Interviews

Louis Carlos Bernal’s Intimate Portrayals of the Chicano Experience

For Bernal, who worked on the border between the US and Mexico, photography was a potent tool in affirming the value of communities who lacked visibility and agency.

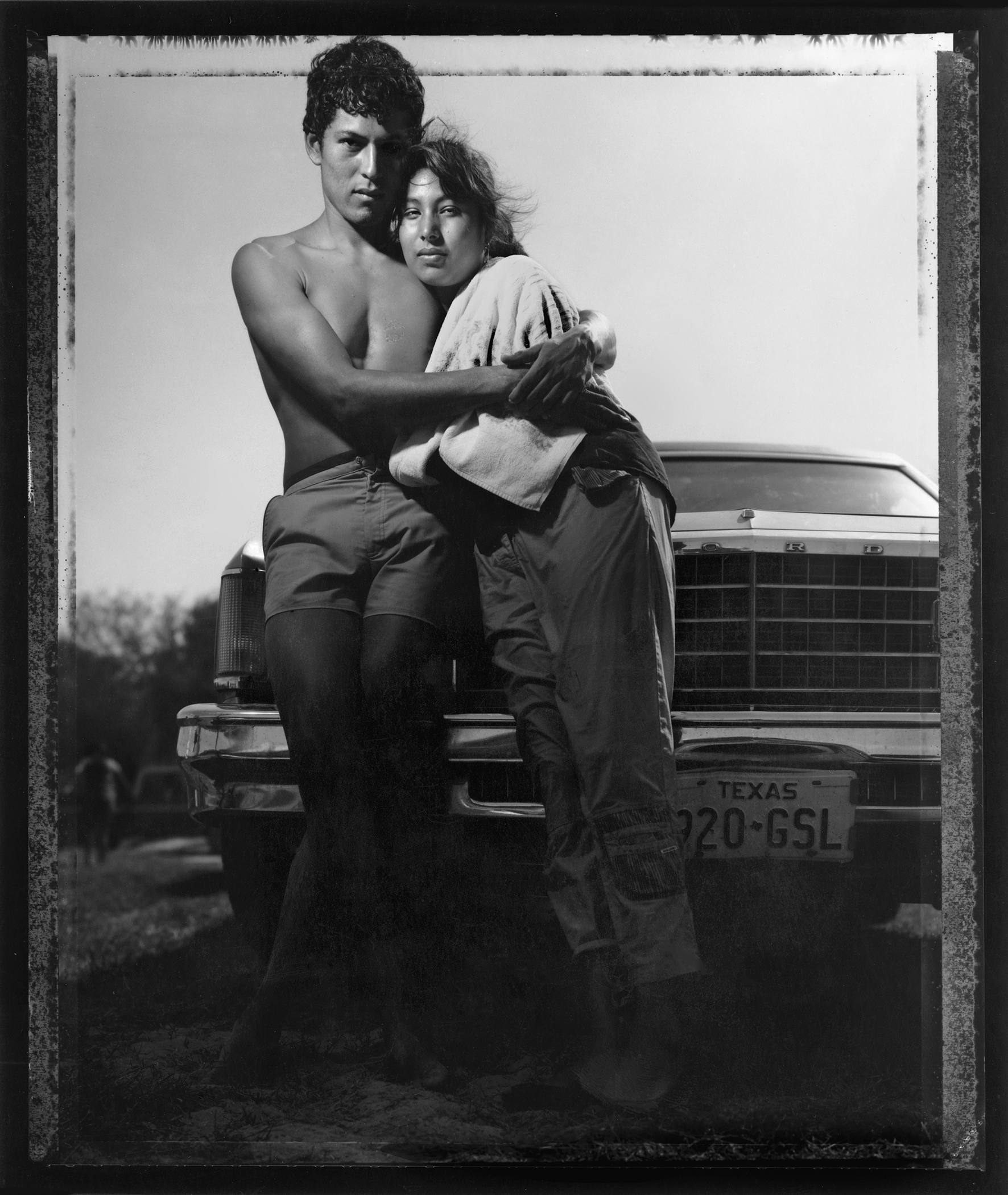

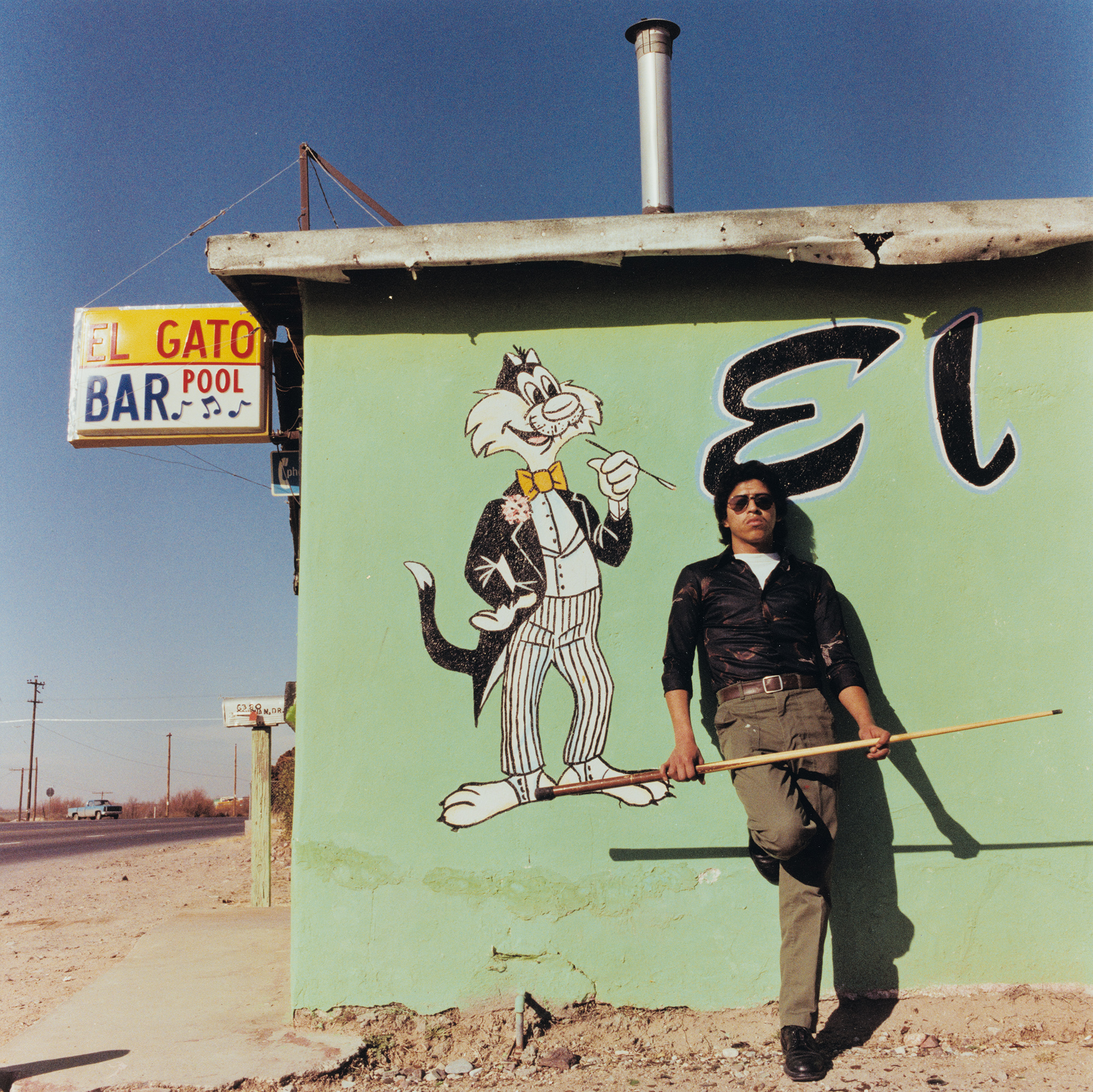

Best known for his intimate portrayals of barrio communities of the Southwest United States, Louis Carlos Bernal made photographs in the 1970s and 1980s that draw upon the resonance of Catholicism, Indigenous beliefs, and popular practices tied to the land. For Bernal, photography was a potent tool in affirming the value of individuals and communities who lacked visibility and agency. “My images convey the spiritual and cultural values of the Chicano experience,” he once said.

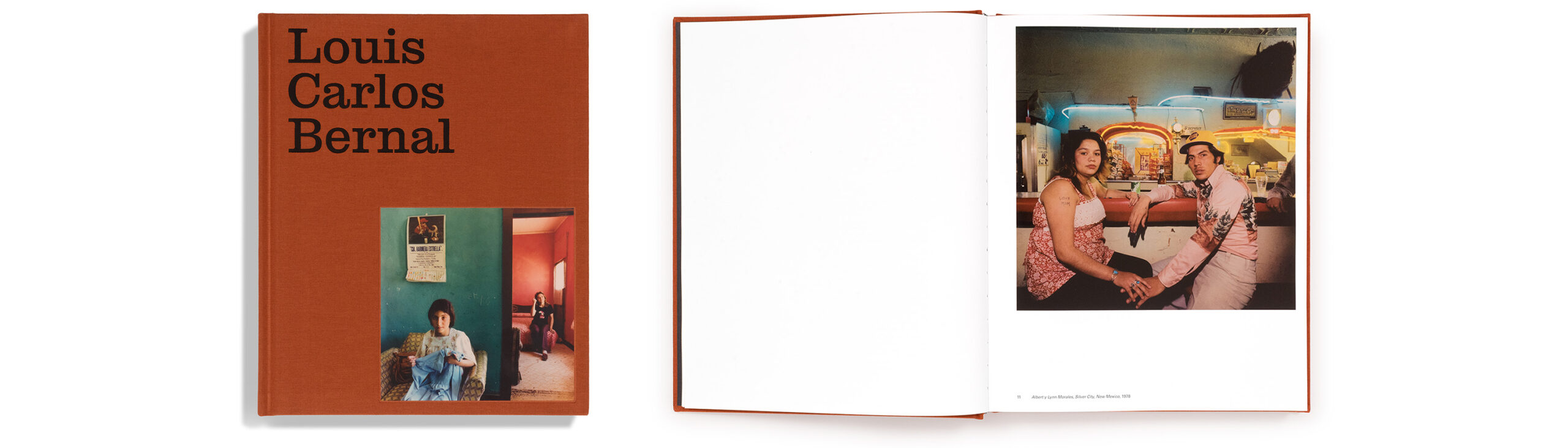

The recent book Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía is copublished by Aperture and the Center for Creative Photography (CCP), coinciding with a solo exhibition curated by Elizabeth Ferrer for CCP at the University of Arizona in Tucson. As Ferrer notes in her expansive essay for the book, “Bringing his full self to his work was Bernal’s longstanding aspiration, and he understood the process of making a photograph as a complex synthesis of the physical and the mechanical, the visual and the psychological.” Working in both black and white and in color, Bernal photographed the interiors of homes and their inhabitants, often presenting his subjects surrounded by the objects they lived with—framed portraits of family members, religious pictures and statuaries, small shrines festooned with flowers, and elements of contemporary popular culture. Bernal viewed these spaces as rich with personal, cultural, and spiritual meaning, and his unforgettable photographs express a vision of la vida cotidiana—everyday life—as a state of grace.

Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía is entirely bilingual in English and Spanish, and includes a detailed chronology of Bernal’s life and work, with images of the photographer as a young man, his exhibition posters, and other never-before-seen documents from his archive. Ferrer, the author of the groundbreaking book Latinx Photography in the United States: A Visual History (2020), recently spoke with Elianna Kan, who translated Monografía into Spanish, about Bernal’s work on the border between the US and Mexico, his pioneering use of color, and why his photographs belong in the canon of American photography.

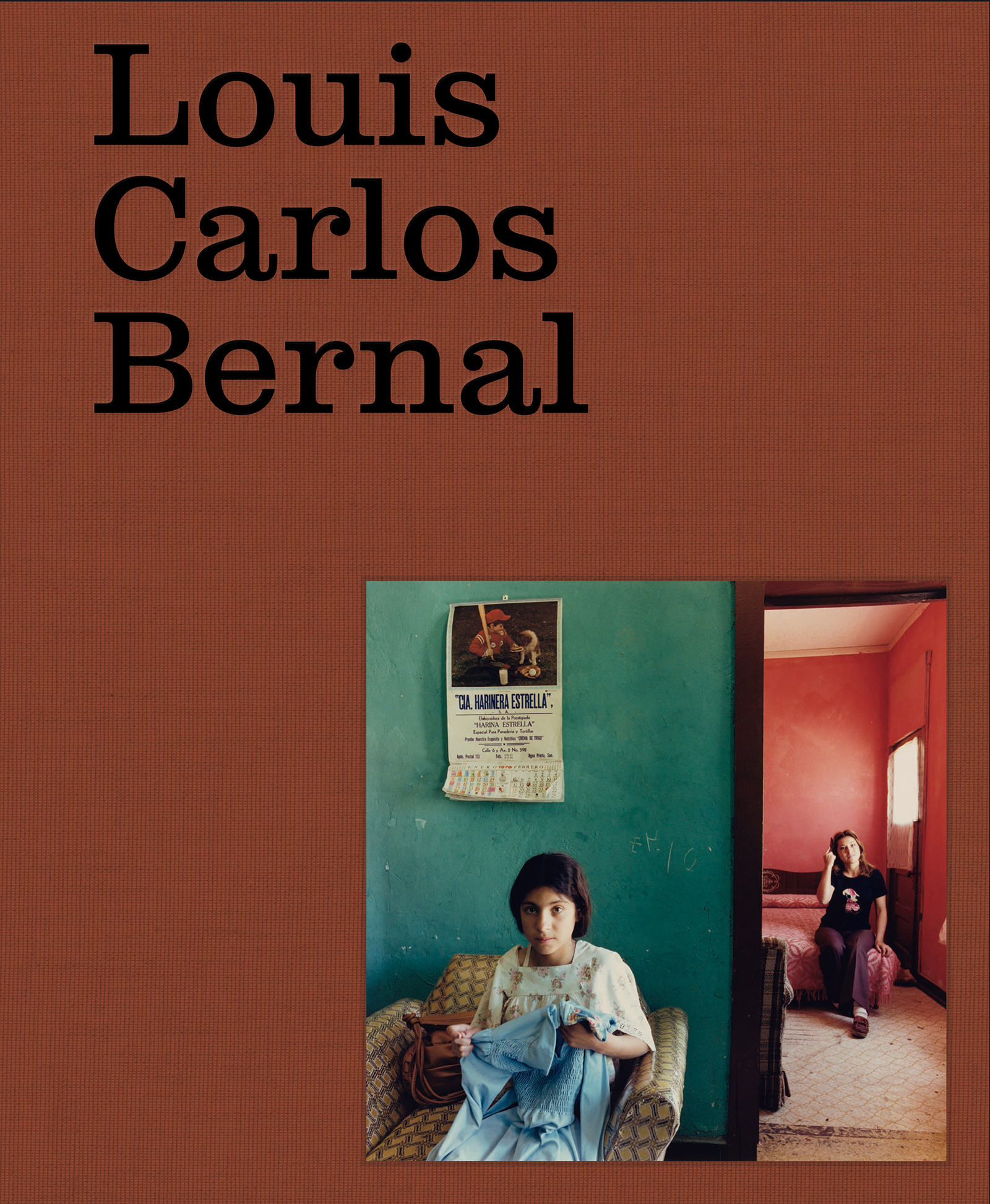

Cover and spread from Louis Carlos Bernal: Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía (Aperture/Center for Creative Photography, 2024)

Elianna Kan: I love this quote that you include in your essay in the book, from a 1984 interview in which Bernal recounts his move to Tucson and the cultural values of the barrios: “During the physical move, I also began a spiritual move back to the barrio and a new attitude toward life—Chicanismo. Mexican-American is the term used to describe a person who is of American birth, but whose cultural soul derives from Mexico. This dual reality has been a burden which has clouded our identity. Chicanismo allows us to accept our history but also gives us a new reality to deal with the present and the future.” This passage speaks to the trajectory of Bernal’s career. In spending all this time with Bernal’s work, how do you see his particular relationship to Chicanismo?

Elizabeth Ferrer: Well, there’s a lot to unpack there. Bernal was born in 1941 in the town of Douglas, Arizona, which is right on the border between Mexico and the United States. When he was a young boy, his parents were poor. His mother was a maid; his father was a boilermaker. They eventually moved to Phoenix where they rose into more of a comfortable working class. They were strivers. They were always very proud of their identity as Mexican Americans. One of the things that the family took great pride in with their children was the ability to speak Spanish. So they were always proud of their culture and in that way, but it was really with Bernal, in the early 1970s, that he begins to see his culture in more contemporary and political terms. When he decided that he wanted to become a photographer, his goal was really to become an artistic photographer, not a photojournalist, not a documentarian.

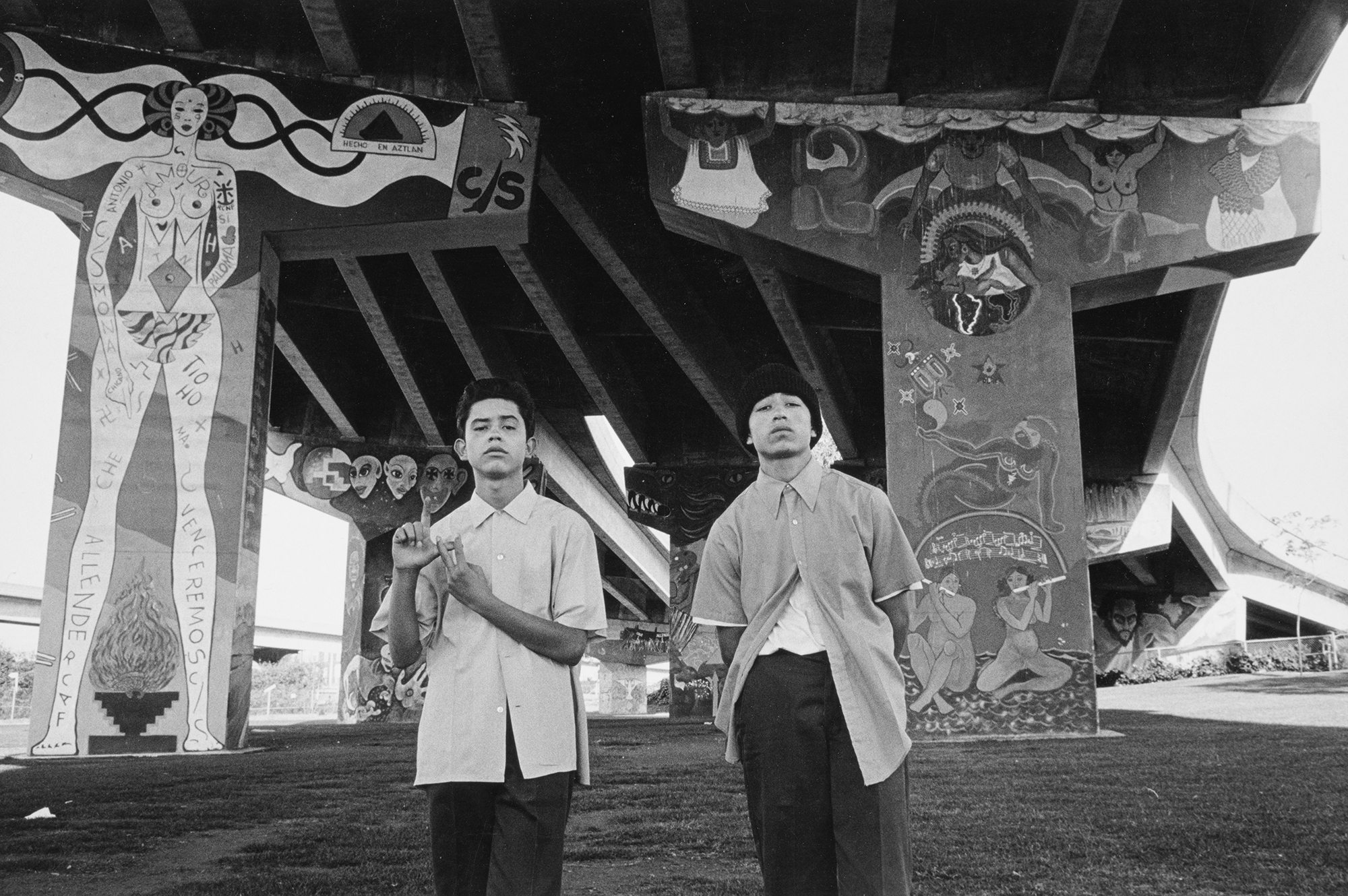

In terms of the Chicano civil rights movement, the photography that he would’ve seen in the early ’70s, when he was in graduate school, was protest photography. Photography made by volunteers for the farmworkers’ movement; photographs of protest, rallies, and demonstrations; and portraits of Cesar Chavez, that kind of thing. But when Bernal was talking about Chicanismo, he was thinking about wanting to express the spiritual core of people. When he was in graduate school, in the early 1970s, he produced some interesting experimental work. This was the time when photography was really breaking out of the box. A lot of young photographers were questioning the ideas of pure photography or so-called straight photography, and he was working with a number of approaches to manipulation, constructing scenes for the camera, working with double exposures.

When Bernal moved to Tucson, he had a realization that he wanted his art to be for the people. And he decided that what he wanted to do, very simply, was to photograph his own people. These were people that were not accustomed to being photographed in this way. In those days, Mexican Americans were often denigrated, and when they were photographed, it was often to show them in an ethnographic or stereotypical way. Bernal wanted to express this sense of spirituality, this dignity, this pride that he had. So he developed his own mode of photography, which, for me, is quietly political. With every photograph that he’s taking of every Mexican American person, he’s making a political statement. He’s saying, Look at this person. This person has dignity. This person should not be overlooked.

Kan: What was Bernal’s relationship to other photographers in the art world?

Ferrer: Bernal was actually quite a good historian of photography. When he went to Pima College in 1972 to launch the photography department there, he taught studio work, he taught darkroom and the history of photography. He also studied with the photographer Frederick Sommer while he was a graduate student. Some of his work actually comes under Sommer’s influence, but that influence is something he eventually had to separate himself from.

Bernal began to use color in his photography around 1978, after he received a commission for a publication and exhibition called Espejo, which was meant to be a broad view of Mexican Americans in the United States. He received a large grant to produce the photographs. He had done some work in color earlier, but it was expensive. He was always very conscious of his limited budget. That project gave him the opportunity to work more consistently in color. There were other people at that time who were working in color as well, like Stephen Shore, who has a reputation as being one of the very first artistic photographers to work in color; before then, color was seen as the province of magazine ads and commercial photography. Bernal was working in color at the same time as Shore was, but he didn’t get recognition for being a pioneer in that way.

Another element of context is Mexican photography. Bernal went to Mexico as early as 1962 in order to improve his Spanish. When he was young, he thought he might become a Spanish teacher. The earliest photograph in the show is from 1962, made during his first trip to Mexico. In the 1980s, he begins to go to Mexico City regularly, and he attends these major colloquiums of Latin American photography that happened at that time. They were watershed events because they brought together, for the first time, photographers from throughout Latin America so they could meet each other. These events created this idea of Latin American photography.

Bernal went to represent the Chicano voice, to be a Mexican American in that midst, to create a bridge between Mexico or Latin America and Mexican Americans in the United States. He met important Mexican photographers including Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Lola Álvarez Bravo. He met his contemporaries, like Graciela Iturbide. If you look at his work made in Mexico in the ’80s, he really seems to come under the spell of Mexican street photography, the focus on Indigenous people, on the urban poor. He works differently always when he travels. He carries his Leica, he works in black and white. This idea of the more posed or intentional image that we see in his interior views in Tucson in the Southwest—he departs from that to work out in the street to photograph. You can certainly see the influence of somebody like Manuel Bravo, who’s often capturing everyday scenes as a means of creating a kind of allegory or to posit a philosophical statement. Bernal does the same thing when he goes to Mexico.

Kan: You mentioned color. That, too, is such an aspect of everyday street life in Mexico. It becomes an essential tool and language, I think, in Bernal’s photography. Can you speak more about the texture and the way that Bernal uses color in his photographs?

Ferrer: Bernal was a master in black and white, a master black-and-white printer. He also taught the zone method. So he understood black and white in a very technical way and in an aesthetic way, but he was attracted to color. I think part of it is just his own community: going into the Tucson barrios and into people’s homes and seeing explosions of colors, bright-pink walls and mismatched upholstery, and also these amazing displays on the walls, home altars with pictures of Jesus and Mary and saints on the walls and dried flowers. He wanted to capture that, but he doesn’t really talk about color in the more stereotypical way that we talk about color when we talk about Latino or Mexican culture.

Bernal wanted to capture what he thought was the spiritual tenor of people, and he thought color brought that out more. Color is not just descriptive; for Bernal, it created a mood. There’s one photo that always stands out for me, Retrato de Boda Rosa (Rosa’s wedding portrait). Bernal photographed an expanse of pink wall; there’s a very small portrait of Rosa in her wedding dress on the wall. It’s almost incidental. I think we get a better sense of how people lived compared to if this photo had been in black and white. Bernal saw color as something psychological.

With every photograph that he’s taking of every Mexican American person, he’s making a political statement. He’s saying, Look at this person. This person has dignity.

And of course, there’s so many fabulous photos that he made that really work with the color, like the photograph Dos Mujeres (Two women), which is on the cover of the book. We see women in two different rooms, and each room has a different color. Bernal really plays off that to create the psychological sense of these women inhabiting these joined but separate spaces. So he became a master of color as well, I think. However, this was an early period for art color photography and the color in a lot of his prints has degraded considerably.

We reprinted some of those images for the exhibition. Digital scans were made from the original negatives, and it is just amazing to see the colors, the way they pop I think that for Bernal, color was a way to go in deeper, to create images in a new way. I think the black-and-white photographs in comparison would’ve seemed like an abstraction of reality to him. With color, he was capturing the layers of these worlds, these small worlds. We’re talking about modest homes and small bedrooms and living rooms.

Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía

30.00

$30.00Add to cart

Kan: I’m interested in those intimate spaces and, specifically, this meta narrative that you draw attention to in your essay on the significance of photography in these homes.

Ferrer: Early on, when Bernal departed from the more experimental work, he often worked with his daughters or with family members. He was beginning to photograph people in their spaces. He decided to venture out into the barrios—Tucson is well known for these neighborhoods that are all close to the center of the city. The oldest barrios, at least at that time, had homes that dated to when Arizona was still part of Mexico. They’re very powerful expressions of Mexican American identity.

Bernal began to wander with his camera. He was gregarious. He knew how to strike up a conversation with these people. He once noted that he was amazed by how easily people would allow him into their homes. Not only would they allow him into their homes, they allowed him into their bedrooms. That gives us some indication of the warmth of Bernal’s warmth and ability to connect with people.

You can get an indication of how he worked from his contact sheets. He worked pretty quickly. He went inside a home sized up what he saw. He would sometimes open doors, open curtains, close curtains. I don’t think he rearranged rooms, but he needed to make the most out of available light and space. And he got to work. He would often make only a handful of exposures. You can see, for example, hoe he worked with a family group. In one frame you see a mom and dad and a couple kids or something like that. There’d be some exposures where just one person is in the frame and others where two or three people are in the frame, or he’s shifted the angle.

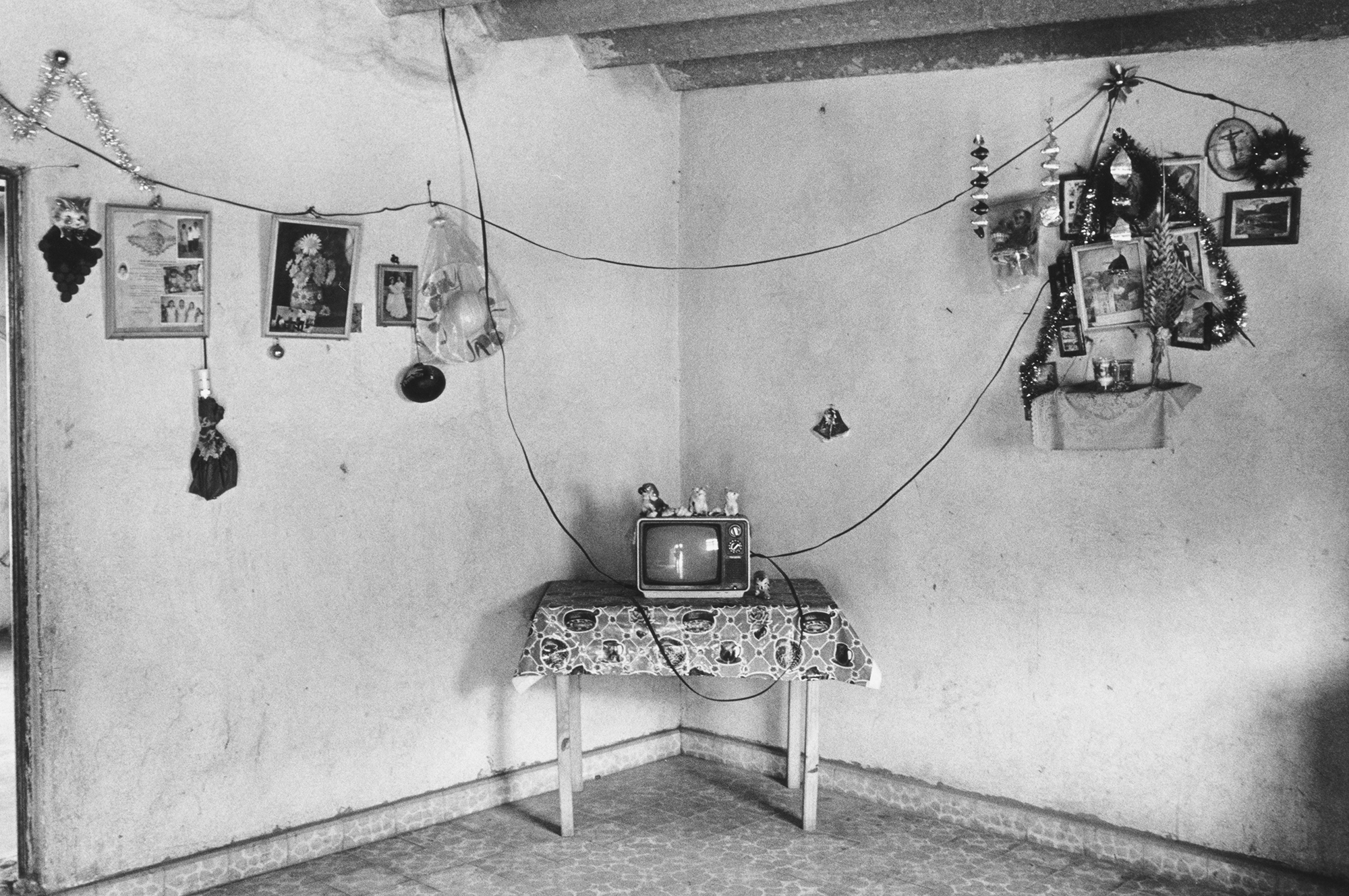

He knew what he’d find inside these homes. He knew he’d see religious objects, home altars, or framed pictures of Jesus or the Virgin Mary. He knows that there are family photos. I think that’s so important because Mexican Americans have always taken great pride in family. When you’re dealing with an immigrant population, the portrait on your wall might be somebody you haven’t been able to see for twenty years, or it might be an ancestor, a prized photo that’s been carried through generations. Those are the elements he uses to frame his own compositions. He frames them in a way to tell us about how these people live, what they value, and again, the spiritual dimension through those objects.

Eventually, Bernal begins to also take photographs of these interior spaces without the people. I think that’s really interesting because these are also portraits, but they’re portraits without faces. They’re portraits with objects. Again, the furnishings, the altars, the kitsch, and these family photos. For me, some of those photographs are the most poignant when you see these bedrooms, very, very modest rooms, with elaborate altars that are heavy with crucifixes and saints. His friend, the photographer Armando Cristeto, told me that he would often get emotional when seeing these displays.

Bernal described himself as a “fallen Catholic.” He went to church as a child, but he didn’t really go to church very often as an adult. But he knew what all this meant, and he knew what this level of faith meant, what this commitment meant, which was common among older Mexican American people at that time. He wanted to capture that, and he knew how to that in a way that lets us know how these people lived, their resilience, their spirit, because they were generally quite poor, and they experienced racism—but they did have their faith, and they expressed it openly in their homes.

Kan: Right. There seemed to be a spiritual wealth which they expressed through the accumulation of ritual objects, or objects of symbolic value, that projected an abundance that was actually lacking in their material lives—in pure dollars and cents terms.

Ferrer: Exactly. These people did not have a lot, but they did these effusive displays of their spiritual lives.

Kan: Your face lights up when you talk about his work at large. Do you have a favorite?

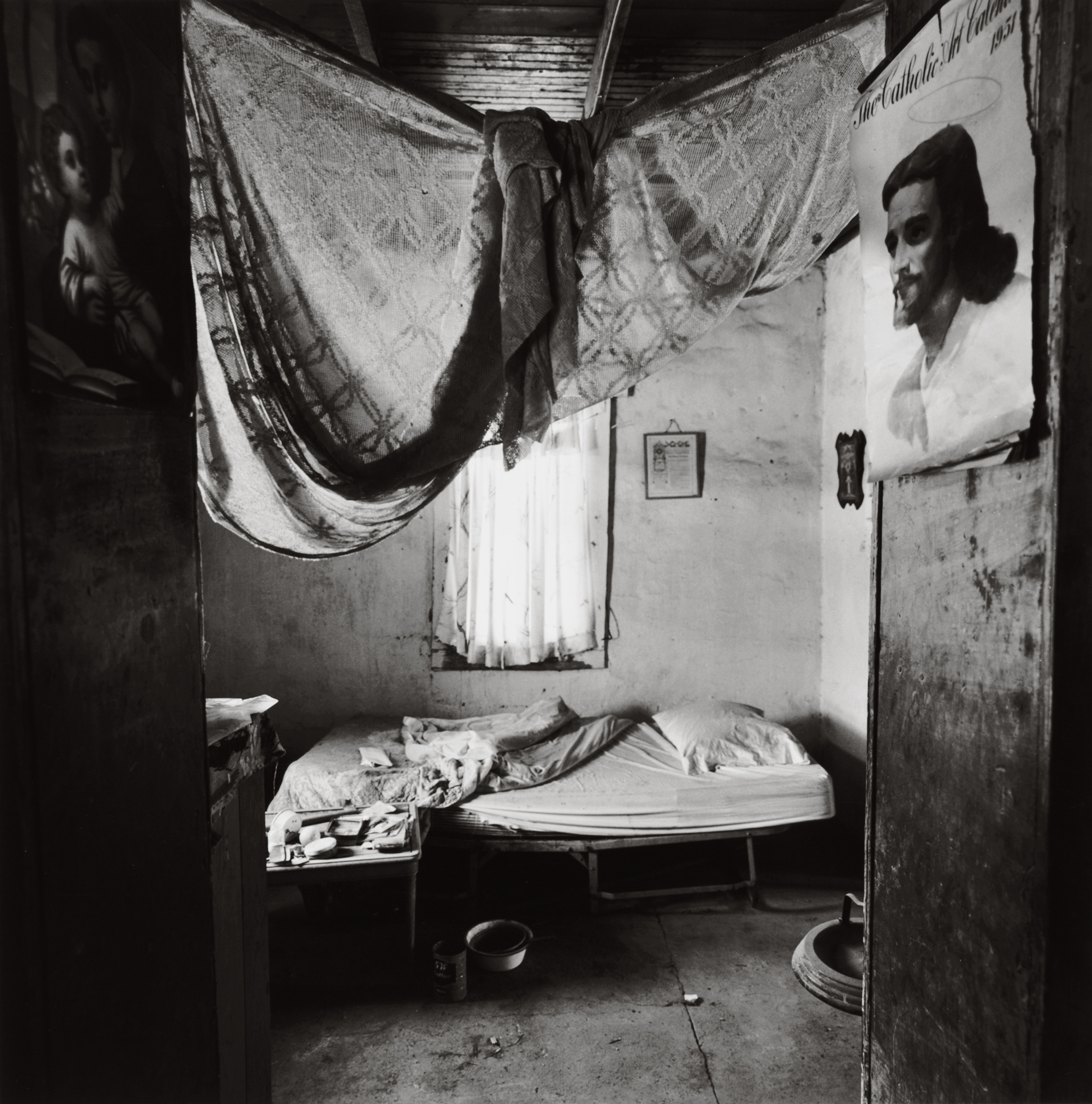

Ferrer: Well, in terms of something that’s haunted me, one thing that we haven’t talked about yet is the Benitez Suite, which he made in 1977. During one of his walks, Bernal encountered this very small, old house, and he knocked on the door, but there was no answer. He noticed that the door was ajar. So he stepped inside, and he realized quickly that it was an abandoned house. Everything was covered with dust. He talks about walking around very slowly and looking and taking it in. He later discovered that the house had belonged to a woman named Mary Benitez—and he managed to meet her.

Mary Benitez was living in a nursing room. She was ill, but she gave him permission to use those photographs. Benitez was a poor, modest woman; were it not for Bernal’s photographs, she would be completely forgotten. With those seven photographs that make up the Benitez Suite, he captures this life. There’s one that depicts a calendar on a wall with an image of Jesus Christ, dating to 1951. It’s hanging on the wall of her bedroom. This is what she would have looked at every day for a quarter century. You feel that her life was precious. She documented her life through notes that were scattered around her house. Bernal carefully arranged them for one photograph; you see her prayers, her grocery lists. It is just so poignant for me to see this life that Bernal depicted for us.

Kan: Were there exhibitions of Bernal’s work in his own lifetime? If so, what was the response of the Chicano community? We can see that on a person-to-person basis, people responded positively to him, letting him into their homes; but what did it mean for these people, if they were able, to see photos of their lives on display for the public?

Ferrer: I don’t know if they did, honestly. In terms of the general reception to his work, it was good. He had a lot of fans in his lifetime but he’s an overlooked photographer outside the Southwest. He belongs in the canon of American photography, a place he very much deserves. But he definitely had his community. He was well-known among Chicano photographers. He traveled a lot. He spent time in LA, and he had a second community there among what was quite a large Chicano art community at that time, in the 1980s. He exhibited his work frequently in Tucson and in Phoenix. He would show his work occasionally in commercial galleries, but more often in university galleries or nonprofit spaces.

Bernal was commissioned in 1984 to create work for the Olympics in Los Angeles. That work was exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. He showed fairly frequently, but I don’t think he sold much work at all. And that was a frustration for him. Going back to his larger context of the photo world, photography was becoming really popular in the late 1970s. Photo galleries were beginning to open up, and more museums were presenting solo shows of photographers. He knew other photographers who were getting this kind of recognition, but Bernal didn’t have these opportunities, the big monographic book or solo museum exhibition.

All photographs © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive

Kan: Finally, what does it mean for Bernal’s work to be shown at this moment in US history? Why now?

Ferrer: It’s a long time coming. Bernal died in 1993, and his two daughters, Lisa and Katrina, decided to donate the archive to the Center for Creative Photography. The whole process of formalizing the donation and organizing and cataloging the materials—all of Bernal’s negatives and prints—took quite a while. The invitation to me to curate the show was in 2021. Aperture was very enthusiastic about co-publishing the book. I think they recognized that Bernal represents a gap in our knowledge of the history of photography.

What’s been interesting to me has been the rise in prominence of Latinx art more generally, which is an area I’ve been involved for many years, with in terms of curating and writing. I wrote a book on the history of Latinx photography more generally that came out in 2021. Bernal is a part of that book, which is the first book on the history of Latinx photography. What I learned is that there is an amazing history that goes almost back to the earliest days of the history of photography.

So, why now? I think because it is high time that we recognize these important Chicano and other Latinx photographers who had been active in the ’70s and ’80s and onward, and who also deserve their place in the history of American photography. I see this as one really, really important step. Bernal, who is often called the father of Chicano photography, deserves to be among the first to receive this major treatment.

Louis Carlos Bernal: Retrospectiva is on view at the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, Arizona, from September 14, 2024 through March 15, 2025.