Japan at the Edge of Reality

Five years after the devastating earthquake and tsunami, a group of visionary Japanese photographers responds to a national tragedy.

Lieko Shiga, Rasen kaigan (Spiral Shore) 45, from the series Rasen kaigan (Spiral Shore), 2012 © Lieko Shiga. Courtesy the artist and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

On March 11, 2011, the world watched as the 3/11 Triple Disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear reactor failure wreaked havoc and destruction across Japan’s northeast Tohoku region. Five years later to the day, Japan Society has opened In the Wake, a group exhibition that examines the various responses by seventeen Japanese photographers to the profound devastation and loss that mark the national tragedy.

In the Wake, conceived by and originally presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has been reinterpreted into three distinct yet overlapping sections in the current installation at Japan Society: documentary approaches to the disaster, response through experimental photographic practices, and the development of a new narrative that blurs the boundaries between the actual events and representations. Intertwined and inescapable within all the photographs, projections, and installations on view are the larger issues of visible destruction and invisible harm.

Naoya Hatakeyama, 2011.5.2 Takata-chō from the series Rikuzentakata, 2011 © Naoya Hatakeyama. Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

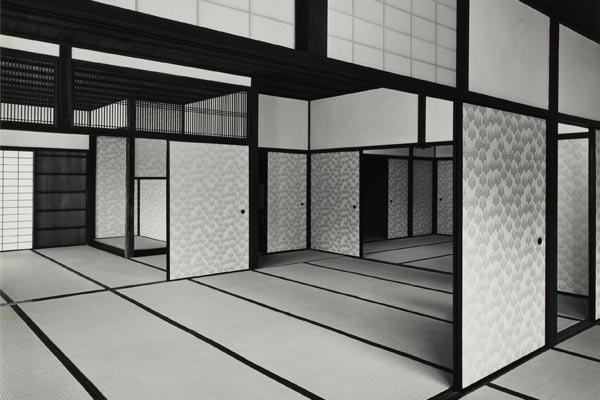

As a photography exhibition about a widely photographed tragedy, In the Wake begins with images and texts by two photographers whose lives and families were directly affected by 3/11 loss. Naoya Hatakeyama, who lost his mother and family house when the tsunami decimated his hometown of Rikuzentakata, presents side-by-side projected images that chronicle the town before and after the devastation, and its slow progression toward recovery. Also directly affected was Lieko Shiga, whose works are prominently displayed at both the beginning and the end of the exhibition. As the resident photographer for the coastal town of Kitakama, Shiga was responsible for photographing local ceremonies and documenting the village’s aging population. Kitakama was hit particularly hard by the tsunami. Shiga’s journal-like text and small-scale black-and-white photographs introduce the magnitude of personal loss immediately following the tragedy. Her efforts to recover family photographs that were scattered by the tsunami are displayed in a large-scale image that shows the village’s assembly hall transformed into a photograph-drying center for retrieved memories.

Takashi Arai, April 26, 2011, Onahama, Iwaki City, Fukushima Prefecture, from the series Mirrors in Our Nights, 2011 © Takashi Arai. Courtesy Photo Gallery International and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Hatakeyama’s and Shiga’s focus on individual loss sets a humanizing tone for the images that follow in the north gallery. Taken by photographers who traveled to the Tohoku region to document the aftermath of 3/11, these photographs convey an overwhelming sense of loss and visible damage from a nonjournalistic stance. Large-format color photographs by Keizo Kitajima show the ghosts of homes and boats barely standing, while a central projection by Rinko Kawauchi sequences images from her Light and Shadow series of two pigeons flying above mountains of debris and a ravaged landscape. The devastation is enormous, but so is humankind’s capacity to recover. Yasusuke Ōta’s photograph Deserted Town, of an ostrich in the middle of an empty shopping street, reveals abandonment tinged with humor.

Yasusuke Ōta, Deserted Town, from the series The Abandoned Animals of Fukushima, 2011 © Yasusuke Ōta. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Not all the photographers who ventured to Tohoku in the weeks after the disaster documented visible representations of destruction. An ominous silence pervades Shimpei Takeda’s abstracted, almost celestial images of irradiated soil. Takashi Homma also exposes unseen dangers in stark funereal photographs of mushrooms with high radiation levels from the forests near the Fukushima nuclear power plant. These nuanced approaches to documenting the invisible contrast strongly with the powerful personal voices and sense of renewal in Lost and Found, a full-wall installation of rescued snapshots from Tohoku debris by the volunteer-run Salvage Memory Project.

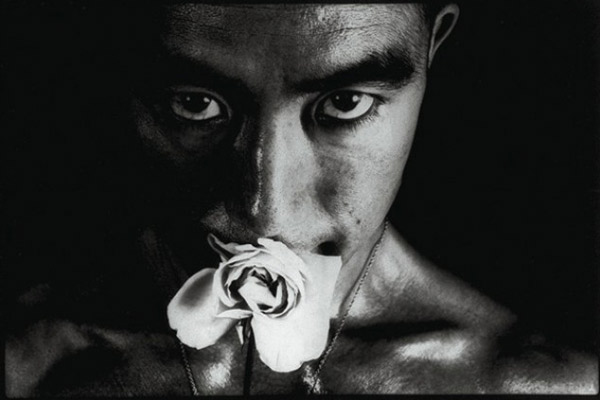

Nobuyoshi Araki, Untitled, from the series Shakyō rōjin nikki (Diary of a Photo Mad Old Man), 2011 © Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A quiet moment for reflection is offered in the all-black gallery containing Takashi Arai’s iridescent daguerreotype images of scenes shot around Fukushima and at Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome monument. Arai’s contemporary interpretations of a nineteenth-century technique form a perfect segue to the south gallery, which showcases photographers whose images rethink established photographic conventions. All of the photographs in this section are by photographers who responded to the 3/11 disaster without traveling to the Tohoku area. Kikuji Kawada—who is well-known for his 1965 photobook Chizu (The Map), a response to the Hiroshima atomic bombing—is represented with a wall of highly saturated, ominously glowing images repurposed from news and television reports. Nobuyoshi Araki underscores the depth of the destruction in his large-scale black-and-white photographs with surfaces defaced by brutal black slashes. Material destruction in a process that combines analog with digital produces the degraded ghostlike images and artifacts in the work of Daisuke Yokota.

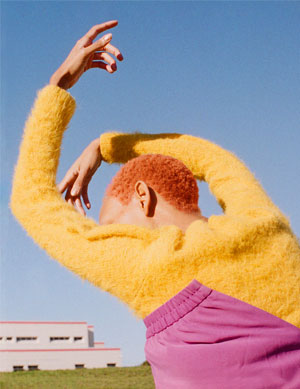

Lieko Shiga, Mother’s Gentle Hands, from the series Rasen kaigan (Spiral Shore), 2009 © Lieko Shiga. Courtesy of the artist and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Drawing upon the Tohoku region’s strong tradition of mysticism, In the Wake concludes with ten large color images by Lieko Shiga of elderly Kitakama residents caught performing mysterious acts against surreal landscapes. Suffused with a garish nighttime glow, their performances are an otherworldly manifestation of reality as it blends with a postapocalyptic fantasy.

For Japanese photographers, history repeats itself. National tragedy and its associated anxiety again act as a catalyst for a new visual language that pushes photographic conventions beyond the edges of reality into a fluid space that hovers somewhere between the unseen and abstraction.

In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11 is on view at Japan Society in New York through June 12, 2016.