Bárbara Wagner: The Maracatu by Agnaldo Farias

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #215 Summer 2014. Subscribe here to read it first, in print or online.

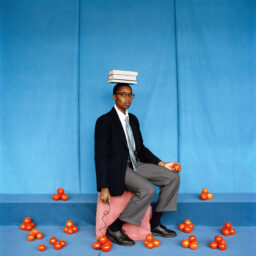

Since the early eighteenth century, Afro-Brazilian performance groups known as Maracatu have descended onto the streets of Recife and other cities in the interior of Brazil’s northeastern state of Pernambuco during Carnival and other festivals. There are two groups: the urban form, the Maracatu nação (nation), devote their dancing and singing—set to the mesmerizing rhythms of the musical style called batuque—to the coronation of the Rei do Congo (King of the Congo). Their rural counterparts, the Maracatu rural, have their origins in the sugarcane mills, an environment with a history of authoritarianism and oppression.

The name Maracatu derives from an amalgam of sources—maracas, the American Indian percussion instrument; catu, which means “beautiful” in the Tupi language; and marã, Tupi for “war” or “confusion.” Their complex background is also evident in the processional standard-bearer of the Maracatu nação, who dresses in the style of Portugal’s Louis XV and is followed by an entourage of ornately styled performers and representations of religious imagery, centering around a dead queen attended by various courtesans. The layered imagery of this ritual performance, which has metamorphosed over centuries, reflects a fusion of African, indigenous, and European elements.

Today, these groups have become seamlessly incorporated into the popular festivities of Pernambuco and involve the participation of all types of people, regardless of racial origin or socioeconomic background, in a nation that still suffers from discrimination and segregation. During Pernambuco’s Carnival, Maracatu groups are distinguished by a unique dance style characterized by formalized frolicking and a subtle choreography of mythic origin related to the dances of the syncretic religion known as Candomblé. Brazilian author Mário de Andrade described this unique dance as follows: “Intoxicated by the percussion, the dancers proceed almost lethargically, slightly reeling on each quarter note, with an almost undetectable trot, and without any visibly formal footwork.” The generally hypnotic nature of a Maracatu procession contrasts with the frenetic rhythm of other dance groups participating in Carnival, most notably the fiercely syncopated Frevo, whose musical style also originated in Pernambuco. The Frevo and the Maracatu reflect a sense of momentary collective elation. For a few days of the year, they don lavish costumes, spend their scant savings to enjoy themselves in the festivities, and parade proudly through the streets of the city. Official government tourist photography often turns to these festivities to highlight the “gold” of Brazilian racial democracy.

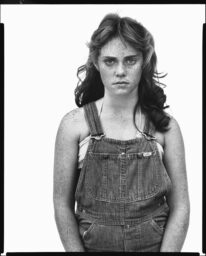

Bárbara Wagner became interested in what lies beneath this false gold veneer and began documenting the dancers’ rehearsals. Her series on the Maracatu offers a portrait of the people who make up the “joyful” faces of this northeastern Brazilian group as they practice their dance. The photographs delve into who the maracatuzeiros actually are when they are not involved in festival performances, and how their days are spent in the run-up to Carnival and afterward. The series looks beyond those brilliantly colored costumes and the atmosphere of celebration flowing almost anarchically through the darkened streets to reveal the dancers as they wait to share their tradition with others for a few moments.

—

Agnaldo Farias is a critic, curator, and professor of architecture and urbanism at the College of the University of São Paulo.