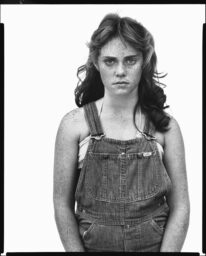

Rosalind Fox Solomon, After 9/11, MacDowell Colony, New Hampshire, 2002, from the series Self-portraits

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” Fall 2015.

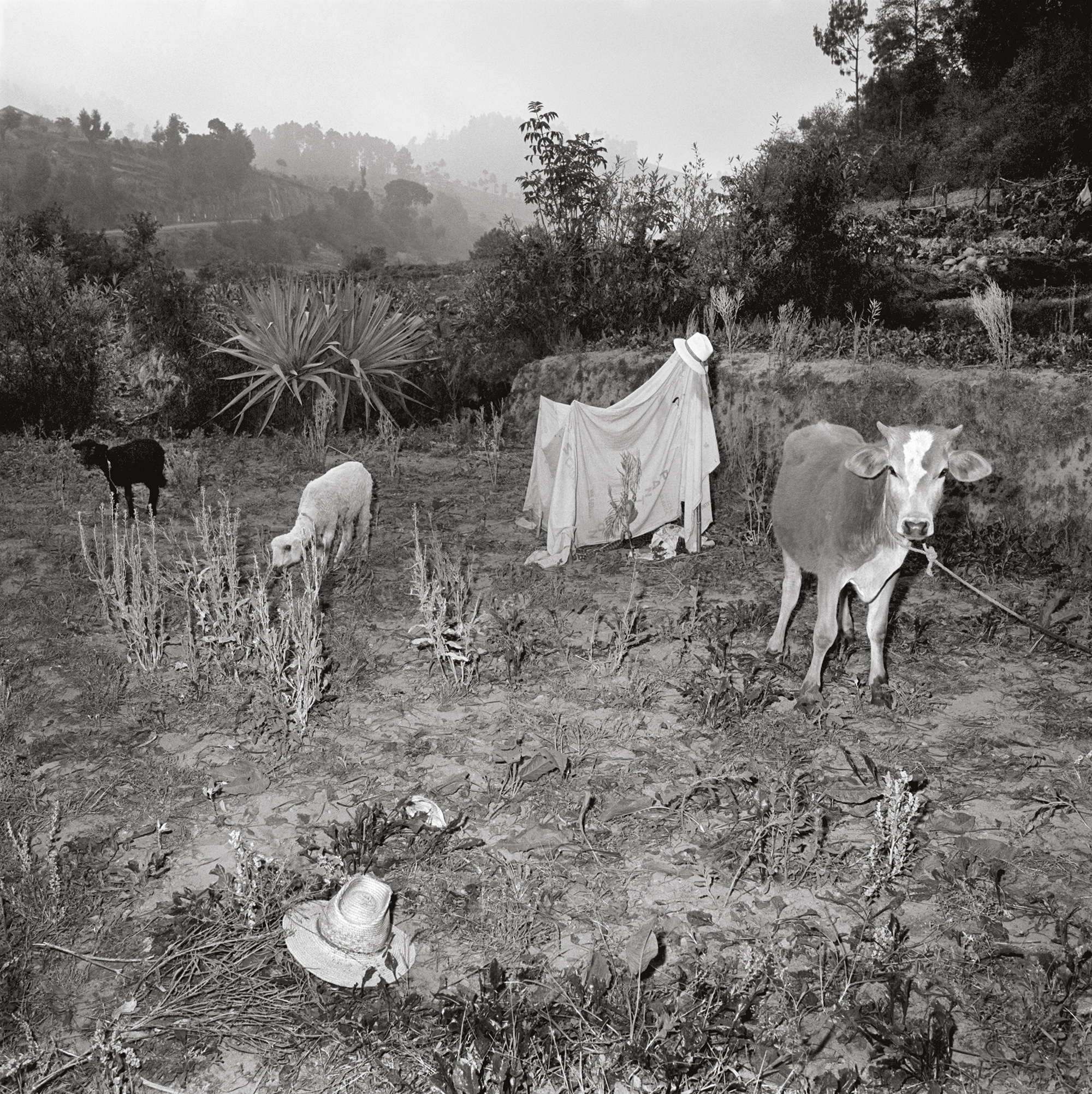

Fox Solomon’s photographic career has been defined by an itch for travel and a desire to use the camera as a means of self-discovery, or, as she puts it, as a way of “talking to myself.” A student of photographer Lisette Model, who was known for her confrontational images of New York City’s street life, Fox Solomon, over many decades, has photographed extensively in South and Central America, India, and Poland—as well as in places closer to home, like New York and the American South. Her work, however, is often metaphorical, transcending mere descriptions of place. Since 2010, she’s been working in Israel and the West Bank as a contributor to a project called This Place, along with eleven other acclaimed photographers, among them Josef Koudelka, Jeff Wall, Stephen Shore, Thomas Struth, and Wendy Ewald. A new book, provisionally titled Noodles and Navels, which looks at Fox Solomon’s childhood, parents, marriage, and liberation, is due out from MACK early next year.

When we asked Fox Solomon with whom she might be interested in speaking with for the Fall 2015 issue of Aperture, “The Interview Issue,” she replied, “a woman who writes for the New York Review of Books.” Novelist Francine Prose—a regular contributor to the NYRB—agreed to conduct the interview, meeting with Fox Solomon last April at her home in downtown Manhattan, where the two spoke about the trajectory of Fox Solomon’s career and her leitmotifs of ritual, religion, gender, and travel.

Francine Prose: Can you remember the first picture you took that made you think, Oh, this is really something I want to do, this is going to be my life?

Rosalind Fox Solomon: I didn’t think, This is going to be my life, but I took a picture in Zagreb years ago and called it Caged Woman. It was a woman in a window, with some birds on the outside, and a birdcage on the inside. And it had a lot of meaning for me. I needed space to stretch and grow.

Prose: When was this?

Fox Solomon: I took that picture in 1971 in Zagreb, Yugoslavia. In 1968, in Japan, I first started taking pictures. I was there on behalf of the Experiment in International Living, an international exchange organization based in Vermont. Earlier I had traveled to Belgium and France with the Experiment, when I graduated from Goucher College in 1951.

At that time it was an international exchange program that sent Americans in groups of ten to European communities. The Experiment’s motto was “We learn to live together by living together.” In Japan, my hosts were a Japanese mother and son. I slept on a futon and shared meals with them, but our communication was limited because I didn’t know Japanese. I started taking pictures as a way of talking to myself. I got the sensation of what it was to get something out through a camera that might represent what I was seeing and feeling.

Prose: Do you remember those early pictures of Japan?

Fox Solomon: They weren’t anything, really. I was awestruck by the differences between Japanese culture and our culture. Those first pictures that I took in 1968 were color, but I started taking black-and-white pictures soon after a friend of mine, who was a photographer at the Chattanooga Times, told me that black and white was more expressive than color. He helped me set up my darkroom. The thing that had a lot of personal resonance for me, and that I became very obsessive about, was photographing broken dolls. And that happened in the early ’70s when I went to a market an hour or so from Chattanooga. There were tables of dolls, they’d just thrown these dolls on the table. There’s a very famous photographer—

Prose: Hans Bellmer.

Fox Solomon: I didn’t know anything about Bellmer.

Prose: Good [laughs].

Fox Solomon: He had a different attitude, of course. So, anyway, I did a huge series on the dolls in the early ’70s.

Prose: What was it about the dolls?

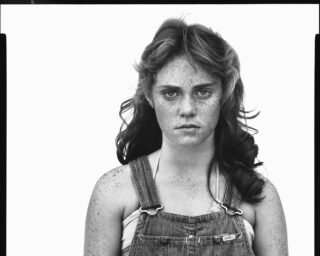

Fox Solomon: I was really living an exterior life. My husband was a shopping center developer. He wanted and expected me to entertain the real estate guys to help entice them to take leases in his shopping centers. That meant I spent tedious evenings with couples whose main interests were cooking and golf. My interests were different. I was involved with community affairs: the League of Women Voters and an adult education group. I began reading The Feminine Mystique (Betty Friedan, 1963). The book made me more discontent. Photography seemed a worthwhile pursuit. I could have control over my work. Maybe the dolls expressed my feeling of just being a little broken. I did a huge series on them—and then I started doing portraits. I started photographing dolls close up and I learned how to take pictures of people that way.

Prose: The dolls didn’t move, they didn’t talk back. You didn’t have to ask them anything.

Fox Solomon: So I just kept photographing, and I learned how to work in the darkroom, and I would stay in the darkroom until two or three in the morning. I got deeply involved with what I was doing. I had a few artist friends who encouraged me. In the early ’70s, I had a show of photographs that I had taken in Scottsboro, Alabama. The pictures were mounted at an artist cooperative in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where I lived at that time. I showed photographs of the dolls and also pictures of people. People came to the opening. They drank the wine and they ate the cheese, but nobody said a word about the pictures. I was crushed because nobody responded. I became withdrawn and quiet. I felt like I had lost my voice. After Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976, my husband was asked to take a subcabinet position in the Carter government, as administrator of the General Services Administration. My husband had been active in local politics, was a commissioner on the Chattanooga Housing Authority, and worked on the Carter campaign. I was beginning a new project photographing and interviewing Tennessee doll collectors. At first I was distressed about moving, then I realized that life in a new environment was an opportunity for change. In D.C. we were invited to parties galore. There were place cards and I found myself seated between strangers. I was no longer mute.

Prose: You were taking pictures of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, right?

Fox Solomon: I photographed Jimmy and Rosalynn during the election campaign, but in Washington, I got limited access. I rented a small space and set up a small darkroom. There was a closet where I rolled film and a bathroom where I developed it. I photographed outside the White House repeatedly, senators, congressmen, and artists—William Christenberry, Gene Davis, Sam Gilliam. I visited and photographed William Eggleston in Memphis and drove around Mississippi photographing many of his relatives.

Prose: How did you start working with Lisette Model?

Fox Solomon: Modernage lab led me to Lisette Model. Though I worked in the darkroom, I didn’t know what I was doing. So when I got to New York, I took my film to the Modernage photo-lab and had prints made. I went to their Christmas party in 1971 or ’72, and I met a photography agent, Henrietta Brackman. She made an appointment with me, saying, “Bring everything you’ve ever done.” I said, “I can’t. There’s too much.” She said, “You have to bring everything you’ve ever done.” I brought two huge suitcases full of things, and after she looked at my pictures, she said, “You have talent but you need help. You should study with Lisette Model. She was Diane Arbus’s teacher.” Diane Arbus and Ansel Adams were the only photographers I had heard of at that time. I got in touch with Lisette and she said, “The next time you come, meet me and bring everything you’ve ever done.”

Prose: You already had it packed in the suitcases.

Fox Solomon: The next time I got to New York, I brought everything I’d ever done. Lisette came to my hotel room, and she looked at my pictures from six o’clock until midnight. Finally, she was too tired to go on, but she told me that I could study with her. Whenever my husband came to New York on business, I came with him and brought my pictures to show to Lisette.

Rather than make people feel at ease, I find that some tension between me and the person I am photographing yields something more complex.

Prose: And what did “studying” mean?

Fox Solomon: Before we began, Lisette spent a half hour talking about herself and her career. She was blunt and though she had much success early on, getting her work out had become more difficult. She talked about the work of other photographers—the ones she considered authentic and the ones whose

work she did not like because it was commercial or derivative. I got impatient as I listened to her, but eventually, I realized that all of what she said was instructive. Finally, she would look at what I had done and critique the prints. Then she looked at my contact sheets to see what I had not chosen. She said to always go for the extreme. By this I think she meant, Be true to yourself as an artist. Don’t censor yourself. Don’t do your work to please others. She advised, Always make one picture you can give to a subject; otherwise be free in what you do. One of the most important things I learned from her was to take risks.

Prose: Did things change radically when you started working with her?

Fox Solomon: I was in my early forties when I met her. Lisette was a strong influence. She was my mother in art. My birth mother was overly concerned about convention and propriety. Lisette was the opposite. She convinced me that the most important thing in my life was my work. She would say, “You need a close-up lens.” And I’d say, “But that costs so much money.” She’d say, “Can’t you afford it, dahling?” She always pushed me to upgrade my darkroom, to get any kind of camera equipment that I needed, to keep moving ahead. And since my husband always felt it was important for me to buy modish clothes—he really cared about that—I knew that I could certainly afford to buy some camera equipment. I still remember a camera shop salesman who tried to convince me that I did not need to upgrade to a more professional enlarger. Lisette encouraged me to be oblivious to what people thought about me or my work.

Prose: You start off taking pictures of dolls. They don’t talk. But when you begin to take pictures of the living, especially during festivals and rituals, what do you say to your subjects?

Fox Solomon: I don’t say very much.

Prose: You just started shooting?

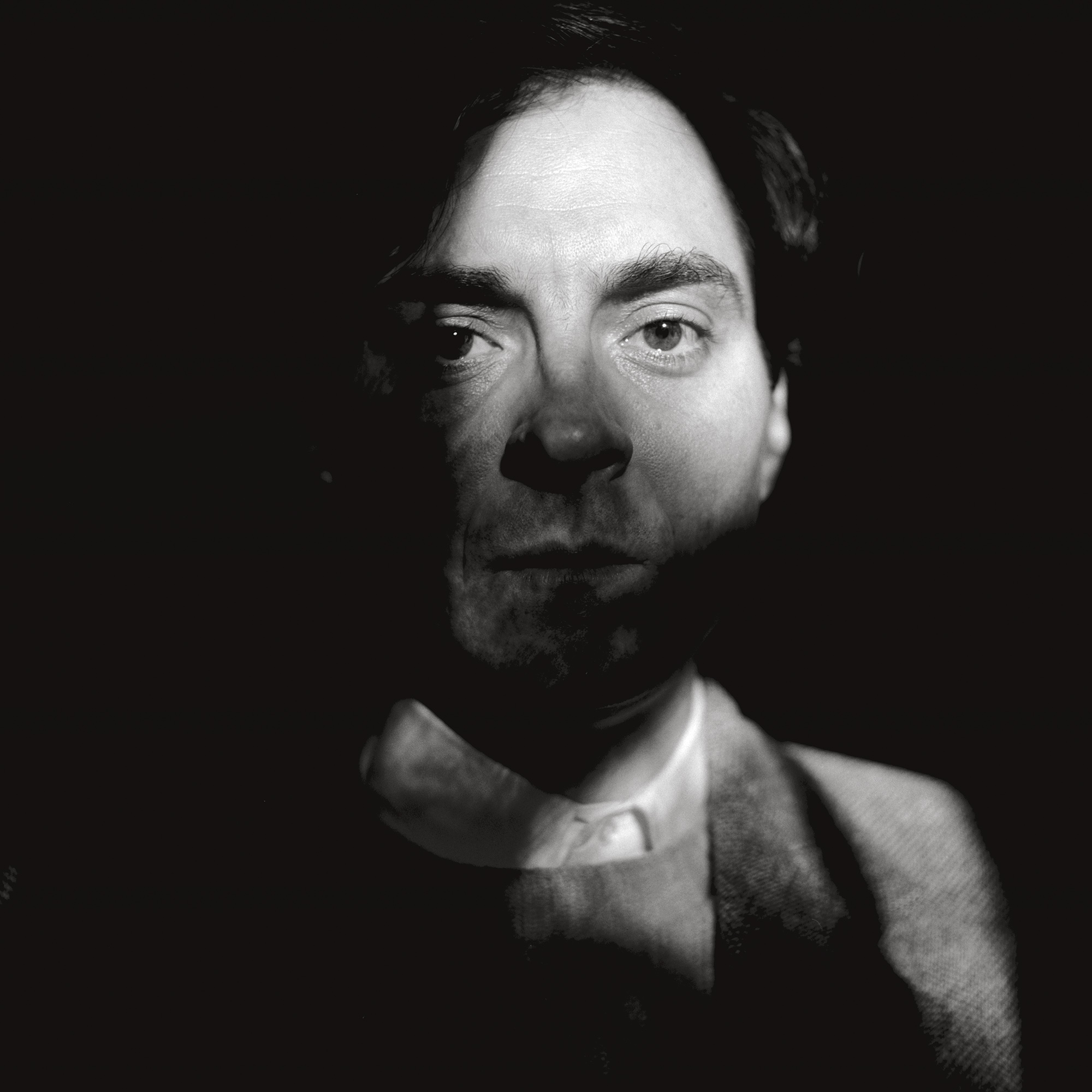

Fox Solomon: In the spring of 1978, I planned a week’s trip to Guatemala with my husband. It was a vacation for him, and an opportunity for me to speak Spanish and take pictures in an environment far removed from life in Washington. After the initial trip, I went back a number of times. I traveled alone with a driver guide. This enabled me to get deeper into my work.

Even though I speak Spanish, I didn’t say very much. I soon learned that if you engage very much, you lose a certain tension in the picture. Rather than make people feel at ease, I find that some tension between me and the person I am photographing yields something more complex. I always traveled with a local driver who spoke to people on my behalf as I began shooting. I carried a Polaroid always and took pictures to give to people after I finished making my pictures. I also brought back proof prints on subsequent trips and gave them to people I had photographed.

I photographed shamans in Guatemala. There was a personal connection. My husband had a progressive congenital disease. Knowing that his mother, aunts, and an uncle had died of the disease, from the time that he found out during the first year of our marriage, I thought about this. I was interested in how other people dealt with sadness. In Guatemala, they coped with the help of shamans, ritual, religion. I encountered people who were in much more difficult circumstances than I could ever imagine. Once I was in a séance in Peru with two shamans, a man and a woman who were reputedly lovers. We were sitting around a little fire in a little hut for a coca séance. They incanted and sang, “Smoke your cigarette and cha-cha your coca.” I told them that my husband was sick. I mean, I didn’t really believe in this. I didn’t believe in it but I just—

Prose: Everybody sort of believes in it.

Fox Solomon: I thought maybe it would be helpful. So I told them about my husband and they took it very, very seriously. They told me that I had to get a guinea pig and rub the guinea pig on the body part that was injured or sick, and presumably the illness would pass into the guinea pig. So they told me to get a guinea pig and rub it over his body.

Prose: How did that play out when you got home?

Fox Solomon: Well—

Prose: So when you found these drivers, you would say, “Do you know any shamans?”

Fox Solomon: Yes. I photographed a lot of shamans in Guatemala. I also photographed landscapes, farmers, and Easter processions. In Peru, my driver was a twenty-two-year-old Chilean named Pablo. His parents had been supporters of Allende and they had gone to live in Germany after Allende was assassinated. Pablo went to Peru and married a Peruvian. Our first trip was idyllic. I had a lot of fun with him. The road up into the Andes was beautiful and untouched. We encountered women carrying spindles and weavers on the side of the road. In reality, people were living hard lives in a subsistence economy, but what was going on then was from another time. On my next trip with Pablo, I planned to photograph carnival celebrations. He sang revolutionary songs and stopped to use binoculars to look up into caves in the mountains. I began to think that he must be involved with the Shining Path [a Maoist guerrilla group]. We got rooms for the night in a pension in a small village. I got up in the middle of the night and went out into the van. I was scared.

At dawn, I went out in the street and talked to a woman, saying, “I’m with a driver and I don’t have confidence in him.” I was afraid to say anything more. She said, “Go to see the bishop.” I told the bishop that I had come to photograph carnival, but I had to leave my guide. He said, “Stay and take your pictures. We will help you.” He introduced me to Madre Rosa Cedro. For a few weeks, I lived in a house belonging to the church that was near the convent and had meals with the nuns.

Prose: Is there a photo of her? Standing by a horse?

Fox Solomon: Yes, I went with her on an overnight horseback trip to a remote area. I went back a number of times to that village.

Prose: Did your interest in illness and healing affect your work with people with AIDS?

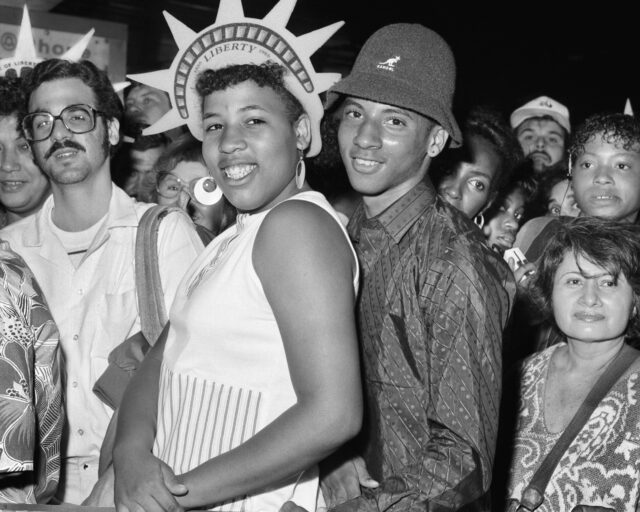

Fox Solomon: In 1988 in New York, I spent a year photographing people with AIDS that resulted in a show at the Grey Art Gallery. My interest in making portraits of people with AIDS was connected to the fact that when my son was in his twenties, I got the heartbreaking news that he had inherited polycystic kidneys. (He had a kidney transplant six years ago and is now well.)

Prose: Most of your work has been documenting other cultures. When did you go to India?

Fox Solomon: The first time was in the early ’70s, with my husband. I was working with a 35mm camera. In 1981, I went on my own with a fellowship from the American Institute of Indian Studies. I went three years in a row to photograph in Calcutta, from ’81 to ’83.

Prose: Did you time your visits to coincide with festivals?

Fox Solomon: Yes, I was there during the fall goddess festivals. But I also photographed the filmmaker Satyajit Ray, and other artists and poets. My guide’s father had willed the family home to the goddess Kali. His brother left his wife and family and established an ashram in the family house where his followers came to worship. He became a guru. When the guru died, I was told that instead of cremating him, they put him into a cage and dropped him into the Ganges, and they brought him up every year during the time of the Kali festival.

Prose: No!

Fox Solomon: Honestly. I went back there.

Prose: What about This Place, the project in Israel and the West Bank that you began in 2010? What did you do there?

Fox Solomon: The photographer Frédéric Brenner invited me to participate as one of twelve international photographers in a project, originally with the working title of Israel: A Portrait in Progress; the idea was to get twelve outside takes on this land with a long and layered history. We were all told to do our own work. I proposed photographing Israelis, Palestinians, and pilgrims. I centered some of my work around religious events and I made portraits of people wherever and whenever I could. I was interested in the unexpected. I had never photographed in a Muslim culture, and because I was painfully conscious of the fraught political situation in the country I wanted to know and understand more. I spent several weeks in Jenin, on the West Bank.

Prose: I love those photographs of the two guys with the tattoos. There’s a guy who has what seems to be a word or phrase in Arabic on his heart, and then there’s a guy with a Jewish star on his arm.

Fox Solomon: The man with the tattoo on his heart told me that his appearance was such that he could

be taken for either Jewish or Muslim. On a bus, after a bombing in Gaza some years ago, he heard horrible things that affected him so much that he went through a long period of depression. My book THEM, published by MACK Books in 2014, includes some of what I heard as I worked on my project.

Prose: Did you go to Israel more than once?

Fox Solomon: I made four trips to Israel during 2010 and 2011. I spent five months photographing for the project. Once I stayed for two months, which is a very long time to stay. It’s hard to stay there for more than a few weeks.

Prose: Why?

Fox Solomon: Because of the stress and the tension. You can’t get away from it, and it’s very heavy.

Prose: Did you know what you were looking for before you went?

Fox Solomon: Not really. I had to write a proposal to say what I was going to do. I was interested in photographing people among groups not usually on the radar. Christians as well as Israelis and Palestinians feel a stake in Israel. I photographed some Christian rites, including pilgrims at the Field of Shepherds in Bethlehem and an Armenian Easter ritual at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. I also photographed Filipino caretakers of seniors, undocumented Africans, Africans who came from Sierra Leone twenty years ago as construction workers and whose children’s first language is Hebrew. It was essential for me to spend time with Palestinians and to understand their lives. This was made possible by Marcus Vetter, a German filmmaker who rebuilt the Cinema Jenin and made films in the town, bringing Palestinian actors and technicians into the process. In Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, I photographed many Israelis. Some of them I met on the street or on the beach. They were strangers who agreed to be photographed. I met others through friends. I never knew how it would all come out. In the end, I chose the best photographs. Among them were some unpeopled images that helped with context.

Prose: There’s a very beautiful picture of a mother and daughter. Is that right?

Fox Solomon: Yes, the close-up. That’s Yaffa. She raised five children alone when her husband left to become “a religious.” She acts in and directs a theater group made up of Israelis, Palestinians, and Africans.

Prose: What’s it like, going through your archive? Looking back.

Fox Solomon: I found frames on contact sheets that I had completely overlooked. I found proof prints that I didn’t particularly value years ago. One is a picture of my mother wearing a dress with cascades of big loops around her neck, which reminds me of her critical eye, how she used to dis anyone who did not meet her standards. She’d say, “You can always tell a woman’s age by looking at her neck.” The photograph [see page 68] illustrates my mother’s concern about her own neck. It also portrays her as an example of a woman who could say, “Women’s lib will ruin everything.” Before I regarded this as a picture of my mother; now I see it as an image of a woman of a certain era who happens to have been my mother.

Prose: Do you think that there are things you can do now that you couldn’t do when you were younger?

Fox Solomon: Probably. I do think there’s some advantage in being older. For one thing, I think I can be more open. I mean, I was always honest with myself and in my work, but I have nothing to hide at this point in my life. Also at this stage I have some other interests that I want to pursue.

Prose: Such as?

Fox Solomon: I am taking voice lessons. And I am taking dance workshops in Canada. I think about writing and telling my stories and I am working on a multimedia installation.

Prose: Can you talk about your book of photos of Poland (Polish Shadow, 2006)?

Fox Solomon: I went to Poland in 1988 and photographed symbolic landscapes and signs. I photographed cemeteries, an apple orchard after Chernobyl, a little girls’ dance class, and I made portraits. In general, the printing was dark. I felt darkness there in 1988. I photographed outside Majdanek camp and I visited Treblinka. When I went back to Poland in 2003, I returned to a different Poland, a Poland that had become part of the Western world. I visited Auschwitz, photographed in a mental hospital, made portraits of mothers and sons. I am Jewish, and though I had photographed in Catholic and Buddhist cultures, I had never addressed the Holocaust. I first went to Poland as a response to the acceleration of ethnic violence throughout the world.

Prose: The Holocaust so permeates that book, but the book never says anything about it really.

Fox Solomon: That’s interesting. I was aware of it the whole time.

Prose: Is there anything else you’d like the readers of Aperture to know?

Fox Solomon: Would it be strange to talk about my prints?

Prose: No, not at all.

Fox Solomon: I just want to say that my printing has been very important to me over the years. That taking the pictures is just one part of the process, and producing the pictures involves a great deal. Interpretive printing is really important.

All photographs courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York

Prose: Here’s an impossible question. How do you know when you get it right with a print? When you get what you’re looking for?

Fox Solomon: It just—I feel it. Even now I supervise somebody who works for me with digital printing. I don’t do it hands-on, but I sit there, and I know that the picture has to be a tiny bit lighter, or needs more contrast. And when it’s right, I just feel that it’s right. It’s an intuitive feeling. It might not be right for somebody else, but it’s expressing what I want to express. It has always been an important part of my work as a photographer.

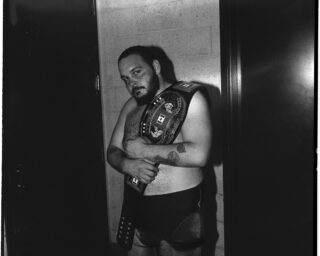

I’ve been talking about printing, but there’s something else. When I photograph an individual, I want to connect with her or his interior. I’m not looking for the outer coating. I want a few moments when we stare into one another, exchanging our histories and feelings in a glance. Something in the way that a person looks at me is part of it, and I capture that. I want intensity. What I can project of myself—and what bounces back from the person I am facing—makes the picture. Sometimes it’s just a moment, a moment of connection.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” Fall 2015.