The Woman Behind the First Photography Gallery

Helen Gee risked everything to open Limelight in 1954, selling prints by Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, and Robert Frank for less than fifty dollars each. Her tell-all memoir, Helen Gee: Limelight, a Greenwich Village Photography Gallery and Coffeehouse in the Fifties, is now available from Aperture as an e-book. Here, Denise Bethel’s introduction offers a preview of the late Gee’s story.

Courtesy Gary Schneider

Dear Helen,

I am writing to let you know that, sixty years on, some of the questions are still the same: who succeeds as a photographer? And, whose photographs sell? When you opened your first show at Limelight, in 1954, you linked those questions together for a new generation of collectors, and they’ve been linked that way ever since. Galleries had been selling art for centuries, but you wanted your gallery to be only about photography. This was an act of courage and an act of faith. Stieglitz sold photographs, and Julien Levy too, but they both offered other art as well. Now, look at what’s happened. In 2014, when I auctioned a sale of photographs for over twenty-one million, I wished you’d been there to see it. I was wearing some of your jewelry that night, given to me by two of your closest friends. There were prints in that auction that sold for tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars, many by some of the same photographers you’d struggled to sell for twenty or thirty or forty dollars a pop—Ansel Adams, Minor White, László Moholy-Nagy, Atget, Berenice Abbott, Gene Smith, Imogen Cunningham, Robert Frank, and more. The list is long. It’s ironic that one of your closing shows, the work of Edward Weston, saw some decent sales at seventy-five dollars a print. It’s all very different now. In my life as an auctioneer, I was as ambitious for the medium as you were, and finally, after years in the low-price trenches, I sold not one, but three photographs by Edward Weston for over one million dollars each.

In those long-ago days of the 1950s, you got into selling photographs through the back door: you were a painter who got hooked on photography, and you became a photographer yourself. You made money retouching photographs, enough money even to hire a secretary. And then you wanted to open a gallery. This was a time-honored route to becoming a dealer—through love of a subject—and in retrospect, it may have been the best one. You couldn’t help yourself, it was almost that simple. This was before photographs had much status in the marketplace, and before they could promise any return on the dollar. In 1980, when I got my first job in the photo trade, we called it “photographica.” Now, it’s “fine art photography,” and it’s a medium that’s sexy, a medium that’s hot, and that element of passion is not the determining factor it once was. Maybe that’s a shame. In 1954, you opened Limelight because you loved it, and you hoped that it would somehow, someway translate into money for food and rent.

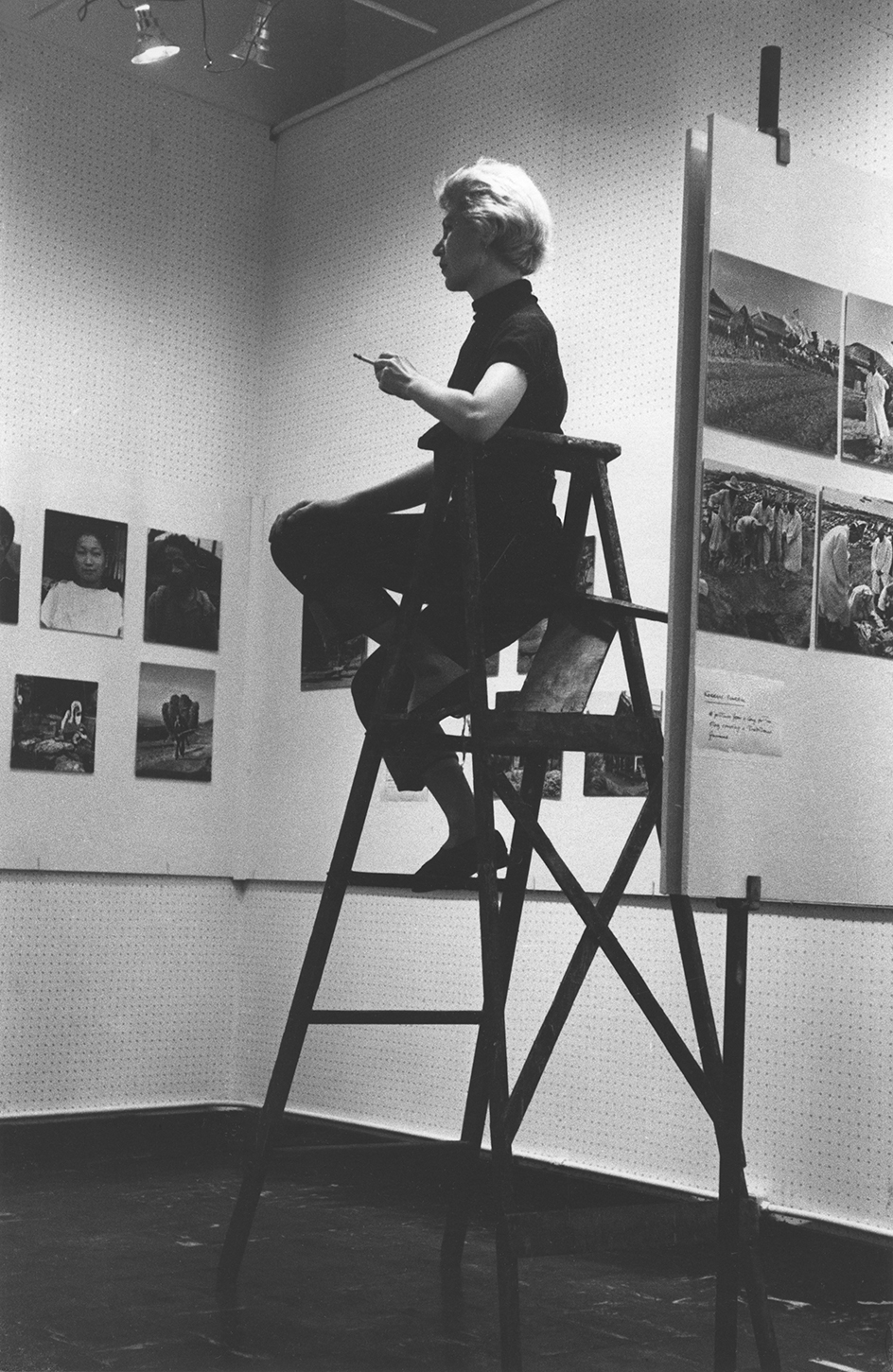

Courtesy Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

For anyone who loves photographs the way I do, your book is a fabulous roller-coaster ride. I love all that gossip and all that juice. People known to me only through their pictures are described by you in wacky detail. Your first photography teachers were Lisette Model and Sid Grossman—Sid kept your classes going on and on past midnight, endlessly pontificating on everything from politics to photo magazines. There were Robert and Mary Frank in their chaotic loft on Twenty-Third Street, boxes everywhere, hard to tell if they were moving in or moving out. The rugged Brett Weston, driving into Manhattan with a gun on his front seat. The tipsy Gene Smith, going from tavern to tavern in the wee hours, threatening to kill himself before he hung his show. The practical Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, glad to clear her husband’s clutter from her closets. Imogen Cunningham holding court at Limelight, giving Peter Hujar one perfect piece of advice. You even babysat the young Robert De Niro, an impossible-to-control toddler with no hint of famous actor in his future. Best of all is your scene with Edward Steichen in a kimono, chasing you around his apartment, putting the moves on. Let’s face it, Helen, you were a looker. But where did you find the guts to turn down Steichen, the most important person in the photography world at the time?

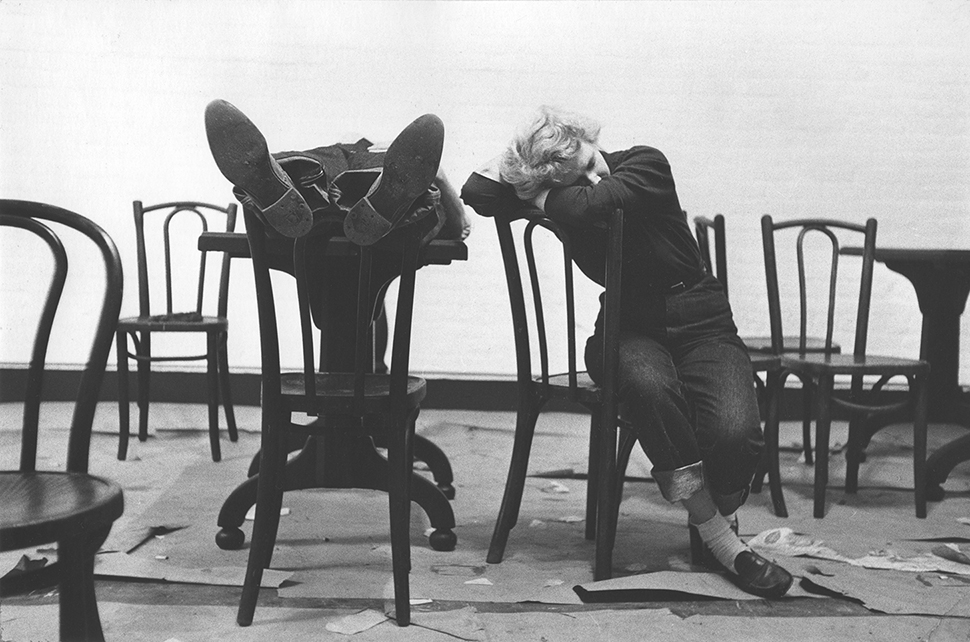

Courtesy Gary Schneider

These stories make your book a page-turner, and it would be a terrific musical: young woman finds a derelict nightclub in Greenwich Village, goes up to her neck in debt, strong-arms friends to help her plaster and paint, opens a coffeehouse–gallery, and the rest is history. Think of what a director could do with this scenario, Helen, think of the songs, the backdrops, the potential dance numbers—photographers in a cancan! Rain coming in through the broken skylights! We can look back and smile at some of this, but not at the tough parts, no—no, thank you. Let’s save the tough parts for the screenplay: the lawyer who cheated you, leaving you stranded . . . the times you faced bankruptcy . . . the crash course in the restaurant business, the endless staff turnover, the bookies in your apartment building, the union organizers who helped do you in. You wanted to figure out how to sell photographs, not how to work coffee machines. But it was food that kept Limelight going when the photographs didn’t sell, and so you had no choice—you figured it all out. That abandoned nightclub before you transformed it into Limelight—good grief. What exactly were you thinking? You recount it all with equanimity and sometimes, against all odds, with humor: the highs and the lows, the triumphs and the failures. And there’s not an ounce of self-pity in the narrative. It’s a lesson for all of us.

Courtesy Gary Schneider

When you did sell a photograph, and it didn’t happen often enough at first, you tell us candidly that it was nothing less than “an event.” You hung sixty shows in seven years, gave a lot of photographers their first exhibition, and created a special space, unique in the city then, for photography people to gather. For better or for worse, you brought photography back into the art market debate. Your shows were reviewed, with gravitas, in the New York Times and the Village Voice. One reviewer in the Sunday Times had the nerve to suggest that, for the modern world, photographs might just be more important than paintings. Whaaaaaat?! And so the controversy started up again, years after Stieglitz had thrown in the towel, and I’m writing to tell you that it’s going on still, today. I remember an Old Masters collector who walked into a photo auction preview by mistake. He was stunned when he saw the estimates. “Why, you can buy a good painting for what some of these things are worth!” he said to me, outraged. You just have to keep smiling, right?

Courtesy Gary Schneider

If you had just been able to hang on for a few more years, Helen, just a few. If you had just been able to figure a way around the union who tried to recruit your ragtag staff of part-time actors and out-of-work dancers. You were living one week to the next as it was, on borrowed time. Who could have predicted what the last straw would be, after all the creditors you’d dodged and all the photographers you’d cajoled? It’s heart-breaking to me that you closed when you did, because photography was about to move into the art world in a big, big way. Lisette Model introduced you to the young Diane Arbus, right at the end of your run. Grace Mayer brought by a Midwesterner named John Szarkowski—he was in town for a job interview at the Museum of Modern Art. Less than a decade after Limelight folded, Lee Witkin started down the trail you’d blazed: he opened his gallery in Manhattan, in 1969, and others followed. New York and London began to auction photographs in the 1970s, and slowly the prices went up. In 1989, I was in the room when a photograph broke that magic one-hundred-thousand-dollar ceiling at auction—an Edward Weston nautilus shell. Applause broke out, and all of us thought we’d hit the big time. Yet prices kept on going. In 2006, I was at the podium for the first photograph, classic or contemporary, to sell at auction for over a million dollars, $2.93 million, in fact. It was The Pond—Moonlight, a Pictorial tour de force by your old friend Edward Steichen. And again, I was wearing some of your jewelry that night, wishing you could be in the room to see it. What would you have thought if you had seen that $2.93 million in the press, who by then was jumping on every meteoric rise in price for photographs?

Courtesy Gary Schneider

Does reading your book now, when so much has changed, make me miss those historic old times? It’s romantic to read about, Helen, but maybe not to have lived it. You had the strength of an ox. Now there are more of us in the business, and there is safety in those numbers. You were thrilled when Roy and Anne DeCarava opened a gallery in their apartment on the Upper West Side, because you knew it would be good for Limelight as well. It closed before you did, unfortunately. You tried new kinds of food to keep the doors open and reviewed endless portfolios for free, but it was always a cliff-hanger. In the 1950s, selling photographs was not the way to get rich, that’s for sure. You were far, far out on a limb.

Courtesy Gary Schneider

And, yes, there’s one more question your book brings up, and it’s a question, like the others, that’s still with us today: not who succeeds at selling photographs, but can it be a woman? Being a woman, Helen, might not have been the easiest way to start. When I climbed into the auctioneer’s box for the first time, I was the first female auction head of photographs to actually take a sale. (“You need to stand up in the podium, don’t sit down up there,” a friend recommended later, when he saw how the box engulfed me. “I am standing up,” I had to tell him. “I’ve been standing up for years.”) Although there are many—many—more women in the photo world today, we’re still outnumbered. And, to top it all off, in your Limelight years, you were not just a woman, you were a divorced single mom. You stayed up nights working, retouching photos, you worked when you were sick, you scrambled to find babysitters, you read all those books on raising children, you wanted your daughter to have the best. Thank you for being frank with us about trying to find the time to date and to make those tricky man-woman relationships work. How did you have any stamina left at all? For single moms out there, career moms with not much money, like you, I expect this may not have really changed.

Courtesy Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

Helen, I’m such a fan. We don’t have enough in print about what it was like in the early days of the photo trade, and in your case, a memoir about the business has become a memoir about the medium itself. Although I adore all that gossip, my favorite parts of the book are your zingers about the lasting (or not!) value of the photographs and exhibitions of your day—your pages on The Family of Man, for starters. Your right-on comments about the whole photo scene can’t be paraphrased—and so I’ll leave it to new readers to discover for themselves your razor-sharp eye. You would have been a great critic, Helen, because you knew the medium from the inside, and you made it your business to know the people. I am in awe of what you did, and for taking the time and trouble to put it down on paper.

With all best wishes,

Denise Bethel, New York, January 2018

Denise Bethel, formerly Chairman, Photographs, Americas, Sotheby’s New York, is now an independent advisor, a writer, and a lecturer based in New York City.

This essay was originally published in Helen Gee: Limelight, a Greenwich Village Photography Gallery and Coffeehouse in the Fifties.