Notions of Land

Meryl McMaster, Bring me to this place, 2017

Courtesy the artist; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, Montreal

Imagine a lonely warrior slumped over his horse, backlit by a sun setting over rolling hills, or a group of warriors riding off toward the horizon. It isn’t hard for most people to conjure because we have been raised on these romantic images of the so-called vanishing Indian. Photography, which developed hand in hand with colonialism, has largely been responsible for the continued stereotype of the noble savage. What “Indians” are admired for—the idea of being one with nature, one with the land and animals—is also seen as the source of their inferiority and inevitable demise. It is given as the main reason they are unable to survive in modern society: “Indians” are part of nature, not civilization, and, by extension of this argument, less than human.

American photographers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, like Edward S. Curtis and Joseph Kossuth Dixon, to name only the best-known, used photographs to link Indigenous Peoples to the idea of “nature” in order to speak about the end of Indigenous “nobility”—an end that was connected to the introduction of supposed “civilization” in the form of white-settler communities. Photography itself was considered part of the proof of white superiority because of its basis in technological innovation.

All stereotypes have a minor truth to them: in this case, it’s true that Indigenous Peoples have a kinship with land and animals. We do think that all living things have a spirit. The idea that the earth is our first mother and that animals are our kin and can communicate with us through visions, dreams, and signs is central to many Indigenous cultures. But is this all based on clichés and superstitions? No. These facts were deeply misunderstood and parodied for the sole purpose of justifying the removal of bodies blocking the path of settler colonialism; today, this view is used to rationalize the extraction economy as well. In recent photographic works, a number of Indigenous artists are beginning to debunk these colonial “facts” and counter them with deeper understandings of our relations with “nature.”

Robert Kautuk, Walrus hunt near Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada, July 22, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Robert Kautuk, from Kangiqtugaapik (Clyde River) on Baffin Island, in Nunavut, Canada, uses photography to document the daily life of an Inuit community, in particular their relationship to the land, weather, and animals. For me, a southerner, viewing his aerial photograph Walrus hunt near Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada (2016), of an ice floe covered in blood after a successful walrus hunt, is almost surreal. South of the Arctic, this is not what our hunting looks like. In Kautuk’s photograph, the red bloodstain spreading across beautiful white ice is set against the deep blues of the Arctic Ocean. There are minute details of hunting gear, a small boat filled with necessary supplies, and people braiding intestines. You want to look closer at this almost dollhouse-scale perspective, which was taken with Kautuk’s Phantom 4 drone rather than his digital single-lens reflex camera.

Kautuk also employs his skills on a digital mapping project called the Clyde River Knowledge Atlas (2015–ongoing), which draws on elders’ and harvesters’ knowledge of local Inuit place names and the environment. The atlas is an important tool for sharing resources on environmental assessments, changes, and uses, and the names for places in the Inuktitut language are critical for determining the locations of people who find themselves in an emergency. Kautuk’s photographs and the new atlas may also have a lasting impact on Inuit communities’ ability to assess the desirability of outside development projects. In 2017, Clyde River won a Supreme Court of Canada fight over the National Energy Board having granted permission to energy companies to do seismic testing for underwater oil in Nunavut. The court justices ruled that the NEB had trampled Clyde River residents’ rights as Indigenous Peoples and had failed to consider the necessity of subsistence hunting for Inuit existence. Clyde River’s former mayor Jerry Natanine, who fought for years to have this Inuit way of life acknowledged and respected, felt vindicated by the ruling.

Kautuk, in his way, is doing the same by preserving the beauty of the land and of the hunt; Walrus hunt near Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada gives intense presence to Inuit survival. Unfortunately, the hunt, especially of seal, has long been misunderstood by southerners and Europeans, often in the name of environmentalism and ecology. Many people do not understand that grocery-store food is very expensive in Nunavut and often just not available, so hunting is the only way to eat. A diet of whale, walrus, seal, arctic char, and bear is also healthier physically and spiritually for the Inuit people. Hunting is tied to cultural practices that keep alive ways of being that hone the collective spirit through sharing, honoring, singing, and remembering the hunt. In this context, a photograph of a walrus hunt is an act of resistance.

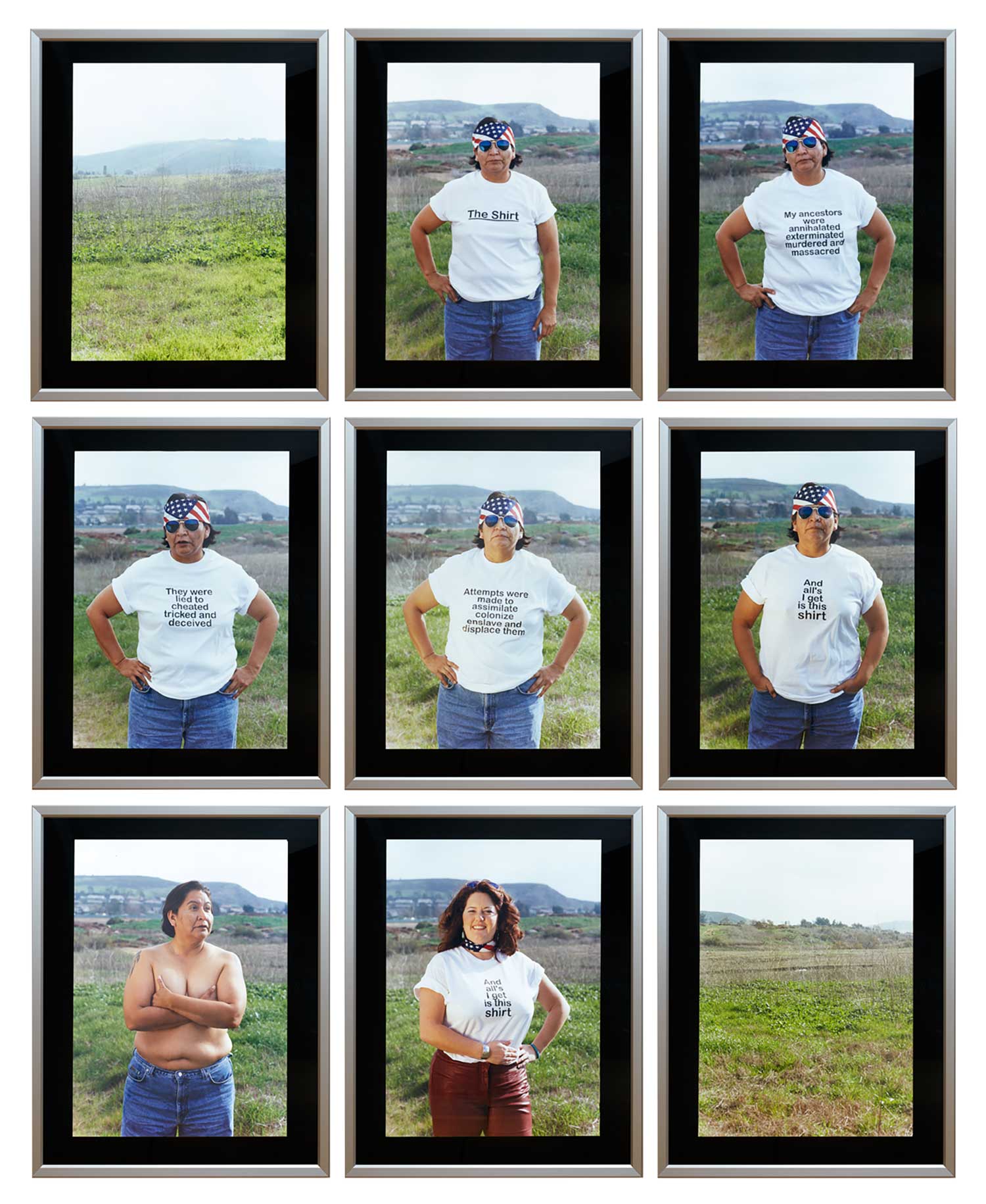

Shelley Niro, The Shirt, 2003

© the artist and courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario

The ways in which photography can express Indigenous presence on the land also include more conceptual, performative work, such as Shelley Niro’s series The Shirt (2003). Niro is a member of the Turtle Clan of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation. The Shirt is a unique set of nine photographs that, taken together, create a narrative of Indigenous sovereignty where women are central. Niro often constructs her photographs by having people perform for the camera; in this case, her friend and fellow photographer Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, of the Taskigi Nation and Diné Nation, faces the lens, confronting the viewer directly. She is photographed in the landscape wearing a series of five T-shirts that sequentially say: “The Shirt”; “My ancestors were annihilated exterminated murdered and massacred”; “They were lied to cheated tricked and deceived”; “Attempts were made to assimilate colonize enslave and displace them”; “And all’s I get is this shirt.” In the sixth image, she appears without any shirt; in the seventh, a smiling white woman wears the final shirt of the series. These seven photographs are flanked by images of the land, underscoring the importance of land rights to Indigenous struggles for self-determination. In Niro’s work, the shirt becomes a souvenir from the highway of colonialism, ripped off the backs of Indigenous women who live there. Because the shirt is an object many people have encountered and is a form of self-expression, statements about the colonial land grab become readable and relatable to a broad, diverse audience.

According to Niro, “The Shirt series came about as I flew over the Texas landscape. I looked out of my window and saw the land below chopped up into squares, each square neatly fenced off from the other. I thought about the ‘Indians’ who fought for that land, as well as the sacrifices made by tribes and nations in their efforts to keep away the settlers from their land and communities. Hulleah’s presence gives the series seriousness and strength.” The presence of a Diné woman in this terrain also draws attention to the connection between violence against Indigenous women and the land: in an extraction-based economy, “man camps”—sites of temporary worker housing—spring up, and violence against the local Indigenous women also rises. Historically, as well, colonization has specifically targeted women, reducing them to the property of men under many policies and laws, including the 1876 Indian Act in Canada. Niro “believes narrative delivers a personal contact with the viewer”; her work asks viewers to be actively and empathically engaged, to place themselves in relation to the narrative as perpetrators or survivors of colonialism.

Jeff Thomas, Bert General Husking White Corn, Six Nations of the Grand River, 1980, from the series Corn Husks

Courtesy the artist

Walking the line between construction and documentary is Onondaga photographer Jeff Thomas, who grew up in Buffalo, New York, and is a member of Six Nations of the Grand River. When Thomas visited the Six Nations reserve in Ontario, Canada, in the 1970s, he was taken with photographing the homes and daily lives of elders, resulting in his series Corn Husks (1976–2011). He states that his step-grandfather “demonstrated how to weave the corn leaves into long strands…. The act of weaving corn leaves into a braid is a symbol of the Indigenous teaching that all living things are interconnected.” Thomas purposely photographs the process of creation rather than the finished product, citing the bodily memory that is the basis of cultural knowledge. In the image Bert General Husking White Corn, Six Nations of the Grand River (1980), the movement of ripping husks from corn is culture in action. Thomas sometimes juxtaposes his images with archival photographs to create more complex narratives; White Corn (2014/2017) is composed of three photographs by Thomas and a fourth taken in 1912 by English anthropologist Francis Knowles, titled Chief Jacob General. These photographs are laid out like a wampum belt, a traditional medium for passing on oral history; Thomas uses photography as memory in place of wampum beads.

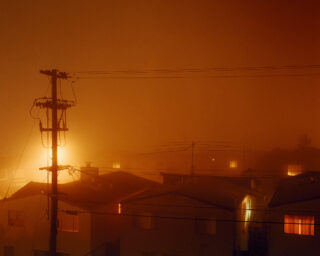

The way the physical environment can evoke centuries-old knowledge and function as a kind of memory making for Indigenous Peoples also informs the photographic practice of Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) artist Greg Staats. In the striking work untitled (restraint_constraint) (2015), he delves into the psychological aspects of place. A tree trunk with roots still embedded in the earth but with many severed parts fills almost the entire image plane; only a slight vision of concrete appears in the background. The work evokes a liminal space between the grounded and the uprooted while giving no particular markers of place. Staats describes his practice as “in service to orality of place and natural world mnemonics—objects/images and place share a long wordless relationship reunited to further their cause of holding together the unsaid.” The trunk becomes a poetic rendering of Indigenous Peoples finding their way back home through the trauma of colonialism, which has left many with severed roots.

Greg Staats, untitled (restraint_constraint), 2015

Courtesy the artist

The land as a carrier of traumatic memory also forms a backdrop for Cree artist Meryl McMaster’s latest photographic series, Edge of a Moment (2017), made in Alberta at the Head- Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. This spot was once key to Indigenous survival, especially for the Cree and Blackfoot of the prairies. Here, they would run buffalo off the cliff in huge herd hunts; such hunts occurred up until the 1880s. Settlers and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police massacred the buffalo almost to extinction to starve Indigenous Peoples onto reserves. McMaster uses herself as a model, constructing elaborate costumes to wear in these conceptual photographs. In the series, she a wears a coat covered in a printed chicken-feet pattern along with a hat fabricated from prairie chicken feathers. McMaster explains, “The feather bustle we see male traditional dancers wear is modeled after the chicken’s tail feathers. I use their tracks in an abstract way to cover the garment I am wearing within the image. Their absence represents to me not only the dangers of the unsustainable use of the land, but also the human consequences of colonization and settlement.” As McMaster makes clear, photography in the hands of Indigenous artists forms a body of philosophical, poetic, and physical knowledge of our relationship to land and the history of colonial ruptures. Photographs provide forms of visual sovereignty and assert a continued presence on the land, despite centuries of theft and removal.

Read more from Aperture issue 234, “Earth,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.