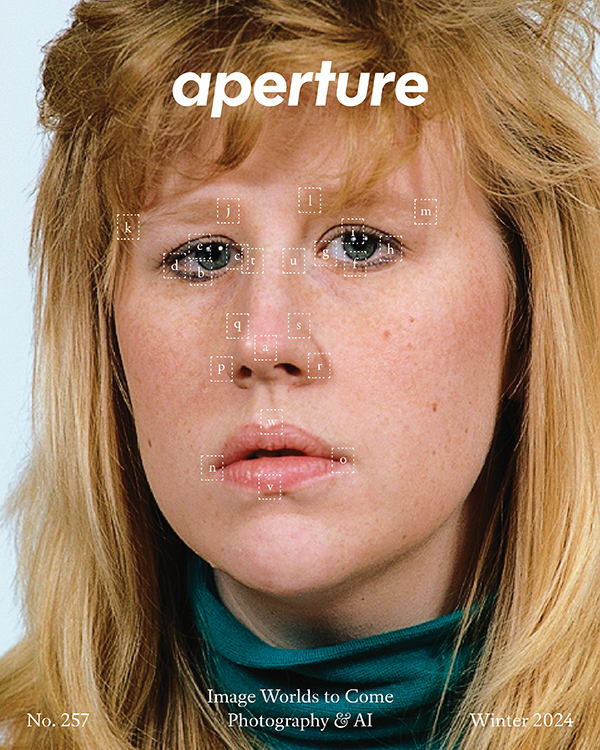

Thank You, and Come Again: Robert Frank in a New York Minute

The legendary photographer’s retrospective is here today, gone tomorrow.

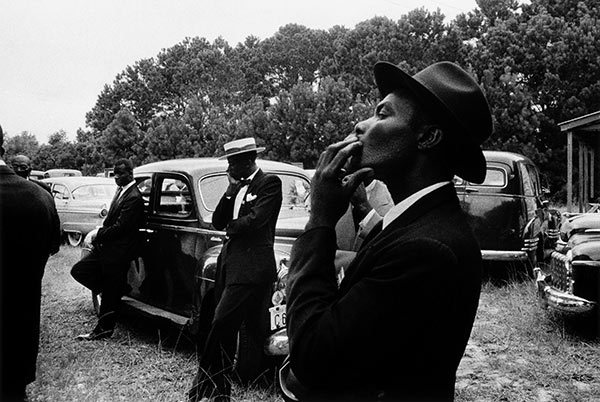

Robert Frank, Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina, from The Americans, 1959 © Robert Frank

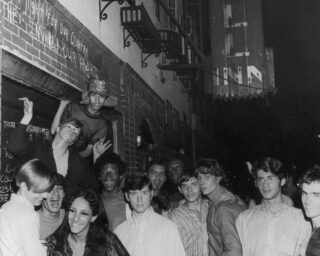

“Don’t you think your gallerist will hate you?” Gerhard Steidl asked his longtime friend and collaborator, the acclaimed photographer Robert Frank, at the recent opening of Robert Frank Books and Films, 1947–2016, currently on view at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. All of Frank’s prints in this show will be destroyed at the end, on February 11, 2016, leaving nothing to be sold afterward. Frank didn’t seem to mind. The exhibition, created by Frank and Steidl Verlag in Germany specifically for academies and universities, presents the entirety of Frank’s photographic and film career on disposable newsprint—an ingenious concept designed to avoid the prohibitively expensive insurance fees that would be attached to edition prints by the ninety-one year old photographer, which command upwards of $600,000 apiece. The freedom afforded by displaying unsigned prints, crinkled from a buzz of students leaning against the prints between classes, allows viewers to finally see the breadth of Frank’s incredible career—rather than a reduced selection of his greatest hits.

Installation view of Robert Frank, Books and Films, 1947–2016, New York University, January 2016

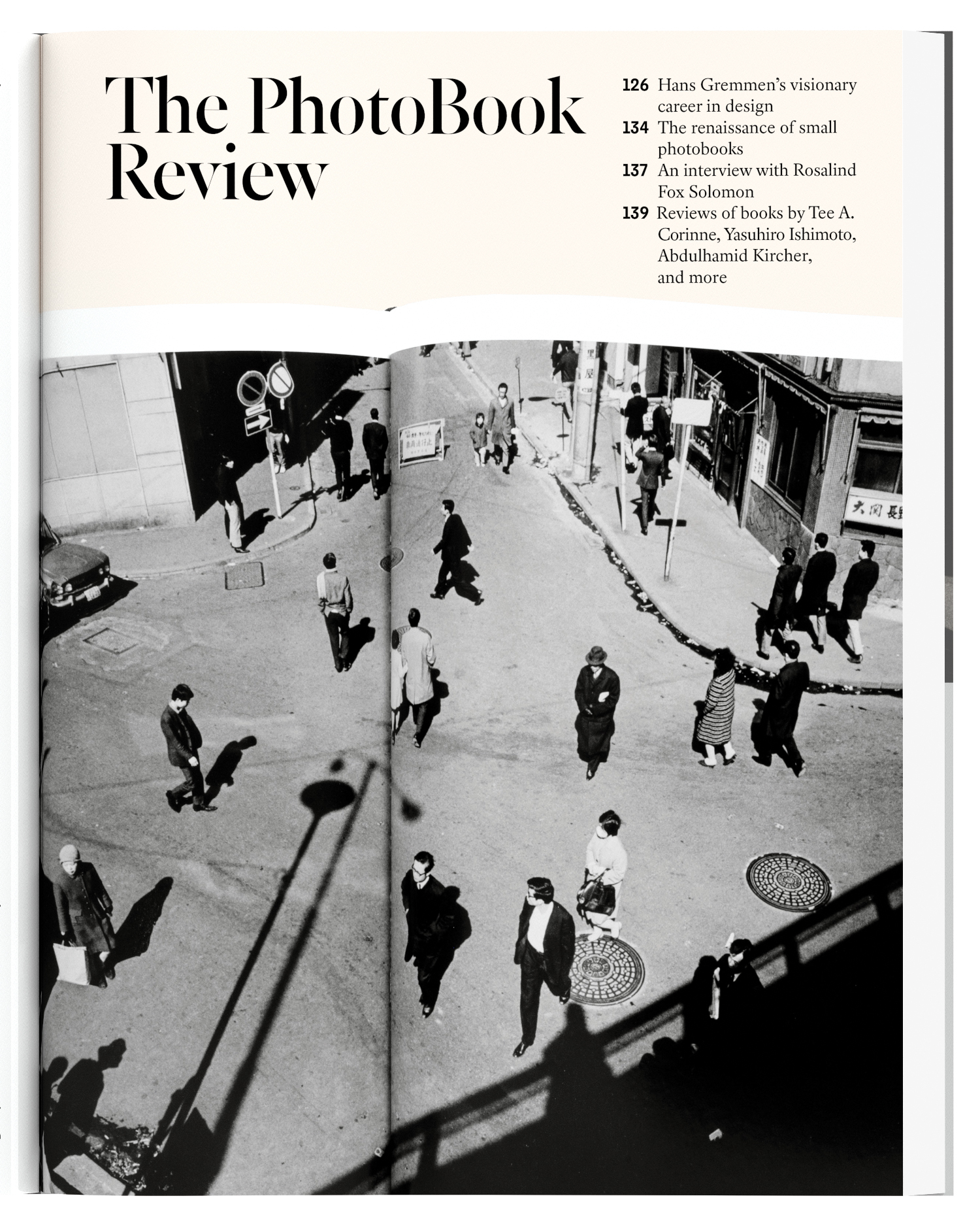

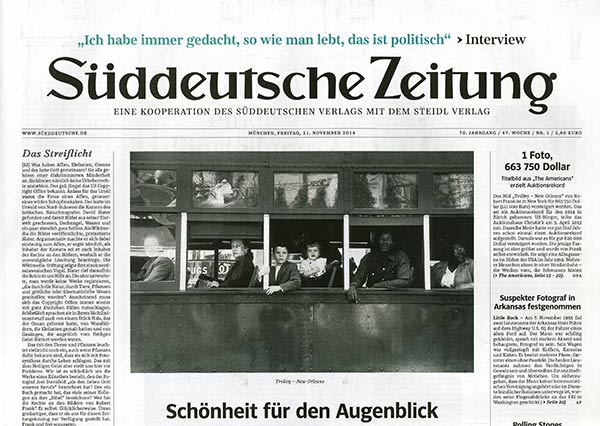

Selections of photographs from each of Frank’s publications are printed on long horizontal sheets of newsprint, while a mobile of his photobooks swings gently from the ceiling. Some of these works are well known; others are obscure collectibles like Zero Mostel Reads a Book (Steidl, 2008). Frank’s legacy goes beyond the material; his work lives on in the minds of photographers and filmmakers everywhere. In producing an exhibition that ostensibly leaves nothing behind for resale value, Frank and Steidl have even extended the highly economical, pop-up concept to the catalogue. Together with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, Steidl produced a special broadsheet for the exhibition in the same format as the German daily newspaper, down to the very last detail including the opening day’s weather and date: January 28, “The forecast: splendid.”

Robert Frank, Books and Films, 1947-2016, Steidl, 2015–16

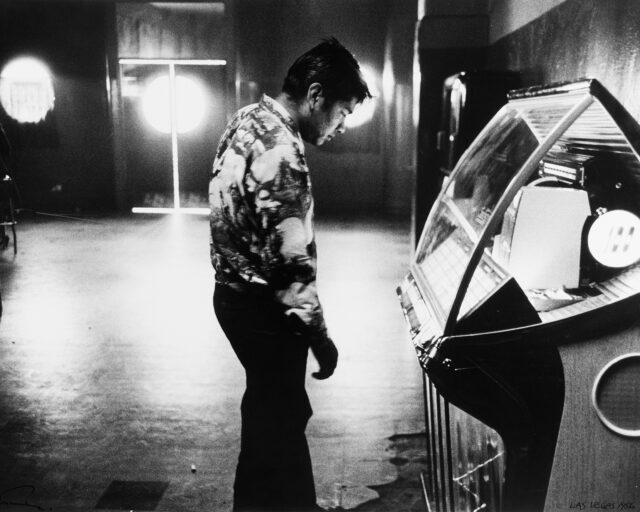

The exhibition affords a rare opportunity to trace the trajectory of Frank’s early empathetic black-and-white documentary images, to his later interweaving of color and black-and-white domestic vignettes. Wall-length contact sheets reveal Frank’s legendary American road trip, complete with grease pencil marks across blown-out frames, question marks, and boxes around the perfect shot. Those now iconic images, filling the pages of the The Americans (Grove Press, 1959), were often a single frame, or one of two at most. In his later Polaroid works, we see his rushed modus operandi turned on himself, as in his two Polaroid self portraits dated September 2001. Mouth agape, glare on his glasses, no presumption—this is the unsentimental Frank after all these years of acclaim untouched by the lure of fame and fortune.

Robert Frank, 2009 Mabou, from the book Household Inventory Record, 2013 © Robert Frank

To the question about whether Steidl’s exhibition would displease his gallery, Frank answered, “I don’t think so. I’m happy to see the photographs live again and to be appreciated.” As if Frank hasn’t done enough for posterity, his latest enterprise is a reminder that all art is ephemeral. “Sometimes the photographs can live longer because it becomes an image that will live longer in people’s minds,” he said, by way of wrapping up his remarks at the opening. “And that probably is the best thing about my photography. So I’m here to say thank you, and come again.”

After closing at New York University, Robert Frank: Books and Films, 1947–2016 will be presented at Bergamot Station, Los Angeles, beginning March 31, 2016.