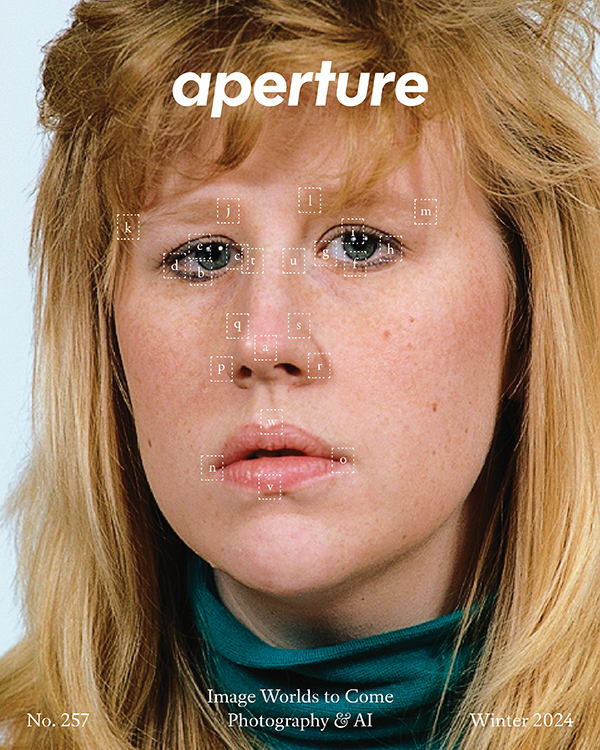

The Loneliness of the Darkroom

.

Dirk Braeckman, E.N.-C.K.-12 – 2013, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Known for his large black and white analog photography of interiors, nudes, landscapes, and otherwise everyday subjects, the Flemish artist Dirk Braeckman doesn’t want his work to be defined by its formal qualities. Rather, the communication between audience and image is central to an artistic practice deeply involved with the material aspects of photography. Through his method and content—and images imbued with a sense of emotional distance—Braeckman criticizes the speed with which photographs are distributed and consumed. In advance of his solo exhibition at the Belgian Pavilion in the 57th Venice Biennale, I spoke with Braeckman about the loneliness of the darkroom, documentary photography, photobooks, and New York.

Dirk Braeckman, 27.1 / 21.7 / 026 / 2014, 2014

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Wilco Versteeg: Your work seems to be grounded in nineteenth-century photographic practices, while the performativity of your images and your engagement with the material aspects of photography seem distinctly of our time.

Dirk Braeckman: The nineteenth century informs my work foremost in a formalistic way. I shoot analog and solely black and white, and I make large, tableaux-like prints on baryta paper, but what I do with this is contemporary. I sometimes teach and some students are interested in the darkroom. I wonder if this interest is sincere, or just a nostalgic reflex. For me, this is how I started thirty-five years ago. These have always been my tools of the trade. The world and the distribution of images has sped up dramatically, but I have continued to make images in the same way. Also, the infinite combinations of Photoshop are dizzying to me. I am happy to work in complete solitude, in the darkroom. I don’t suffer anyone or anything around me while I develop.

Dirk Braeckman, B.O.-D.F.-17, 2017

© the artist and courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: So your work comes into existence in the darkroom, more so than during shooting?

Braeckman: The darkroom is where it all happens, but for me, the taking, developing, printing, and exposing of an image are in fact one and the same thing, separated by quite some time. I do not shoot a lot. Sometimes it takes me months, even years, to print a negative. I want to create a distance between the emotions I experienced when shooting and the final print. I have sworn never to tell anything about the time and place in which my images were made. The story of each image is made by looking at them. Each viewer creates his own story: I don’t tell stories, I just create images. The risk of talking too much about your images is that you destroy their core, you destroy what gives them their strength.

Anyone who looks at my images is free to do with them what they want. It is beyond my control. I only control what happens in the darkroom. I think my images take time to comprehend. What at first seems evident, like a curtain, an interior, or a nude, changes when you take the time to let the image work on you. This communication, rooted in the experience of confrontation with a work, is what finally counts. I try to create works that one can return to repeatedly. Works that are, even if that sounds presumptuous, timeless.

Dirk Braeckman, H.M.-H.P.-11, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: Is it important that this encounter, this experience, happens in a museum, or will a photobook do?

Braeckman: By training I am a painter. At art school, a friend told me I could improve my painting by trying to master photography first. I had never touched a camera before that, but to this day I have never laid it down. However, I still look and experience the artistic process as if I were a painter, that’s why my prints are often so big. Looking at a small print is like looking at a small experience. For this reason, I am not too keen on making photobooks, and I have difficulties showing my work on my website. When you see a reproduction of a photo in a book, you are less likely to think of the actual dimensions of the work. It’s just a print of a photo. In Venice, we have tried to make full use of the space. Space and presentation is everything when viewing my work. My works take the physical space they need.

Dirk Braeckman, P.H.-N.N.-11, 2011

© the artist and courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Versteeg: Your work is often approached formally, but what is your relationship to documentary photography?

Braeckman: Documentary photography interests me because I can’t do it myself. I am too shy for it, perhaps. For a short time when I started out as a photographer I filled in as a photographer for a newspaper and soon found that this was not for me. When on assignment, the journalist needed to remind me to finally take my picture. I was too engaged with the situation to think about shooting. When I travel, it sometimes takes a week before I get my camera out. I need to feel connected to a place before I shoot.

All photography is documentary in a way, if we consider artistic practices as telling of the way we deal with images today. In the 1980s and ’90s, I often spent long stretches of time in New York, a city that continues to fascinate me but for which I have less need now, and Berlin. In these places, I took pictures of everything that surrounded me on the street. For instance, the images I made around the fall of the Berlin Wall were never meant to be documentary, but they have become so over time. The passing of time changed the nature of these works. I never printed them, but I am considering making a book of them. For this project, a book would do.

Work that does not have the pretense to be art but becomes art nonetheless inspires me greatly. This is why Luc Sante’s work on New York crime photography has been so important to me. Especially the images that suggest an event are mesmerizing. A murder scene with the dead body already removed, for instance. In my own work, even if people are present, they are just part of the situation but do not stand out. I never make people pose for me; everything comes into existence organically.

Dirk Braeckman, Z.Z.-T.T.-17 #2, 2017

© the artist and courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

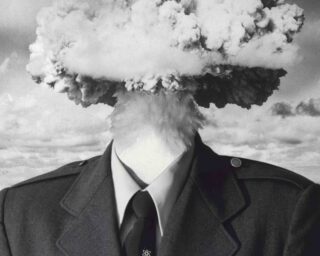

Versteeg: Your photographs are often described as autobiographical, even depressing.

Braeckman: The works are dark, no doubt. Some people ask me if I am depressed, and I tell them, “Yes, I am, but not more so than others.” I am not agonizing in my studio. The dark, existential melancholy qualities of the images attract people. I don’t think my work is depressive. Luc Sante said it very well: To him, my works are like unexploded bombs. There is a certain stillness, a timelessness, but they also are full of energy and tension.

Wilco Versteeg: Do you consider your exhibition at the Venice Biennale a highpoint in your career?

Dirk Braeckman: Yes, at least for now. I don’t know what comes next, but this is a big cherry on the cake. I am nearly sixty years old, but I don’t see this as a retrospective moment. I continue to work and to develop artistically. In Venice, I predominantly exhibit new work, but some older prints as well. My work will be unknown to 90 percent of the visitors, so I hope they will get a clear view of my artistic practice. For those who know me, the new works might shed a different light on what I have made before. Works are never finished, not even when they are printed and exhibited.

Dirk Braeckman represents Flanders at the 57th Venice Biennale, in an exhibition at the Belgian Pavilion, from May 13–November 26, 2017.