The Monumental Films of Wang Bing

In his immense documentaries, Wang depicts the lives of Chinese people with intricate and unsparing detail.

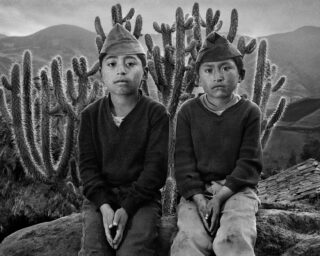

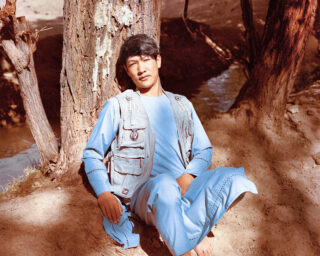

Wang Bing, Still from Father and Sons, 2014

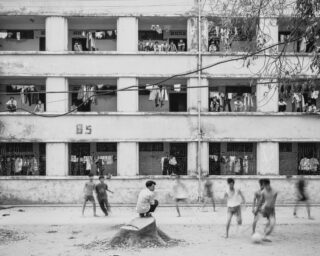

In 2003, the Chinese filmmaker Wang Bing, then an unknown graduate of the Beijing Film Academy, debuted a durational colossus: West of the Tracks, a nine-hour document of industrial decline in the Tiexi factory district of Shenyang Province. Amassed over four years with little more than an amateur video camera and faith in the instructive texture of reality, West of the Tracks found a new form for the chasmic infrastructural changes of post-Socialist China.

Immense run times and handheld spontaneity have come to define most of Wang’s subsequent films, each teeming with the minutiae of daily subsistence in various pockets of regional China. Although Wang is attuned to the present, his work is always marked by a broader intuition of historical process and state-led economic restructuring. His subjects have spanned the extractive labor of oil-field workers on the Tibetan plateau in Crude Oil (2008), the carceral optics of a psychi- atric institution in Yunnan Province with ’Til Madness Do Us Part (2013), and, in 15 Hours (2017), the conditions of migrant workers at a children’s garment factory in Zhejiang Province.

Last fall, these latter two films, along with West of the Tracks; Man with No Name (2010); Father and Sons (2014), which follows the solitary days of a migrant worker’s unsupervised children; and a shorter piece, Traces (2014), were screened as multichannel video installations at Le Bal, a photography space in Paris, in a solo exhibition titled The Walking Eye. For a filmmaker who seems so steadfast in his outward orientation to the world, it’s striking how often he has invoked a vivid subjectivity to describe his output. As Wang recalls about the early days of making West of the Tracks: “I wondered how I could create . . . something singular, something personal.”

Across a two-decade oeuvre laden with the heterogeneous rhythms of life in contemporary China, what is “personal” in Wang’s work is not its proximity to his own biography but to a deeply embodied experience of discovery made possible by his filming. Wang seems prone to self- effacement—no on-screen appearance; only the rarest flashes of his voice as interlocutor—but his physical presence is both anchor to and genesis of every film. Even as he enlists a stray assistant here and there, Wang is the very force that walks the camera’s unblinking eye.

Against his categorization as a maker of documentaries, Wang has stressed a different impetus: “The most important thing for me is to film people and to understand why and how I film them. Whatever story and whatever kind of cinema that may produce.” Wang’s films exceed the mere accrual of information. We learn, for instance, that the metal- workers in West of the Tracks undergo mandatory hospitalization to treat the lead that has leeched into their bodies. Where another filmmaker might briefly limn this as a sobering medical fact, Wang lingers on the eventless days of he workers’ confinement, as they sing karaoke together in scantly furnished rooms, lounge and rove listlessly through hospital halls awaiting their release.

In the usual context of their single-screen display in cinemas, the audience is asked to move through factories and fields, following a figure from behind or stuck to whichever lone purview Wang has framed. But the multiscreen installation of The Walking Eye alters the experience. Of the five films in the exhibition at Le Bal, only Father and Sons was screened in its entirety; the others were presented as curated sequences approved by Wang himself, split across two or more screens. If the theatrical presentation of Wang’s filmmaking invites a kind of temporal immersion into one monumental trajectory, their multiplied projection in the gallery seems to pull apart their layered rhythms, as if to unveil all the dense strata that comprise any given moment in history.

All works courtesy the artist and Galerie Paris-Beijing and Galerie Chantal Crousel

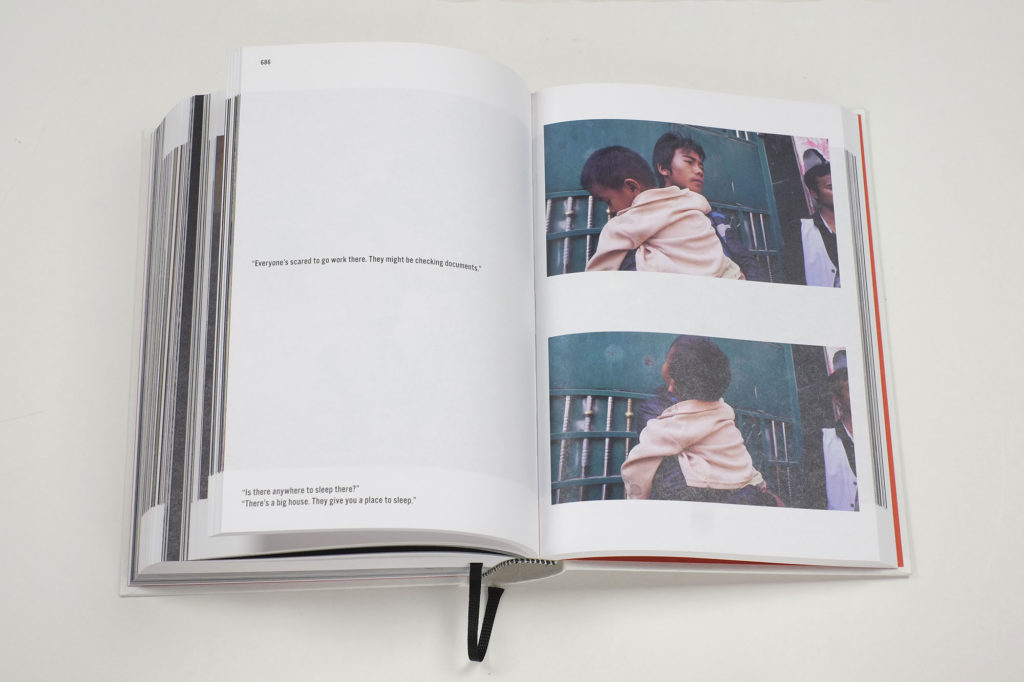

There is a similar effect in The Walking Eye, the eponymous book published by Roma Publications for the exhibition. Of its over eight hundred pages, more than seven hundred display stills and translated text from eight of Wang’s films. Most of these are single images that bleed across two pages, sandwiched like centerfolds, or vertically stacked, two stills to a page. Some are further miniaturized and arrayed as four—maybe six, maybe eight—frames in quick succession, trained on the unfolding of a specific scene. Any print-based documentation of moving-image work is fated to stasis, but the unusual heft of The Walking Eye is, admittedly, confusing. Why freeze and compile thousands of images from a filmmaker who has said, in an interview closing this very book, “I conceive of the camera as the instrument of movement”?

These arrested frames risk turning real-time discovery into fixed curios of an ethnographic other. Wang knows that the “movement” of a world as it becomes known—as it draws us into its opening— cannot be pinned down and collected. If anything, The Walking Eye in book form shows us the limits of fixing moving-image art on the printed page and, in the end, the power of Wang’s films in motion.

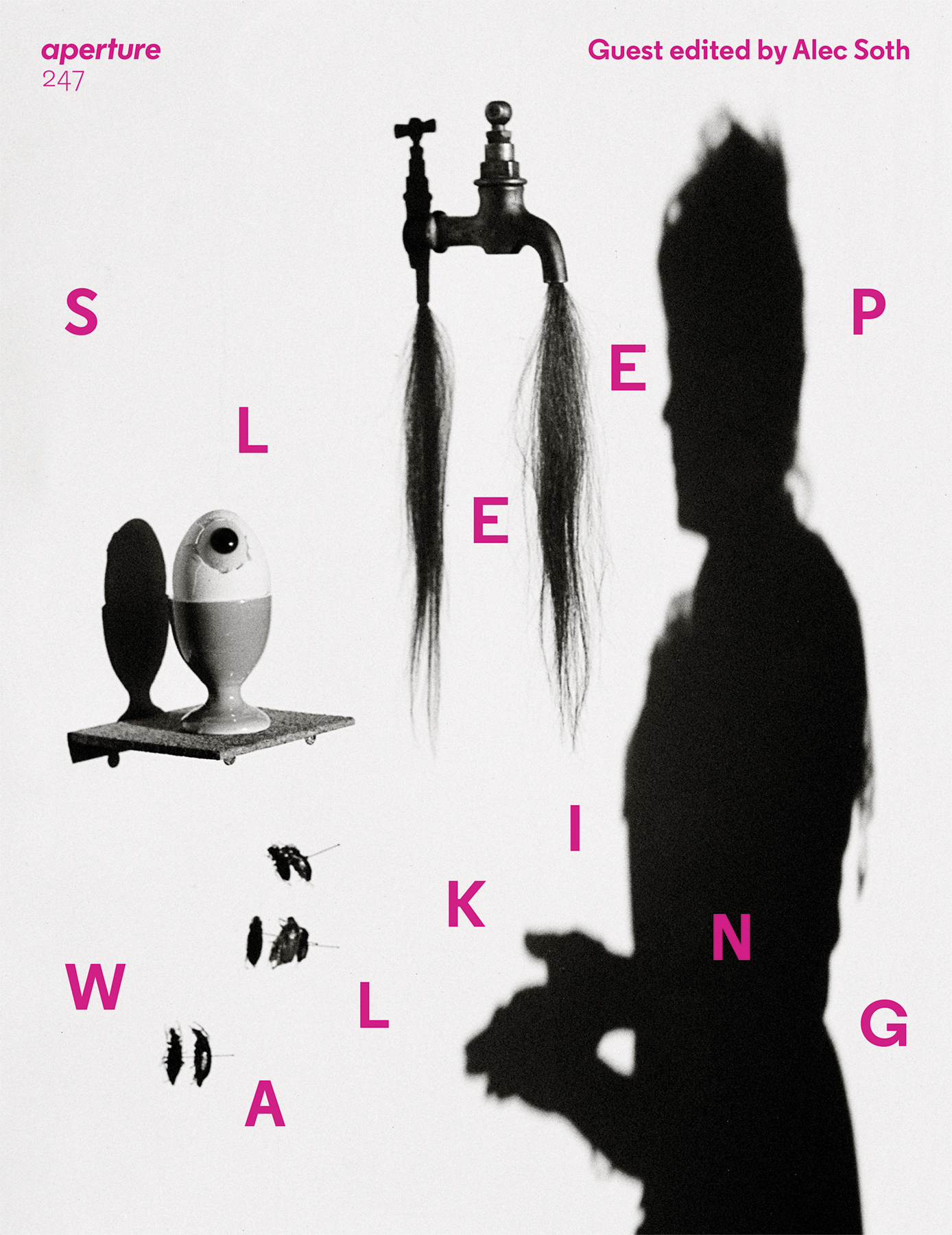

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” under the column “Viewfinder.”