Ricardo Rangel: Introduction by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

Ricardo Rangel: Introduction by Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

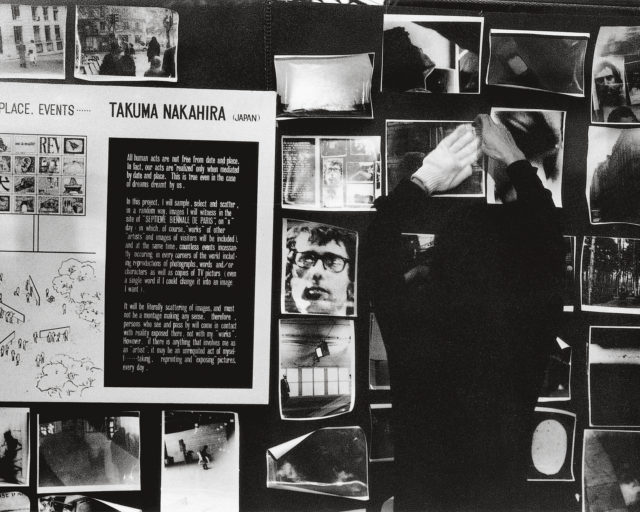

Under the theme of “Photography as you don’t know it,” the Pictures section in the Winter 2013 issue of Aperture magazine presents the work of ten photographers who have been overlooked and undervalued. Among these photographers is Ricardo Rangel. The photograph Sad-eyed model in this street of merry-making, 1962 by Ricardo Rangel is now available for purchase as part of the Aperture limited-edition print program.

Ricardo Rangel, Sad-eyed model in this street of merry-making, 1962. Courtesy Centro de Formação Fotográfica (CDFF), Maputo, Mozambique, and Afronova Gallery, Johannesburg

“Social injustices—I had to denounce them and the most damning denunciation is visual.” —Ricardo Rangel

The Mozambican Ricardo Rangel (1924– 2009) began his photographic life in the 1940s as a darkroom assistant in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo). He joined the newspaper Notícias da Tarde in 1952, at a time when journalists were expected to toe the official line of the Portuguese colonial regime and photographers were regarded as mere illustrators of news. Rangel was the first mixed-race photojournalist at the paper, which gave him access to events and places most white staffers could not photograph. From 1960 to 1964 he was head of photography at the new magazine A Tribuna. Rangel’s wide-ranging images of the harshness of life for ordinary Mozambicans challenged the propaganda of officially sanctioned photography, and suggested a new, oppositional role for the photojournalist.

In the mid-’60s, when the newly formed Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO) intensified its guerilla campaign against the government, Rangel worked in the city of Beira as a news photographer. In 1970, he helped found Tempo, Mozambique’s first color magazine and a new platform for writers and photographers opposed to the regime. During this period, Rangel was targeted by the portuguese secret police and his work was frequently banned. This meant that many of his important images were either destroyed or kept out of the public domain. In 1974, Antonio Salazar’s regime in portugal was overthrown, and FRELIMO gained ground in Mozambique, winning independence in 1975. Two years later, Rangel returned to Notícias da Tarde, then moved on to head the weekly Domingo. In 1981 he co-founded the Associação Moçambicana de Fotografia (Mozambican Association of Photography), and in 1983, the Centro de Formação Fotográfica (Photographic Training Center, or CDFF), which would become an archive and studio for many Mozambican photographers.

Independence in Mozambique meant also that rangel’s work began to be noticed outside of the country. He exhibited at the Bamako Biennale and in other African venues, but also in several european museums. Part of his series on sex workers in Lourenço Marques (published in the 2004 book Our Nightly Bread) was included in the 1996 exhibition In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present at the Guggenheim Museum. In these extraordinary images, made in the 1960s and ’70s, Rangel’s sensitivity to his subject matter and his affection for the city of his birth are clear. In the nightclubs of Lourenço Marques it seemed possible to put aside the constraints of life in a repressive society. Sailors from international vessels docked at the port made their way to clubs like Casablanca and the Ritz, where they mingled with locals, soldiers, and holidaymakers from apartheid South Africa. Experimenting with fast film, Rangel shot without flash in the clubs, unobtrusively making images that would represent a pivotal moment in the history of Mozambique, between the death of colonial rule and the civil war that followed independence. This work cemented rangel’s reputation as the foremost documenter of Mozambican life, demonstrating his formidable aesthetic sensibility and the humanity that underpinned his images.

At the same time, however, the circulation of these powerful images has, to some extent, masked the range and complexity of rangel’s enormous œuvre, most of which is now in the CDFF archive in Maputo. Even the inclusion of his work in important exhibitions like Okwui Enwezor’s 2002 The Short Century and Simon Njami’s 2010 A Useful Dream may be a mixed blessing for photographers like Rangel, since few viewers, except the most dedicated historians and curators, look beyond the exhibited projects. Rangel’s photography was deliberately rooted in his home country—in whose cultural life he played a pivotal role. It is this commitment to a particular place that gives Rangel’s work its emotional depth and its political and human importance.

—

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen is a senior lecturer in creative writing at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and editor of the arts publisher Fourthwall Books.