David Benjamin Sherry, Río Grande del Norte National Monument, New Mexico, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94

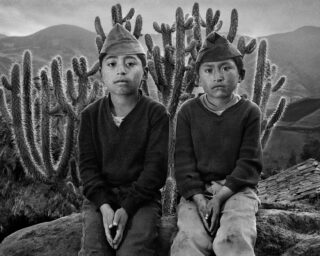

Before you’ve seen the West, you’ve seen the West—landscape photographs of the region, especially those by Ansel Adams, are so deep in our nation’s collective imagination that you have to work to actually see Half Dome, in California, or Shiprock, in New Mexico, even when you’re standing there with your hiking boots on.

David Benjamin Sherry’s recent pictures help us see again. Sherry is known for his fascination with color, for his analog techniques, and for what some have called his “queer revision” of the rugged and macho legacy of western landscape photography. His images of several national monuments, photographed last year, carry the same level of detail as Adams’s iconic pictures, the sublime clarity of the haze-free western summer afternoon. But drenched in unexpected and unreal color, they get you to take a second look.

And in this case, a second look is helpful for any number of reasons.

For one, looking backward, the great protected areas of the nation are not simply blank slates, empty wastes. They were often the homelands of this continent’s original inhabitants, and so they tell, among other things, the stories of our nation’s original shame. Their very emptiness is a reminder of what we did—all the more telling when the petroglyphs left behind at places like Bears Ears, the national monument in Utah, make clear what a bustling place it once was. These lands are as sacred to Indigenous cultures as they ever were, but there’s a tragic quality to that reverence now.

For another, looking forward, these same lands are no longer as sacred to the colonizing tradition as they once were. One of the great boasts of its legacy was the protected landscape: in the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth, we felt ourselves rich enough to methodically put aside large tracts of land for the benefit of the rest of creation, or the future, or our idea that there was something lovely about wildernesses, even ones we might not see. Congress never got more poetic than with the Wilderness Act of 1964, with its commitment to protecting places “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Aside from the questions already raised about who was there originally, and aside from the obnoxious use of man that belies the text’s birthdate, the statute still marks something powerful: even in the middle of America’s great postwar boom, the understanding that we needed something more than we had.

But we don’t think that anymore. Or at least, at the moment, those in charge don’t think that. President Donald Trump, among his endless provocations, has begun trying to roll back the protections of an earlier era, beginning with the national monuments pictured in Sherry’s images. For no reason other than to undo the work of the bigger souls who came before him, the petulant boy king has begun to take apart the network of protected areas that is one of the country’s great legacies. Actually, of course, there is another reason: the fossil fuel industry covets these lands, just as it covets the Arctic, and the offshore lease holdings along the North American coasts, and pretty much every other piece of real estate on the continent. Not content with merely destroying the planet’s climate, it must also do what it can to wreck the loveliness that has been set aside.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Salon 94

Somehow the saturated and unsettling colors of Sherry’s photographs of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, in Utah, and the Río Grande del Norte National Monument, in New Mexico, among other western vistas, help us see all that splendor, all that history, and all those politics more clearly, or at least glimpse that something has gone wrong and is now going wronger in these places that have long been a comforting part of the landscape of the mind. No longer retreats or redoubts from the overwhelming bleat of our wired world, they are contested places. We must fight to make sense of them, and we must fight to preserve them, and we must fight to make sure that in their preservation they connect us back to the people who wandered them originally.

Iconic images have their place—but iconoclasm has its place too.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 234, “Earth.”