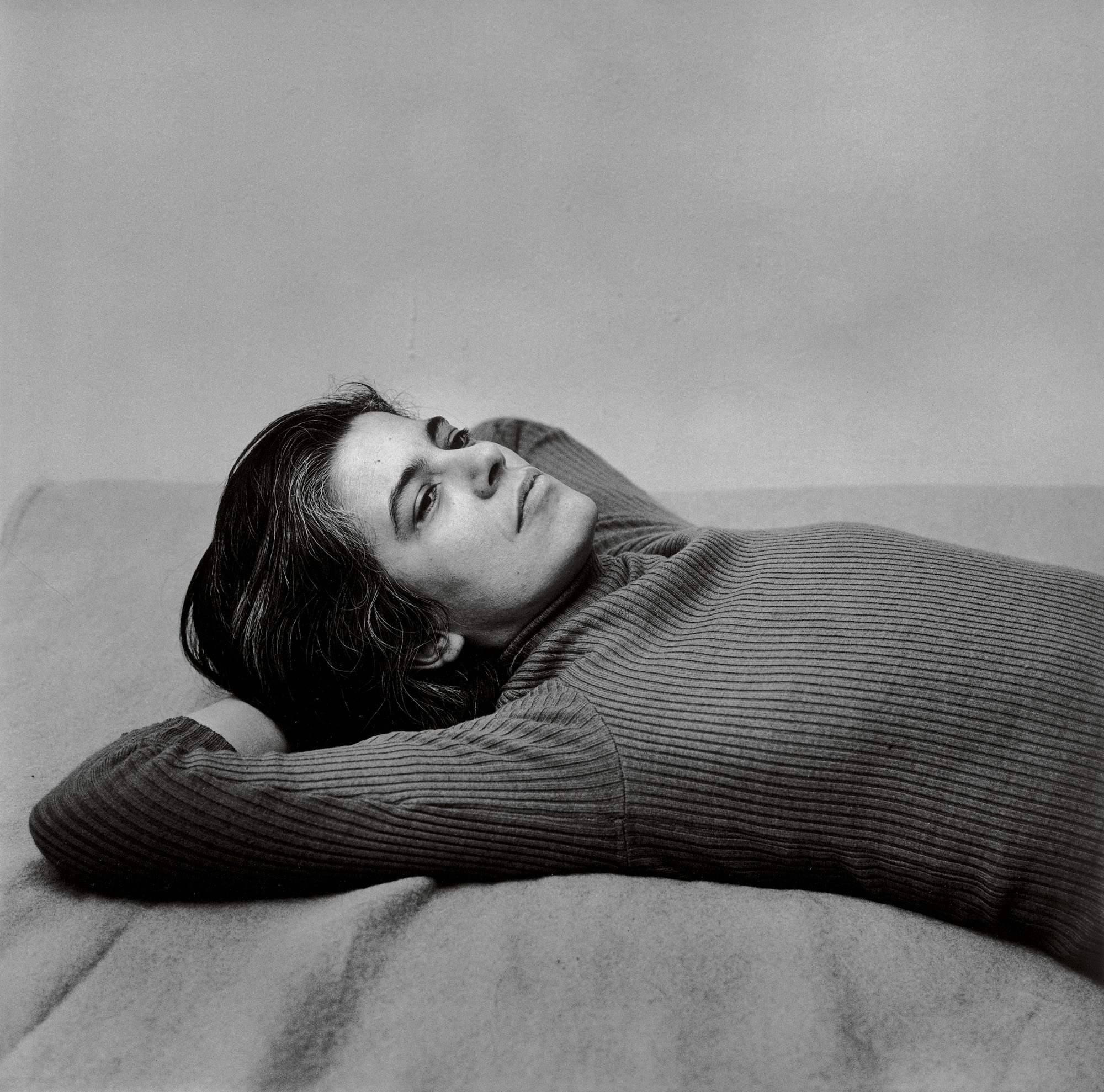

Peter Hujar, Susan Sontag, 1975, from Peter Hujar: Speed of Life (Aperture, 2017)

© The Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

In her 1964 essay “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag wrote, “The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.” Since then, critics and readers have continually asked, Why is it a book? How does it work as a book? and similar queries about artists’ books and photobooks.

Over the past two decades, this inquiry has expanded significantly with the explosion of books about photobooks, and more recently, online coverage of photobooks. While this coverage offers a wealth of information, often including images or videos of the books, most of the treatment tends to be promotional (with commentary more or less amounting to, This is good, I recommend it, here’s a summary) or descriptive, and more about the photographs than the book. Some might as well be reviews of an exhibition containing the images from the book—leaving open the question of how, or if, the work functions differently as a book. Furthermore, because a significant portion of photobook reviews leverage content provided by the publisher and/or the artist, multiple reviews often reflect the same perspective and information, instead of conveying an evaluation of how a particular reader responds and why.

While these reviews are important and helpful, a wider range of writing—namely, critical analysis of the photobook—lacks the same kind of platform. This includes discussion of the choices made not only in the content but in the arrangement of the book itself, as well as other design choices that shape the experience of the reader. This deeper criticism can also more adequately explore the relationship between images and text—how the two come together, how collaboration works, and how they shape or challenge the interpretation of the associated content. Criticism should offer a wide set of voices and opinions, analyze work from different cultural viewpoints, and position the work across a wider historical landscape (including both photographic and other art forms).

This is not to say that all writing must do all these things. But I do argue that a richer diversity of writing needs to be encouraged and supported so it can be made available to audiences who are, or who might be, interested. Without robust critical frameworks and debate—and platforms to support and distribute such writing—the audience of the photobook cannot mature or expand. Other art forms have had centuries, or even millennia, of critical discourse. Mainstream coverage of literature, poetry, music, film, etc. includes reviews as well as more structured criticism, producing a range of judgments supported by objective examination of the work’s detailed elements (for example, Carol Rumens’s poem of the week in The Guardian). The photobook has yet to achieve that level of legitimization and recognition.

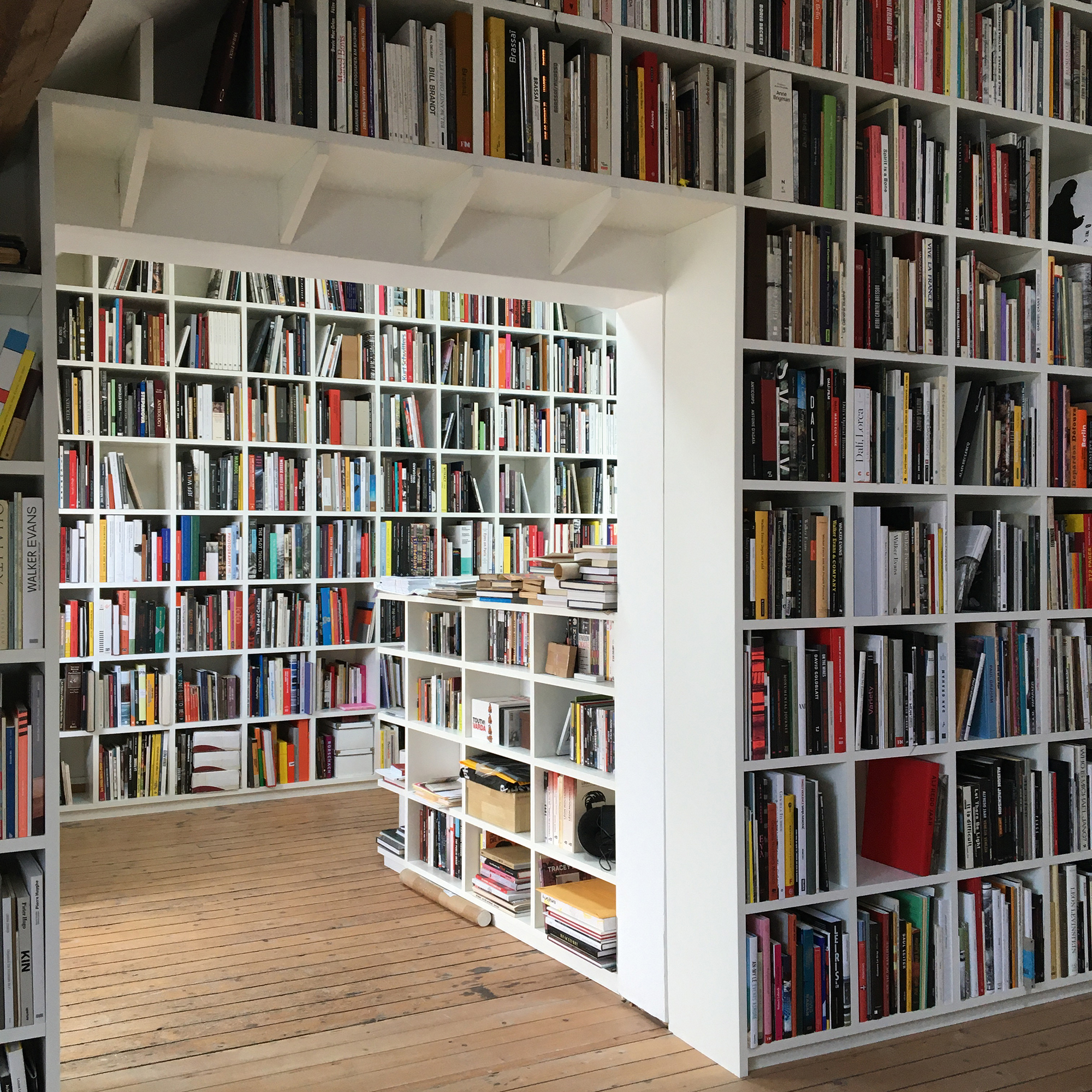

Courtesy Lesley A. Martin

Objectives for Criticism

Richer photobook criticism will serve a range of audiences and objectives above and beyond the advocacy function addressed by many current reviews and lists. Criticism would help to inform readers, and to demystify those photobooks that would otherwise seem totally opaque.

While the current audience for reviews is generally well-versed in the lifecycle of books and the components of their design, there is a wider audience for whom this is a foreign realm. In order to help expand the audience of the photobook, criticism must empower a wider community to pick up a book, see and understand what the makers were trying to do, decide whether they agree with the choices, and assert whether they think it worked and why. That’s very difficult when you don’t know what the menu of possibilities may have been. Without access to the insight that criticism provides, for many readers, the photobook’s medium-specific language is an impediment to opening, let alone enjoying it.

In a related fashion, more robust criticism would also serve as additional feedback (beyond sales and top ten lists) to the artists, designers, and publishers involved in the making of photobooks. An ever wider set of options in dimensions, materials, bindings, inserts, and other features are available, yet there has been limited discussion of how well those choices shape the experience of the book and contribute to the overall success of the work. As with the prior objective, this element of criticism is also oriented around addressing the experience of the reader.

Criticism can also explore in more detail the historical positioning of work—both within an artist’s body of work and across the wider range of photobook history—and contextualize both content and design choices across cultures and time periods. Growing attention around the explicit and implicit signals sent by visual material and design choices like typography and layout in turn requires discussion of these topics as seen in different eras and by different communities and cultures.

Photobook criticism can also engage with a wider set of questions facing the art world, the general book world, and society more broadly. Such topics include:

- the communities (those of the maker[s], subjects, and intended audience) associated with a book and how those connections influence the reception of the work;

- the question of how to extend the dialog across languages and localities, and how to sustain a conversation about work being made locally across the globe;

- whether there are or should be different frameworks for discussing activist, protest, and socially engaged work;

- alternative financial, production, and distribution models;

- zines and related works that may be more ephemeral, or more about working out an idea, experiment, or message

State of the World

Within this landscape of what criticism is or can be, it’s worth looking at where we are and have been over the past twenty years, during which the volume of writing about photobooks has expanded greatly. The primary intent of this essay is not to say that there is a gap—there is and has been excellent criticism of photobooks—but to argue that the coverage remains skewed toward the promotional/advocacy end of the spectrum. There is still much that can be done to both deepen this discourse and widen its reach.

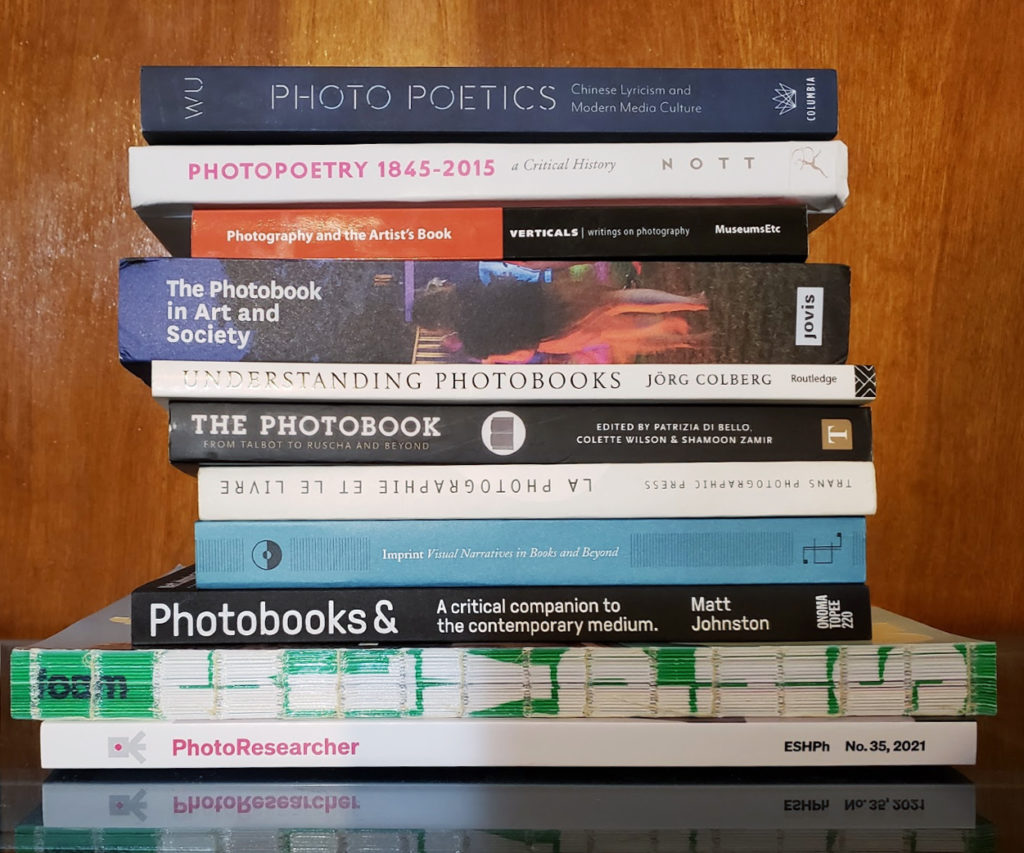

Photobooks are currently shown and discussed in a wide range of forums. As described elsewhere in this issue, books about photobooks have exploded over the course of the last twenty years—from those that provide generalized lists, to those bound by a thematic, regional, or monographic scope. While some provide rigorous analysis (the two Autopsie volumes by Manfred Heiting and Roland Jaeger published by Steidl come to mind), most are in the form of lists of the authors’ choices within the given scope and include merely a description, some background on the work, a focus on the images, and perhaps sequencing. Other elements of book design and experience tend not to get as much attention. The flood of annual “top ten” lists is even more focused on the question of what the selector responded to positively, and most social media posts are also about promoting or recommending the book. Many artists, publishers, and booksellers present their books online, sometimes with discussion or background of the project from a content perspective. Several online review sites have sought to fill some of the gap by providing promotion as well as more extended reviews and in some cases more structured analysis of the books. Several books, often aimed more at makers, have looked at specific elements of photobook design. PBR and other photography-focused journals have also occasionally provided extensive looks at elements of the photobook lifecycle and design process. The most recent issue of PhotoResearcher considered questions of the reception of photobooks in depth.

The world of photobooks overlaps significantly with the broader world of artists’ books (there’s another long-standing debate about the nature and breadth of that relationship). The critical discourse that has been taking place in that sphere over the past fifty years takes up many of the same questions and wrestles with similar challenges. Compared to those of photobooks, reviews of artists’ books often pay more attention to the physicality, materials, and composition of the book as an object, but still primarily maintain a descriptive vs. evaluative standpoint. While the examination of the interplay between image and text in general has a long history, the photograph has only recently entered the fray. Academic study of artists’ books and photobooks from both a practice perspective and an art and book historical perspective is also expanding with research and publications emerging.

A Path Forward?

So what are some suggestions for what we might do?

- Establish and encourage paid platforms for critical writing from diverse, global sources with wide availability. The critical discourse can be in a variety of forms including writing (in print and/or online), live conversation, panels, and video.

- Maintain an online listing of platforms that provides examples for aspiring writers and a guide for those looking to consume such content.

- Create and maintain resources for writers who want to write more expansively about photobooks (understanding process, book design, fact checking, etc.). This should include examples of successful critical writing, resources to help answer questions, and perhaps checklists of issues to consider.

- Develop and support opportunities in photobook-related activities (launches, online discussions, lists, etc.) that include more critical, analytical discussion. In doing so, make the choices and roles associated with the book more visible, and invite critics and other voices to discuss those choices and their impact on the reading experience.

- Create partnerships to enhance translation and distribution solutions to connect artists, writers, and makers globally.

- Cooperate with artists’ book communities, organizations, and initiatives to jointly pursue these objectives and activities.

Some of these are simple and some are in progress to varying degrees. The Book Art Review was launched last year (of which I’m a cofounder with Corina Reynolds and Megan Liberty with the Center for Book Arts in New York) and in February coorganized the Contemporary Artists’ Book Conference to explore these questions. The Photobook Sessions were organized by the Kraszna-Krausz Foundation and Camberwell College of Arts, UAL in May and continued some of these threads with more focus on the photobook.

The objective here is to continue describing and supporting what more can be achieved through a greater range of critical discourse about photobooks, and to encourage both writers and platforms to explore these topics and seek opportunities for collaboration.

This article originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review, Issue 020, under the title “Why Is This a PhotoBook? A Call for a Richer PhotoBook Criticism.”