, whereas the rest of the week is messy.

McNelis: Speaking of the abstract versus the concrete, one of my favorite images in the book featured the bizarre legends of the Brno Wheel and Dragon.

Fulford: The Brno City Hall entrance is truly surreal. When I was in Brno, there also happened to be a traveling exhibition in town on the topic of Surrealism in graphic design, put together by Rick Poyner. That was the perfect town to have that show.

McNelis: The Czech Republic is kind of surreal. There’s a lot of great art, too. Do you like Fluxus?

Fulford: Yes, though I’ve only learned about it piecemeal. There’s a great library of artist’s books in Chicago called the John Flaxman Library, part of the Art Institute. I spent some time there last year and was able to see a lot of incredible Fluxus originals.

Jason Fulford, image from Mild Moderate Severe Profound, Contains: 3 Books, 2016. Courtesy The Soon Institute

McNelis: They really loved their happenings. Can you talk about the events you’re planning for the book?

Fulford: I think it’s going to be somehow related to the word “Contains.” The website we made for the book has that word as its structure, with a list of contents to the right of it. I think we’ll keep adding to the list of contents as we plan events. The first one, in New York City on September 16, is actually three simultaneous events—“Contains: 3 Events”—all in the Lower East Side. Each one will have a sort of performance that happens in a loop, so you can go see them all.

The overarching idea is that the book contains the three books, but it also contains other things, like three years of traveling, a Guggenheim fellowship, research, etc. There’s that famous Walt Whitman quote, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” I like it as a reminder to appreciate that you can have multiple views at the same time. Though I’m not sure I would like to have multiple personalities. Did you see the obituary in The New York Times recently for the woman who inspired the 1957 film The Three Faces of Eve? That was an extreme case; there are milder versions of multiple personality disorder that can be inspiring. I think of Martin Kippenberger as having extremes of punk and respectability.

McNelis: How did you come to publish Martin Kippenberger’s biography by his sister?

Fulford: I was a fan of his work, mostly from books. I hadn’t seen much of it in real life. Leanne (the L of the imprint J&L) was in Germany having dinner with her editor and Susanne Kippenberger. At dinner, Leanne sent me a text that Susanne was looking for an English language publisher for the biography of her brother, Martin Kippenberger! I just wrote back, “Let’s do it!” It was happenstance.

McNelis: The publishing company and your practice work very well together. I look forward to seeing what else you publish!

Fulford: Well, on the topic of books, I’m really excited about my next, next book. But I have to try to hold off until I get Contains: 3 Books out into the world!

Ashley McNelis is a writer, curator, and art historian based in New York.

Jason Fulford’s book launch for Contains: 3 Books takes place as three simultaneous happenings on the Lower East Side on Friday, September 16, 2016.