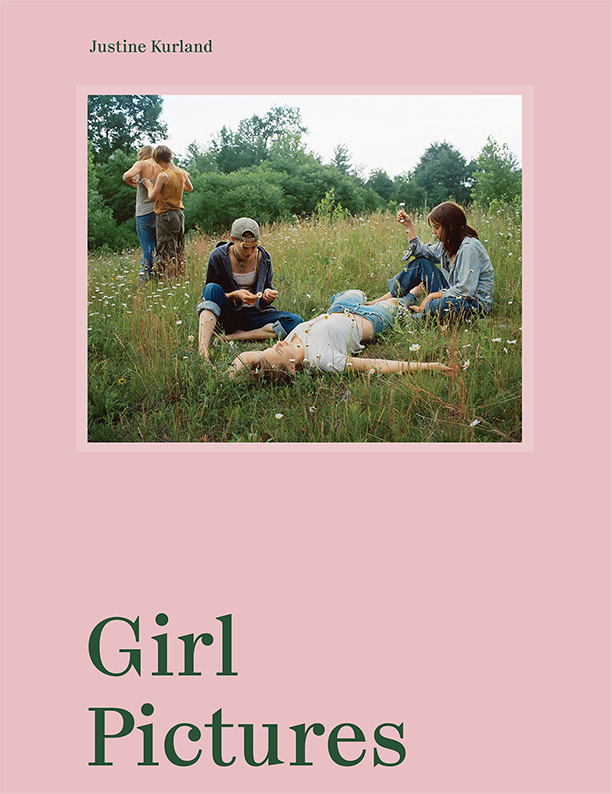

Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures

$50.00

Out of stock

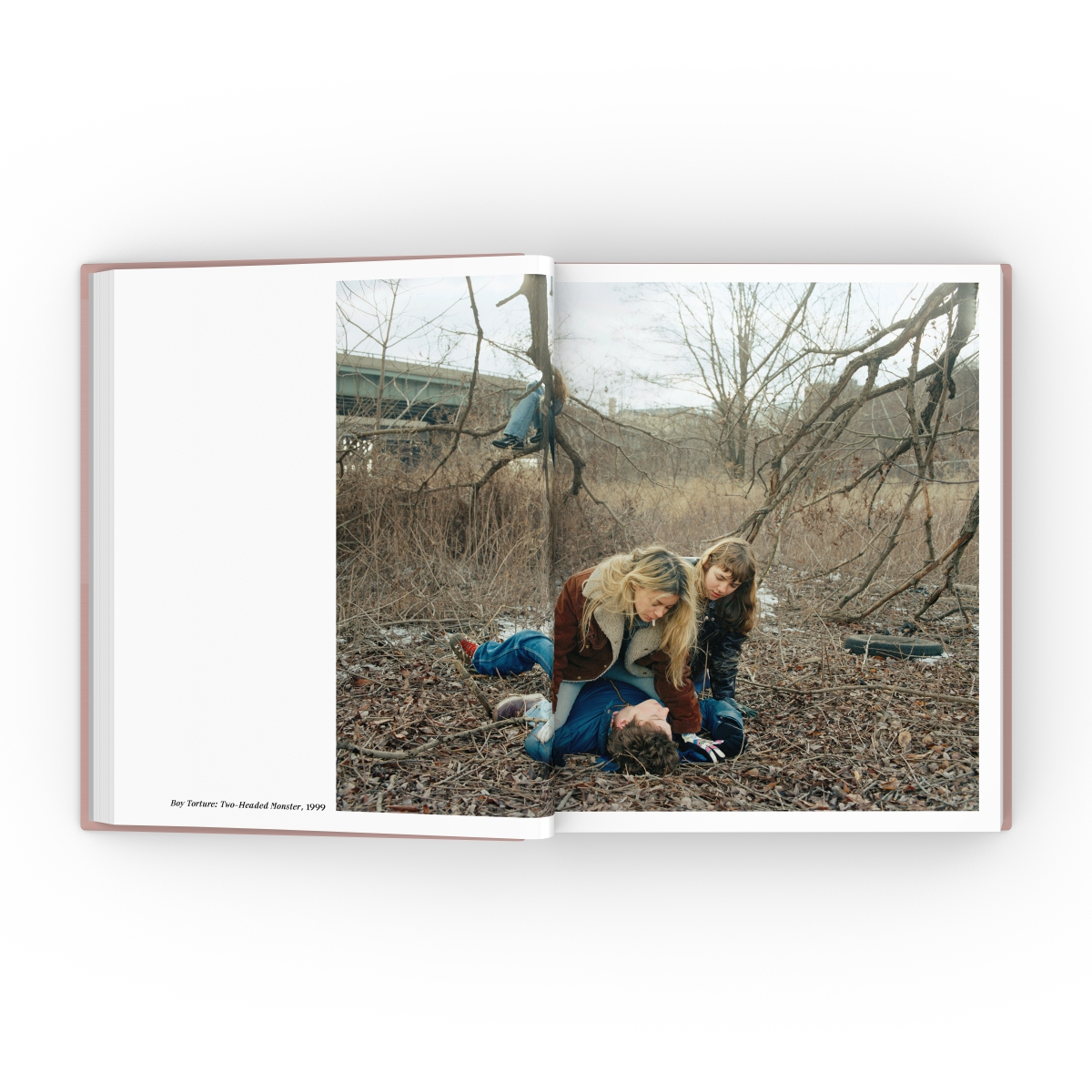

The North American frontier is an enduring symbol of romance, rebellion, escape, and freedom.

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 144

Number of images: 76

Publication date: 2020-05-26

Measurements: 8.8 x 11 x 0.7 inches

ISBN: 9781597114745

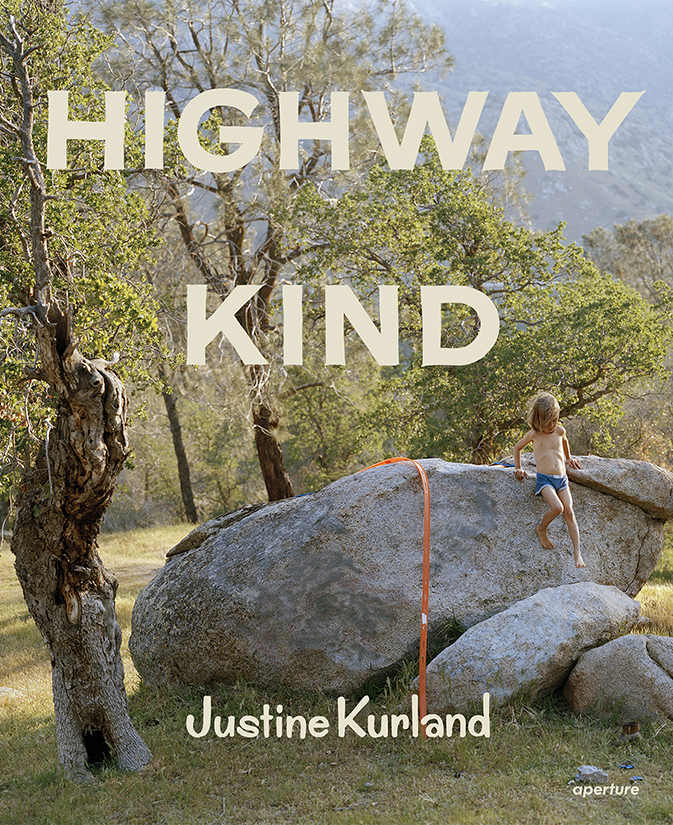

Justine Kurland (born in Warsaw, NY) is a an American fine art photographer, based in New York City. Kurland received a BFA from the School of Visual Arts and an MFA from Yale University. Her work is in the public collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Guggenheim Museum, and International Center of Photography, New York, among other institutions. Her monograph, Highway Kind, was published by Aperture in 2016.

Rebecca Bengal writes short stories, essays, and long-form narrative, frequently about photography. Her work has been published by the New Yorker, Bookforum, Paris Review, Vogue, and the New York Times, among others. She is the Spring 2020 Mina Hohenberg Darden Chair in Creative Writing at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.