Adventure on the Danube

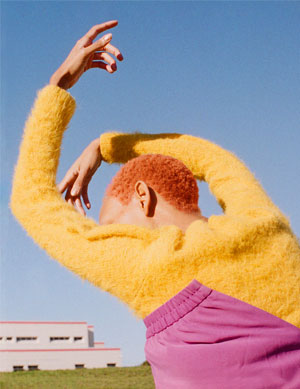

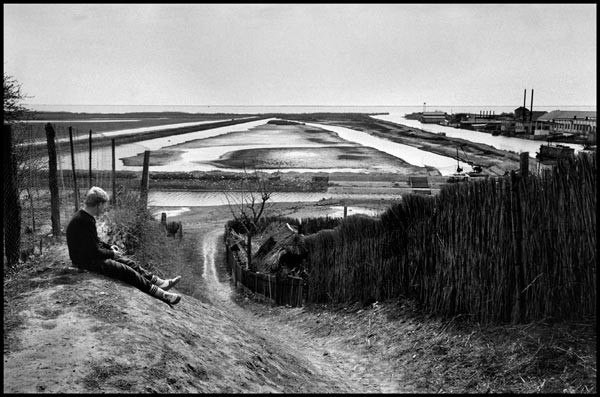

Inge Morath, Oyster farming near Danube delta, Romania, 1994 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

Just before the end of World War II, Inge Morath joined a long caravan of displaced people heading south from Berlin. She hitched rides and spent days and nights walking. “It’s amazing how kind of crusty you get, with dirt and probably bugs,” she recalled. “You can feel nice and ready to drown yourself, and that night there was a little river nice and ready for the purpose.” Saved by a one-legged soldier—perhaps just a phantom—who hauled her off the precipice of a bridge, she continued the slow march to her parents’ home in Salzburg, Austria. It was, perhaps, the first occasion on which a river was to play a decisive part in Morath’s life.

Back in Austria in the late 1940s, Morath made her first journalism contacts by writing for the United States Information Service in Salzburg and Vienna, and later freelanced for Radio Rot-Weiss-Rot and the satirical weekly magazine Der Optimist. In 1951, when she added Heute to her clients, she received a camera as a Christmas present. By then she had become acquainted with a fellow Austrian, Ernst Haas, who had joined Magnum Photos in Paris in 1949. Helping out in the picture agency’s office persuaded her that life was more vivid behind a camera. By 1952, she was working for Simon Guttmann’s legendary Dephot agency in London, where she was as likely to be asked to sweep the floor as to shoot a commission.

Inge Morath, A newly engaged girl, dressed in her Sunday costume and wearing a bridal crown, walks with two girl friends from house to house to announce the great event, Rumania, Near Sibiu, 1958 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

A year later, Morath was back in Paris, working as a researcher and assistant to Henri Cartier-Bresson. Considering her appetite for travel and spirit of adventure, her command of several languages, her burgeoning talent for editorial photography, and her close friendships with several Magnum members, Morath’s admission to the Magnum agency, in 1955, now seems inevitable. Yet, it was immediately clear that she was not going to be the token woman assigned to “soft stories” (animals and children); her first big story was on the worker-priests of Paris, followed by documentations of the London underworld and post-civil-war Spain. Soon her portfolio included Paris Match, Holiday, Saturday Evening Post, and Life, the most sought-after (and highest-paying) of all.

It was the very fluidity of her life—her frequent changes of location, her unbounded work across many media—that would enhance Morath’s fascination with the Danube River. According to the Austrian photographer Kurt Kaindl, Morath “bore within her an inchoate longing for the great cultural spread of Eastern Europe. From the moment she joined Magnum as a photographer, she repeatedly photographed parts of the Danube, especially in her native Austria and in neighboring Germany.” In 1958, as Morath wrote in her travel diary, the time had arrived: “The great adventure can begin.”

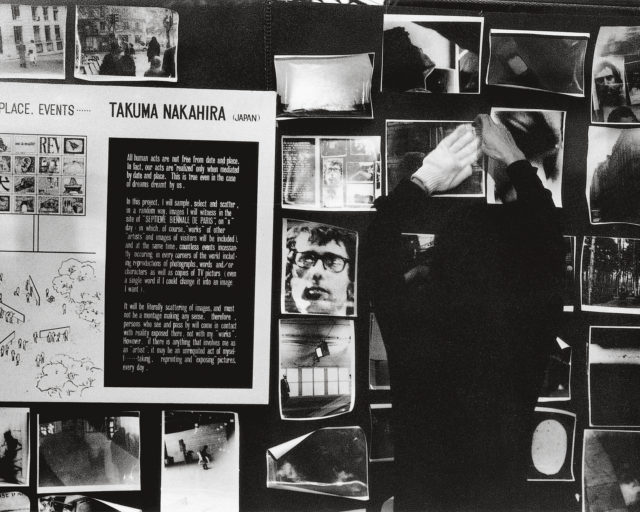

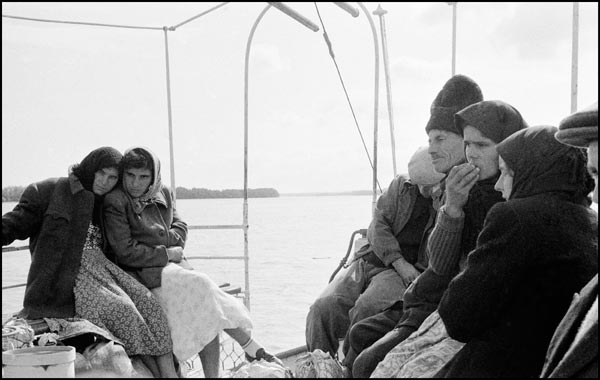

Inge Morath, On board a boat in the Danube, between Galatzi and Tulcea, Romania, 1958 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

The second longest river in Europe, the Danube passes through communities with distinct cultures, languages, and work and life patterns, and has been a source of continuing fascination and inspiration at least since Roman times. Among the many regional inhabitants at the beginning of Morath’s work were Austrians, Bulgarians, Croats, Germans, Hungarians, Jews, Roma, Romanians, Serbs, Swabians, Ukrainians, and the Slovenians of the Morath family’s roots. On May 16, Morath opened her travel journal to write: “Departure from Paris. 21.20 sleeper train to Vienna. Orient Express. Or was it only called Orient Express after Vienna?” Trundling through Hungary to Romania, upon reaching Bucharest, Morath sharply anticipates what lies ahead as soon as she is met by her interpreter: “Roundtrip through town, visit the Village Museum. Bad lunch in Lido. Penelope not a good interpreter. … With this lady I am not going to go far. Courage. We’ll see.”

Courage, however, was an attribute Morath had in spades. Although undefeated, she was frequently frustrated. The journals, typed on an ancient Remington typewriter, are a polyglot mix of English, French, German, and the occasional Romanian, as she records her itinerary, weather reports, and personal commentary. She voyaged, as she wrote, “on foot, drove cars, hitched truck rides, rode trains, ferries, boats and steamers.” In practice it was almost entirely by train or car, the Danube being out of bounds to private travelers, with her program prescribed for her. Irritations, delays, and perplexity were endemic: “From Sinaia to Comarna, co-operative for carpet making. Up to a place called Costa. Great view. But no photos. I am driven crazy by not getting any material. Drive to Brasov, Kronstadt in German. Totally Germanic in aspect. Dinner with a Madame Thalmann. Don’t know why.”

Inge Morath, Liberation Hall, 34 victories in marble, one for each of the German states – from a circle, holding between them 17 tablets inscribed with the names of the battles fought in the victorious War of Liberation against Napoleon from 1813 to 1815, Kelheim, West Germany, 1959 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

Morath had no publication or exhibition planned when she made the Danube journey, nor any anticipated date to resume. Yet two months later, she embarked again on her quest. This time she was more assertive: “I am adamant. Finally obtain permit to sit on one of the tribunes to photograph the parade celebrating victory of Communism. Hot. I still suffer from a kind of isolation.” Exasperated by constant interruptions and requests to show her permit, Morath was a street photographer barred from photographing on the street, continuously reminded of how she was external to the events she witnessed. Hotels are so “grimy” she retires to bed without eating. Banned from accepting an invitation to a wedding party by her minder, casting a sad farewell glance at the delicious food on offer she retires to bed “to eat chocolate.”

Morath’s first voyage on the Danube followed the closing of the Iron Curtain; the last came in the wake of its opening, in 1993. The collapse of the Soviet Union coincided with a proposal from Kurt Kaindl and his wife, Brigitte Blüml, that together they retrace Morath’s tracks along the river. On the first expedition, Morath’s pictures had received their principal exposure in the form of a long photo-essay published in Paris Match in 1959. Kaindl also knew how Morath still longed to pursue her Danubian theme, her lifelong aim to create an extended photo-essay. He assembled the proposal for a book and an exhibition at the new national gallery of photography, the Fotohof, where he and his wife had formed part of a collective of curator-directors. Morath accepted with alacrity, sending a handwritten letter proposing she take a plane from her latest exhibition opening in Pamplona.

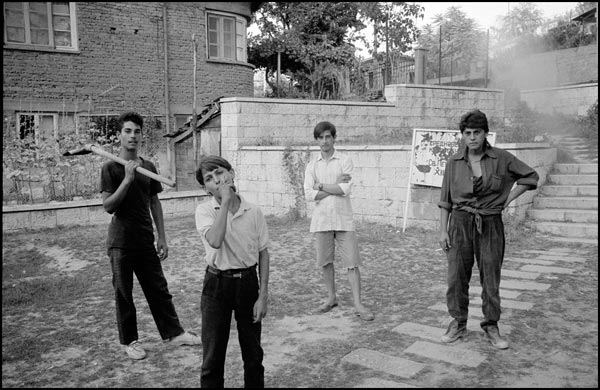

Inge Morath, Boys in the street, Nikopol, Bulgaria, 1994 © The Inge Morath Foundation. Courtesy Magnum Photos

While her first trips were self-financed and made alone when she was in her early thirties, on the later trip Morath was in her seventies. Kaindl and Blüml, managing the project, took turns accompanying her on five trips over two years. They obtained funding and brought the publisher Otto Müller on board; Kaindl proposed a monograph similar to Claudio Magris’s magnum opus, Danube: A Sentimental Journey from the Source to the Black Sea (1986), and was at once accepted. The 1994 voyage, however, was marred by technical problems aboard a boat in the Danube Delta whose ignition kept cutting out as it dodged across shipping lanes, intermittently blocking the traffic and risking being mown down. Fuel shortages persisted, and whole villages banded together to supply enough for transport to the next stopping point. Kaindl’s photographs show Morath aboard yet almost indistinguishable, shrouded in borrowed hats, scarves, and fisherman’s oilskins against the penetrating cold.

Morath liked to point out how a photograph is made in a fraction of a second, yet the image may be the result of years of observation. When the Fotohof opened in Salzburg, in 2012, on the newly named Inge-Morath-Platz, an exhibition showcased Morath photographs. Behind fifty years of creative work was a lifelong yearning: “I secretly long for that stretch of land along the border,” she once said. “When someone asks me ‘Where are you from? Where do you feel at home?’ then—apart from where I’ve lived so long in America—here in these vineyards, my childhood paradise. But the land across the border, about which my mother Titti told me so much, is also a part of it. Strange that I’m rediscovering these things now.”

*This article was updated April 27, 2016.