Oumou Diarra, Les Chasseuses de Bazin, 2016

Courtesy the artist

In 1998, I traveled to Bamako for the first time to attend the third edition of Bamako Encounters: African Biennale of Photography. At the time, I was an independent curator based in London, and was thus humbled and refreshed to learn that a space existed on the continent for presenting the work of photographers of African descent—many of whom had yet to gain recognition in the West. Since that eye-opening experience, I’ve followed the evolution of the Bamako Biennale, the longest running platform for photography in Africa, by attending nearly every subsequent edition in various capacities—as a spectator, presenter, curator, and, most recently, in 2015, as the artistic director for the tenth edition.

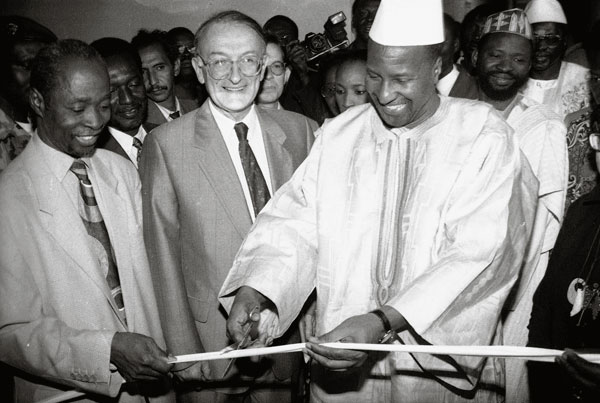

Titled Telling Time, this edition marked a milestone in the Biennale’s history on a number of levels. Not only was it celebrating the tenth anniversary of the event, but Telling Time also heralded the Biennale’s return after a four-year period of absence due to the political instability and threats to Mali’s sovereignty brought about by the jihadist insurgency of 2012. This confluence of political upheaval and cultural expression dates back to the very conception of the event. Mali’s first democratically elected president, Alpha Oumar Konare, staunchly supported the Biennale’s founding in 1994, envisioning it as an opportunity to test the capacity of culture to rehabilitate the nation’s image and restore international confidence following decades of violent authoritarian rule under Moussa Traore. For the tenth edition, local stakeholders renewed their investments in the power of culture by once again positioning the Biennale as a tool for strengthening Mali’s fragile democracy and increasing its international visibility.

Courtesy the artist and Collective 220

I view my role in the tenth edition as part of the efforts to reinvigorate the local, insofar as the responsibilities granted to me marked the first time in the Biennale’s history that a curator based in the region (in 2007 I founded the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos) was chosen as the artistic director. Intimately familiar with the Biennale’s history and evolution, I accepted the challenge of devising an expansive program that would honor the event’s influence, question its place and relevance to current lens-based practices and discourses in Africa, and proffer possibilities for the Biennale’s future. This multiplicity of perspectives animated the conception and execution of the tenth edition’s focus on questions of time and of the local.

The coexistence of different temporalities is a defining characteristic of Bamakois urbanism. Bamako is a place where the past unavoidably engenders a symbiotic meeting with the present, a place where tradition and heritage are at one with modernity. From these perspectives, I consider Bamako a “city village” where tall modern buildings rise in close proximity to modest residential dwellings of neotraditional design, and modern cars mingle, at times, with animal-driven carts. While these characteristics make Bamako an ideal site for discursive exhibition platforms, it should be noted that Mali is one of the least economically prosperous countries in the region. On first sight it lacks the infrastructure to host international art happenings: there exist no degree-granting educational establishments providing photography courses at any level; there is virtually no collector base; and there are no major art-publishing initiatives, to name a few enabling prerequisites.

© the artist

But Mali has a deep cultural past with a long and strategic history. By the fourteenth century, the University of Sankore in Timbuktu had established Mali as an internationally renowned site for Islamic study, with ancient manuscript traditions dating back to the eleventh century. It is the land of the griots and the country of the Dogon people, and of the fourteenth-century magnificent mud mosque in Djenne. Its empires and its emperors, such as Sundiata Keita and Mansa Kankan Musa, are legendary. Malians today remain fiercely proud as well as protective of this cultural heritage. Even in the absence of purpose-built contemporary art venues in Bamako, the Biennale benefits from adequate venues like the Palais de la Culture, the main site of the Biennale before its transition to the National Museum of Mali; the Musée du District de Bamako; the Modibo Keita Memorial Centre; and smaller informal spaces around the city. With this structure, it is no surprise that Bamako would stake a claim as the “capital of photography” on the continent, a status that endures but that may be undermined by increasingly inadequate official support.

The Bamako Biennale started in 1994—founded by French photographers Françoise Huguier and Bernard Descamps—two years after the Dak’Art Biennale in Senegal positioned itself as a forum dedicated to contemporary art. Both can be considered the result of the proliferation of mega-exhibitions and biennials that were springing up in so-called margin locations around the world in the 1980s and 1990s. But most importantly, these two events were responding to the absence of platforms for African artists within and outside of the continent, and to the visibility of the growing number of artists working in Africa and the diaspora. They provided important meeting points for artists, curators, writers, editors, and other art professionals to meet, interact, and exchange.

© Archives de l’Agence Malienne de Presse et de Publicité, Bamako (AMAP)

Consequently, the Bamako Biennale, through its focus on photography, has directly and indirectly spurred a plethora of lens-based platforms and smaller initiatives across the continent. One of the earliest, though short-lived, was the Rencontres du Sud (Southern Encounters), started by Ivorian photographer Ananias Léki Dago in 2000. Other events included Rencontres Picha, in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, started by Congolese artist Sammy Baloji in 2008; Addis Foto Fest, founded by Ethiopian photographer Aida Muluneh in 2010; and LagosPhoto, developed by Nigerian cultural entrepreneur Azu Nwagbogu, also in 2010. These events have been supplemented by new artist collectives such as Invisible Borders, a pan-African collective of photographers and writers who travel by road across Africa, as well as new educational programs and workshops that have manifested

Unlike the major biennials, which often become instruments of governmental politics, the foregoing artist-led initiatives are grassroots organizations that have been cultivated from the ground up, providing training and professional development—in the absence of appropriate education initiatives—with exhibition-making. In addition, they impose no geographical limitations to participation, arguing that international or transnational integration takes cognizance of global parameters.

Despite the profusion of platforms in Africa, which are poised to continue, it becomes necessary to question whose interests are ultimately served through the development of these initiatives, and how, if at all, they harness local infrastructural growth with international visibility. When the Bamako Biennale began, it had a local premise. It symbolized the nation’s embrace of democracy and was supported by President Konare, who understood the role culture could play after the end of a prolonged dictatorship. However, there were tensions from the beginning as to what a French-Malian partnership might look like. From the outset, France played an integral role in the production of the Biennale. Although Mali is now more involved in management decisions, the French have been criticized for their neocolonial relationship regarding the event. Nevertheless, the original aims, which sought to foster collaborations and develop the embryonic field of African photography, as well as the local scene, have seen tremendous success.

Courtesy the artist

There have been many local beneficiaries of the Biennale, some more successful than others. In the early editions, Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, already with burgeoning international careers, were catapulted into foreign museums, galleries, and collections. In 1994, the Malian government announced its intention to found the Maison Africaine de la Photographie—finally created in 2004—to strengthen the presentation and dissemination of photography across Mali and neighboring countries. Education centers, especially the Cadre de Promotion pour la Formation en Photographie (CFP), established in 1998 and generously funded by Helvetas Mali, produced a new generation of photographers. Promo-femme: Center for Audio Visual Education for Young Women was created in 1996 to develop and nurture the first generation of women photographers, including Fatoumata Diabate, Amsatou Diallo, Alimata Traore, and Penda Diakite (who opened her own studio in 2002, considered the first by a woman in Mali). Over the course of its existence, numerous women were trained and some participated in the Biennale, such as Diabate, who won the Afrique en Création prize during the 2005 edition and has since gone on to develop her career internationally.

© Érika Nimis

While Keïta and Sidibé were accepted and acknowledged as national treasures at home who catalyzed the developing Malian art photography scene, their celebrity status—due to important group exhibitions such as Africa Explores, curated by Susan Vogel in New York in 1991, and Keïta’s 1994 solo exhibition at Fondation Cartier in Paris, for example—has contributed inadvertently to the eclipse of equally important and impressive Malian studio photographers including Adama Kouyate, Mountaga Dembele, Abdourahmane Sakaly, and Tijani Sitou, among others. Unfortunately, it also has had repercussions for the next generation of photographers, such as Racine Keita, Mamadou Konate, Emmanuel Bakary Daou, Alioune Bâ, and Youssouf Sogodogo, who all have been creating important bodies of work since the 1980s. Although some of this photo-based work was shown during the first or second editions of the Biennale, these photographers have not been able to sustain interest in their work once it fell outside the genre of studio photography, which continues to govern associations and expectations for photography in Mali.

By the third edition in 1998, when the event began to take on a more international outlook, the possibilities for inclusiveness became limited, with the participation of Malian artists becoming overshadowed by the scale of the Biennale and the broader inclusion of international artists. Some of the early attempts at consolidating the local sector were short-lived, despite a period of increased funding. With the appointment of Paris-based, Cameroonian curator Simon Njami to head the next four editions, from 2001 to 2007, the international status of the Biennale was confirmed, and so too was the consolidated influence of the French government on the event.

Not dissimilar to the climate in which the Biennale was founded two decades ago, Telling Time developed during a period of optimism after the fall of a dictatorship and a four-year hiatus due to insurgency. The tenth edition provided an opportunity to look back in order to move forward. It was obvious that neither the country as a whole, nor the Biennale as a single, though crucial, entity, could continue without tangible integration with, and benefits to, the local population. The key question for the tenth edition was how to deviate from abstract pronouncements of local engagement and develop concrete programs within the Biennale that were locally conceived—in essence, how to make the Biennale a local event with international visibility.

© the artist and courtesy 10th Rencontres de Bamako

This approach was reflected in Telling Time, which I conceived in collaboration with two associate curators, Antawan I. Byrd and Yves Chatap. The edition’s substantial Focus Mali program was instituted through a rigorous consultative process. It was an attempt to kick-start the long journey back “home.” As director general Samuel Sidibé signals in the Biennale publication’s introduction: “The local engagement is one of the major pillars on which this edition was constructed.” Focus Mali included an exhibition of work by a new generation of Malian photographers organized by Malian curator Amadou Chab Touré; an invitation to twenty photography studios across all the boroughs of the capital to collaborate on presenting their archives in mini-exhibitions that were co-organized by Malian journalist and cultural producer Amadou Sow; and an ambitious educational workshop that involved sixty-four schools, reaching approximately five thousand students. The local and the international, pedagogical and scholarly, historical and contemporary coalesced in the tenth Biennale and also in its expansive publication, which was itself conceived to be a dynamic platform under the art and editorial direction of Byrd.

Questions of sustainability naturally circumscribed the development of the Biennale, as they do in most places. Like the Dak’Art Biennale, the Bamako Biennale suffers from the grip of government departments at home and abroad. But one aspect that brings a sparkle of hope is the growing visibility and dynamism of the event’s large and growing OFF program, initiated by local artists. Malian photographers are increasingly overcoming the limitations of local professional development and education initiatives by traveling in Africa and abroad for residencies. The path to cultural self-determination and articulation is visible with locally driven projects, including Emmanuel Bakary Daou and Patrick Ertel’s Espace Photo Partagé and its monthly Bamako Samedi Photo; the dynamic Medina Gallery, founded by social and cultural entrepreneur Lassana Igo Diarra; and Photo Kalo, the Month of Photography, started modestly in 2016—all of which might provide needed, year-round activities to position Bamako as a hub of cultural activity beyond the Biennale. Only time will tell.

This article originally appeared in Aperture issue 227, “Platform Africa.”